this ain’t your grandpappy’s Atlanta

I spent the first Sunday morning in our new Atlanta home heaving worldly possessions from our PODS (Portable On Demand Storage, highly recommended) container to the garage in 95-degree heat. At 10 o’clock I caught the eye of a neighbor mowing his lawn. He nodded and smiled. I nodded and smiled. Not in church, eh? we said telepathically. That’s right, we each responded. Two sweaty joggers bobbed by, presumably not church-bound.

Nod.

Nod.

Standing in line at the post office last week, I counted accents. I heard 28 people speak long enough to take a reasonable guess. Several distinct New Yorkers (including one behind the counter), a Bostonian, a possible New Jerseyite, at least three Midwesterners, an English woman, an Indian couple, and two women from California. Others were hard to place but definitely un-Southern.

So how many of the 28 had even a trace of a Southern accent? Three.

Our realtor is from Indiana. Our neighbors on the left are from California. Across the street is Michigan, and next to her, upstate New York. The guy who fixed our phone cable is from Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

I’m beginning to see why Southerners call Atlanta the “New York of the South.” It ain’t just the skyscrapers — it’s the New Yorkers. We’re in North Fulton County, an area exploding with newbies from everywhere but here, many brought in by the Fortune 500 companies based in town.

And we’re in an area more diverse than the one we left in Minneapolis. Our immediate neighborhood includes families from Indonesia, Taiwan and Pakistan. The populations at my kids’ schools are 40% non-white.

This is goooood.

It’s not that Northern is better than Southern, non-white better than white, or non-religious better than religious. It’s sameness that’s the enemy. I REALLY don’t want my kids growing up surrounded by people who look and think and act just like they do. As a teenager, I remember barfing inwardly at the phrase “Celebrate Diversity!” — until I spent some time surrounded by conforming sameness and watched all of the grotesque pathologies that bubble out of that. I’m a white liberal nonbeliever, but I know better than to want my kids growing up in an area that’s all-white (been there), all-liberal (done that), or all non-believer (don’t even wish for it). I want a mix.

And here in the northern stretch of Atlanta, as a result of the infusion of difference in the past 20 years, my kids are going to grow up in a much more diverse and cosmopolitan place than I sometimes feared in the weeks leading up to the move, laying awake in a cold sweat, staring at a ceiling that kept turning into the Stars and Bars and imagining the new neighbors as some combination of this

…and this

Though these guys are surely around, they’re a helluva lot rarer than the worst of my sleepless Minnesota nights would have had me believe. Isn’t that usually the case? Don’t I usually find that late nights are the worst time to measure reality? So when will I finally learn to tell my insomniac fears, once and for all, to bugger off?

By clicking on the lights one at a time, I guess. All that to say: now that I’ve seen Atlanta with the lights on, I like it.

love and law

Jiminy Christmas! What were you thinking, letting me ramble on like that in the last post! 2100 words! Speak up when I do that!

But somewhere in among the concordances and Schenker graphs and my Aunt Diane’s potato salad recipe back there, I made a promise to look at the concordance for another kind of Christian parenting book, so here’s a coda.

Compare the concordances for (shudder) John MacArthur’s What the Bible Says About Parenting and another Christian parenting book called Parenting With Love and Laughter: Finding God in Family Life, or PLL, by Jeffrey Jones:

You may remember that a particular cluster of frequent words in What the Bible Says About Parenting set my teeth on edge last time — OBEDIENCE, OBEY, SIN, DUTY, EVIL, FEAR, AUTHORITY, DISCIPLINE, COMMAND, COMMANDMENT, SUBMIT, LAW, INSTRUCTION, etc. But of those 13 words, not a single one appears in the top 100 of the Christian parenting book by Jeffrey Jones.

On the contrary, the Jones book seems to favor more humane, loving language and ideas. The word choices in What the Bible Says About Parenting indicate a view of childhood as a period of numb, acquiescent discipleship. You’d think these two were coming at the world from very different points of view — and you’d be right.

You might even be tempted to say the concordance of PLL has more in common with Parenting Beyond Belief than either does with the other. You’d be right there, too. Of the top 50 words in Parenting with Love and Laughter, precisely half are also in the top 50 of Parenting Beyond Belief. But PBB shares only one quarter of its top 50 words with What the Bible Says. Coincidence? I think not. Common words, to a point, reflect shared ideas. MacArthur would surely be as thrilled as I am to be placed solidly in separate camps.

So how can two Christian parenting books differ so dramatically in their essences–at least so far as the concordances reveal?

Of Love and Law

I’ll let Bruce Bawer handle this one.

Author/commentator Bawer (Stealing Jesus: How Fundamentalism Betrays Christianity) wrote a piece in the New York Times ten years ago while the Presbyterians were tearing themselves apart over the ordination of gays — just like the Episcopalians have done more recently. It was a sharp and illuminating piece that instantly snapped the American religious landscape into perspective for me. Here’s a taste:

American Protestantism…is being split into two nearly antithetical religions, both calling themselves Christianity. These two religions — the Church of Law, based in the South, and the Church of Love, based in the North — differ on almost every big theological point.

The battle within Presbyterianism over gay ordinations is simply one more conflict over the most fundamental question of all: What is Christianity?

The differences between the Church of Law and the Church of Love are so monumental that any rapprochement seems, at present, unimaginable. Indeed, it seems likely that if one side does not decisively triumph, the next generation will see a realignment in which historical denominations give way to new institutions that more truly reflect the split in American Protestantism. — THE NEW YORK TIMES, 5 April 1997

Though Bawer is talking about Protestants, the same fault line runs down the middle of American Catholicism, between venomous literalists and social justice-loving practitioners of genuine agape–unconditional love. And I don’t think it’s hard to see which of the above books is in which camp.

Christians I know are too quick to dismiss the “church of law” as an aberration, something unfortunate but…you know… over there somewhere. And atheists are often just as quick to overlook the presence of the “church of love.” My major complaint with that side of American Christendom isn’t that they have supernatural beliefs. As long as they do good with them, who cares? My complaint is that the church of love does far too little to confront its ugly fundamentalist stepsister. Worse yet, it arms her by indiscriminately promoting faith as a value in and of itself.

ANYway

I think Bawer’s model is revealing, and I think the concordances back it up nicely — one from the church of love, the other from the church of law. Two very different brands of Christian parenting are in play there — one with which I can surely find plenty of common ground, and the other…well, not so much.

The central point of PBB, as noted in the Preface, is to demonstrate for parents “the many ways in which the undeniable benefits of religion can be had without the detriments.” There are some things to emulate, adopt, and adapt from religious parenting into the religion-free model — and the place to look is in the church of love, not law.

(785 words. That’s the ticket.)

The distiller’s art

Distillation’s been on my mind lately — the art of condensing something ungraspably large into a graspable essence. I mentioned Carl Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar a few weeks ago, a distillation of universal history that instantly focused my understanding of just how recent we are — and how small we are, and how deep and silly our delusions of bigness are.

Distilling space

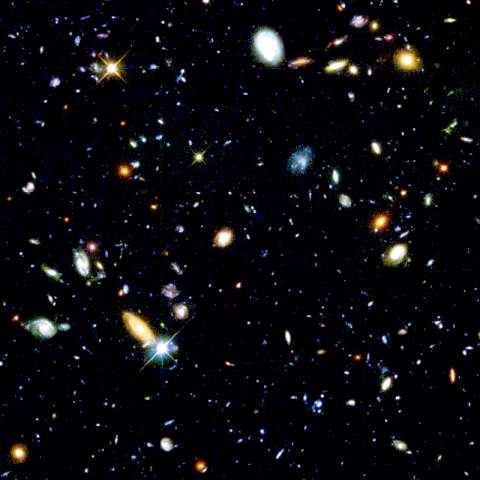

Here’s another distillation of a sort:

This image, called the Hubble Deep Field, must be the greatest picture of all time, a deep space image by the Hubble Telescope. How much sky does this represent? Imagine a dime held 75 feet away. The portion of the sky that dime would cover is the portion represented here. And it’s a patch of sky that appears essentially empty when viewed by ordinary telescopes. Most of the dots of light are not stars but galaxies. And this is one infinitesimal dot of space.

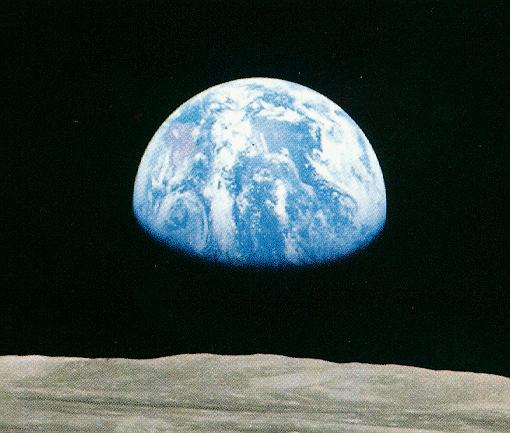

The Hubble Deep Field is my laptop background, and I sometimes find myself staring at it for ten minutes at a whack. It rivals Voyager’s famous “pale blue dot” photo and the first glimpse of Earthrise from the Moon for the granting of instant and lasting perspective for those who are awake:

You are here: The tiny dot is Earth viewed from Voyager II.

The 1968 paradigm rattler.

I love the particular headrush you get from this kind of distilled reality, the epiphany (sorry, it’s the best word) that can be achieved by snapshots capturing essences otherwise too large to grasp. In a single glance, I GET it.

Distilling time

Here’s another one:

That won’t mean anything to you normals, but having spent 25 years studying or teaching music theory, it’s something that makes me swoon. Music is notoriously tricky to get your hands on. Visual art is form and color arrayed across space, so you can snap on the rubber glove and it’ll hold still for the examination. Music, by contrast, is sound arrayed across time. Time is its body, so you can’t get it to hold still without killing it.

“If you try and take a cat apart to see how it works,” said Douglas Adams, “the first thing you have on your hands is a non-working cat.”

An Austrian music theorist named Heinrich Schenker developed a method for reducing a complex and ever-moving piece of music into a graspable snapshot. The chart above is a Beethoven string quartet movement of nearly 400 measures reduced to its essence. Foreground, middleground, and background, harmony and melody, it’s all there.

And–it’s not all there. Schenker didn’t intend this to replace music, but to give a little window of understanding, another way to GET it. I love to listen to Beethoven quartets, and I love to understand them as well. Then listening while understanding — don’t get me started.

Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar, mentioned above, is another time distiller, of course.

Distilling thoughts

Books are another tough nut to crack. By the time you get to the end of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, or The God Delusion, or Left Behind #13 — Kingdom Come, the sense of what a given book was “about” can reasonably vary from person to person. A friend reads Dawkins and hears a constant stream of invective. I read Dawkins and hear a constant stream of reasoned argument. No point saying one of us is definitively right or wrong. But there is one kind of snapshot distillation that I think sheds some interesting light — the concordance.

One type of concordance is a list of all the words appearing in a given book. Not the same as an index, which is a list of all concepts, whether or not they appear verbatim in the book. Somewhat subjective, the index. A concordance simply counts and reports. The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, for example, includes a long concordance that is misnamed “Index.” In it, you can find the apparent only significant use of the word “maggot-pie” — by Shakespeare, who else — and learn that the great quotesmiths have preferred to go on about love (586 times) more than hate (72 times). That’s nice.

But there’s another kind of concordance, one that can grant a bit of that snapshot distillation I’m on about. This kind records the most frequent words in a book.

If you hate “reductionism” — I myself happen to have a lifelong schoolboy crush on it, dotting its ‘i’s with little hearts as I write its name a thousand times on my three-ring binder — but if you hate it, you’ll hate concordances. They don’t reveal everything about a book, of course. If a concordance says the word MEAN appears 632 times in a book, does that indicate an obsession with hostility, or with significance, or with mathematical averages? And even if it is about hostility, is the book fer it or agin it? Maybe “mean” is always preceded by the phrase please don’t be.

The Hubble photo doesn’t tell us everything about the universe, either. It just gives us an insight, a new way of seeing it. Same with the concordance.

(Okay, the casual readers have long since gone. As a reward for the rest of you, here comes the point.)

I don’t know whether you’ve noticed, but for the past several months, Amazon.com has been sprouting new features like a house afire. My favorite new feature is, of course, the concordance. The 100 most common words in a given book are arrayed in a 10×10 block with font sizes varying by frequency. Huge-fonted words appear a lot, medium-fonted words etc. You get a fairly powerful sense of content, approach, and tone at a glance. I daresay I could show you concordances for books by Benedict XVI and Lenny Bruce and you’d know which was which — and which you’d rather read. (No no, don’t tell me, I’m keen to guess.)

Here, for example, is a concordance for one of my favorite recent books. Just looking at those hundred words makes me want to read it a fourth time.

The Point

Below are concordances for two parenting books, with the 100 most common words in order of frequency (in batches of ten for easier reading). One is about raising kids using biblical principles; the other is about raising kids without religion. See if you can tell which is which, and whether the concordances reveal anything about content, approach, and tone:

BOOK A

1-10: children—parents—god—child—love—own—husband—family—lord—word

11-20: wife—teach—heart—sin—christ—father—need—life—things—even

21-30: kids—should—man—must—son—proverbs—parenting—mother—does—scripture

31-40: kind—wisdom—evil—first—church—shall—may—home—fear—authority

41-50: marriage—obey—christian—ephesians—law—work—right—come—principle—means

51-60: take—truth—wives—woman—time—true—good—himself—solomon—give

61-70: live—men—let—paul—role—society—duty—honor—commandment

71-80: obedience—responsibility—teaching—against—gospel—know—therefore—verse—discipline—people

81-90: submit—something—themselves—jesus—want—women—wrong—world—day—think

91-100: instruction—faith—always—attitude—command—ing—certainly—spiritual—genesis—now

BOOK B

1-10: children—god—parents—religious—time—people—child—good—things—life

11-20: family—religion—world—think—believe—secular—know—even—beliefs—may

21-30: years—questions—own—right—kids—human—death—reason—first—school

31-40: idea—need—day—should—ing—moral—see—live—want—new

41-50: book—help—now—find—say—take—work—answer—others—something

51-60: church—come—wonder—bob—values—age—friends—get—go—little

61-70: does—without—long—often—true—thinking—feel—stories—must—love

71-80: exist—part—give—important—really—animals—two—great—kind—might

81-90: humanist—best—look—seems—still—atheist—few—thought—mean—mind

91-100:kobir—different—though—meaning—experience—problem—always—fact—adults—ceremony

Book A is

Book B is

The first observation is among the most interesting: that these two books, though different in many, many ways, have the same top three words. Even more interesting is that the secular parenting book mentions God more often. Not entirely surprising if you think about it. The top four words in Quitting Smoking for Dummies are SMOKING, SMOKE, TOBACCO, and CIGARETTES.

Next we notice a few surprises, like the fact that the concordance program promotes the suffix ‘ing’ to the status of a word, and that a dialogue in my book ends us up with the speakers’ names — Bob and Kobir — at #54 and #91, respectively.

Right, right…the point

One of the first things I noticed in comparing the two is the relative importance of obedience. What the Bible Says About Parenting uses the word OBEY 66 times and OBEDIENCE 49 times, while the same words appear only six and four times (respectively) in Parenting Beyond Belief — even though PBB is almost exactly twice as long. As a percentage of text, these words appear twenty-two times more frequently in the religious parenting book than in the non-religious one. I find that revealing, though not exactly surprising. I want my kids to know how to obey, sure, but it’s sixth or seventh on the list of my hopes for them (as I’ve written elsewhere). Seems a tad higher on the list for What the Bible.

What about parenting books in-between? I looked at two current mainstream bestsellers, Parenting From the Inside Out and I Was a Really Good Mom Before I Had Kids — neither of which includes OBEY or OBEDIENCE in its concordance. Religion and obedience seem particular stablemates.

I’m dismayed, but again unsurprised, that love is #5 in WTB and #69 in PBB. To tell the truth, I’m relieved it’s in our top 100 at all. Freethinkers love no less, of course, but we spend most of our time talking about truth and generally let love take care of itself. Religious folks often do the opposite, talking of endless love and letting truth tag along if it can keep up. And lo and behold, THINK is #14 for us and #89 for them. Also high in our list are the lovely words QUESTIONS (#22) and IDEA (#31) — neither of which appears in the other list.

The presence of words like HUSBAND, WIFE, SON, MOTHER, and FATHER high in the WTB list might indicate that role divisions are important. None of these appear in the PBB hit parade, which I think indicates less emphasis on divided roles. Perhaps I’m reading too much into these things. (READER: No no, I think you’re onto something!)

The presence of EPHESIANS on the WTB list makes some sense, since the end of Ephesians lists several familial duties — ‘Wives, submit to your husbands as to the Lord,’ (5:22) ‘Husbands, love your wives’ (5:25). But the fact that EPHESIANS appears 64 times just baffled me — until I remembered one of the most chilling verses in the NT:

Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. Honor your father and mother — which is the first commandment with a promise — that it may go well with you and that you may enjoy long life on the earth (Eph 6:1-3).

The conditional phrase “that you may enjoy long life” is no metaphor: It refers directly to Deuteronomy 21:18-21:

If a man have a stubborn and rebellious son, which will not obey the voice of his father, or the voice of his mother, and that, when they have chastened him, will not hearken unto them; Then shall his father and his mother lay hold on him, and bring him out unto the elders of his city…and they shall say unto the elders of his city, This our son is stubborn and rebellious, he will not obey our voice…And all the men of his city shall stone him with stones, that he die.

(For those who insist the OT is no longer in force, that it was replaced by a “new covenant” in the NT, Jesus wants a word with you. Now.)

Neither Ephesians nor Deuteronomy appears in the PBB top 100. Phew. We write about how to talk to kids about death (#27), but these guys threaten them with it. Okay okay, not directly…but by quoting the hell out of Ephesians, some (not all) religious folks show their enthusiasm for ultimate punishments in no uncertain terms.

I could go on and on, pointing out the high frequency of words like SIN, DUTY, EVIL, FEAR, AUTHORITY, DISCIPLINE, COMMAND, COMMANDMENT, SUBMIT, LAW, and INSTRUCTION in WTB, and the absence of any of those in PBB’s top 100, and the wholly different brands of parenting implicit in such observations. I could. But it seems equally important to point out that not all religious parenting books share the numbingly authoritarian quality that the concordance of What the Bible Says About Parenting seems to bespeak. In fact, I’d like to show you another Christian parenting book that has almost NONE of the sad and disheartening earmarks of WTB, James Dobson, and the rest of that ilk. But I’m sleepy. Next time, then.

(Here’s the link to PBB’s Amazon concordance, btw.)

mythed it by that much

I’m working on a pretty complicated entry for later this week — you’ll see what I mean — so here’s a quickie to fill the gap.

My daughters (5 and 9) are currently eating up Greek myths as bedtime stories. Friday was Dedalus and Icarus, yesterday Pegasus and Bellerophon. Tonight I told the story of Danaë and Perseus, completely forgetting that I’d used it as an example in PBB. “Buy a good volume of classical myths for kids,” I suggested on p. 37, “and buy a volume of bible stories for kids.”

I’ll sheepishly admit here that I don’t quite follow my own advice. I find that published bible stories do an incredible disservice to the tales they tell. They are either crushingly dull or sickly sweet or both, so my kids’ exposure to Judeo-Christian stories has come from (1) their Lutheran preschooling, (2) Jesus Christ Superstar, which I highly recommend as a naturalistic intro to the Jesus story (see PBB p. 70 for reasons), (3) conversations with their Episcopo-Baptistic granny, with their undeclared mom, and with atheo-secular-humanistic me.

I went on in PBB to say:

Begin interweaving Christian and Jewish mythologies, matched if you can with their classical parallels. Read the story of Danaë and Perseus, in which a god impregnates a woman, who gives birth to a great hero, then read the divine insemination of Mary and birth of Christ story. Read the story of the infant boy who is abandoned in the wilderness to spare him from death, only to be found by a servant of the king who brings him to the palace to be raised as the king’s child. It’s the story of Moses – and the story of Oedipus. No denigration of the Jewish or Christian stories is necessary; kids will simply see that myth is myth.

Turns out in the case of my nine-year-old that I didn’t have to be anywhere near that intentional.

So again, tonight was Danaë and Perseus. Danaë is the daughter of King Acrisius. The king hears from an oracle that Danaë will bear a son who will grow up to kill him. Unable to bring himself to kill his daughter outright (isn’t that sweet?), Acrisius instead imprisons her in an underground house of bronze with only a small opening to the sky. One night, a golden rain comes swirling in through this opening and around the chamber. A short time later, it is revealed to Danaë in a vision that she is carrying the child of the god Zeus.

“WAIT A MINUTE!” said Erin, leaning forward in bed, eyes wide. “Oh my gosh! There’s another story like this!!”

I smiled and waited patiently as she thumped her forehead, trying to remember. At last, she blurted out:

“Life of Brian?”

choosing your battles

I’m all Southern now. For proof, see last post, in which God and football are mentioned in the same breath.

Somebody emailed me to ask why exactly I’m not girding for battle over the inclusion of God as one of the four team values for my son’s public football league. Let’s suppose for a moment it was a serious question. When it comes to religious incursions into public life, how do you decide when to fight and when to let it be?

Since I edited Parenting Beyond Belief, I’ve heard stories of church-state violations that would make your fries curl: public school marquees with Bible verses, a public kindergarten teacher showing the bible-based Veggie Tales and reading from In God We Trust — Stories of Faith in American History, even a values assessment in a public high school that gave kids a lower values score if they didn’t attend church or believe in a “higher power.”

Like the aforementioned curly fries, some of these are small issues, some are medium — and some are SuperSize. To sort them out, it’s a good idea to think about why church-state separation exists. It does not exist to “avoid offending atheists.” Ed Buckner put it this way in Parenting Beyond Belief:

Many people do oppose separation of religion and public education, of course, but most do so because they lack good understanding of the principle and its purpose. The most common misunderstanding is that separation is designed to protect religious minorities, especially atheists, from being offended. Offending people without good reason isn’t ever a good idea, but that isn’t the point of separation. Separation is necessary to protect everyone’s religious liberty.

THAT is what separation is for. If I tell you I’m in favor of putting God back in schools, half of my relatives would cheer — until I announce that it’s Chac-Xib-Chac, the Mayan god of blood sacrifice, who will be worshipped, and the Mayan creation story that’ll be taught as true.

THAT is what separation is for. If I tell you I’m in favor of putting God back in schools, half of my relatives would cheer — until I announce that it’s Chac-Xib-Chac, the Mayan god of blood sacrifice, who will be worshipped, and the Mayan creation story that’ll be taught as true.

Suddenly I’m no fun at all.

Likewise, if I said our prayers would be specifically Catholic — that we would pray to Mother Mary and invoke the name of Benedict XVI each morning, for example — there’d be Protestants laying bricks in the principal’s office.

Nobody understood this better than Southern Baptists at their founding. They were a tiny minority then, you see, and didn’t want some majority vision of God forced on their kids. Here’s Dr. Ed again:

The Southern Baptist Conference understood the point so well that it included separation of church and state as one of its founding principles. The Southern Baptists adopted, in their “Baptist Faith and Message,” these words: “The church should not resort to the civil power to carry on its work….The state has no right to impose penalties for religious opinions of any kind. The state has no right to impose taxes for the support of any form of religion.” Only by consistently denying agents of government, including public school teachers, the right to make decisions about religion is our religious liberty secure.

But now that they’ve made it into the mainstream, why, they can’t quite remember what all the separationist fuss was about.

If I heard that a teacher at my kids’ school was advocating atheism — saying specifically that God does not exist, for example, and telling the kids they should believe the same — I’d be the very first parent demanding his or her head. Secular schools are not the same as “atheistic” schools. They are neutral on religious questions — and that, you careful readers of the Constitution will know, is the American Way.

Anyway, back to my boy’s football thing. Stu Tanquist (whose essay title I stole for this entry) offered a list of considerations in Parenting Beyond Belief:

When considering whether or not to challenge religious intrusion in our lives, there are many factors to consider:

• Is your child concerned about the consequences?

• Could your child be negatively impacted by the challenge? Might he or she be ostracized at school by teachers or students?

• If successful, how significant would the change be? Would it positively benefit other families and children?

• Could you and your family be negatively impacted?

• What are your chances of success?

• How much time and resources are required?

• Do you risk damaging existing relationships?

• Is this likely to be a short-term or long-term fix?

• Is legal action necessary?

• Are there other parents or organizations that could assist you?

• Are you bored? Do you really need the spice this will add to your life?

• Would it feel rewarding both to you and your child if you succeeded?

This list isn’t designed to spit out the “right” answer; it simply raises the right issues. “Damage to existing relationships” is unfortunate, but in some cases might be outweighed by “positive benefit [to] other families and children.” Read his chapter and you’ll see how Stu geared his own responses, sitch by sitch, as his daughter encountered religious incursions in her public education.

The most important point Stu makes is the importance of considering the child’s wishes. Pushing a point your child doesn’t want pushed might do far more damage to your parent-child relationship than the issue is worth.

In the end, the football thing was a no-brainer. Compared to the likely consequences — especially for the new kid — it just doesn’t matter enough. God is just being presented as a value — inappropriately so, yes, but the effect is mild. My boy isn’t being forced to pledge individual belief in God, as he was (repeatedly) in Scouts. And he’s less impressionable now, better able to think for himself, so I’m not concerned about him being unduly influenced by an admired figure like his coach.

There are certainly cases in which I would stand up — and have. This just isn’t one of them. I’d be interested to hear what you think about Stu’s list — if there’s anything you’d add or subtract, for example — and whether you’ve come up against separation issues and how you handled them.

PBB Top Ten for July

- July 31, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In Atlanta, PBB

9

9

10. Newsweek story puts PBB in the spotlight

It ends in a glowing endorsement, but first there’s some wading to do. The column starts by declaring both parenting and atheist books “useless and irresistible,” proceeds to a quick but nice synopsis of the book’s content and approach, gives the false impression that there’s an atheist backlash of some sort, then finishes by saying “parents on both sides of the culture war will find this book a compelling read.” All in all a lovely development in the promotional life of the book. (Better than Obama’s fate: appearing on the cover under the (unrelated) banner TERROR’S NEW FACE.)

.

.

9. Amazon rank spikes to #365

Amazon has 3.5 million titles. The average megabookstore carries the top 1% — about 35,000. In the week after the Newsweek story appeared, PBB was in the top 1-2% of that group. I hope you’ll forgive the editor-chimp for banging his chest over these numbers. Remember that I heard for four years that there was no audience for such a book.

.

.

8. PBB confounds conventional book sales pattern

Ignoring titles by such titans as JK Rowling, Toni Morrison, and Pamela Anderson, most books do most of their sales in the first six weeks of publication, then enter a long, slow slide to the bargain table. PBB, on the other hand, premiered at 3000 on Amazon, remained in that range for ten weeks — then shot up into the hundreds. This indicates a long likely life.

.

.

7. Flood of PBB orders breaches levees of largest South American river

The deluge of orders following the Newsweek piece caused a certain online retailer to suspend ordering entirely. My initial feeling that this was a mistake was quickly put to rest when I spontaneously realized it was brilliant and far-seeing. After 11 days, the book was restored to regular status.

.

.

6. Barnes & Noble rank spikes to #185

During the period when a certain other retailer had the book offline, customers found BarnesandNoble.com just fine, sending PBB’s rank to #185 and into the overall Parenting Top Ten.

.

.

5. PBB is everywhere. At last.

Bookstores nationwide had an understandable wait-and-see attitude toward the book’s saleability in the early going. Now most of the major chains appear to be stocking PBB. Check the parenting section of a bookstore near you!

.

.

4. The vanishing play

Strange goings-on this month at THE MEMING OF LIFE. PBB’s editor satirically vented some frustration with a certain online retailer in his blog and was swiftly called on the carpet by unseen forces with whom, he was reminded, his destiny is wonderfully entangled. Since the point of the satire had been to channel frustration into humor, the overserious response threw the editor for a loop, whatever that means. In order to restore his perspective that life is a dish best served silly, he began speaking of himself in the third person, scotched the whole blog entry, and set aside the troubling issues of corporate control of free expression and open critique, issues that now safely fester deep in his psyche. Tick. Tick. Tick.

.

.

3. Speaking engagement at Center for Inquiry, West

Just eight days after arriving in my new hometown of Atlanta, I flew to LA to address the Southern California chapter of Atheists United at CFI West on Hollywood Blvd. Nice folks, good questions, great setting in the Steve Allen Theater.

.

.

2. Editor moves to South, meets God’s people

Two weeks after moving from Minneapolis to Atlanta, the editor reads the Four Motivating Values for his son’s (public) community football league. Value #1: GOD. Editor has fun pretending to wife that he is arming for battle.

.

.

1. Whispers of television

There are whispers — early, unconfirmed whispers between trenchcoated, chain-smoking figures in unlit parking structures — that a well-known left-leaning cable talk show may invite the editor of PBB to be a guest this fall. No, not that one. Not that one either. Yes yes, that’s the one! Now shush.

mirror, mirror, in my head

- July 28, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In morality, My kids, Parenting

18

18

My kids hate getting in trouble. They also hate actual punishment, of course, which is why we keep careful track of the things they love so we can yank them away when the time is right. It’s what parents and all other petty gods do.

But we don’t often get to the punishment, actually, or even to the threat of it. Just knowing Mom and Dad are seriously ticked is often enough to make our kids sit in shock, staring a hole in the carpet.

A few years back, Connor went through a phase when the words “I’m so disappointed in you” could dissolve him in tears.

It was a kind of Golden Age.

Whenever an interviewer asks on Earth how kids can develop a moral compass without the punishment and reward systems of religion, I think of scriptureless Connor begging us to turn off the hot light of human disapproval.

Though I have no favorites among the essays in Parenting Beyond Belief, one of my favorites is “Behaving Yourself: Moral Development in the Secular Family.” In it, Jean Mercer lays out Kohlberg’s six-stage model of moral development. Fear of punishment is the first and lowest stage. If something an infant does is followed by some kind of nasty consequence, it’s bad. If not, it’s good. Soon we add stage two, hope of reward.

Stage three is social approval and disapproval — the one that hits my kids hardest at the moment.

Fourth is the recognition of laws or rules as valuable in themselves. The Ten Commandments crowd is big on this one. Stage five is the social contract level, in which laws or rules are seen as desirable but made by consensus and potentially changeable as the consensus changes. (Religious commentators typically scream “Moral relativism!” at this point and swallow their tongues.)

The sixth and highest level of moral development is reached when a person thinks in terms of universal ethical principles and is occasionally willing to defend such principles at the risk of punishment, disapproval, or even death. Sitting at this particular moral pinnacle are such religious figures as Thomas More, Martin Luther King and Jesus Christ, and such freethinkers as Michael Servetus, Galileo Galilei, and Thomas Paine.

But there’s another model Mercer presents that really goes to the heart of things, an “essential set of skills” called Theory of Mind. Listen to Auntie Jean:

Theory of Mind allows each person to be aware that behind every human face is an individual set of experiences, wishes, beliefs, and thoughts; that each of these sets is in some ways similar to and in other ways different from one’s own set; and that facial expressions and other cues can enable each of us to know something of how others feel and what they are going to do.

The development of Theory of Mind has already begun by nine or ten months, when a well-developed baby can already show the important step of joint attention. In this behavior, the child uses eye contact and movement of the gaze to get an adult to look at some sight that interests the baby and then to look back again, to gaze at each other and smile with mutual pleasure. Importantly, not only can the child do this, but he or she wants to do it, demonstrating the very early motivation to share our happiness with others—surely the foundation of empathic responses. Without this early development, it would hardly be possible to achieve secular values such as a concern with equal rights, a principle based on the understanding that all human beings have similar experiences of pleasure and pain.

But is the “motivation to share our happiness with others” the only foundation of empathy? Turns out not. And here’s where I start to break out in intellectual giddybumps.

Once in a long while, a scientific discovery of unusually sweeping explanatory power comes along. Big Bang theory snapped countless things about the universe into place with a CRACK. Evolutionary theory does likewise. The more thoroughly you understand what evolution is (and isn’t), the more you can see great thundering blocks of reality falling neatly into place. It is astonishingly, gorgeously, mind-blowingly, jaw-droppingly powerful.

(Yeah yeah…if I love it so much, why don’t I marry it. You are so immature.)

Another discovery on the order of the Big Bang and evolution was made not long ago in the area between your ears — in the three-pound dog’s breakfast we all carry around in our heads.

In your head are some neurons that fire whenever you experience something. Pick up a marble, yawn, or slam your shin into a trailer hitch, and these neurons get busy. No news there.

But this just in: These neurons also fire when you see someone else picking up a marble, yawning, or slamming a shin. They are called mirror neurons, and they have the powerful capacity to make you feel, quite directly, what somebody else is feeling. Here they are, in green:

Whoa, whoa. Wait for it, now. But you do see where we’re going with this. The implications are gi-normous, since it means we’re not completely self-contained after all. No man is an island, and all that. We’re plenty vulnerable to the experiences and feelings of others. Mirror neurons are the reason that yawns are contagious. They are the reason we wince when we see a car door slam on somebody else’s fingers.

But first things first. Why did we evolve mirror neurons? Whenever my kids ask an evolutionary ‘why’ question, I ask them to think about what the absence of the feature would have meant.

Mirror neurons make teaching and learning much easier, for one. All primates have them, so it turns out monkey see, monkey do is a matter of hardware, not just software.

When Cave-Kid saw Mom or Dad starting a fire, or picking berries, or spearing dinner on the hoof, mirror neurons would have made it much easier to duplicate the task him/herself. Populations without this cool adaptive anomaly would have had a selective disadvantage, resulting in fewer survivors over time, and voilà! Mirror neurons become the norm.

I have the absolute HOTS for evolution’s explanatory power. It still gives me the howling fantods after all these years.

Yummiest of all, the discovery of mirror neurons also provides a tantalizing hypothesis for why we seek to be good without gods. Without the hard-wired ability to feel what someone else feels, we really could be islands unto ourselves, indifferent to each other’s pain and suffering. Picture one population of mutually indifferent, self-centered creatures, and another in which empathy is the norm. Which population is going to survive to pass on its genes?

Oooooh, Darwin honey. Explain that to me one more time.

And look where we are now — we backed straight into that moral foundation. The single most powerful human moral imperative is the Reciprocity Principle: TREAT OTHERS AS YOU WOULD LIKE TO BE TREATED. Christians may recognize their Golden Rule in there, but its origin is much older and its presence much more universal, from Brahminism (“Do not unto others what would cause you pain if done to you”) to Buddhism (“Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful”) to Humanism, clunky and wordy as usual (“Humanists acknowledge human interdependence, the need for mutual respect and the kinship of all humanity”) to Wicca (“Ain’ it harm none, do what thou wilt”).

I’ve always felt that empathy was a natural enough thing — but for those who need convincing, mirror neurons are the ticket. It takes very little to see, in this remarkable neural system, the root of empathy, sympathy, compassion, conscience, cooperation, guilt, and a whole lot of other useful tendencies. It explains my kids’ tendency to wither under disapproval, and the weight in my own chest during the recent fracas with my publisher. Thanks to mirror neurons, the accused feels the condemnation all the more intensely. Empathizing with someone else’s rage toward you translates into a kind of self-loathing that we call guilt or conscience. Once again, no need for a supernatural agent.

If nothing else, mirror neurons can put some meaningful data into one of those unbearably fuzzy old beer-besotted college dorm room discussions: Are humans inherently good, or inherently evil? We have tendencies toward selfishness, of course, but survival also requires tendencies toward cooperation. Mirror neurons don’t guarantee good behavior, but what does? What they do is all they need to do for our survival as a species: By allowing us to feel what others feel, they incline us away from pure selfishness and toward mutually beneficial behaviors, which works out well for everybody.

It’s just one more reason we’re still here, after all these years.

onward and upward

I’m going to show an uncharacteristic degree of self-control by commenting no further on my posting, deletion, revision, reposting, and redeletion of a brief satire about recent events in the book’s release. Even my apology was deemed problematic by certain people wiser than myself in such matters, so I just can’t go into it any further. Sorry, I know curiosity is probably killing both of my loyal readers, but life is too short and potentially fun to get mired in nonsense. Onward and upward.

Coming up instead: a fascinating entry on empathy and mirror neurons in which no corporate self-esteem is damaged! Stay tuned!

the iWord

[Creepy cover image from The Manipulated Mind:

Brainwashing, Conditioning and Indoctrination by Denise Winn.]

There’s a smart and funny dad-blog across the pond (no no, the other pond — veer left and go long) at the Sydney Morning Herald called “Who’s Your Daddy.” Author Sacha Molitorisz blogged about parenting and religious issues in WYD the same week as my SMH interview about PBB.

(Okay…pulling back from the abyss of acronyms…)

How religious Sacha is himself I dunno — but with advice like this, who cares:

Both Jo and I want to give [our daughter] Edie the best education possible, and both of us want her to learn about religion and spirituality. Ultimately, we want her to make up her own mind about her beliefs, but we want her to do so from a position of knowledge, not ignorance. Ideally, we’d love her to know a little about Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and more.

The question is: Which school is going to give Edie a balanced education about the world’s religions? In fact, is there such a school? Jo went to a Catholic high school, where she learnt, predictably enough, about Catholicism. I went to a secular public school, where I learnt nothing at all about religion. Perhaps the best Jo and I can hope for, rather than a school with a comprehensive spiritual syllabus, is a school that teaches some religion, and is unbiased in its lessons.

Edie’s a lucky kid. She’s growing up with a far-better-than-average chance to think for herself when it comes to religion, since she has parents who know that broad-based religious literacy without indoctrination is an indispensible part of that.

Sacha did get me a bit tetchy with this passage:

McGowan says that in his family there are no taboo subjects when it comes to spirituality. As he says, “My goal is to keep [my kids] open and off-balance until they are old enough to start deciding on their own position”….McGowan’s position raises an irony that’s often unspoken. People such as McGowan think they’re being completely impartial and inclusive in their approach to religious instruction. But the child of an atheist is being just as indoctrinated as the child of a devoutly religious person….One dad’s atheism will probably influence his child as profoundly as another dad’s Greek Orthodoxy – and a child will ultimately either absorb that spirituality or react against it.

I’d have nodded uncontrollably at that passage if Sacha had modified a single sentence:

But the child of an atheist is at no less risk of being indoctrinated than the child of a devoutly religious person…

The difference between the two phrasings is huge. The first is unintentionally cynical. It implies that there’s just no way to raise a child without indoctrination. Yet Sacha’s description of his own plans for Edie’s religious instruction sounds remarkably free of the iWord.

His plans also sound remarkably similar to mine.

What Sacha is recognizing is the inevitability of influencing our kids. There’s no use denying that, nor would I want to. I hope to influence my kids positively by what I do and say. And I wince in recognition of the dark side of influence when my less attractive mannerisms, words, opinions, and attitudes begin surfacing in the kids. Nothing quite as horrifying as seeing yourself through the glass of your children, darkly. Likewise, there’s little as thrilling as seeing positive seeds you’ve planted — patience, empathy, gratitude, honesty — bearing lovely fruit in a moment that could have gone either way.

Influence is sometimes passive and sometimes a matter of intentional teaching. In those moments of active instruction (“Don’t throw your gum wrapper out the window!”), we try to follow up with reasons (“What if everybody did that?”) to help the kids develop independent moral judgment. The first sentence only proscribed a single act. The second invoked a universal principle that can be applied again and again. That’s influence at its best: Teach a man to fish, and all that.

My kids know — and are surely influenced by — my religious views. But I go to great lengths to counter that undue influence, keeping them off-balance while they’re young so they won’t be ossified before they can make up their adult minds:

“Dad? Did Jesus really come alive after he was dead?”

“I don’t think so. I think that’s just a made-up story so we feel better about death. But talk to Grandma Barbara. I know she thinks it really happened. And then you can make up your own mind and even change your mind back and forth about a hundred times if you want.”

That’s influence without indoctrination.

Indoctrination is another ball of cheese entirely. Princeton’s WordNet hits it right on the head, in my humble:

INDOCTRINATION (n.) Teaching someone to accept doctrines uncritically.

Here’s one of my own:

INDOCTRINATION (n.) The pre-chewing of someone else’s intellectual food.

“Because I/God/the Pope/Scripture said so” is the frame in which indoctrination is most often hung. Non-religious parents should be less likely to parent by indoctrination, if only because they’ve seen the iWord from the outside. Yet many fall into it anyway. Silly monkeys. Take a lesson from Sacha, who has recognized the iWord from inside religion.

At the heart of indoctrination is the distrust of reason. The indoctrinator simply can’t entrust so important a thing as [insert doctrine here] to the process of independent reasoning.

But freethought parenting should have confidence in reason at its foundation. We ought to know that either reason leads to our conclusions or our conclusions ain’t worth the neurons they’re written on. Teach kids to think independently and well, then trust them to do so. And part of that education is encouraging them to resist indoctrination of all kinds — even if it’s coming from Mom and Dad.

[N.B. Wikipedia also has a very thoughtful entry on indoctrination.]

vive la différence

First, a bit of news: We’ve arrived in Atlanta and tentatively found our new home, and (following the Newsweek article) Parenting Beyond Belief hovered between 350 and 700 on Amazon — the top two hundredths of a percent — before cooling off a bit.

More on all that later. Right now I’ve a blogligation to fulfill. Several weeks back, a reader asked a great question: Why do I consider the line between “religious parenting” and “nonreligious parenting” to be meaningful? Isn’t the kind of parenting I advocate (unbounded questioning, a scientifically-informed, evidence-based worldview, questioning of authority, rejecting the notion of “sinful thoughts,” developing moral judgment instead of simple rule-following, etc. etc.) really just “good parenting”? Am I really saying that religious parents can’t do these things?

No, I’m not saying that — partly because I can’t.

Really. I can’t. It’s an absolute statement, you see — and twenty years immersed in the liberal arts, first as a student, then as a professor, left me completely incapable of making an absolute statement. (Well, not completely.) Go back and read my blog so far. I constantly use qualifiers like most, many, almost, and some because I am painfully aware that all generalizations are wrong.

Well…not all.

There is nothing that religious parents “can’t” do, nothing that is the exclusive purview of secular parenting — just as there is nothing that religious parents can achieve that I can’t.

So why make the distinction at all, then? Why describe something called “secular parenting” if it’s pretty much the same as good religious parenting?

Because though we can end up pursuing the same ends, they really aren’t the same. There is a profound difference in the context — the space in which religious parenting and secular parenting happen.

Both secular and religious parents can raise kids to value fearless questioning, require genuine evidence, question authority, and reject paralyzing ideas of “sin” and the demonization of doubt. But one of these worldviews encourages and supports those values, while the other discourages them. One lends itself to them; the other chafes against them.

(Psst: I’ll tell you which is which in a minute.)

Being a freethinking Christian is something like being a pro-choice Republican. Opposition to legalized abortion is one of the central, defining policy planks of the Republican Party platform. There are pro-choice Republicans, of course, but they surely recognize that their pro-choice position is at odds with their party’s ideology. They can still do it, of course, can still hold that dissenting position within a Republican identity, but when it comes to that issue, they’ll be swimming upstream, struggling against one of the defining values of their group.

Same with pro-war Quakers, acrophobic window washers, and Danny, the claustrophobic tunneler in The Great Escape. “Jeez, good luck with that” is about all I can think to say.

My hat’s off to any religious parent who encourages unrestrained doubt, applauds fearless questioning and rejects appeals to authority. Such religious parents are salmon swimming against one helluva mighty current. At the core of religious tradition and practice are the ideas that doubt is bad, that certain questions are not to be asked, and that church and scripture carry some degree of inherent authority. This varies among the denominations, of course, but some degree of these three will be present in virtually every flavor of the faith. (Five extra points for each weasel word or phrase you can find in that sentence.)

The great glory of secular parenting is that it embraces several key values that religion has traditionally suppressed and feared, allowing parents and children to turn away from that pointless, mind-juddering dissonance, to dance in the light of knowledge and to revel in questioning and doubting as the highest human callings, rivalled only by love.

Parenting Beyond Belief is about the ecstasy of parenting from a worldview that supports and encourages some of our most deeply-held values. That, then, is the difference. And vive la it.

As for those religious-parent salmon, swimming against the unhelpful currents of church tradition, heed this wisdom from the Book of Dory — just keep swimming, follow your conscience, and do what you can to help others see the light: