Religious Diversity and Tolerance at Home

by Pete Wernick

Contributing author, Parenting Beyond Belief

Pete and Joan Wernick in performance

I’m the lone humanist in my household. My wife Joan is a committed Catholic, and our teenaged son Will, though not formally aligned with any religion, does believe there’s a God. People are understandably curious, wondering, “How do you make it work?” Here’s the story:

Joan and I met and became a couple thirty years ago this summer. I was then, as now, an atheist—hadn’t yet discovered the term “humanist”—and she was in “searching” mode, having made a break from her Catholic upbringing. While not an atheist, she supported my penchant for collecting and writing non-theistic life-affirming meditations and philosophies. At our wedding five years later, the ceremony we wrote and read to our family and friends was full of heart and free of theism.

Several years later, Joan started reconnecting with her Catholic roots. Though this shook our shared foundation, our long-term commitment and our new parenthood motivated us to make it work. Without realizing it, we followed mediation guidelines: Make a mutually agreeable “plan of practices” to follow, and stick with it. Limit philosophical debates that divide and irritate.

One of our first positive steps was to agree on how to raise our son re religion. We would each let him know our outlook and eventually encourage him to make his own choices. (Lo these seventeen years later, it’s now pretty obvious that he’d have done that anyway.) We would phrase our beliefs not as certainties (e.g. “God wants you to…” or “There is no God”), but as beliefs (“I believe that God wants you to…”, or “I don’t believe in God”). We asked our relatives to respect this style, not stating opinions as “truths” to Will, but only as their beliefs, if at all. Understanding that their cooperation was a way to support our marriage, thank goodness, they complied. As for the moral code we’ve tried to teach, we don’t disagree: Caring and respect for others is the guide.

Naturally, when discussing religion with Will, I would try my best to be convincing. Along with discussing why it’s important to be a good person, I would tell him that the idea of an invisible father who controls everything just doesn’t make sense to me. Though he never bought church doctrine, since he was small he has maintained: “Then how did all this get here?” To me, the only answer to that is “No one knows”—but “God did it” works for him.

Despite Joan’s and my cooperation, the increasing differences created a painful sense of loss for me. While she still appreciated my positive philosophy, she was now regularly going to church and embracing beliefs and practices for which I had little feeling or respect. I sometimes felt I just couldn’t handle it. I went to a counselor and did a lot of complaining. The counselor’s refrain was, “What are you going to do?” I took a hard look at ending the marriage, and realized how much I had, and how precious it was. Joan is a wonderful person with a big heart and a great deal that I can learn from. We still agreed on so many things, and we had all that shared history. I decided to find more ways to make it work.

There will always be differences between people. Even small differences can cause friction, even between otherwise like-minded people. The key is keeping control of the friction, not eradicating the differences. Some of our understandings:

• Agree to disagree when possible.

• Emphasize common ground.

• Don’t unnecessarily put something hard-to-take right in the other’s face.

• Leave the door open to respect as much as possible of the other person’s outlook and practices.

All of the above have helped.

From the start, I was relieved that we agreed to avoid children’s books and movies with religious themes. Joan was glad for the chance to share Christmas and Easter services with Will and didn’t mind my occasionally taking him to Unitarian church. Either of us talking religion with others is best done away from common areas where it might get on the other’s nerves. Family activities, even the art and pictures we display on the walls of our home, reflect the things we both love: nature, music, togetherness, good memories. Atheist cartoons and pictures of the pope go in our respective rooms.

This isn’t to say we avoid discussing our beliefs. But when we do, we take care to be respectful and to back off when it is going nowhere (as it often does). Agreeing to disagree actually provides some relief. As we abandon the conversation, I feel that we are affirming peace in our house, which I appreciate and cherish. And we can go right from there into some more harmonious part of our common ground. It’s a choice I’m happy to make.

There’s a bright side to this in-home diversity – the benefit to a kid of seeing parents and kids coexist and be loving despite disagreements, or even a different set of core beliefs. Learning to accept some dissonance is good practice for later life. Good people can disagree and still love.

Beyond that, this family harmony suggests that the real core beliefs have more to do with “what is good behavior” than with what’s up in the sky or after death, or what happened 2000 years ago. Absence or presence of mythology needn’t necessarily lead to disharmony any more than a difference in hobbies or in favored sports teams. Why should a spouse’s dedication to something I find uninteresting – be it the Detroit Tigers, NASCAR, 19th century English novels, or the Catholic Church – unsettle me? (Well okay, it’s not really that simple – but I gladly take private comfort in this construct.)

Joan is from a large family, and their occasions are often infused with religion, which at times makes me squirm. But I have also cultivated an appreciation of the benefits her family derives from Catholicism – their deep sense of charity that fuels an ongoing penchant to do for others, their ability to forgive and go on from upsets, their ability to accept and include, refraining from judgment. When their religion calls on them to embrace supernaturalistic myths or ideas I’m at odds with, I can at least try to tie the pieces together as part of one cloth, as varied as the entire human condition. And I can also just literally look the other way, or even flat out leave the room if I can’t take it. Joan is more at ease with my views, and even reads my Family of Humanists columns with interest and some good suggestions.

The above set of practices and guidelines is far from perfect. It has been a stretch for me, a person with perfectionist tendencies, to learn these ropes. But that’s all the more reason to do it: learning flexibility, learning to accept. And religious diversity will not be the hardest challenge to accept as I grow older.

Having made progress in this area has given me some deep satisfaction. At first I wasn’t sure it was possible. How could I put up with the pain? It turns out to be quite possible. I find myself thinking, if we can learn to do this in our house, maybe there’s hope for the Israelis and Palestinians, the Indians and the Pakistanis. Peace is a wonderful thing. I work at it because it’s worth it, and I’m still at it. This past June we celebrated our 25th anniversary.

Bronx-born Coloradoan Pete Wernick earned a PhD in Sociology from Columbia University while developing a career in music on the side. His bestselling instruction book Bluegrass Banjo allowed “Dr. Banjo” to leave his sociology research job at Cornell to form Hot Rize, a classic bluegrass band that traveled worldwide. Pete served as president of the International Bluegrass Music Association for fifteen years.

Pete, his wife and son survived the disastrous crash of United Airlines Flight 232 in Sioux City in 1989. A Life magazine article following the crash identified Pete as a humanist and noted that he didn’t see a supernatural factor in his survival. An atheist since age fifteen, Pete was president of the Family of Humanists from 1997 to 2006. Today he continues to perform, run music camps nationwide, and produce instructional videos for banjo and bluegrass.

This essay first appeared as the President’s Column in the Family of Humanists newsletter, Aug/Sept 1999.

meet you @ the forum

Recent snapshot of secular parents milling about the PBB Secular Parenting Discussion Forum

Had a nice interview yesterday with a religion news wire service for an upcoming syndicated article on secular parenting — but I think I made it all sound too easy. I described ways we buffer our kids from this and that, how we expose them to this and that, and how the interactions our family has had with religious folks generally involve fewer pitchforks and torches than we often fear.

“So if there are so few problems,” the reporter asked, quite sensibly, “what’s the need for the book?”

D’oh!

I do that sometimes. In an effort to take the temperature down a notch, I undersell the very real challenges. I explained that the biggest problem is at the larger level — community and society — which continues to demonize and marginalize nonbelievers and to consider them, among other things, unworthy to hold office or to have a voice in important ethical issues. But it’s also the case that Becca and I have gotten better at anticipating problems and raising our kids in ways that minimize the turbulence at the everyday level by applying many of the ideas in the book. Grappling with the issues has made us better secular parents, which makes things go better on that everyday level — which can lead to improvements on the larger scale.

Because of PBB, I’m becoming something of a Dear Abby of secular parenting. Every week I get emails asking for advice on this or that. How to help the second grader who is being religiously bullied at school. How to deal with a twelve-year-old boy who’s developing an unmoderated arrogance toward all things religious. How/whether to keep Grandma from evangelizing the kids. Whether/how to celebrate Christmas. Whether to go through with the baptism the relatives want. How to get a five-year-old started on understanding evolution. How a mom can talk to her daughter about death when she’s not all that keen on it herself.

In the beginning I’d type out my thoughts, but in recent months I’ve started referring parents to appropriate threads in the Parenting Beyond Belief Forum. Over 200 secular parents are registered and trading ideas on that board, which now has more than 200 topics and 1200 posts.

Last week I got an email asking how best to handle religious relatives who insist on saying grace when they come to your house. This is one I answered on the Forum a while back. An excerpt of that Forum thread:

HappyDad from California wrote:

Here’s a situation I figure must be common. We have a lot of family in town, all churchgoers except for us, and we get together a lot for family events. When a meal is at our house, we start to tuck in without saying grace, and somebody (usually my sister, knowing exactly what she’s doing) says, in a wounded voice, “Aren’t we going to thank Jesus for this lovely meal?”

After an awkward few seconds, SHE will invite someone to do it. “Rachel, why don’t you lead us in prayer, honey.” She’s not trying to be disrespectful or embarrass me, by the way…she just honestly can’t pick up her fork until somebody checks in with jehovah.

Yes, I know it’s my house and I have the right to keep religion away from my table. I know that. But first of all, seriously, I always forget until the moment it happens, and then I’m thrown. And secondly, I’m asking how, precisely, I can do this. It isn’t always my sister; sometimes somebody else beats her to it, so I can’t just pull her aside and make the issue go away. And I really don’t want to insult their intentions, which I promise are good. But I don’t want superstition in my house, and I don’t like having to sit and pretend to pray in front of my kids.

They’re alllll coming over again early next week. Gimme some tips here, guys and gals! Thanks!

I replied:

Public prayer galls me for at least two reasons: it’s coercive, and one person speaks for everyone, assuming a uniformity that is never really accurate. It is also too often manipulative (“And may the Lord bless and protect those among us who have been making unwise choices lately” [all eyes go to cousin Billy]).

We have a family tradition that solves this problem and has become a special daily moment in and of itself.

As we sit down for dinner (every day, not just when there are guests), we join hands around the table and enjoy about a half minute of silence together. We’ve asked the kids to take that time to go inside themselves and think about whatever they wish — something about the day just passed, a hope for the next day, good thoughts for someone who is sick, or nothing at all. And yes, they’re welcome to pray if they’d like to.

But here’s the key: it’s a personal, private moment. We don’t follow it with “You know what I was thinking about? I was thinking about homeless children.” Otherwise it turns into a spitting contest to see who was thinking the most lofty thought. Kids will try this at first. Just nod and change the subject. Eventually they figure out that it really is a private moment, which changes the nature of it.

It’s become a daily watershed for us — a moment that marks the transition from hectic day to quiet evening. I love it.

When we have guests, we tell them (before anyone can launch into prayer) that we begin our evening meal with a moment of silent reflection, during which they may pray, meditate, or simply sit quietly as they wish.

And if you have to pull out the big guns, tell them you just respect the teachings of Jesus too much to disregard Matthew 6:5-6:

“And when you pray, do not be like the hypocrites: for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and on the streetcorner to be seen by men….when you pray, go into your room, close the door and pray to your Father in secret….”

That’s a red-letter passage, straight from the big guy. Tends to end the debate.

Several other parents replied as well with tips and thoughts. And that’s the beauty of it, of course. I don’t mind the emails one bit — I love them, really, they make me feel oh so terribly significant — but why not also drop in on the PBB Forum and tap 200 heads instead of one? Yes, now! Up the big marble stairs, turn right, through the blood sacrifice room, third door on the left.

_____________________________

[Also, psst: Don’t forget to check on the ten wonderfull things page once in a while. And keep sending your suggestions for wonder-full links for secular parents to dale {AT} parentingbeyondbelief DOT com.]

and then we played

I’ve sprinted upstairs to transcribe the following dinnertable conversation with my daughter Delaney, nearly six. The names have been changed to etc:

DELANEY: I was at Kaylee’s house today after school, and she said she believes in God, and she asked if I believe in God, and I said no, I don’t believe in God, and her face got all like this

and she said, But you HAVE to believe in God!

DAD [w/mouthful of grilled pork]: Mmphh fmmp?

DELANEY: And I said no you don’t, every person can believe their own way, and she said no, my Mom and Dad said you HAVE to believe in God! And I said well I don’t, and she said you HAVE to, and I said that doesn’t make sense, because you can’t like go inside somebody’s brain and MAKE them believe something if they don’t believe it, and she said do your Mom and Dad believe in God, and I said no, they don’t believe in God either, and her face did like this again

and she ran into her room and got a book.

DAD [mashed potatoes]: Mm bhhk?

DELANEY: Yes, a picture book, and she said you HAVE to show this to your Mom and Dad, it’ll make them believe in God!

DAD: Whu…

DELANEY: And I said, I don’t have to show them that book, and she said if you don’t show it to them and if you don’t believe in God, you can’t come to my house anymore!

[Mom and Dad’s eyes meet, eyebrows fully deployed.]

MOM [who (having been raised right) swallowed her potatoes first]: Then what did you say, sweetie?

DELANEY: She kept saying it, so I cried. And then I said my dad says its okay for people to believe different things, and you can even change your mind a hundred times! And she said okay, okay, stop crying, you can come to my house anyway.

MOM: And then what?

DELANEY: And then we played.

the Quéstion of Québec

Il est faux de penser que la religion rend la mort plus acceptable. À preuve, les rites funéraires sont marqués par des moments d’intense tristesse. Et la plupart des croyants ont peur de la mort et font leur possible pour retarder sa venue! Demandez-lui si elle avait peur avant de venir au monde. Elle risque de répondre en riant : «Bien sûr que non, je n’étais pas là!» Expliquez-lui que c’est la même chose pour la personne qui décède. Elle n’est simplement plus là. Il existe plusieurs façons d’apprivoiser la mort. C’en est une.

Accepter sa propre finalité est le défi d’une vie, et ça restera toujours une peur qu’on maîtrise sans jamais la faire disparaître totalement.

M. Dale McGowan, auteur de Parenting Beyond Belief

No no, come back! I haven’t really become sophisticated — except in the pages of the Montréal-based public affairs magazine L’actualité, which carries an interview avec moi as its November cover story.

I was interviewed last month by Louise Gendron, a senior reporter for what is the largest French-language magazine in Canada with over one million readers. A website Q&A (in French) supplements the print interview.

So why the sudden interest among the Québécois about parents non-croyants? It’s a fascinating story. Québec has historically been the most religious of the Canadian provinces. Over 83 percent of the population is Catholic — hardly surprising, since the French permitted only Catholics to settle what was New France back in the day.

But now Québec is considered the least religious province by a considerable margin — and without losing a single Catholic.

Non-religious Catholics, you say? Oui! French Canadians are eager to maintain their unique identity in the midst of the English Protestant neighborhood — and “French” goes with “Catholic” in Canada even more than it does with “fries” in the U.S. Yet educated Catholics — I’ve discussed this elsewhere — are the most likely of all religious identities to leave religious faith entirely. There is, by all accounts, a very short step from educated Catholic to religious nonbeliever.

In recent years, a very large percentage of Catholic Québécois have essentially become “cultural Catholics” — continuing to embrace the identity and traditions of the Church despite having utterly lost their belief. The most striking evidence is a referendum, five years ago, to transition the provincial school system from Catholic to secular. The referendum passed easily, and a five-year transition began in 2003. This year is the last year of that transition — and to the shock and surprise of many, the entire process has taken place with very little uproar.

Until now.

____________________________

“In recent years, a very large percentage of Catholic Québécois

have essentially become “cultural Catholics” — continuing

to embrace the identity and traditions of the Church

despite having utterly lost their belief. “

____________________________

My interview was going to be a good-sized piece, but two weeks ago (in the words of Louise Gendron), “all hell broke loose” in Québec as orthodox Catholic family organizations launched a coordinated media campaign attacking the secularization of the schools. At which point L’actualité decided to make the interview the cover story and enlarge the website Q&A.

Most “cultural Catholic” parents in Québec support the transition but wonder how to explain death, teach morality, encourage wonder — in short, how to raise ethical, caring kids — without religion.

Perhaps you can understand my sudden, intense interest in Québec, and why there is talk — very early talk — of a possible French edition of Parenting Beyond Belief, to be published in (vous avez deviné correctement!) Québec!

Nice Guys Finish–an interview with Hemant Mehta

The annual convention of the Atheist Alliance International (AAI) is coming up at the end of September in Washington, DC. Included on the be-still-my-heart roster of speakers are Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, Julia Sweeney, Daniel Dennett, and Eugenie Scott.

Oh, and me.

I’ll be the one in bobby sox and a poodle skirt screaming, “SAM!! Over HERE, Sam!! I have ALL your records!! I know all the lyrics to End of Faith, listen, listen: ‘The young man boards the bus as it leaves the terminal. He wears an overcoat. Beneath his overcoat, he is wearing a…’ OMIGOSH, HE BLEW ME A KISS!!” (Faint.)

But it’s another AAI convention that’s on my mind at the moment — Kansas City ’06, where I sat listening to an articulate and thoughtful twentysomething lad at the podium as he suggested atheists ought to show a friendlier face to the religious world than we often do.

He made the case that intentional ridicule and insult directed at religious folks are especially counterproductive. Included among his examples was the “Smut for Smut” campaign at the University of Texas San Antonio, in which atheist students offered to trade pornography for Bibles.

“BULLSHIT!” screamed a sixty-ish audience member near me. The speaker continued, so the guy in the audience stood and yelled again. “THAT’S BULLSHIT! Those people have courage, they’re out there fighting for your rights, and you ought to be honoring their courage!! For you to stand up there and…”

You get the idea. A kind of atheist “Support Our Troops” thing.

The speaker, seemingly unrattled, simply expressed his reasons again, while Mr. Bullshit sat, shook his head side to side, and bitched to his tablemates.

It was a powerful moment, a genuine clash between different visions of atheist activism. Both seek to move atheism out of the margins, but only one sees force of one kind or another as the way to get there.

Mr. Bullshit isn’t alone in thinking that a two-by-four between the eyes of religious folks is a good tool for advancing freethought. But neither is the speaker alone in thinking otherwise.

A few weeks ago I received a heartfelt email from a gentleman who saw the Newsweek article about PBB and wanted to express his hope that it did not focus on combating religion:

What I fear is that the momentum there appears to be today [in the popularity of freethought books] will hit an impassable wall of resistance because most people will still see Atheists and Agnostics as negative-oriented “spoilers”….I just don’t think we’re going to win this ideological war with criticism, argument, attack, and anger….I believe the only way Atheists and Agnostics will ever grow as a group is by offering people a joyful, wonderful alternative to religion….And in our own lives we should lead by example of how fulfilling one’s life can be without God.

Sadly, I can’t seem to find people who want to take this approach. I do not believe we can get [out of the margins] by attacking religion and people’s belief in God. Nor can we get there by assuming that Believers are usually stupid, ignorant, or brainwashed. I believe we can get there by offering an alternative that is as viable as religion and belief in God. I believe we can also coexist with Believers.

I gently suggested that, if he couldn’t find others taking that approach, he should look a little harder. There are scads of people out there working toward exactly the vision he advocates. I offered, as a shining example, this guy:

In addition to being the aforementioned speaker in Kansas City, Hemant Mehta is the author of The Friendly Atheist, one of the sharpest, wittiest, and most informative blogs on the block; author of I Sold My Soul on Ebay, a thought-provoking and fresh look at religious belief through a nonbeliever’s eyes; chair of the board of directors of the Secular Student Alliance; and one of the foremost advocates of nice-guy atheism. He was kind enough to take a moment to answer a few prying questions.

Q

Why so friendly?A

Most religious people I know aren’t doing the things atheists are so opposed to… They’re not pushing an anti-evolution agenda. They’re not trying to stop gay marriage or impede embryonic stem-cell research. But they do pray and they do have faith in God. I wholeheartedly accept that they are wrong in their beliefs, but they’re not the major problem.I think we can reach out to those people and get them on our side. We need to do that. They already are on our side about most social issues and they believe in separation of church and state. Those concerns are much more important to me than their belief in the supernatural.

And the way to reach out to those people is to be friendly and to explain who I am, why I’m an atheist, and why that’s ok. It doesn’t mean I agree with their beliefs or that I am conceding anything to them.

Hemant is one of those rare people with whom I seem to agree constantly. You know the type? Read his blog and see if you don’t find yourself nodding like a damn bobblehead.

Q

I know some non-religious folks (UUs, mostly, come to think of it) with a sort of “universal friendliness” toward religion and religious ideas. You seem to strike a more careful balance, discerning between those things that deserve respect and those that deserve critique. How do you strike that balance?A

If their beliefs are personal and they’re not hurting anyone else, I’m not too worried about it. Sure, I can debate with the people and try to convince them that they’re wrong, but it’s not going to do much good. Even if you “win” the argument, you haven’t accomplished much.On the other hand, when supernatural beliefs start causing harm, we have a problem. I’m referring to terrorists who act in the name of God, “psychics” who con vulnerable (and gullible) people out of their money, or certain Christian leaders whose clout helps bad legislation to get passed. Those people deserve to be criticized. Their faulty thinking and ignorance — due to their faith — is hurting others. By calling out their beliefs, we’re helping others who may be victims of their actions.

Q

Atheist meetings of all kinds, from local chapters to national conventions, are often far too self-congratulatory for me. I’d like to see the same critical balance struck when we look in the mirror. What is the biggest whack in the head (or two or three) you’d like to give to atheists as a group?A

Here’s a story for you. There was recently a poll on the website for Larry King Live, asking people about their religion affiliation. Initially, “Christians” were in the lead and “atheists” were in second. Some websites, mine included, encouraged atheists to submit a vote in the poll. A day later, the number of atheists was *overwhelming* — apparently, we were over 70% of the population.Obviously, that’s not a scientifically accurate poll. But as one astute commenter mentioned on my blog, the results showed that we can get atheists to work together when it comes to irrelevant stuff, like this poll. When it comes to “rallying the troops” during election time or supporting national organizations who can speak on behalf of atheists on a large stage, we’re pathetic. I wish we could get our act together and convince other atheists that by ourselves, we’re not going to be able to accomplish much. We won’t be respected or accepted. But by supporting common causes and like-minded organizations, we could change that.

It’d also be nice if atheists would work harder at pointing out the benefits of a Godless worldview (as opposed to a religious one) and how you don’t need religion to be a good, moral, happy person. Instead, we just find joy in telling religious people how stupid they are. It gets us nowhere. But it does create more enemies.

Q

And how about the other side — I mentioned the heckler in Kansas City. Do you get much of that kind of flak from atheists who think you’re too accommodating of religion?A

The flak I get isn’t as bad as the Heckler 🙂 There are some atheists who think I’m too easy on religion. We may hold the same (non-)beliefs, and I’d say we also have the same passion for atheism, but like I said, I don’t think we’re focusing our energies where we should be, and they disagree.One thing I do want to point out: I get very *little* mail from Christians who tell me I’m going to Hell. That was very surprising to me. Not all Christians love what I wrote in the book, but most of them write very civil emails. I was told by other atheists to expect a barrage of angry Christian letters, but it never happened. Most Christians that write me resonated with the tone of the book.

Q

You know, I heard the same dire warning and got the same civil result. I think we pay so much attention to the nuts that we begin to expect that of all religious folks. Okay, another question. Give me two visions of the future, 50 years down the pike—one pessimistic, the other optimistic. You’re in your late seventies, I’ve been dead for 49 years, the Hilton Administration is in its third term. What’s the religious state of affairs in the U.S.?A

Pessimistic vision: You’re dying in a year, and I’m supposed to be pessimistic?! 🙂Okay—the world in this state wouldn’t be very different from where it is now. Our government may not officially be a theocracy, but the Christian Right has the power to make decisions for all of us. We’ve made no progress in obtaining rights for all people. Scientific research in the field of biology is all but halted because we can’t get federal funding for the most promising research there is. And I wouldn’t be surprised if abortion was made illegal.

Optimistic vision: Religion’s not going to go away, but ideally, in 50 years, I could see a country with a higher percentage of atheists (from ~15% now to possibly 30% in the future). We would have more seats in local and national government. We’ve helped acquire rights for all people and passed legislation that helps all people, religious or not. We’re not interfering with the private decisions of Americans, as long as they’re not stopping anyone else from living their own lives as they wish. And when a person says publicly, “I’m an atheist,” no one flinches. I think that’s entirely within reason. But it won’t happen if atheists continue acting the way we have been for so long.

Q

One more: how’s I Sold My Soul on Ebay doing?A

It’s going well… I have yet to see exact numbers (in terms of sales) but there is a lot of response from people who have read the book. Many bloggers and mainstream media have written about it, and there are still some projects stemming from the book in the works. It has also helped me transition into writing my blog, which I probably would not have started without the eBay auction. At many atheist conventions I’ve gone to since the auction, more people have heard about my website than the book! And I think that’s wonderful; it just speaks to the message I’m trying to convey, that we could achieve more success with a “friendlier” image.

Helluva guy, don’t you think?

One of the trickiest bits to negotiate in raising kids without religion is engendering the right attitudes about religion and religious people. Some aspects of religious belief deserve a helluva lot of loud and direct critique. I want them to learn to do that fearlessly, like Harris and Dawkins. But other aspects and actions deserve loud and direct applause. I want them to learn that as well [LIKE DAWKINS AND HARRIS. More on that later]. Discernment is called for. While never hesitating to criticize religious malignancies, we should bend over backwards to catch religious folks being and doing good if we ever expect them to notice us being and doing good. It stands to reason.

I feel a coinage coming on: Let’s call that hemantic discernment.

No marginalized group in history has gained a place at the table by telling the majority it is too stupid to live, or by closing its eyes and telling the majority you better damn well be gone before I count to ten. Imagine the dead end that gay rights would have encountered if the movement spoke of working toward a world with no heterosexuals. Imagine the grinding halt to civil rights legislation if black Americans insisted that white be recognized as inferior to black. By instead seeking nothing more or less than a shared place at the table, these movements moved. Until we realize the same thing and extend a far friendlier hand to the more reasonable representatives of the (most likely shocked and surprised) religious majority, we will be deservedly stuck on the margins.

Don’t worry. People like Hemant just might manage to save us from ourselves.

this ain’t your grandpappy’s Atlanta

I spent the first Sunday morning in our new Atlanta home heaving worldly possessions from our PODS (Portable On Demand Storage, highly recommended) container to the garage in 95-degree heat. At 10 o’clock I caught the eye of a neighbor mowing his lawn. He nodded and smiled. I nodded and smiled. Not in church, eh? we said telepathically. That’s right, we each responded. Two sweaty joggers bobbed by, presumably not church-bound.

Nod.

Nod.

Standing in line at the post office last week, I counted accents. I heard 28 people speak long enough to take a reasonable guess. Several distinct New Yorkers (including one behind the counter), a Bostonian, a possible New Jerseyite, at least three Midwesterners, an English woman, an Indian couple, and two women from California. Others were hard to place but definitely un-Southern.

So how many of the 28 had even a trace of a Southern accent? Three.

Our realtor is from Indiana. Our neighbors on the left are from California. Across the street is Michigan, and next to her, upstate New York. The guy who fixed our phone cable is from Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

I’m beginning to see why Southerners call Atlanta the “New York of the South.” It ain’t just the skyscrapers — it’s the New Yorkers. We’re in North Fulton County, an area exploding with newbies from everywhere but here, many brought in by the Fortune 500 companies based in town.

And we’re in an area more diverse than the one we left in Minneapolis. Our immediate neighborhood includes families from Indonesia, Taiwan and Pakistan. The populations at my kids’ schools are 40% non-white.

This is goooood.

It’s not that Northern is better than Southern, non-white better than white, or non-religious better than religious. It’s sameness that’s the enemy. I REALLY don’t want my kids growing up surrounded by people who look and think and act just like they do. As a teenager, I remember barfing inwardly at the phrase “Celebrate Diversity!” — until I spent some time surrounded by conforming sameness and watched all of the grotesque pathologies that bubble out of that. I’m a white liberal nonbeliever, but I know better than to want my kids growing up in an area that’s all-white (been there), all-liberal (done that), or all non-believer (don’t even wish for it). I want a mix.

And here in the northern stretch of Atlanta, as a result of the infusion of difference in the past 20 years, my kids are going to grow up in a much more diverse and cosmopolitan place than I sometimes feared in the weeks leading up to the move, laying awake in a cold sweat, staring at a ceiling that kept turning into the Stars and Bars and imagining the new neighbors as some combination of this

…and this

Though these guys are surely around, they’re a helluva lot rarer than the worst of my sleepless Minnesota nights would have had me believe. Isn’t that usually the case? Don’t I usually find that late nights are the worst time to measure reality? So when will I finally learn to tell my insomniac fears, once and for all, to bugger off?

By clicking on the lights one at a time, I guess. All that to say: now that I’ve seen Atlanta with the lights on, I like it.

love and law

Jiminy Christmas! What were you thinking, letting me ramble on like that in the last post! 2100 words! Speak up when I do that!

But somewhere in among the concordances and Schenker graphs and my Aunt Diane’s potato salad recipe back there, I made a promise to look at the concordance for another kind of Christian parenting book, so here’s a coda.

Compare the concordances for (shudder) John MacArthur’s What the Bible Says About Parenting and another Christian parenting book called Parenting With Love and Laughter: Finding God in Family Life, or PLL, by Jeffrey Jones:

You may remember that a particular cluster of frequent words in What the Bible Says About Parenting set my teeth on edge last time — OBEDIENCE, OBEY, SIN, DUTY, EVIL, FEAR, AUTHORITY, DISCIPLINE, COMMAND, COMMANDMENT, SUBMIT, LAW, INSTRUCTION, etc. But of those 13 words, not a single one appears in the top 100 of the Christian parenting book by Jeffrey Jones.

On the contrary, the Jones book seems to favor more humane, loving language and ideas. The word choices in What the Bible Says About Parenting indicate a view of childhood as a period of numb, acquiescent discipleship. You’d think these two were coming at the world from very different points of view — and you’d be right.

You might even be tempted to say the concordance of PLL has more in common with Parenting Beyond Belief than either does with the other. You’d be right there, too. Of the top 50 words in Parenting with Love and Laughter, precisely half are also in the top 50 of Parenting Beyond Belief. But PBB shares only one quarter of its top 50 words with What the Bible Says. Coincidence? I think not. Common words, to a point, reflect shared ideas. MacArthur would surely be as thrilled as I am to be placed solidly in separate camps.

So how can two Christian parenting books differ so dramatically in their essences–at least so far as the concordances reveal?

Of Love and Law

I’ll let Bruce Bawer handle this one.

Author/commentator Bawer (Stealing Jesus: How Fundamentalism Betrays Christianity) wrote a piece in the New York Times ten years ago while the Presbyterians were tearing themselves apart over the ordination of gays — just like the Episcopalians have done more recently. It was a sharp and illuminating piece that instantly snapped the American religious landscape into perspective for me. Here’s a taste:

American Protestantism…is being split into two nearly antithetical religions, both calling themselves Christianity. These two religions — the Church of Law, based in the South, and the Church of Love, based in the North — differ on almost every big theological point.

The battle within Presbyterianism over gay ordinations is simply one more conflict over the most fundamental question of all: What is Christianity?

The differences between the Church of Law and the Church of Love are so monumental that any rapprochement seems, at present, unimaginable. Indeed, it seems likely that if one side does not decisively triumph, the next generation will see a realignment in which historical denominations give way to new institutions that more truly reflect the split in American Protestantism. — THE NEW YORK TIMES, 5 April 1997

Though Bawer is talking about Protestants, the same fault line runs down the middle of American Catholicism, between venomous literalists and social justice-loving practitioners of genuine agape–unconditional love. And I don’t think it’s hard to see which of the above books is in which camp.

Christians I know are too quick to dismiss the “church of law” as an aberration, something unfortunate but…you know… over there somewhere. And atheists are often just as quick to overlook the presence of the “church of love.” My major complaint with that side of American Christendom isn’t that they have supernatural beliefs. As long as they do good with them, who cares? My complaint is that the church of love does far too little to confront its ugly fundamentalist stepsister. Worse yet, it arms her by indiscriminately promoting faith as a value in and of itself.

ANYway

I think Bawer’s model is revealing, and I think the concordances back it up nicely — one from the church of love, the other from the church of law. Two very different brands of Christian parenting are in play there — one with which I can surely find plenty of common ground, and the other…well, not so much.

The central point of PBB, as noted in the Preface, is to demonstrate for parents “the many ways in which the undeniable benefits of religion can be had without the detriments.” There are some things to emulate, adopt, and adapt from religious parenting into the religion-free model — and the place to look is in the church of love, not law.

(785 words. That’s the ticket.)

The distiller’s art

Distillation’s been on my mind lately — the art of condensing something ungraspably large into a graspable essence. I mentioned Carl Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar a few weeks ago, a distillation of universal history that instantly focused my understanding of just how recent we are — and how small we are, and how deep and silly our delusions of bigness are.

Distilling space

Here’s another distillation of a sort:

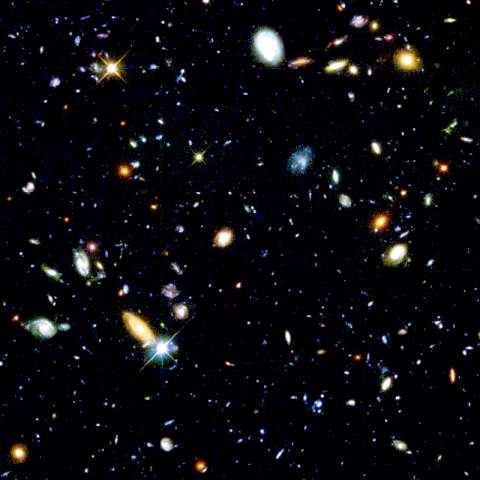

This image, called the Hubble Deep Field, must be the greatest picture of all time, a deep space image by the Hubble Telescope. How much sky does this represent? Imagine a dime held 75 feet away. The portion of the sky that dime would cover is the portion represented here. And it’s a patch of sky that appears essentially empty when viewed by ordinary telescopes. Most of the dots of light are not stars but galaxies. And this is one infinitesimal dot of space.

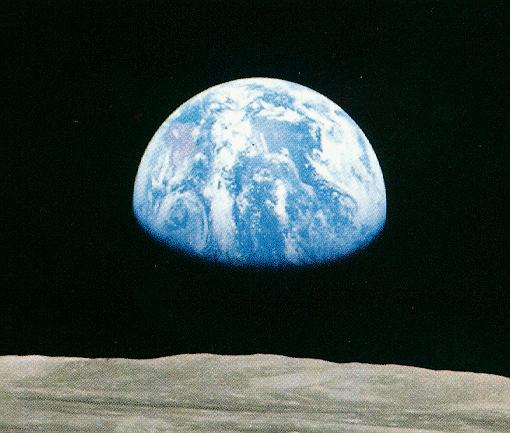

The Hubble Deep Field is my laptop background, and I sometimes find myself staring at it for ten minutes at a whack. It rivals Voyager’s famous “pale blue dot” photo and the first glimpse of Earthrise from the Moon for the granting of instant and lasting perspective for those who are awake:

You are here: The tiny dot is Earth viewed from Voyager II.

The 1968 paradigm rattler.

I love the particular headrush you get from this kind of distilled reality, the epiphany (sorry, it’s the best word) that can be achieved by snapshots capturing essences otherwise too large to grasp. In a single glance, I GET it.

Distilling time

Here’s another one:

That won’t mean anything to you normals, but having spent 25 years studying or teaching music theory, it’s something that makes me swoon. Music is notoriously tricky to get your hands on. Visual art is form and color arrayed across space, so you can snap on the rubber glove and it’ll hold still for the examination. Music, by contrast, is sound arrayed across time. Time is its body, so you can’t get it to hold still without killing it.

“If you try and take a cat apart to see how it works,” said Douglas Adams, “the first thing you have on your hands is a non-working cat.”

An Austrian music theorist named Heinrich Schenker developed a method for reducing a complex and ever-moving piece of music into a graspable snapshot. The chart above is a Beethoven string quartet movement of nearly 400 measures reduced to its essence. Foreground, middleground, and background, harmony and melody, it’s all there.

And–it’s not all there. Schenker didn’t intend this to replace music, but to give a little window of understanding, another way to GET it. I love to listen to Beethoven quartets, and I love to understand them as well. Then listening while understanding — don’t get me started.

Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar, mentioned above, is another time distiller, of course.

Distilling thoughts

Books are another tough nut to crack. By the time you get to the end of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, or The God Delusion, or Left Behind #13 — Kingdom Come, the sense of what a given book was “about” can reasonably vary from person to person. A friend reads Dawkins and hears a constant stream of invective. I read Dawkins and hear a constant stream of reasoned argument. No point saying one of us is definitively right or wrong. But there is one kind of snapshot distillation that I think sheds some interesting light — the concordance.

One type of concordance is a list of all the words appearing in a given book. Not the same as an index, which is a list of all concepts, whether or not they appear verbatim in the book. Somewhat subjective, the index. A concordance simply counts and reports. The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, for example, includes a long concordance that is misnamed “Index.” In it, you can find the apparent only significant use of the word “maggot-pie” — by Shakespeare, who else — and learn that the great quotesmiths have preferred to go on about love (586 times) more than hate (72 times). That’s nice.

But there’s another kind of concordance, one that can grant a bit of that snapshot distillation I’m on about. This kind records the most frequent words in a book.

If you hate “reductionism” — I myself happen to have a lifelong schoolboy crush on it, dotting its ‘i’s with little hearts as I write its name a thousand times on my three-ring binder — but if you hate it, you’ll hate concordances. They don’t reveal everything about a book, of course. If a concordance says the word MEAN appears 632 times in a book, does that indicate an obsession with hostility, or with significance, or with mathematical averages? And even if it is about hostility, is the book fer it or agin it? Maybe “mean” is always preceded by the phrase please don’t be.

The Hubble photo doesn’t tell us everything about the universe, either. It just gives us an insight, a new way of seeing it. Same with the concordance.

(Okay, the casual readers have long since gone. As a reward for the rest of you, here comes the point.)

I don’t know whether you’ve noticed, but for the past several months, Amazon.com has been sprouting new features like a house afire. My favorite new feature is, of course, the concordance. The 100 most common words in a given book are arrayed in a 10×10 block with font sizes varying by frequency. Huge-fonted words appear a lot, medium-fonted words etc. You get a fairly powerful sense of content, approach, and tone at a glance. I daresay I could show you concordances for books by Benedict XVI and Lenny Bruce and you’d know which was which — and which you’d rather read. (No no, don’t tell me, I’m keen to guess.)

Here, for example, is a concordance for one of my favorite recent books. Just looking at those hundred words makes me want to read it a fourth time.

The Point

Below are concordances for two parenting books, with the 100 most common words in order of frequency (in batches of ten for easier reading). One is about raising kids using biblical principles; the other is about raising kids without religion. See if you can tell which is which, and whether the concordances reveal anything about content, approach, and tone:

BOOK A

1-10: children—parents—god—child—love—own—husband—family—lord—word

11-20: wife—teach—heart—sin—christ—father—need—life—things—even

21-30: kids—should—man—must—son—proverbs—parenting—mother—does—scripture

31-40: kind—wisdom—evil—first—church—shall—may—home—fear—authority

41-50: marriage—obey—christian—ephesians—law—work—right—come—principle—means

51-60: take—truth—wives—woman—time—true—good—himself—solomon—give

61-70: live—men—let—paul—role—society—duty—honor—commandment

71-80: obedience—responsibility—teaching—against—gospel—know—therefore—verse—discipline—people

81-90: submit—something—themselves—jesus—want—women—wrong—world—day—think

91-100: instruction—faith—always—attitude—command—ing—certainly—spiritual—genesis—now

BOOK B

1-10: children—god—parents—religious—time—people—child—good—things—life

11-20: family—religion—world—think—believe—secular—know—even—beliefs—may

21-30: years—questions—own—right—kids—human—death—reason—first—school

31-40: idea—need—day—should—ing—moral—see—live—want—new

41-50: book—help—now—find—say—take—work—answer—others—something

51-60: church—come—wonder—bob—values—age—friends—get—go—little

61-70: does—without—long—often—true—thinking—feel—stories—must—love

71-80: exist—part—give—important—really—animals—two—great—kind—might

81-90: humanist—best—look—seems—still—atheist—few—thought—mean—mind

91-100:kobir—different—though—meaning—experience—problem—always—fact—adults—ceremony

Book A is

Book B is

The first observation is among the most interesting: that these two books, though different in many, many ways, have the same top three words. Even more interesting is that the secular parenting book mentions God more often. Not entirely surprising if you think about it. The top four words in Quitting Smoking for Dummies are SMOKING, SMOKE, TOBACCO, and CIGARETTES.

Next we notice a few surprises, like the fact that the concordance program promotes the suffix ‘ing’ to the status of a word, and that a dialogue in my book ends us up with the speakers’ names — Bob and Kobir — at #54 and #91, respectively.

Right, right…the point

One of the first things I noticed in comparing the two is the relative importance of obedience. What the Bible Says About Parenting uses the word OBEY 66 times and OBEDIENCE 49 times, while the same words appear only six and four times (respectively) in Parenting Beyond Belief — even though PBB is almost exactly twice as long. As a percentage of text, these words appear twenty-two times more frequently in the religious parenting book than in the non-religious one. I find that revealing, though not exactly surprising. I want my kids to know how to obey, sure, but it’s sixth or seventh on the list of my hopes for them (as I’ve written elsewhere). Seems a tad higher on the list for What the Bible.

What about parenting books in-between? I looked at two current mainstream bestsellers, Parenting From the Inside Out and I Was a Really Good Mom Before I Had Kids — neither of which includes OBEY or OBEDIENCE in its concordance. Religion and obedience seem particular stablemates.

I’m dismayed, but again unsurprised, that love is #5 in WTB and #69 in PBB. To tell the truth, I’m relieved it’s in our top 100 at all. Freethinkers love no less, of course, but we spend most of our time talking about truth and generally let love take care of itself. Religious folks often do the opposite, talking of endless love and letting truth tag along if it can keep up. And lo and behold, THINK is #14 for us and #89 for them. Also high in our list are the lovely words QUESTIONS (#22) and IDEA (#31) — neither of which appears in the other list.

The presence of words like HUSBAND, WIFE, SON, MOTHER, and FATHER high in the WTB list might indicate that role divisions are important. None of these appear in the PBB hit parade, which I think indicates less emphasis on divided roles. Perhaps I’m reading too much into these things. (READER: No no, I think you’re onto something!)

The presence of EPHESIANS on the WTB list makes some sense, since the end of Ephesians lists several familial duties — ‘Wives, submit to your husbands as to the Lord,’ (5:22) ‘Husbands, love your wives’ (5:25). But the fact that EPHESIANS appears 64 times just baffled me — until I remembered one of the most chilling verses in the NT:

Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. Honor your father and mother — which is the first commandment with a promise — that it may go well with you and that you may enjoy long life on the earth (Eph 6:1-3).

The conditional phrase “that you may enjoy long life” is no metaphor: It refers directly to Deuteronomy 21:18-21:

If a man have a stubborn and rebellious son, which will not obey the voice of his father, or the voice of his mother, and that, when they have chastened him, will not hearken unto them; Then shall his father and his mother lay hold on him, and bring him out unto the elders of his city…and they shall say unto the elders of his city, This our son is stubborn and rebellious, he will not obey our voice…And all the men of his city shall stone him with stones, that he die.

(For those who insist the OT is no longer in force, that it was replaced by a “new covenant” in the NT, Jesus wants a word with you. Now.)

Neither Ephesians nor Deuteronomy appears in the PBB top 100. Phew. We write about how to talk to kids about death (#27), but these guys threaten them with it. Okay okay, not directly…but by quoting the hell out of Ephesians, some (not all) religious folks show their enthusiasm for ultimate punishments in no uncertain terms.

I could go on and on, pointing out the high frequency of words like SIN, DUTY, EVIL, FEAR, AUTHORITY, DISCIPLINE, COMMAND, COMMANDMENT, SUBMIT, LAW, and INSTRUCTION in WTB, and the absence of any of those in PBB’s top 100, and the wholly different brands of parenting implicit in such observations. I could. But it seems equally important to point out that not all religious parenting books share the numbingly authoritarian quality that the concordance of What the Bible Says About Parenting seems to bespeak. In fact, I’d like to show you another Christian parenting book that has almost NONE of the sad and disheartening earmarks of WTB, James Dobson, and the rest of that ilk. But I’m sleepy. Next time, then.

(Here’s the link to PBB’s Amazon concordance, btw.)

choosing your battles

I’m all Southern now. For proof, see last post, in which God and football are mentioned in the same breath.

Somebody emailed me to ask why exactly I’m not girding for battle over the inclusion of God as one of the four team values for my son’s public football league. Let’s suppose for a moment it was a serious question. When it comes to religious incursions into public life, how do you decide when to fight and when to let it be?

Since I edited Parenting Beyond Belief, I’ve heard stories of church-state violations that would make your fries curl: public school marquees with Bible verses, a public kindergarten teacher showing the bible-based Veggie Tales and reading from In God We Trust — Stories of Faith in American History, even a values assessment in a public high school that gave kids a lower values score if they didn’t attend church or believe in a “higher power.”

Like the aforementioned curly fries, some of these are small issues, some are medium — and some are SuperSize. To sort them out, it’s a good idea to think about why church-state separation exists. It does not exist to “avoid offending atheists.” Ed Buckner put it this way in Parenting Beyond Belief:

Many people do oppose separation of religion and public education, of course, but most do so because they lack good understanding of the principle and its purpose. The most common misunderstanding is that separation is designed to protect religious minorities, especially atheists, from being offended. Offending people without good reason isn’t ever a good idea, but that isn’t the point of separation. Separation is necessary to protect everyone’s religious liberty.

THAT is what separation is for. If I tell you I’m in favor of putting God back in schools, half of my relatives would cheer — until I announce that it’s Chac-Xib-Chac, the Mayan god of blood sacrifice, who will be worshipped, and the Mayan creation story that’ll be taught as true.

THAT is what separation is for. If I tell you I’m in favor of putting God back in schools, half of my relatives would cheer — until I announce that it’s Chac-Xib-Chac, the Mayan god of blood sacrifice, who will be worshipped, and the Mayan creation story that’ll be taught as true.

Suddenly I’m no fun at all.

Likewise, if I said our prayers would be specifically Catholic — that we would pray to Mother Mary and invoke the name of Benedict XVI each morning, for example — there’d be Protestants laying bricks in the principal’s office.

Nobody understood this better than Southern Baptists at their founding. They were a tiny minority then, you see, and didn’t want some majority vision of God forced on their kids. Here’s Dr. Ed again:

The Southern Baptist Conference understood the point so well that it included separation of church and state as one of its founding principles. The Southern Baptists adopted, in their “Baptist Faith and Message,” these words: “The church should not resort to the civil power to carry on its work….The state has no right to impose penalties for religious opinions of any kind. The state has no right to impose taxes for the support of any form of religion.” Only by consistently denying agents of government, including public school teachers, the right to make decisions about religion is our religious liberty secure.

But now that they’ve made it into the mainstream, why, they can’t quite remember what all the separationist fuss was about.

If I heard that a teacher at my kids’ school was advocating atheism — saying specifically that God does not exist, for example, and telling the kids they should believe the same — I’d be the very first parent demanding his or her head. Secular schools are not the same as “atheistic” schools. They are neutral on religious questions — and that, you careful readers of the Constitution will know, is the American Way.

Anyway, back to my boy’s football thing. Stu Tanquist (whose essay title I stole for this entry) offered a list of considerations in Parenting Beyond Belief:

When considering whether or not to challenge religious intrusion in our lives, there are many factors to consider:

• Is your child concerned about the consequences?

• Could your child be negatively impacted by the challenge? Might he or she be ostracized at school by teachers or students?

• If successful, how significant would the change be? Would it positively benefit other families and children?

• Could you and your family be negatively impacted?

• What are your chances of success?

• How much time and resources are required?

• Do you risk damaging existing relationships?

• Is this likely to be a short-term or long-term fix?

• Is legal action necessary?

• Are there other parents or organizations that could assist you?

• Are you bored? Do you really need the spice this will add to your life?

• Would it feel rewarding both to you and your child if you succeeded?

This list isn’t designed to spit out the “right” answer; it simply raises the right issues. “Damage to existing relationships” is unfortunate, but in some cases might be outweighed by “positive benefit [to] other families and children.” Read his chapter and you’ll see how Stu geared his own responses, sitch by sitch, as his daughter encountered religious incursions in her public education.

The most important point Stu makes is the importance of considering the child’s wishes. Pushing a point your child doesn’t want pushed might do far more damage to your parent-child relationship than the issue is worth.

In the end, the football thing was a no-brainer. Compared to the likely consequences — especially for the new kid — it just doesn’t matter enough. God is just being presented as a value — inappropriately so, yes, but the effect is mild. My boy isn’t being forced to pledge individual belief in God, as he was (repeatedly) in Scouts. And he’s less impressionable now, better able to think for himself, so I’m not concerned about him being unduly influenced by an admired figure like his coach.

There are certainly cases in which I would stand up — and have. This just isn’t one of them. I’d be interested to hear what you think about Stu’s list — if there’s anything you’d add or subtract, for example — and whether you’ve come up against separation issues and how you handled them.

the iWord

[Creepy cover image from The Manipulated Mind:

Brainwashing, Conditioning and Indoctrination by Denise Winn.]

There’s a smart and funny dad-blog across the pond (no no, the other pond — veer left and go long) at the Sydney Morning Herald called “Who’s Your Daddy.” Author Sacha Molitorisz blogged about parenting and religious issues in WYD the same week as my SMH interview about PBB.

(Okay…pulling back from the abyss of acronyms…)

How religious Sacha is himself I dunno — but with advice like this, who cares:

Both Jo and I want to give [our daughter] Edie the best education possible, and both of us want her to learn about religion and spirituality. Ultimately, we want her to make up her own mind about her beliefs, but we want her to do so from a position of knowledge, not ignorance. Ideally, we’d love her to know a little about Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and more.

The question is: Which school is going to give Edie a balanced education about the world’s religions? In fact, is there such a school? Jo went to a Catholic high school, where she learnt, predictably enough, about Catholicism. I went to a secular public school, where I learnt nothing at all about religion. Perhaps the best Jo and I can hope for, rather than a school with a comprehensive spiritual syllabus, is a school that teaches some religion, and is unbiased in its lessons.

Edie’s a lucky kid. She’s growing up with a far-better-than-average chance to think for herself when it comes to religion, since she has parents who know that broad-based religious literacy without indoctrination is an indispensible part of that.

Sacha did get me a bit tetchy with this passage:

McGowan says that in his family there are no taboo subjects when it comes to spirituality. As he says, “My goal is to keep [my kids] open and off-balance until they are old enough to start deciding on their own position”….McGowan’s position raises an irony that’s often unspoken. People such as McGowan think they’re being completely impartial and inclusive in their approach to religious instruction. But the child of an atheist is being just as indoctrinated as the child of a devoutly religious person….One dad’s atheism will probably influence his child as profoundly as another dad’s Greek Orthodoxy – and a child will ultimately either absorb that spirituality or react against it.

I’d have nodded uncontrollably at that passage if Sacha had modified a single sentence:

But the child of an atheist is at no less risk of being indoctrinated than the child of a devoutly religious person…

The difference between the two phrasings is huge. The first is unintentionally cynical. It implies that there’s just no way to raise a child without indoctrination. Yet Sacha’s description of his own plans for Edie’s religious instruction sounds remarkably free of the iWord.

His plans also sound remarkably similar to mine.

What Sacha is recognizing is the inevitability of influencing our kids. There’s no use denying that, nor would I want to. I hope to influence my kids positively by what I do and say. And I wince in recognition of the dark side of influence when my less attractive mannerisms, words, opinions, and attitudes begin surfacing in the kids. Nothing quite as horrifying as seeing yourself through the glass of your children, darkly. Likewise, there’s little as thrilling as seeing positive seeds you’ve planted — patience, empathy, gratitude, honesty — bearing lovely fruit in a moment that could have gone either way.

Influence is sometimes passive and sometimes a matter of intentional teaching. In those moments of active instruction (“Don’t throw your gum wrapper out the window!”), we try to follow up with reasons (“What if everybody did that?”) to help the kids develop independent moral judgment. The first sentence only proscribed a single act. The second invoked a universal principle that can be applied again and again. That’s influence at its best: Teach a man to fish, and all that.

My kids know — and are surely influenced by — my religious views. But I go to great lengths to counter that undue influence, keeping them off-balance while they’re young so they won’t be ossified before they can make up their adult minds:

“Dad? Did Jesus really come alive after he was dead?”

“I don’t think so. I think that’s just a made-up story so we feel better about death. But talk to Grandma Barbara. I know she thinks it really happened. And then you can make up your own mind and even change your mind back and forth about a hundred times if you want.”

That’s influence without indoctrination.

Indoctrination is another ball of cheese entirely. Princeton’s WordNet hits it right on the head, in my humble:

INDOCTRINATION (n.) Teaching someone to accept doctrines uncritically.

Here’s one of my own:

INDOCTRINATION (n.) The pre-chewing of someone else’s intellectual food.

“Because I/God/the Pope/Scripture said so” is the frame in which indoctrination is most often hung. Non-religious parents should be less likely to parent by indoctrination, if only because they’ve seen the iWord from the outside. Yet many fall into it anyway. Silly monkeys. Take a lesson from Sacha, who has recognized the iWord from inside religion.

At the heart of indoctrination is the distrust of reason. The indoctrinator simply can’t entrust so important a thing as [insert doctrine here] to the process of independent reasoning.

But freethought parenting should have confidence in reason at its foundation. We ought to know that either reason leads to our conclusions or our conclusions ain’t worth the neurons they’re written on. Teach kids to think independently and well, then trust them to do so. And part of that education is encouraging them to resist indoctrination of all kinds — even if it’s coming from Mom and Dad.

[N.B. Wikipedia also has a very thoughtful entry on indoctrination.]