The Most Elegant Two Measures in the History of Oh My Gawd (Bach ‘Air’)

- June 06, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

8 min

(#4 in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

If you gave me ten seconds to name the most gorgeously crafted, unsurpassably elegant masterpiece of musical art ever created in Western music, I would say, “Air from Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite in D, also known as ‘Air on the G String'” and ask what you’d like me to do with the other six seconds.

The list of reasons is long and wonky, but I’ll stop at two.

1. The Bass Line

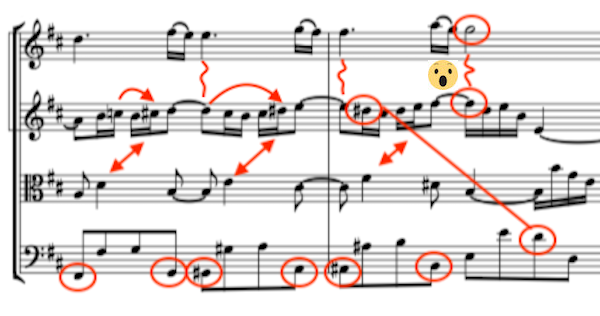

A bass line descending by step was common in the Baroque — part of something called the “doctrine of affections,” a way of signaling a particular emotion. Bach could have done something like this

or maybe an octave higher

Instead, he weaves elegantly between the octaves: down / up up / down down…

It’s such a graceful variation on a common idea. Follow the purple squares on the visualization for a few bars to see how it unfolds (15 sec):

2. The Most Elegant Two Measures in the History of Oh My Gawd

About halfway through is a two-bar passage that manages to somehow surpass everything that came before. The progression is not just chords but a smooth series of mini key changes — G major, A major, B minor, E minor. See all those sharps sprinkled in there as it rolls by? That’s Bach altering chords along the way to point to new keys, all hung on a bass line of rising half steps. The result is this rich tapestry of sound that builds tension with a dissonance on each downbeat, ending on that brief, searing G against F# in the violins. It’s an eight-beat master class in voice leading and harmony from the Lord High Commander of both.

Listen to those two measures (14 sec):

Now forget all that and enjoy the piece my wife and I chose as her wedding processional 27 years ago.

BACH, ‘Air’ from Third Orchestral Suite in D (5:00)

Hildegard’s Spooky, Dangerous Little Note

- June 05, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

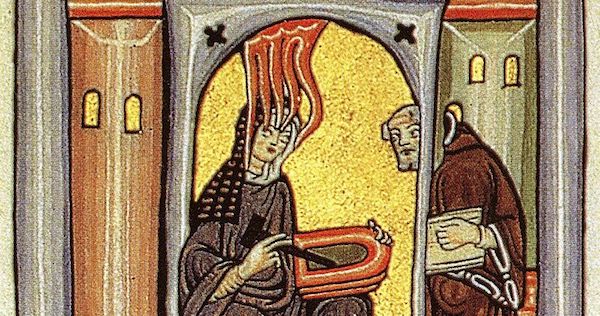

Usually these portraits of a composer passing on divinely-inspired music to a scribe featured Pope Gregory the Great (after whom Gregorian chant is misnamed). Having a woman in that chair shows the extraordinary place Hildegard occupied during her lifetime. From the Scivias manuscript (1151).

(#3 in the Laney’s List series — a music prof chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

Think of a revolutionary moment in music history. Beethoven’s 9th? The Rite of Spring? Schoenberg’s tone row? Piffle. The real revolution was the first time one pitch was sung at the same time as another — the first harmony.

There’s no way to know when that first happened, but we do know that early Jewish and Christian music was monophonic (one note at a time). The purity of a single tone was thought to be most appropriate for worship. Harmony introduces ratios of vibration, which introduces the dissonance spectrum, and Beelzebob’s your uncle.

Composers started easing into harmony in the 10th and 11th centuries, first putting simple drones under chant melodies, then doubling the chant melody at the fourth or fifth, then stretching the chant into long notes with florid melody above. Certain intervals were banned by the church, but by the 13th century all hell breaks loose, and the full chordal harmony of the Renaissance isn’t far behind.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was an abbess musician living and working in the middle of that revolution. Her music is often described as “otherworldly” or “mystical,” especially when she uses a drone and the Phrygian mode, which she does quite a bit. Phrygian is the same as a minor scale with one exception — the second note is only a half step above the tonic, so you get a lovely clash between them. Play a white-key scale on the piano starting on E and you’ll get a Phrygian scale. (Not if you’re pregnant, though: Pregnant women as far back as Golden Age Greece were not allowed to hear the Phrygian mode because the dissonant relationships between the pitches could summon demons.)

The drone in “O virtus” below is on the tonic and dominant (E and B), and the E Phrygian melody includes an F, which clashes yummily with that E drone as it passes by. You can hear that at 0:14, 0:36, and 0:52, etc. That delicious, spooky little Phrygian cloud passing over the harmony is Hildegard’s special sauce, the dangerous note that makes it otherworldly.

HILDEGARD, O virtus sapientiae (2:12)

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow me on Facebook:

And You Thought You Knew Scarlatti

- June 03, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

(#2 in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music. Back to #1)

If you made it to the second year of piano lessons, you probably know Domenico Scarlatti. After months of patiently listening to you lightly rowing and informing relatives about the demise of waterfowl, Mrs. Mawdsley told you in hushed tones that your hard work had paid off. You were ready at last for real music. You were ready for Scarlatti.

He wrote 555 keyboard sonatas, and some of them were simple and sedate enough for small, sticky fingers:

(16 sec)

But about 499 of his sonatas are entirely else.

Scarlatti spent most of his career writing brilliant, inventive, dynamic bursts of keyboard fireworks for the Spanish and Portuguese courts, and these Scarlatti sonatas probably never made it to your music stand. But after she bye-byed you out the door, poured herself a Bloody Mary and let down her messy piano teacher bun, it was this Scarlatti that Mrs. Mawdsley invited into her living room. This Scarlatti will blow your hair back. This Scarlatti is so much fun it hurts.

Watch the amazing Martha Argerich shred this one.

SCARLATTI Sonata in D Minor K 141

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Chopin and the Chopinuplets (Nocturne in B-Flat Minor)

- June 02, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

(First in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

The soundtrack of my childhood came through my brother’s piano in three threads: West Side Story, Scott Joplin, and Chopin. He played other things, but those are the ones I can still hear — and it’s Chopin that makes me feel five years old again. I would sometimes lie beneath the keyboard by the pedals with my back against the piano as he played nocturnes, picturing that tortured, tubercular Delacroix painting ^ on the cover of Ron’s music. Chopin is warm and dark and safe and sad to me, but it’s also the physical vibrations of that piano against my back.

All that to say: I don’t approach Chopin objectively.

The nocturne is meant to evoke the calm of night, and Chopin’s Nocturne in B-Flat Minor is no exception. But there are exceptions. When my son was four, he listened to a CD of Chopin nocturnes to go to sleep. That was fine until we left it running longer than usual and learned what Nocturne No. 13 does in the middle. Heh.

There’s a lot to talk about in the B-Flat Minor nocturne — including theorythings like the lowered sixth in major (0:29) and the spooky Neapolitan harmonies (1:11) that give Chopin his Chopiness — but I want to keep it short on these posts.

The thing I love most about this one is his liberation of the melody from the beat.

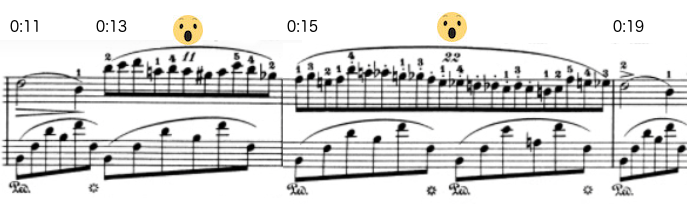

In the first bar, the right hand establishes that flow of eighth notes, six notes every half bar. The left hand dutifully takes over the flow, 1-2-3-4-5-6/1-2-3-4-5-6. Then at 0:13, as the left continues to churn out those sixes, the right hand suddenly gets naked and dances on the table:

Instead of six notes per half bar, the melody bursts into this effusive chromatic flow of 33 notes where 18 “should” be. Those Chopinuplets are saying screw your strict divisions, my soul is singing. A great interpreter (like Rubinstein below) frees that spirit even further by stretching the beats, allowing all those notes room to breathe. That’s Romanticism, and it happens again and again in the 20 nocturnes.

Now forget all that and enjoy.

CHOPIN, Nocturne in B-Flat Minor, op. 9 No. 1

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!