the legend of squishsquish

“Can I read you something from my Monster Museum book?”

I said sure, not knowing that we were launching a mini-obsession that so far has lasted a week. Delaney (6) flipped to the back of the book, which offers a short “bio” of each monster mentioned in the bad kiddie poetry that fills the rest of the book.

“‘BIGFOOT,’” she read. “‘Called Squishsquish in North America…’ Squishsquish?”

“Oh. Sasquatch.”

“You know about Bigfoot?” she asked, mighty impressed.

“A little,” I said. “Keep going. I want to hear.”

“‘Called Sasquatch in North America and Yeti in Asia. A huge, hairy, shy creature. Bigfoot prefers mountains, valleys, and cool weather. Many people claim to have seen and even photographed Squish…Squishkatch or Yeti or his footprints, but so far, no one has had a conversation with him.’ Haha! That’s funny.”

Each biographical entry has a little cartoon picture of the beast in question, with the exception of Bigfoot. We apparently know what a banshee looks like, and The Blob, and a poltergeist. But when it comes to Bigfoot, they simply put a question mark. I’m willing to bet it was the question mark that drew her attention to Bigfoot.

“If people took pictures,” she asked, “why is there a question mark?”

“I don’t know.”

“So is he real?”

“Some people think so, and some people think it’s a fake. Wanna see the pictures?”

We Googled up a few choice photos. Delaney gasped, launching into an enthralled monologue as I took furtive notes:

“It would be so interesting if Bigfoot was real. I really wonder if he is. It would be so cool if he was real! But maybe the picture is somebody in a gorilla suit. And maybe somebody went out with a big footprint maker and made footprints in the woods. Or maybe it’s real. But I’ll bet if he is real, he’s nice.”

“Why?”

“Because if he was mean, he’d be attacking people, and then we’d know he exists! But…there can’t be a person that big in a costume, so it seems like he has to be real somehow. Even the tallest person isn’t that tall.”

“So do you think it’s probably real, or probably not?”

She paused and thunk. “I’m not sure. I’m really, really not sure. I’ll bet scientists are trying to figure out. It’s just so cool to think about. It makes you curious.”

Yesterday she had a friend over—the pseudonymous Kaylee of a long-ago post—and dove right into the quest as I quietly transcribed the conversation on my laptop:

DELANEY: Have you ever heard of Bigfoot?

KAYLEE: No. What’s Bigfoot?

D: You have got to see this. You have got to see this. [Types BIGFOOT into Google.] Look, there it is. It’s called Bigfoot, but some people say Squishsquish.

K: What is it?!

D, with didactic precision: Some people say it’s like a gorilla man who lives in the forest. But you don’t have to worry. He wouldn’t be in any forest near us. Some people think it’s not even real.

K: So that’s Bigfoot??

D: Well it’s a picture.

K: So Bigfoot is real!

D: Nope, we don’t know that for sure. (Reads from website.) “An appeal to protect Bigfoot as an in-danger species has also been made to the U.S. Congress.”

K, (reading ahead): Look, it says right here, “Bigfoot is not real.” So he’s not real.

D: But we don’t know for sure. That’s just what the person says who has that website. That doesn’t make it for sure.

[Laney switches to image search, pulling up a full page of yetis.]

K: I hope it isn’t real. That would be so scary.

D: I hope it is. It would be so cool!

K: (looking at one photo): Does he only live in snow?

D: No look, there are pictures with no snow. It seems like he would hibernate. I wonder what he would eat.

K: Probably people.

D: I just wonder everything about him. Doesn’t it just make you so curious?

K: No. It makes me freaky.

I have a favorite particular moment in that dialogue–I’ll let you guess. But my favorite thing overall is Laney’s Saganistic approach to knowledge. Just as Carl Sagan wanted more than anything for intelligent life to exist elsewhere in the universe, Laney really wants Bigfoot to be real. It would, in both cases, be “so cool.” But that has no effect on her belief, or his, that the beloved possibility is real. Neither can see much joy or point in pretending that a wish makes it so. Both are happy to wait for the much greater thrill of knowledge, of the discovery that something wonderful turns out to be not just cool, but true.

On waking the heck up

To be awake is to be alive. I have never met a man who was quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?

From Walden by Henry David Thoreau

I was interviewed Tuesday for the satellite radio program “About Our Kids,” a production of Doctor Radio and the NYU Child Study Center, on the topic of Children and Spirituality. Also on the program was the editor of Beliefnet, whom I irritated only once that I could tell. Heh.

“Spirituality” has wildly different meanings to different people. When a Christian friend asked several years ago how we achieved spirituality in our home without religion, I asked if she would first define the term as she understood it.

“Well…spirituality,” she said. “You know—having a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and accepting him into your life as Lord and Savior.”

Erp. Yes, doing that without religion would be a neat trick.

So when the interviewer asked me if children need spirituality, I said sure, but offered a more helpful definition—one that doesn’t exclude 91 percent of the people who have ever lived. Spirituality is about being awake. It’s the attempt to transcend the mundane, sleepwalking experience of life we all fall into, to tap into the wonder of being a conscious and grateful thing in the midst of an astonishing universe. It doesn’t require religion. Religion can, in fact, and often does, blunt our awareness by substituting false (and dare I say inferior) wonders for real ones. It’s a fine joke on ourselves that most of what we call spirituality is actually about putting ourselves to sleep.

For maximum clarity, instead of “spiritual but not religious,” those so inclined could say “not religious–just awake.”

I didn’t say all that on the program, of course. That’s just between you, me, and the Internet. But I did offer as an example my children’s fascination with personal improbability – thinking about the billions of things that had to go just so for them to exist – and contrasted it with predestinationism, the idea that God works it all out for us, something most orthodox traditions embrace in one way or another. Personal improbability has transported my kids out of the everyday more than anything else so far.

Evolution is another. Taking a walk in woods over which you have been granted dominion is one kind of spirituality, I guess. But I find walking among squirrels, mosses, and redwoods that are my literal relatives to be a bit more foundation-rattling.

Another world-shaker is mortality itself, about which another small series soon. Mortality is often presented as a problem for the nonreligious, but in terms of rocking my world, it’s more of a solution. Spirituality is about transforming your perspective, transcending the everyday, right? One of my most profound ongoing “spiritual” influences is the lifelong contemplation of my life’s limits, the fact that it won’t go on forever. That fact grabs me by the collar and lifts me out of traffic more effectively than any religious idea I’ve ever heard. A different spiritual meat, to be sure, but no less powerful.

The program will air Friday August 8, 8-10am Eastern Time (US) on SIRIUS Satellite Channel 114—or listen online at Doctor Radio.

[BONUS QUESTION: Did you yawn when you saw the baby?]

hopeful music

Last night a memory bobbed to the surface of Delaney’s brain — something I’d said in passing a good two years ago when she was four.

|

“Remember that music that’s been playing for my whole life?” she asked at bedtime. “I wonder if it’s still playing.”

“Huh? Oh…that! Yes, it is!” I retold the story, thrilled that she finds it as cool as I do:

“There was a composer who lived a long life and died not too long ago. His name was John Cage. His music wasn’t like anyone else’s because he didn’t just want to entertain people. He wanted them to think and wonder and even laugh. Mostly he wanted them to think about music in a new way.

“He wrote one piece I especially like. Wanna hear it?”

“Sure.”

I sat in silence for thirty seconds. “Okay, that was it. Well, just part of it.”

She looked puzzled. “Just…being quiet?”

“Well…was it really quiet?” I asked.

“No! I heard Max [the guinea pig] making little noises. And the ceiling fan going whoosh whoosh.”

“That’s the idea. This composer wanted us to hear all the sounds around us and to think of it as music that’s playing all the time. So he wrote a piece of silence to make us hear all the stuff we usually ignore.”

“That’s so cool.”

Many of you will have heard of this piece, which is called 4’33” and consists of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. It can be performed, Cage said, on any instrument or combination of instruments and in any number of movements. But that’s not the piece she was asking about. “And he wrote another piece for organ called ‘As Slow as Possible.'”

“That’s the one!”

“And then some people decided to play it really slow — so slow it would last for 639 years. They found a little church in the middle of Germany that wasn’t used anymore, and they built a special organ just to play this one piece of music.

“It started playing seven years ago on September 5th, 2001. But the music starts with a rest — a silence in music — so the first thing you heard was nothing! For seventeen months!”

“Haha! Weird!”

“And right in the middle of that silence — you were born.”

“Awesome,” she whispered.

She was right. Somehow, juxtaposing her birth and that silence was awesome. Even better: The bellows sprung to life on that day in September, and pumped away for twenty months as the only sound in the church. Once again, music without music.

“Then one day in the middle of the winter, when you were one and a half, the first notes started to play. Hundreds of people gathered in the little church to hear the notes start. Most of the time, though, the notes are playing with no one there. Little weights hold down the keys. Then every two years or so, it’s time for the notes to change again, and people come from around the world to hear it.”

|

“And it’s still playing right now?”

“Yep, it’s playing right now. And here’s the thing: It will be playing on the moment you graduate from high school and when you graduate from college. It will be playing when you get your first job, when you get married, and when your kids are born.

“The music that started the year you were born will still be playing at the end of your life. It will be playing when your grandchildren are born and when they die, and their grandchildren, and their grandchildren, and on and on, for 639 years.”

“Awesome!”

“Just think how different the world will be then.”

“I wonder if they will be different creatures from us then [one of her favorite ponders]. Like we used to be different animals a long time ago.”

“Fun to think about, eh?” I kissed her on the head and she drifted off.

The Cage project will strike some people as bizarre or silly. There was a time it would have hit me that way, back when I thought 20th century art and music was one big con game. But the more I think about the slowest piece of all time, the more it moves me.

The church is in Halberstadt, Germany. Suppose someone had started playing a piece of music in Halberstadt 639 years ago, in 1369. The Ming dynasty in China was one year old. Europe continued to reel in disorder one generation after the Black Death. The music would have ushered in the dawning of the Renaissance, the voyages and outrages of the New World explorers, and the scientific and artistic revolutions of the 16th century.

Luther’s Reformation and the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries would have raged around it. It would have been playing as the town itself changed hands from Prussia to Napoleon’s Westphalia and back to Prussia before becoming part of Saxony, then Germany, playing as Allied bombs fell in 1945, as the town was closed into communist East Germany and as it was returned to the heart of reunified Germany.

Would that piece have found its way to the last barline?

Starting a piece of music implies an intention to finish it. So starting a 639-year piece is, among other things, an extraordinary statement of human hope. it implies that we may still be here in 639 years, and that the intervening generations, with all their own changing concerns and values and ordeals, will nonetheless pick up the baton and run with the project we have begun. It is, in other words, a perfect metaphor for human life itself.

The aesthetics of the piece, as with so much of the music of Cage, are immaterial. It’s the idea that moves me. To hear the chord currently being played is to connect yourself to the recent past and the distant future in a way never before quite possible. That’s part of the reason that every time the chord changes, hundreds of people come from around the world to hear it happen.

The last chord change was in May of 2006, the month I resigned my college professorship. The next change is this Saturday, July 5, 2008.

Thanks to the hopeful gesture of even beginning such a thing, I can picture it finishing. So long as we can keep from killing each other, cooking the planet, or blowing up Halberstadt with technologies still undreamt — and if Jesus can hold off a little longer on his glorious return — then maybe, just maybe, our optimism will have been justified.

the giddy geek

- June 11, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In Science, wonder

16

16

We live in a universe made of a curved fabric woven of space and time in which hydrogen, given the proper conditions, eventually evolves into Yo Yo Ma. — from Parenting Beyond Belief

Last year I wrote about Major Tom and the way the Apollo program lit up my imagination and fueled my wonder in the 70s. I always shook my head in pity at anyone who shook his head in pity at the “coldness” and “sterility” of the scientific worldview.

I touched on this in one of my essays in Parenting Beyond Belief called “Teaching Kids to Yawn at Counterfeit Wonder”:

Religious wonder—the wonder we’re said to be missing out on—is counterfeit wonder. As each complex and awe-inspiring explanation of reality takes the place of “God did it,” the flush of real awe quickly overwhelms the memory of whatever it was we considered so wondrous in religious mythology. Most of the truly wonder-inducing aspects of our existence—the true size and age of the universe, the relatedness of all life, microscopic worlds, and more—are not, to paraphrase Hamlet, even dreamt of in our religions. Our new maturity brings with it some real challenges, of course, but it also brings astonishing wonder beyond the imaginings of our infancy.

I offered a short list of the kinds of scientific revelations that make me woozy with awe:

If you condense the history of the universe to a single year, humans would appear on December 31st at 10:30 pm. That means 99.98 percent of the history of the universe happened before humans even existed.

Look at a gold ring. As the core collapsed in a dying star, a gravity wave collapsed inward with it. As it did so, it slammed into the thundering sound wave heading out of the collapse. In that moment, as a star died, the gold in that ring was formed.

We are star material that knows it exists.

Our planet is spinning at 900 miles an hour beneath our feet while coursing through space at 68,400 miles per hour.

The continents are moving under our feet at 3 to 6 inches a year. But a snail’s pace for a million millennia has been enough to remake the face of the world several times over, build the Himalayas and create the oceans.

Through the wonder of DNA, you are literally half your mom and half your dad.

A complete blueprint to build you exists in each and every cell of your body.

The faster you go, the slower time moves.

Your memories, your knowledge, even your identity and sense of self exist entirely in the form of a constantly recomposed electrochemical symphony playing in your head.

All life on Earth is directly related by descent. You are a cousin not just of apes, but of the sequoia and the amoeba, of mosses and butterflies and blue whales.

Now that, my friends, is wonder.

I’ve tried to pay attention when geeks (a term of genuine endearment from me) of one stripe or another are enraptured at the poetry or wonder of something I can’t see. I know they are experiencing something transcendent, something that I lack the language or knowledge to apprehend directly.

I remember a student of mine, a math major/violist, walking into a rehearsal with a look of utter bliss, as if drunk on a mantra.

“What on Earth happened to you?” I asked.

“Laplace transforms,” she said. “Laplace transforms happened to me. They are so beautiful I can hardly stand it.”

I knew she was right, and that I would never know why. I was envious.

So imagine the fellow-feeling I felt when I saw this wonderful video by Phil Plait at Bad Astronomy. Next time someone starts into the drone about the cold, passionless world of science, show them this:

The awe-inspiring picture isn’t even my main point — it’s what the picture has done to Phil, someone who knows what it means, and better still, takes the time to share his amazement with the rest of us. Thanks, Phil!

[Thanks to Tim Mills at Friendly Humanist for leading me to this video.]

can death give birth to wonder? (revised)

[NOTE: In preparing the following blog entry, I fell prey to a classic critical thinking error that goes by several names: “selective reporting,” “confirmation bias,” and “being an idiot.” Though the first several paragraphs are impeccably sound, the section on the Woodward paper is, unfortunately, complete rubbish. I say ‘unfortunately’ because it would have been fascinating if true. Ahh, but that’s how we monkeys always step in it, isn’t it now? I’ll leave the post up as a monument to my shortcomings and prepare another post about the specific way in which I misled myself.]

_______________

You’ve probably seen the studies confirming the low frequency of religious belief among scientists, and the fact that the most eminent scientists are the least likely to believe in a personal God. Very interesting, and not surprising. Uncertainty would have been profoundly maladaptive for most of our species history. The religious impulse is an understandable response to the human need to know, or at least to feel that you do. Once you find a (much) better way to achieve confidence in your conclusions, one of the main incentives for religiosity loses its appeal.

Psychologist James Leuba was apparently the first to ask scientists the belief question in a controlled context. In 1914, Leuba surveyed 1,000 randomly-selected scientists and found that 58 percent expressed disbelief in the existence of God. Among the 400 “greater” scientists in his sample, the figure was around 70 percent.1 Leuba repeated his survey in 1934 and found that the percentages had increased, with 67 percent of scientists overall and 85 percent of the “eminent” group expressing religious disbelief.2

The Larson and Witham study of 1998 returned to the “eminent” group, surveying members of the National Academy of Sciences and finding religious disbelief at 93 percent. All sorts of interesting stats within that study: NAS mathematicians are the most likely to believe (about 15 percent), while biologists were least likely (5.5 percent).

[Here’s where the nonsense begins. Avert your eyes.]

But I recently came across a related statistic about scientists that, given my own background, ranks as the single most thought-provoking stat I have ever seen.

As I’ve mentioned before, my dad died when I was thirteen. It was, and continues to be, the defining event in my life, the beginning of my deepest and most honest thinking about the world and my place in it. My grief was instantly matched by a profound sense of wonder and a consuming curiosity. It was the start of the intensive wondering and questioning that led me (among other things) to reject religious answers on the way to real ones.

Now I learn that the loss of a parent shows a robust correlation to an interest in science. [Not.] A study by behavioral scientist William Woodward was published in the July 1974 issue of Science Studies. The title, “Scientific Genius and Loss of a Parent,” hints at the statistic that caught my attention. About 5 percent of Americans lose a parent before the age of 18. Among eminent scientists, however, that number is higher. Much higher.

According to the study, 39.6 percent of top scientists experienced the death of a parent while growing up—eight times the average.

Let’s hope my kids can achieve the same thirst for knowledge some other way.

Many parents see the contemplation of death as a singular horror, something from which their children should be protected. If nothing else, this statistic suggests that an early encounter with the most profound fact of our existence can inspire a revolution in thought, a whole new orientation to the world — and perhaps a completely different path through it.

[More later.]

_____________________

1 Leuba, J. H. The Belief in God and Immortality: A Psychological, Anthropological and Statistical Study (Sherman, French & Co., Boston, 1916).

2 Leuba, J. H. Harper’s Magazine 169, 291-300 (1934).

3Larson, E. J. & Witham, L. Nature 386, 435-436 (1997).

4Woodward, William R. Scientific Genius and Loss of a Parent, in Science Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3 (Jul., 1974), pp. 265-277.

wondrous strange

- March 17, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, Parenting, Science, wonder

3

3

The only solid piece of scientific truth about which I feel totally confident is that we are profoundly ignorant about nature… It is this sudden confrontation with the depth and scope of ignorance that represents the most significant contribution of twentieth-century science to the human intellect.

Lewis Thomas

Connor (12) was studying for a science quiz on cells, muttering about eukaryotes and pseudopods and such, like it was the driest of all possible subjects. Life…*yawn*

I was working on a way to liven it up for him when I realized, to my amazement, that I had never shared with him (or with you, as far as I remember) one of my favorite science videos. It’s an award-winning computer animation of the internal workings of a single white blood cell, animated by the good folks at Xvivo:

Connor lit up like a, like a…like a seventh grader who suddenly found his homework interesting.

Well…more interesting, anyway.

_________________________

[N.B. Great book with the same effect: Lewis Thomas, Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher]

strange maps

- December 07, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, Parenting, reviews, wonder

7

7

Please cancel my appointments for the rest of the month, take the phone off the hook, and don’t expect another blog entry until spring. I have found the website of my dreams and am going to live there for awhile. Someone please pay my rent, feed my children and satisfy my wife until I return.

Maps absorb me like a…what’s something really absorbent…like a sponge-like thing. In England I pored over the incredible Ordnance Survey maps for hours at a time.

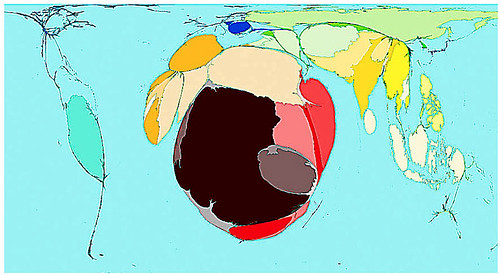

I’ve always particularly loved the paradigm rattlers, like this

which makes the point that a Northerly orientation is arbitrary, having been selected, by the most astonishing coincidence, by Northern Hemisphereans, who apparently like it on top.

I was 18 when I first saw Joel Garreau’s “Nine Nations of North America” concept, from the book of the same name:

Now I’ve found a blog called STRANGE MAPS, and I have no further need of the outside world. In addition to the above, there are maps to compare the relative wealth of nations today

and comparisons throughout time:

Deaths in war since 1945:

There is a map of US states renamed for countries with similar GDPs:

how the world would be if all the land were water and all the water land:

and what it’ll look like in 250 million years:

…all with intelligent commentary and links. I’ve only scratched the surface. There’s Europe if the Nazis had won. A map of the United States from the Japanese point of view. A map of the U.S. with the former territories of Indian nations overlaid. World transit systems drawn as a global world transit map in the style of the London Underground. A color-coded map of blondeness in Europe and of kissing habits in France.

Plop a child of a certain type and age (about 10-16) in front of Strange Maps (or another called Worldmapper, where the resized world maps originate) and don’t expect a response when you call ’em for dinner. I can’t wait for my boy to get home.

the unconditional love of reality

…CONNOR AT THE WORLD OF COKE (…after the Tasting Room)

A Christian friend once asked me what it is about religion that most irritates me. It was big of her to ask, and I did my best to answer. I said something about religion so often actively standing in the way of things that are important to me — knowledge of human origins, for example, important medical advances, effective contraception, women’s rights…the simple ability to think without fear. I gave a pragmatic answer — and the wrong one.

Not that those things aren’t important. They’re all crowded up near the top of my list of motivators. But in the years since I gave that answer, I’ve realized there’s something much deeper, much more fundamentally galling and outrageous that religion too often represents for me — something that constitutes one of the main reasons I hope my kids remain unseduced by any brand of theism that endorses it.

What I want them to reject, most of all, is the conditional love of reality.

I’ve talked to countless Christians about their religious faith over the years. I have often been moved and challenged by what their expressed faith has done for them. But the doctrine of conditional love of reality simply mystifies, offends, and frankly infuriates me.

Conditional love is at play whenever a healthy, well-fed, well-educated person looks me in the eye and says, Without God, life would be hopeless, pointless, devoid of meaning and beauty. Conditional love is present whenever a believer expresses “sadness” for me or my kids, or wonders how on Earth any given nonbeliever drags herself through the bothersome task of existing.

Whenever I hear someone say, “I am happy because…” or “Life is only bearable if…”, I want to take a white riding glove, strike them across the face, and challenge them to a duel in the name of reality.

The universe is an astonishing, thrilling place to be. There’s no adequate way to express the good fortune of being conscious, even for a brief moment, in the midst of it. My amazement at the universe and gratitude for being awake in it is unconditional. I’m thrilled if there is a god, and I’m thrilled if there isn’t.

Unconscious nonexistence is our natural condition. Through most of the history of the universe, that’s where we’ll be. THIS is the freak moment, right now, the moment you’d remember for the next several billion years — if you could. You’re a bunch of very lucky stuff, and so am I. That we each get to live at all is so mind-blowingly improbable that we should never stop laughing and dancing and singing about it.

Richard Dawkins expressed this gorgeously in my favorite passage from my favorite of his books, Unweaving the Rainbow:

After sleeping through a hundred million centuries, we have finally opened our eyes on a sumptuous planet, sparkling with color, bountiful with life. Within decades we must close our eyes again. Isn’t it a noble, an enlightened way of spending our brief time in the sun, to work at understanding the universe and how we have come to wake up in it? This is how I answer when I am asked—as I am surprisingly often—why I bother to get up in the mornings.

I want my kids to feel that same unconditional love of being alive, conscious, and wondering. Like the passionate love of anything, an unconditional love of reality breeds a voracious hunger to experience it directly, to embrace it, whatever form it may take. Children with that exciting combination of love and hunger will not stand for anything that gets in the way of that clarity. If religious ideas seem to illuminate reality, kids with that combination will embrace those ideas. If instead such ideas seem to obscure reality, kids with that love and hunger will bat the damn things aside.

And when people ask, as they often do, whether I will be “okay with it” if my kids eventually choose a religious identity, my glib answer is “99 and three-quarters percent guaranteed!” That unlikely 1/4 percent covers the scenario in which they come home from college one day with the news that they’ve embraced a worldview that says they are wretched sinners in need of continual forgiveness, that hatred pleases God, that reason is the tool of Satan, and/or that life without X is an intolerable drag — and that they’d be raising my grandkids to see the world through the same hateful, fearful lens.

Woohoo! is not, I’m afraid, quite a manageable response for me in that scenario. Yes, it would be their decision, yes, I would still love their socks off — and no, I wouldn’t be “okay with it.” More than anything, I’d weep for the loss of their unconditional joie de vivre.

But since we’re raising them to be thoughtful, ethical, and unconditionally smitten with their own conscious existence, I’ll bet you a dollar that whatever worldview they ultimately align themselves with — religious or otherwise — will be a thoughtful, ethical, and unconditionally joyful one. Check back with me in 20 years, and for the fastest possible service, please form a line on the left and have your dollars ready.

deep family

- October 16, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In Parenting, Science, wonder

2

2

Deena at The Descent of Mills wrote an *exquisite* and wonder-inducing post very (very!) shortly after bringing her daughter Kaia into the world. Those unfortunates out there who find a scientifically-informed worldview ‘cold’ or ‘reductionist’ or ‘blah blah blah,’ be forewarned: this is your worst nightmare. As for the rest of us, prepare for a real privilege:

Introducing Kaia Elizabeth Mills, latest in a long line of carbon-based lifeforms. Kaia traces her ancestry back to an unnamed protoplasmic replicator which lived about four billion years ago. Since inventing sex about 2.5 billion years ago, every member of Kaia’s clan has had not one but two burstingly proud parents.

Among that replicator’s descendants, most remain single-celled. Kaia’s ancestors learned cooperation and have been massively multi-cellular for countless generations. When born, Kaia herself contained 8lb 6oz (3800g) of microscopic cells and was 55.5 cm (22 inches) in length.

One of several branches of the family who have (independently) developed sight, Kaia gazes at the world through deep blue eyes.

Thanks to a relatively recent family development (mammals, 247 million years ago), Kaia spent the first nine months of her development as part of her mother’s body, and so the family have opted to celebrate the moment of her emergence from that body as her “Birth Day” – six minutes past noon on the 28th of September 2007.

Though Kaia’s family are a relatively hairless part of the ape clan, she was born with her hominid cephalus covered in rich dark hair.

(My mind immediately went to my Aunt Marilyn who seriously blew a fuse when my mother, upon the birth of my little brother, said, “He looks like a little monkey!” Marilyn would be spinning in her grave at Deena’s post, if she weren’t still alive.)

I can’t help picturing that Deena is writing from the middle-distant future, from a time when we’ve suddenly awakened to the inspiration all around us and stopped insisting that Story X or Fable Y must be true for life to be endured. The wonder of the real world is such that we’ll never be able to adequately grasp and express it. But ohhh, how fun it is to try!

Kaia’s dad, by the way, is Friendly Humanist Tim Mills. Read Deena’s complete post here, with pix!

[For the origin and meaning of Kaia’s lovely name, visit this page. While you’re there, enjoy the Y-axis on the frequency chart provided, which must surely mean something.]

for your viewing pleasure

CONNOR ATOP BRAILES HILL, OXFORDSHIRE, OCTOBER 2004

Two new feature pages have been added here at The Meming of Life:

1. TEN WONDERFULL THINGS

I’ve grappled with the problem of how best to present links of interest. Blogrolls are fine, but short ones are incomplete and long ones make my eyes cross.

My solution is TEN WONDERFULL THINGS, an ever-evolving list of links to (always only) ten wonder-full things that relate in some way to the topics explored in the Meming of Life: parenting, the secular life, wonder, fun, sex, death, questions, kids, philosophy, humor, Atlanta, science, England, books, monkeys…things like that. No particular order. Visit often as the list slowly morphs.

2. I’M *SO* GLAD YOU ASKED

Wondering and questioning are the heart and soul of secular parenting. I’M *SO* GLAD YOU ASKED is a blog within a blog listing some of the questions and hypotheses my kids — Connor (now 12), Erin (now 9), and Delaney (now 5) — have come out with over the years. Though this page is primarily a personal family record, I’ve obviously invited visitors in, so I’ll try not to include the kind of cutesy-wootsey questions only a parent could love. I’m including it in the blogworks here because the questioning environment we build for our children is among the most important influences on their intellectual development. I’m endlessly fascinated by these questions and always thinking about how best to encourage them.

So no, in case the title led you to believe this was an FAQ, it is not. These Q’s are not frequently asked. Each tends to appear only once, giving us just that one chance to get it right, one chance to react in a way that nurtures and encourages the next question, and the next.

These are not dimly-remembered paraphrases. Each was written down within three minutes of being said. My hope in creating this page is to capture just a little of the electric thrill I get from being the father of three bighearted and curious kids who’ve never heard of such a thing as an unaskable question.

Click on the links in the upper left of the blog’s home page.