Words fail me

Love is too weak a word for what I feel – I luuurve you, you know, I loave you, I luff you.

WOODY ALLEN in Annie Hall

I was born in the Sixties. My first two kids were born in the Nineties. But try to name the decade my youngest was born in, the one we’re in at the moment, and you’re left muttering clunkers like “the first decade of the twenty-first century,” or sounding like Grandpa Simpson by referring to the “aughts.” It’s called a lexical gap, a concept for which a given language lacks a concise label. German is said to lack a precise word for a person’s “chest,” while English speakers are left speechless when it comes to Fahrvergnügen.

When I first heard Alvy Singer struggling to express his feelings for Annie Hall, I thought it was just for laughs. But I’ve begun to struggle in recent years with precisely the same lexical gap — so much so that I’ve almost entirely stopped telling my wife and children that I love them.

Let me explain. No, there is too much. Let me sum up.

The problem is the overuse of what was once, I suspect, a more sparingly-used, and therefore more powerful, word. The fact that Paul McCartney’s only response to the problem of “silly love songs” was to sing the phrase “I love you” fifteen times in three minutes seems to prove my point.

As a result of using “love” to express our feelings about everything from self-indulgence (“I love sleeping in on Sunday”) to food (“I love Taco Bell’s new Pizzaburgerrito”), I find the word “love” now entirely inadequate to describe the feeling engendered in me by my wife and kids. I don’t love them. I luuurve them.

No no, come back. I’m not going to wax rhapsodic. I’m zeroing in on a practical, lexical problem, that’s all.

Mawwiage

Mawwiage. Mawwiage is what bwings us togevah today. Mawwiage, that bwessed awwangement, that dweam wifin a dweam. And wuv, twu wuv, wiw fowwow you, fowevah.

IMPRESSIVE CLERGYMAN from The Princess Bride

Whenever I think of the reasons I luuurve my wife, I recall an event I attended two years ago — a debate between an atheist and a theist. I described the scene in PBB (pp. 96-7):

When the discussion turned to morality, [the theist] said something I will never forget. “We need divine commandments to distinguish between right and wrong,” he said. “If not for the seventh commandment…” He pointed to his wife in the front row. “…there would be nothing keeping me from walking out the door every night and cheating on my wife!”

His wife, to my shock, nodded in agreement. The room full of evangelical teens nodded, wide-eyed at the thin scriptural thread that keeps us from falling into the abyss.

I sat dumbfounded. Nothing keeps him from cheating on his wife but the seventh commandment? Really?

Not love?

How about respect? I thought. And the promise you made when you married her? And the fact that doing to her what you wouldn’t want done to you is wrong in every moral system on Earth? Or the possibility that you simply find your marriage satisfying and don’t need to fling yourself at your secretary? Are respect and love and integrity and fulfillment really so inadequate that you need to have it specifically prohibited in stone?

I first dated Becca because of conditional things. Non-transcendent things. Had she not been so unbearably attractive to me, had she not had the most appealing personality of anyone I knew, had she not been so funny and smart and levelheaded, I wouldn’t have flipped over her like I did. It may sound off to say it this way, but she fulfilled the conditions for the relationship I wanted, and I, thank Vishnu, did the same for her. I asked her to marry me in large part because of these not inconsiderable things.

But then, the moment I asked her to marry me, something considerably more transcendent began to happen between us. She said yes — and I was instantly struck dumb by the power of it. This splendid person was willing to commit herself to me for the remainder of her one and only life.

Holy (though I try to keep this blog free of both these words) shit.

No, I am not waxing, dammit, I am making a point. We were moving into the unconditional, you see. She had moved from being one of the many attractive, magnetic, funny, smart people I knew to The One Such Person Who Committed to Me. See the difference? And then, once she actually took three small packets of my DNA and used them to knit children — well, at that point, it became hard to look at her without bursting into song. I’m still not over it. What was a strong but technically conditional love moved decisively into unconditional luuurve.

So yes, there are things beyond the seventh commandment that keep me from cheating on my wife. Like the hilarity I feel at the thought of finding any other woman with any amount of those conditionals more attractive.

As for the children…

You’re an atheist? So then…you think your children are…just a bunch of…processes?

JEHOVAH’S WITNESS at my door last year

Last week a radio interviewer asked about my kids, with mild facetiousness: “So how about your own kids? Good kids, ya love ’em and everything?” In addition to the pure silliness of answering such a question, I fell head-first into that lexical gap once again — and the resulting three seconds of dead air probably did me no favors with the audience. I finally sputtered something about them being amazing kids, terrific kids, but it fell short, as it always does, of my real feelings.

I don’t make up for this lexical gap with the kids by telling them I luuurve them. Instead, almost every single day, I tell them, “I do not love you.” And they smile and say, “Oh yes you do!” — and all is understood.

They know in a thousand ways that I am transported by being their dad. They’ve become accustomed, for example, to the sudden realization that Dad is staring again. They’ll get that prickly feeling and turn to see me lost in a contemplative gawk. They’re very good about it, usually returning a smile rather than a roll of the eyes, which I think is very nice of them.

Recognizing that the love of our children is rooted in part in biology — that I am, in part, adaptively fond of them — does not in the least diminish the way I’m transported by contemplating the fact of them, and of our special connection, and of their uniqueness, of the generational passing of the torch.

But it’s interesting to note that, unlike my relationship with Becca, this meditative gawking began on day one. The order of things is reversed. My marriage started in the conditional and added the unconditional. I loved her from the beginning, but only slowly came to be so completely slain by her.

Kids, on the other hand, begin in the unconditional and add the conditional. From the moment they emerged from my wife — seriously, reflect on that for a moment — they were unconditionally wonderful to me. They were half me and half she. They were our connection to the future. Etc.

Gradually we formed additional bonds based on their actual attributes. They are smart as whips, wickedly funny, generous and kind and fun to be around. But that’s all frosting on an unconditional cake. Marriage, on the other hand — if it goes well — starts with frosting and gradually slips the cake underneath.

So yes, my kids are “processes,” whatever that means, and so is my wife. But they are also the main reasons I wake up grateful and filled with meaning and purpose every single day.

(Wax off.)

far above the world

- September 16, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In death, My kids, Parenting, Science, wonder

23

23

I’m on about bedtime again— but this time it’s the soundtrack.

My mother sung me to sleep for most of my childhood, and I love her for it. In hopes that my own children will profess love for me in their eventual blogs, I sing to them every night as well. And for no other reason.

At an average of two songs per child per night, that’s nearly 20,000 songs so far. Easily bored as I am, the repertoire doesn’t stand still for long: Stardust, Yesterday, Danny Boy, Kentucky Babe, Long and Winding Road, Witchdoctor, Cat’s Cradle, Unchained Melody, Stand By Me, Blackbird, Michelle, The Christmas Song, Lady in Red (not that one), Imagine, Close to You, Mean Mister Mustard, Everything’s All Right (from Superstar, with Judas’ angry outburst included), Happy Together, The Galaxy Song, Our Love is Here to Stay…you know, stuff like that.

A few nights ago, an old friend floated into my head, unbidden—and I began to sing a song that once reached further into my imagination than perhaps any other before or since:

Ground Control to Major Tom…

Ground Control to Major Tom…

Take your protein pills and put your helmet on…

“What…in…the…world?!” Erin’s head was off the pillow. I could feel the puzzled glare cutting through the dark.

(“10”) Ground Control (“9”) to Major Tom (“8”)…(“7”)

(“6”) Commencing countdown, engines on…(“3”)

(“2”) Check ignition, and may God’s love be with you…

“This is weird,” said Delaney.

“This is TOTALLY weird,” said Erin, leaning forward on her elbow.

“This is…”

THIS IS GROUND CONTROL TO MAJOR TOM

YOU’VE REALLY MADE THE GRADE

AND THE PAPERS WANT TO KNOW WHOSE SHIRTS YOU WEAR

NOW IT’S TIME TO LEAVE THE CAPSULE IF YOU DARE

I was only slightly older than Delaney when Neil Armstrong celebrated my wedding anniversary by landing on the moon 22 years in advance, to the day. It was the same year David Bowie gave us Major Tom. I watched the moon landing with my parents, who tried very hard to impress the significance on me. I was a complete NASAholic by age eight.

As I built model after model of the lunar module and command module and watched telecasts of one Apollo crew after another in grainy black-and-white, I recall being both awed and miffed at the astronauts—awed because I wanted so much to be in their boots, and miffed because they were all business. Houston this and Houston that. Engaging the forward boosters, Houston. Switching on the doohickey, Houston. Even in elementary school, it occurred to me that there should be a little more evidence of personal transformation. I wanted to hear them say Ooooooooooooo, in a fully uncrewcutted, unprofessional way. Holy cow, I wanted. I’m in outer space.

Eventually we got golfing on the moon and some zero-G hijinks. That’s fine. But that’s not transformation. I wanted evidence that they were moved by their experience, that they would never be the same after seeing Earth from space. They wrote about it years later when I was in college, but it was in high school that a Bowie song I’d never heard before finally said what I’d waited to hear. Take it, Major Tom:

Here am I sitting in a tin can

Far above the world

Planet Earth is blue, and there’s nothing I can doThough I’m past 100,000 miles

I’m feeling very still

And I think my spaceship knows which way to go

Tell my wife I love her very much, she knows.

For three days now we’ve listened to Bowie’s version rather than my own at bedtime, complete with those epic Mellotron strings, and debated what exactly happens in those final stanzas. The girls demand to know: Is he okay? What happened? Does he come back?

Ground Control to Major Tom

Your circuit’s dead, there’s something wrong

Can you hear me Major Tom?

Can you hear me Major Tom?

Can you hear me Major Tom?

Can youHere am I floating ’round my tin can,

Far above the Moon,

Planet Earth is blue

And there’s nothing I can do.

“Omigosh,” said Connor after one hearing. “He killed himself.”

“No he did not!” I was indignant, partly because it had never occurred to me.

“Yes he did. ‘Tell my wife I love her very much’—and then his circuit goes dead? Come on, Dad.”

I’d heard the song a thousand times. Yes, I thought he might not have made it, but it never once occurred to me that he’d done himself in. Huh.

It makes sense. He was moved, all right. He was so transformed by the experience that he liberated himself from Ground Control, unhooked his tether, and went careening, blissfully, beyond the moon.

Okay then. Be careful what you wish for.

the total perspective vortex

- September 10, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, Parenting, Science, wonder

0

0

In an infinite universe, the one thing sentient life cannot afford to have is a sense of proportion.

DOUGLAS ADAMS

One of my favorite sillinesses (sillini?) about the human condition is the distance between our self-image and our situation — the gap between how big we feel and how small we are. It is the central joke in the human comedy. I make myself the butt of that joke just about every day.

Every time I sit down to post a blog entry, I feel a twitch of self-loathing — until I remember I’m not significant enough to hate, at which point I laugh at myself and blog about it. At which point etc.

Case in point: my self-worth continues to be joined at the hip with the Amazon rank of Parenting Beyond Belief. To see a running chart of my mood for the past couple of months, click here. Note the horrible slide during the post-Newsweek-dry-pipeline debacle of late July, which I won’t even mention.

The book launched in the second week of April in Amazon’s top 0.1% — around 3,300 out of 3.5 million. This was good, because the success or failure of this book (frankly) will determine whether or not I make a go of authoring as a second career. Just when you thought it was all about raising the next generation of freethinkers, eh? I have five other books in the pipeline, you know, dammit, three of them finished and waiting for publishers. Anyway.

Two days ago, the Amazon rank dipped for a moment to 6600. This is still outrageously good for a book of this type, especially so far after launch, and yes, I know that most authors would sell their sisters to hit 6600 at all — gee hey, how’s my novel doing? — but having become all-too-accustomed to that top 0.1%, my mood darkened several clicks anyway. I had my 4 o’clock G&T at 2:30. A mistake I had made for my favorite freelance client was crushing my conscience. I was a failure as a father, as a husband, as a provider, as a writer, as a citizen of the world.

This morning, as we entered the sixth month of availability, the rank is at 2,600, and everything reversed. I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me. I am Leonardo DiCaprio on the bow of the Titanic, albeit better-looking.

The eye-rollingly pathetic lunacy of both of these reactions is plenty clear to me without help, thangyavurrymush. But help was present nonetheless on the same screen that brought me both ends of that silly-monkey emotional spectrum:

It’s M104, the Sombrero Galaxy, among the more elegant things in space and (lucky it) my current desktop background. And it doesn’t care what my Amazon rank is. It doesn’t care what I am. Nor do any of the quadrillion intelligent beings who most likely live in M104 know or care that one of the species on one planet in the galaxy they call “that smudge” has named their galaxy after a hat.

It is some comfort to realize that they surely have their sillini, too.

I’ll close with a perspective booster that made each of my three kids say OMIGOSH, NOWAY, or YOUGOTTABEKIDDING three times in one minute:

It’s not a Total Perspective Vortex, but as Douglas Adams pointed out, don’t even wish for that.

carl…is that you?

- August 31, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In Parenting, Science, wonder

19

19

I can’t remember the last time I was so delighted by an essay that I actually sat down and recopied it. Probably something by Carl Sagan. Here’s an excerpt of something that’s very much up Carl’s alley — an alley that happens to run smack-dab into my own.

From Sky and Telescope, August 2007, p. 102:

We Are Stardust: Spread the Word

BY DANIEL HUDONI FIRST HEARD the phrase in Joni Mitchell’s song Woodstock: “We are stardust. We are golden. We are billion-year-old carbon.” I next came across it while reading Carl Sagan’s Cosmos. But as with any other profound idea, it took years to sink in. Hearing it again at a recent lecture, I realized I could hear it every day for the rest of my life and still be amazed.

Think about it. In their hot, dense cores, stars are fusing light elements into the heavy ones crucial for life, such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and iron. The tiny bits of unused matter left over from these thermonuclear reactions become starlight via the most famous formula in physics, Einstein’s E=mc2.

We’ve known this for only half a century. In 1957 Alastair Cameron, Margaret and Geoffrey Burbidge, William Fowler, and Fred Hoyle solved the mystery of the origin of the elements. They showed that except for hydrogen, most helium, and traces of other light elements born in the Big Bang, everything else has been cooked up in stars.

It gets better. While low-mass dwarf stars like the Sun keep most products of their reactions locked up inside, high-mass supergiant stars spread the wealth in self-obliterating explosions known as supernovae. Some of Earth’s rarest elements (such as gold and uranium) are so scarce because they’re forged only in the spectacular deaths of rare massive stars.

On average, I heard in the same lecture, each atom in our bodies has been processed through five generations of stars. So we’re not just stardust — we’re stardust five times over, billions of years in the making!

Daniel goes on to suggest that we all remind each other of this incredibly profound fact in everyday exchanges (“Hi, my name is John. “Pleased to meet you. Did you know we’re made of stardust?”). He concludes:

Knowing this curious fact can give us pride in our origins: it’s like we’re descended from royalty — only better. Our stellar legacy connects us to the universe and to each other. Like the song says, we are golden — we are stardust. All of us.

If your kids had King Arthur as an ancestor, you’d coo it to them in their cribs. But have you told them yet that they’re descended from the stars? If they don’t know yet — geez, folks, what are you waiting for?

(For the complete Hudon essay, pick up the August S&T and flip to the back.)

The distiller’s art

Distillation’s been on my mind lately — the art of condensing something ungraspably large into a graspable essence. I mentioned Carl Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar a few weeks ago, a distillation of universal history that instantly focused my understanding of just how recent we are — and how small we are, and how deep and silly our delusions of bigness are.

Distilling space

Here’s another distillation of a sort:

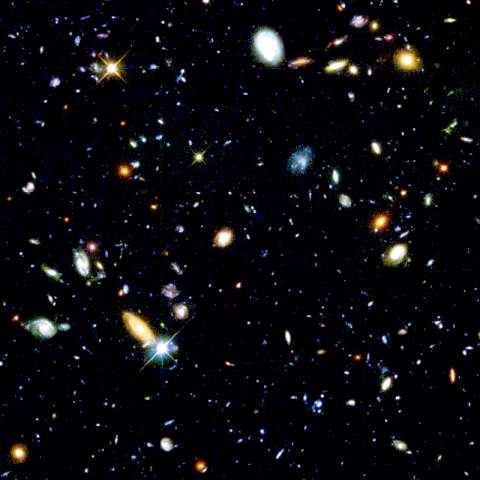

This image, called the Hubble Deep Field, must be the greatest picture of all time, a deep space image by the Hubble Telescope. How much sky does this represent? Imagine a dime held 75 feet away. The portion of the sky that dime would cover is the portion represented here. And it’s a patch of sky that appears essentially empty when viewed by ordinary telescopes. Most of the dots of light are not stars but galaxies. And this is one infinitesimal dot of space.

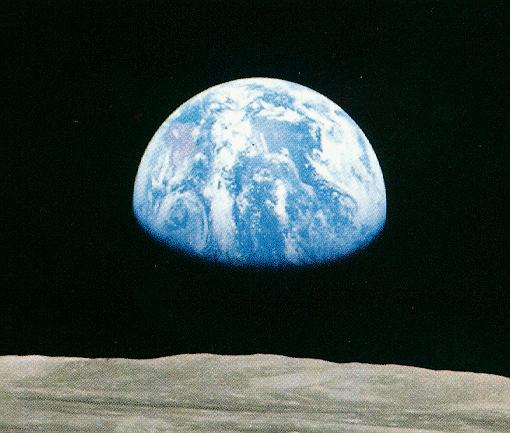

The Hubble Deep Field is my laptop background, and I sometimes find myself staring at it for ten minutes at a whack. It rivals Voyager’s famous “pale blue dot” photo and the first glimpse of Earthrise from the Moon for the granting of instant and lasting perspective for those who are awake:

You are here: The tiny dot is Earth viewed from Voyager II.

The 1968 paradigm rattler.

I love the particular headrush you get from this kind of distilled reality, the epiphany (sorry, it’s the best word) that can be achieved by snapshots capturing essences otherwise too large to grasp. In a single glance, I GET it.

Distilling time

Here’s another one:

That won’t mean anything to you normals, but having spent 25 years studying or teaching music theory, it’s something that makes me swoon. Music is notoriously tricky to get your hands on. Visual art is form and color arrayed across space, so you can snap on the rubber glove and it’ll hold still for the examination. Music, by contrast, is sound arrayed across time. Time is its body, so you can’t get it to hold still without killing it.

“If you try and take a cat apart to see how it works,” said Douglas Adams, “the first thing you have on your hands is a non-working cat.”

An Austrian music theorist named Heinrich Schenker developed a method for reducing a complex and ever-moving piece of music into a graspable snapshot. The chart above is a Beethoven string quartet movement of nearly 400 measures reduced to its essence. Foreground, middleground, and background, harmony and melody, it’s all there.

And–it’s not all there. Schenker didn’t intend this to replace music, but to give a little window of understanding, another way to GET it. I love to listen to Beethoven quartets, and I love to understand them as well. Then listening while understanding — don’t get me started.

Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar, mentioned above, is another time distiller, of course.

Distilling thoughts

Books are another tough nut to crack. By the time you get to the end of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, or The God Delusion, or Left Behind #13 — Kingdom Come, the sense of what a given book was “about” can reasonably vary from person to person. A friend reads Dawkins and hears a constant stream of invective. I read Dawkins and hear a constant stream of reasoned argument. No point saying one of us is definitively right or wrong. But there is one kind of snapshot distillation that I think sheds some interesting light — the concordance.

One type of concordance is a list of all the words appearing in a given book. Not the same as an index, which is a list of all concepts, whether or not they appear verbatim in the book. Somewhat subjective, the index. A concordance simply counts and reports. The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, for example, includes a long concordance that is misnamed “Index.” In it, you can find the apparent only significant use of the word “maggot-pie” — by Shakespeare, who else — and learn that the great quotesmiths have preferred to go on about love (586 times) more than hate (72 times). That’s nice.

But there’s another kind of concordance, one that can grant a bit of that snapshot distillation I’m on about. This kind records the most frequent words in a book.

If you hate “reductionism” — I myself happen to have a lifelong schoolboy crush on it, dotting its ‘i’s with little hearts as I write its name a thousand times on my three-ring binder — but if you hate it, you’ll hate concordances. They don’t reveal everything about a book, of course. If a concordance says the word MEAN appears 632 times in a book, does that indicate an obsession with hostility, or with significance, or with mathematical averages? And even if it is about hostility, is the book fer it or agin it? Maybe “mean” is always preceded by the phrase please don’t be.

The Hubble photo doesn’t tell us everything about the universe, either. It just gives us an insight, a new way of seeing it. Same with the concordance.

(Okay, the casual readers have long since gone. As a reward for the rest of you, here comes the point.)

I don’t know whether you’ve noticed, but for the past several months, Amazon.com has been sprouting new features like a house afire. My favorite new feature is, of course, the concordance. The 100 most common words in a given book are arrayed in a 10×10 block with font sizes varying by frequency. Huge-fonted words appear a lot, medium-fonted words etc. You get a fairly powerful sense of content, approach, and tone at a glance. I daresay I could show you concordances for books by Benedict XVI and Lenny Bruce and you’d know which was which — and which you’d rather read. (No no, don’t tell me, I’m keen to guess.)

Here, for example, is a concordance for one of my favorite recent books. Just looking at those hundred words makes me want to read it a fourth time.

The Point

Below are concordances for two parenting books, with the 100 most common words in order of frequency (in batches of ten for easier reading). One is about raising kids using biblical principles; the other is about raising kids without religion. See if you can tell which is which, and whether the concordances reveal anything about content, approach, and tone:

BOOK A

1-10: children—parents—god—child—love—own—husband—family—lord—word

11-20: wife—teach—heart—sin—christ—father—need—life—things—even

21-30: kids—should—man—must—son—proverbs—parenting—mother—does—scripture

31-40: kind—wisdom—evil—first—church—shall—may—home—fear—authority

41-50: marriage—obey—christian—ephesians—law—work—right—come—principle—means

51-60: take—truth—wives—woman—time—true—good—himself—solomon—give

61-70: live—men—let—paul—role—society—duty—honor—commandment

71-80: obedience—responsibility—teaching—against—gospel—know—therefore—verse—discipline—people

81-90: submit—something—themselves—jesus—want—women—wrong—world—day—think

91-100: instruction—faith—always—attitude—command—ing—certainly—spiritual—genesis—now

BOOK B

1-10: children—god—parents—religious—time—people—child—good—things—life

11-20: family—religion—world—think—believe—secular—know—even—beliefs—may

21-30: years—questions—own—right—kids—human—death—reason—first—school

31-40: idea—need—day—should—ing—moral—see—live—want—new

41-50: book—help—now—find—say—take—work—answer—others—something

51-60: church—come—wonder—bob—values—age—friends—get—go—little

61-70: does—without—long—often—true—thinking—feel—stories—must—love

71-80: exist—part—give—important—really—animals—two—great—kind—might

81-90: humanist—best—look—seems—still—atheist—few—thought—mean—mind

91-100:kobir—different—though—meaning—experience—problem—always—fact—adults—ceremony

Book A is

Book B is

The first observation is among the most interesting: that these two books, though different in many, many ways, have the same top three words. Even more interesting is that the secular parenting book mentions God more often. Not entirely surprising if you think about it. The top four words in Quitting Smoking for Dummies are SMOKING, SMOKE, TOBACCO, and CIGARETTES.

Next we notice a few surprises, like the fact that the concordance program promotes the suffix ‘ing’ to the status of a word, and that a dialogue in my book ends us up with the speakers’ names — Bob and Kobir — at #54 and #91, respectively.

Right, right…the point

One of the first things I noticed in comparing the two is the relative importance of obedience. What the Bible Says About Parenting uses the word OBEY 66 times and OBEDIENCE 49 times, while the same words appear only six and four times (respectively) in Parenting Beyond Belief — even though PBB is almost exactly twice as long. As a percentage of text, these words appear twenty-two times more frequently in the religious parenting book than in the non-religious one. I find that revealing, though not exactly surprising. I want my kids to know how to obey, sure, but it’s sixth or seventh on the list of my hopes for them (as I’ve written elsewhere). Seems a tad higher on the list for What the Bible.

What about parenting books in-between? I looked at two current mainstream bestsellers, Parenting From the Inside Out and I Was a Really Good Mom Before I Had Kids — neither of which includes OBEY or OBEDIENCE in its concordance. Religion and obedience seem particular stablemates.

I’m dismayed, but again unsurprised, that love is #5 in WTB and #69 in PBB. To tell the truth, I’m relieved it’s in our top 100 at all. Freethinkers love no less, of course, but we spend most of our time talking about truth and generally let love take care of itself. Religious folks often do the opposite, talking of endless love and letting truth tag along if it can keep up. And lo and behold, THINK is #14 for us and #89 for them. Also high in our list are the lovely words QUESTIONS (#22) and IDEA (#31) — neither of which appears in the other list.

The presence of words like HUSBAND, WIFE, SON, MOTHER, and FATHER high in the WTB list might indicate that role divisions are important. None of these appear in the PBB hit parade, which I think indicates less emphasis on divided roles. Perhaps I’m reading too much into these things. (READER: No no, I think you’re onto something!)

The presence of EPHESIANS on the WTB list makes some sense, since the end of Ephesians lists several familial duties — ‘Wives, submit to your husbands as to the Lord,’ (5:22) ‘Husbands, love your wives’ (5:25). But the fact that EPHESIANS appears 64 times just baffled me — until I remembered one of the most chilling verses in the NT:

Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. Honor your father and mother — which is the first commandment with a promise — that it may go well with you and that you may enjoy long life on the earth (Eph 6:1-3).

The conditional phrase “that you may enjoy long life” is no metaphor: It refers directly to Deuteronomy 21:18-21:

If a man have a stubborn and rebellious son, which will not obey the voice of his father, or the voice of his mother, and that, when they have chastened him, will not hearken unto them; Then shall his father and his mother lay hold on him, and bring him out unto the elders of his city…and they shall say unto the elders of his city, This our son is stubborn and rebellious, he will not obey our voice…And all the men of his city shall stone him with stones, that he die.

(For those who insist the OT is no longer in force, that it was replaced by a “new covenant” in the NT, Jesus wants a word with you. Now.)

Neither Ephesians nor Deuteronomy appears in the PBB top 100. Phew. We write about how to talk to kids about death (#27), but these guys threaten them with it. Okay okay, not directly…but by quoting the hell out of Ephesians, some (not all) religious folks show their enthusiasm for ultimate punishments in no uncertain terms.

I could go on and on, pointing out the high frequency of words like SIN, DUTY, EVIL, FEAR, AUTHORITY, DISCIPLINE, COMMAND, COMMANDMENT, SUBMIT, LAW, and INSTRUCTION in WTB, and the absence of any of those in PBB’s top 100, and the wholly different brands of parenting implicit in such observations. I could. But it seems equally important to point out that not all religious parenting books share the numbingly authoritarian quality that the concordance of What the Bible Says About Parenting seems to bespeak. In fact, I’d like to show you another Christian parenting book that has almost NONE of the sad and disheartening earmarks of WTB, James Dobson, and the rest of that ilk. But I’m sleepy. Next time, then.

(Here’s the link to PBB’s Amazon concordance, btw.)