The Tragic Silence of Lili Boulanger (Vieille Priére Bouddhique)

- June 18, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

Laney’s List #10 (11 min)

There is no shortage of composers whose lives and work were cut short by an early death: Chopin 39, Gershwin 38, Mozart 35, Schubert 31. We know those names because they managed through skill and luck to get a foothold on posterity before they died. It’s intriguing to wonder what Chopin or Gershwin would have been writing at 40 or 50 and heartbreaking to know we’ll never know. But at least we have what we have.

Now consider a composer with all the skill but who died so young that we are forced to wonder what she might have been creating at 30. Or 28. Or 25.

Lili Boulanger may be the best composer you’ve never heard of. Born in Paris in 1893, she showed early musical talent and quickly developed a unique and compelling style as a composer, full of innovative textures and harmony. At 19 she won the Prix de Rome, the highest French honor for composers, the first woman to win the award. With it came a five-year stipend to live and work in Rome, but her failing health brought her home early, and she died of intestinal tuberculosis at 24.

Her death didn’t just silence a great composer. It was a cruel foreclosure on what would have been the first extensive body of large-scale composition by a woman.

It’s hard to find a field as male-dominated as classical composition, and not because women somehow lack the gene. You need a very specific and intensive education to become a composer, something women were often denied. You need time, which for women often meant freedom from domestic responsibilities. And you need to have someone take you seriously enough to mentor your talent, sponsor your concerts, publish your work, and occasionally hand you an entire orchestra to play with.

The fact that women composers until recently often had names like Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Clara Schumann, and Alma Mahler hints at the way they managed to get any hearing at all. But even these remarkable talents were generally confined to small forms — solo piano, songs, trios — and endured other restrictions. Referring to her brother Felix, Fanny Mendelssohn’s father told her in a letter that “Music will perhaps become his profession, while for you it can and must be only an ornament.”

Even those who broke through to the larger forms often did so in a shadow. When Amy Beach wrote the first symphony by an American woman and had it premiered by the Boston Symphony in 1896, it was promoted as a symphony “by the wife of the celebrated Boston surgeon Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach.” The score, the parts, and the program listed her only as “Mrs. HHA Beach.” Her husband disallowed any formal study of composition or income from her work and limited her to two concerts a year so that she could “live according to his status, that is, function as a society matron and patron of the arts”[1]

Lili Boulanger had found her way past the hurdles and through the maze. She was writing large-scale works of surpassing strength and originality and receiving the accolades of a composer on the cusp of a brilliant career.

Then she was gone.

Vieille Priére Bouddhique (Old Buddhist Prayer) is a setting for solo tenor, choir, and orchestra. Listen to the whole piece, but for a particular taste of what we lost, note the astonishing echoic texture and shifting harmonies at 5:32-6:00.

10. BOULANGER Vieille Priére Bouddhique (8:34)

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

Impossible Ravel (Alborada del Gracioso)

- June 16, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

16 min

Flavio~ CC BY 2.0

(#9 from Laney’s List)

Ifirst knew Ravel as the tightly-wound precisionist of Le Tombeau — then I heard this flaming swordfight of a piece.

He grew up in Basque country, 10 miles from Spain, and it shows here. “Alborada del Gracioso” (Morning Love Song of the Jester) started as a movement from a piano suite, but there’s no way a symphonic Jedi like Ravel was going to resist throwing this one to the orchestra.

I heard the orchestral version of “Alborada” first, and it took the top of my head off. For years it was my favorite piece by my favorite composer. Then I heard it had been written first for piano. This was like saying the rooftop dance scene from West Side Story was originally for finger puppets and slide whistle. Uh, no offense to the piano, somehow.

Then I heard the piano version, and it took me an hour to even FIND the top of my head.

Last time I started with the piano version of Tombeau, then orchestra. I’ll flip the script for this one. Note the triple-tonguing trumpet/horn/flute at 1:12-1:30, which (FYI) is not actually possible, then compare to the same impossible spot for piano.

RAVEL, “Alborada del Gracioso” from Miroirs (orch, 7:43)

Now put the genie back in the bottle. This performance is insane. Listen through 1:30 at least, just to hear what human fingers can evidently do.

RAVEL, “Alborada del Gracioso” from Miroirs (piano, 6:22)

RELATED

RELATED

Ravel in Two Colors (Le Tombeau de Couperin)

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

Ravel in Two Colors (Le Tombeau de Couperin)

- June 13, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

9 min

(#8 from Laney’s List)

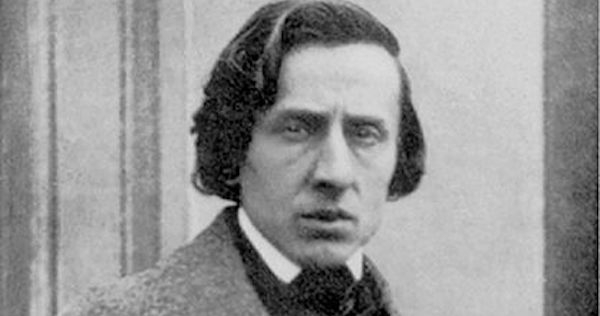

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) was meticulous. It’s hard to find a photo in which he’s not wearing a three-piece suit and pocket square, and his music is so tight it squeaks. He wrote slowly, sweating every detail, producing 85 compositions before he died at 62. Mozart by contrast wrote 626 pieces before dying at 35.

Ravel is sometimes lumped in with the Impressionists, and some of his work has that blurred, suggestive quality of impressionism. But more of it is crisp and linear, a return to elements of the style and form of Bach and Mozart that was eventually called Neoclassicism, pushing back against the dismantling of form and tonality by Schoenberg et al. I love and loathe the various fruits of that dismantling project, but for Ravel, I have nothing but love.

He was a stunning orchestrator and spent a great deal of time and energy rewriting piano compositions for orchestra. Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition is almost unknown in the piano original. What you’ve heard is Ravel’s brilliant orchestration of it. He also took the unusual step of orchestrating a number of pieces that he himself had first written for piano, including the piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917). The piece itself is a remembrance (tombeau) of the Baroque composer François Couperin, but each of the six movements is dedicated to the memory of a friend of Ravel’s who had died in the First World War, published as the war was still busily decimating a generation.

Here are two versions of a short Ravel piece side by side — the first movement of Ravel’s Tombeau for piano, then for orchestra.

RAVEL, “Prelude” from Le Tombeau de Couperin for piano (3:05)

RAVEL, “Prelude” from Le Tombeau de Couperin for orchestra (3:30)

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Ravel portrait by Véronique Fournier-Pouyet, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Click LIKE below to follow on Facebook…

What Is It About This Aria? (Delibes, Flower Duet)

- June 12, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

5 min

(#7 in the Laney’s List series — a music prof chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

I usually know why a piece of music slays me. It’s kind of my thing. But here’s a piece that I think is absolutely captivating, and I’m not entirely sure why that is.

Sure, I can find a captivating thing or three. The way the sopranos separate at the beginning of each measure, then join and rise together in thirds is an aural dance if ever there was, and 1:40-2:07 is some of the most elegant vocal writing I’ve ever heard. But I’m already sold by the time I get to 1:40, so that’s not it.

The chords are elegant and slightly nonstandard in that I’m-a-pretty-little-Frenchman way that makes me think of Satie at his Gymnopediest. If the second chord (1:10) had been V, for example, it would have been clunky and ordinary. Going to IV7 instead is just lovely. And the chord at 1:16, the one that ends the phrase! Instead of your average half cadence on V , he ends on iii. My keyboard is on the fritz (sorry, I mean on the françois) or I’d give you two sound files to show the difference. But just listen to that moment at 1:16 and see if you don’t hear a wistful harmonic lift-and-sigh in the strings. Nothing says This piece was built within ten years and ten kilometres of the Eiffel Tower like a phrase that ends on iii.

Still, I’m not convinced those details are the whole boule de cire. What do you think?

7. DELIBES “Flower Duet” from Lakmé (3:35)

See also: 1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | Full list | YouTube playlist

Look, It’s Just Cool (Reich Sextet)

- June 10, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

5 min

(#6 in the Laney’s List series — a music prof chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

Five composers especially haunt Laney’s List, coming back 3-4 times each. Four I could have predicted — Chopin, Bach, Mozart, Ravel. But until I started whittling, I didn’t know I’d give minimalist Steve Reich a trifecta as well.

Minimalism is the pendulum swing that followed the mid-20th century throwing-a-chair-while-barking school of it-is-totally-music-yuh-huh-is-so composition. It is mostly triads and conventional harmony, mostly simple patterns slowly changing over time, and represented a major palate cleanser after the avant garde of Varèse et al.

Terry Riley and Philip Glass are the emblematic pioneers of minimalism. But just as it’s Chopin representing the nocturne in this list, not Irish composer and nocturne inventor John “Who?” Field, so Reich is my go-to for minimalism. And in this list, like a good minimalist, he repeats.

Minimalism is not for everyone, so I’m starting in the relative shallows — a short interior movement of Reich’s Sextet for four percussionists and two pianos (1985). No major analysis required — it’s just cool. Things I love:

- The great contrast between those dense, massive hits of mixed dry and wet sound and that telegraphic vibraphone.

- The surprisingly chill melodic figure in the vibes at 0:26, like a ring tone interrupting General Patton’s speech.

- The way those two characters interact for the rest of the short movement.

I think nearly everything Reich does is interesting and cool, but I know it’s not for everyone. That’s why I’ve included three pieces of his in the list, increasing in conceptual difficulty. As Germany can tell you, sometimes it takes three Reichs to know they just aren’t your thing.

REICH, “Slow” from Sextet

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Chopin Had Just One Request (Impromptu No. 4)

- June 07, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

6 min

(#5 in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

If Chopin had his way, you wouldn’t know his Impromptu No. 4. Written in 1834 when he was 24 years old, it was not published until he was 45, by which time he had stopped writing new works entirely, having been dead for six years.

He had asked nicely that his unpublished works (including this one) remain unpublished after his death, which seems reasonable. But Posterity invoked the legal principle quid facietis in hac — roughly, What are you going to do about it? — and published anyway. It is now among his most performed pieces.

It starts with the fantastic agitated energy of his etudes, then goes into a tranquil melody that he clearly borrowed from the Judy Garland song “I’m Always Chasing Rainbows.”

Enjoy.

CHOPIN, Impromptu No. 4 (4:50)

See also: 1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow me on Facebook: