Concert Program Notes by Dale McGowan

The best program notes are engaging stories in clear language that enhance the listener’s experience of concert music. They should help the audience care more about the music, enjoy it more deeply, and retain more when they leave.

Dale McGowan brings 20 years as a conductor, composer, and professor of music to his concert program notes for ensembles including the Orchestra of Saints Catherine and Thomas, Rembrandt Chamber Musicians, and Berkeley Symphonic Band.

Excerpts

Franz Schubert: Piano Quintet in A Major, D. 667 (The Trout)

The piano quintet was created for a practical purpose: to rehearse or perform a piano concerto when a full orchestra was not at hand. One player from each of the four string sections (violin, viola, cello, and double bass) played from the orchestral parts to accompany the piano soloist.

Most of the piano quintets with a double bass quickly fell out of the repertoire, with one major exception: Franz Schubert’s Piano Quintet in A Major—“The Trout.”

Even as it creates challenges, the presence of a double bass opens new possibilities. By expanding the range of the strings down an octave, the bass provides a low “pitch floor” beneath the other strings, a feature on clear display in the opening bars. And by taking over the low end of the harmony, it frees the piano to spend more time in the high register, including the sparkling arpeggios in parallel octaves scattered throughout this piece.

You might say that Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet has less to do with trout than with bass.

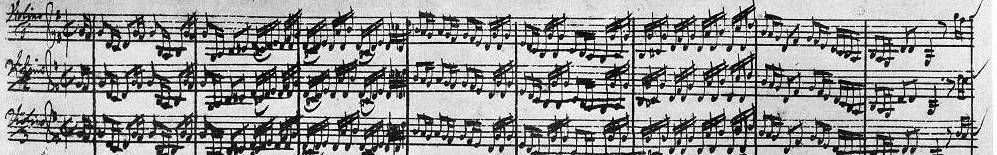

Johann Sebastian Bach: Concerto for Oboe and Violin in C Minor, BWV 1060R

Nearly 80 years passed after the death of Johann Sebastian Bach before his work began to draw the attention that would fix his place in the canon. Only then was a real effort begun to identify and catalog his works, a process that consumed more than a century. And by the time the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV) was finished in 1950, 17 works known to have once existed were listed as lost.

But there was a category even more intriguing—works only assumed from tantalizing clues to have once existed. Among these was a concerto in C minor for two unknown instruments, with strings and harpsichord continuo.

The evidence for its existence was a double harpsichord concerto in C minor, credited to Bach but in the handwriting of Johann Christoph Altnickol, his copyist and later son-in-law. All of Bach’s double-harpsichord concertos are thought to have been transcriptions of earlier works for other instruments. In most cases, both the original and the transcription survive, but the C minor concerto existed only in the double-harpsichord version. The original was gone.

An effort began in the 1920s to “reverse-engineer” the original concerto. Musicologists used the other double-harpsichord concertos, the ones for which both original and transcription still exist, as a kind of Rosetta stone for Bach’s transcription technique.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Viola Concerto in G Major, TWV 51:G9 (1721)

Composers vary wildly in their output. Duruflé produced only 23 compositions and Ravel 85, while Mozart had 626 and Bach 1,128. But all pale in comparison to Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767), a German composer with more than 3,000 compositions to his credit.

Telemann was a celebrated figure across Europe during his lifetime. But within 40 years of his death, his popularity plummeted and his works entered more than a century of obscurity. Half were lost, the rest unperformed. Telemann’s name, once acclaimed, became synonymous with mediocrity.

Part of the cause was the skyrocketing reputation of Bach in the early 19th century, to whom Telemann was unfavorably compared. At one point the insult Veilschreiber (“writer of quantity” instead of quality) was attached to Telemann by a Bach biographer. It became a faddish means of dismissing his work.

Yet two cantatas attributed to Bach and praised by Bach biographers as vastly superior to Telemann’s were discovered later to have been composed…by Telemann.

All content © 2023 Dale McGowan, PhD. All rights reserved.

J.S. Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major, BWV 1049 (1721)

When Bach presented the scores of six concertos for diverse instruments to the Margrave of Brandenburg in 1721, he added a dedication:

As I had the good fortune a few years ago to be heard by Your Royal Highness, at Your Highness’s commands,” he wrote in the dedication, “and as I noticed then that Your Highness took some pleasure in the little talents which Heaven has given me for Music… I have nothing more at heart, than to be able to be employed in some opportunities more worthy of Him and of his service…

It was essentially a job application, though not a successful one. That’s not because of the concertos themselves, which were shelved and never heard in Bach’s lifetime nor for a century afterward. The scores were discovered in the Brandenburg archive in 1849, published and performed—and promptly recognized as six masterworks at or near the pinnacle of Bach’s oeuvre.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) – from a program bio

He is alone—hair and clothes unkempt, face in a scowl, sitting at a piano in a darkening room, scratching notes furiously onto scattered papers. No other composer is fused as tightly to his popular image as Beethoven. His story was irresistible to the mythmaking of the Romantic era he helped launch and define—the musical genius who persevered despite encroaching deafness, pioneering innovations of form and style and harmony in masterworks he would never hear, creating beauty and power even as he was consumed by rage against the silence.

The darkness that colored his outlook in his 30s as the deafness intensified was not new; it pulled an existing thread in his temperament. The myth then grew from his very real struggle against what must have felt like ironic punishment for an unnamed crime, one that drove him to describe thoughts of suicide in a heartfelt letter to his brothers in 1802:

What a humiliation when someone stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing and again I heard nothing, such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, but little more and I would have put an end to my life – only art it was that withheld me, ah it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce…

He was 31, with nearly all of his greatest works ahead.

All content © 2020 Dale McGowan, PhD. All rights reserved.

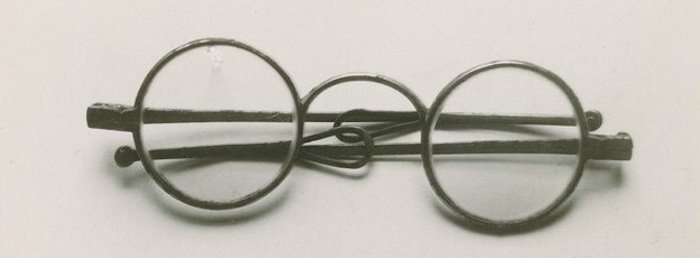

Beethoven: Duet with Two Obbligato Eyeglasses for viola and cello (1796)

More than 100 surviving notes and letters place one person near the center of every aspect of Beethoven’s life: Count Nikolaus Zmeskall von Domanovecz.

The notes reveal a relaxed, informal friendship. They socialized (“Let us meet at 6 o’clock at the Schwann Inn,” wrote Beethoven, “and drink some of their dreadful red wine”). They also made music together, and Zmeskall advised Beethoven about finances and the details of his career, even providing him with the special quill pens he used to copy his music (which Beethoven would request by writing, “Kindly pluck some feathers out of yourself”).

Beethoven often teased Zmeskall about the whiff of aristocracy in his title of Count. “To his most noble and well-born von Zmeskall,” starts a typical note, “Imperial and Royal, likewise Royal and Imperial Court Secretary, His high-born Von Zmeskall is requested kindly to say where one can speak with him to-morrow.” One note began with “Baron…Baron…Baron!” as lyrics set to a line of music. He called him “The Music Count,” “Your Highness,” “My Very Cheap Baron,” and “Dearest Scavenger of a Baron,” revealing both their casual relationship and Beethoven’s conflicted yearnings toward nobility.

In 1912, one movement of a duet for viola and cello was discovered among Beethoven’s folios—hastily scribbled even for Beethoven, partly illegible, and lacking such finishing touches as dynamics. A Minuet for the same instruments (with matching character, ink, paper, and sloppiness) was discovered in 1948 and determined to be the second movement. A presumed third movement, if ever written, was never found. In any case, the duet was clearly meant not for publication but for the private enjoyment of an audience of two—the composer and his closest friend.

The subtitle appended by Beethoven—“With Two Eyeglasses Obbligato”—alluded to the fact that the composer had recently joined his friend the Count in needing eyeglasses to read music.

Beethoven: Piano Trio in B-flat Major (Archduke), op. 97

One scene in Beethoven’s life is most often held up as the ultimate collision of triumph and tragedy—the composer being led to the edge of the stage after the premiere of his Ninth Symphony in 1824 to see the applause he could not hear. But another premiere, ten years earlier and a half mile away, rivals that moment for both triumph and tragedy: the premiere of the “Archduke” Piano Trio.

The last of his seven piano trios, the Archduke is also acclaimed as his finest, a capstone of his middle period. Dedicated to Archduke Rudolph, the piece was first performed publicly in May 1814 with the composer at the piano.

It did not go well.

All content © 2020 Dale McGowan PhD. All rights reserved.

Mozart: Quintet in E-flat Major for piano and winds, K. 452 (1784)

When Mozart described his Quintet in E-flat Major for piano and winds, K. 452, as “the best thing I have written in my life,” he was comparing it to 451 previous compositions—including 16 string quartets, 16 piano concertos, 37 symphonies, and a dozen operas—all by no less a composer than Mozart.

Not all great composers write well for every medium. Mention Beethoven to a singer if you doubt that. But Mozart achieved a rare mastery across the board by studying the nuances, limits, and possibilities of piano, voice, and every instrument of the orchestra until he could call on each to its maximum potential. Nowhere is this clearer than in his writing for winds. By knowing intimately how each of these idiosyncratic instruments sounds in every part of its range, Mozart then applies spacing and articulation to create textures that are clear, elegant, sparkling, and energetic in turn.

Carl Nielsen: Wind Quintet, op.43 (1922)

On a fall evening in 1921, the telephone rang in the home of Danish pianist Christian Christiansen. The caller was his friend and musical collaborator Carl Nielsen, the foremost living Danish composer.

Minutes into the conversation, Nielsen stopped mid-sentence to ask what on Earth he was hearing in the background. Christiansen explained that he was accompanying four members of the Copenhagen Wind Quintet— flute, oboe, French horn, bassoon—as they rehearsed a sinfonia concertante by Mozart. The winds had continued the rehearsal in the next room as he took the call.

The composer was so captivated by what he heard that he asked if he could come by immediately to hear it firsthand. Minutes later he was there, and the rehearsal resumed.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 4 in G Major, arr. for chamber ensemble by Erwin Stein (1921)

Reducing the instrumentation of a Mahler symphony to a chamber ensemble is like taking half of Michelangelo’s colors away and expecting the Sistine Chapel. If Bach is counterpoint and Schubert is melody, Mahler is all about instrumental color, especially in his symphonies. And in his Fourth Symphony, Mahler’s astonishing skill in using the shifting colors of this palette is evident from the opening bells and flutes to the kaleidoscopic Scherzo to the unexpected tranquility of the finale. A daunting assignment.

But the point of the reduction was not to duplicate the original; it was to expose its bones, resulting in what Schoenberg called “a clarity of presentation…often not possible in a rendition obscured by the richness of orchestration.”

The ingenious Stein arrangement was performed, well-received—and promptly lost.

Carl Nielsen, “Humoreske” from Symphony No. 6 (1925)

Right from the start, an argument seems to unfold. After a triangle roll, piccolo and bassoon chirp and belch (respectively) as if testing the waters, not yet knowing how to properly speak. A pause, then an impatient snare drum stirs the ensemble to life. All of the players chime in, confusedly, awkwardly, unsure of their abilities but falling over each other to be heard nonetheless. A clarinet attempts to build consensus among the winds, but eventually they fall into sparring pairs, like against like, two clarinets on one route and two bassoons on another. The piccolo remains confused, the trombone remains asleep, and the percussion lead the whole cacophony to a hideous explosion. Out of the debris, the drums try to restore order with a march-like figure. But the woodwinds steal the idea, creating the first real music of the movement. The trombone yawns loudly and often. Then the music accelerates, wrestles with itself, and eventually stumbles, groans, and falls into a scatter of rubble on the floor.

At least that’s one way to make sense of the oddest four minutes in Nielsen’s work.

All content © 2020 Dale McGowan PhD. All rights reserved.