Where all roads lead (2)

[Back to Part 1]

We’d had the conversation before, but this time a new dawning crossed Laney’s face.

“Sweetie, what is it?” I asked.

She began the deep, aching cry that accompanies her saddest realizations, and sobbed:

“I don’t want to die.”

Now let’s freeze this tableau for a moment and make a few things clear. The first is that I love this child so much I would throw myself under Pat Robertson for her. She’s one of just four people whose health and happiness are vital to my own. When she is sad, I want to make her happy. It’s one of the simplest equations in my life.

I say such obvious things because it is often assumed that nonreligious parents respond to their children’s fears of death by saying, in essence, Suck it up, worm food. When one early reviewer of Parenting Beyond Belief implied that that was the book’s approach, I tore him a new one. I am convinced that there are real comforts to be found in a naturalistic view of death, that our mortality lends a new preciousness to life, and that it is not just more truthful but more humane and more loving to introduce the concept of a life that truly ends than it is to proffer an immortality their inquiring minds will have to painfully discard later.

But all my smiling confidence threatens to dissolve under the tears of my children.

“I know, punkin,” I said, cradling her head as she convulsed with sobs. “Nobody wants to die. I sure don’t. But you know what? First you get to live for a hundred years. Think about that. You’ll be older than Great-Grandma Huey!”

It’s a cheap opening gambit. It worked the last time we had this conversation, when Laney was four.

Not this time.

“But it will come,” she said, hiffing. “Even if it’s a long way away, it will come, and I don’t want it to! I want to stay alive!”

I took a deep breath. “I know,” I said. “It’s such a strange thing to think about. Sometimes it scares me. But you know what? Whenever I’m scared of dying, I remember that being scared means I’m not understanding it right.”

She stopped hiffing and looked at me. “I don’t get it.”

“Well what do you think being dead is like?”

She thought for a minute. “It’s like you’re all still and it’s dark forever.”

A chill went down my spine. She had described my childhood image of death precisely. When I pictured myself dead, it was me-floating-in-darkness-forever. It’s the most awful thing I can imagine. Hell would be better than an eternal, mute, insensate limbo.

“That’s how I think of it sometimes too. And that frrrrreaks me out! But that’s not how it is.”

“But how do you know?” she asked pleadingly. “How do you know what it’s like?”

“Because I’ve already been there.”

“What! Haha! No you haven’t!”

“Yes I have, and so have you.”

“What? No I haven’t.”

“After I die, I will be nowhere. I won’t be floating in darkness. There will be no Dale McGowan, right?”

“And millions of worms will eat your body!!” chirped Erin, unhelpfully.

“…”

“Well they will.”

“Uh…yeah. But I won’t care because I won’t be there.”

“Still.”

I turned back to her sister. “So a hundred years from now, I won’t be anywhere, right?”

“I guess so.”

“Okay. Now where was I a hundred years ago? Before I was born?”

“Where were you? You weren’t anywhere.”

“And was I afraid?”

“No, becau…OMIGOSH, IT’S THE SAME!!”

It hit both girls at the same instant. They bolted upright with looks of astonishment.

“Yep, it’s exactly the same. There’s no difference at all between not existing before you were born and not existing after you die. None. So if you weren’t scared then, you shouldn’t be scared about going back to it. I still get scared sometimes because I forget that. But then I try to really understand it again and I feel much better.”

The crisis was over, but they clearly wanted to keep going.

“You know something else I like to think about?” I asked. “I think about the egg that came down into my mommy’s tummy right before me. And the one before that, and before that. All of those people never even got a chance to exist, and they never will. There are billions and trillions of people who never even got a chance to be here. But I made it! I get a chance to be alive and playing and laughing and dancing and burping and farting…”

(Brief intermission for laughter and sound effects.)

“I could have just not existed forever — but instead, I get to be alive for a hundred years! And you too! Woohoo! We made it!”

“Omigosh,” Laney said, staring into space. “I’m like…the luckiest thing ever.”

“Exactly. So sometimes when I start to complain because it doesn’t last forever, I picture all those people who never existed telling me, ‘Hey, wait a minute. At least you got a chance. Don’t be piggy.'”

More sound effects, more laughter.

Coming to grips with mortality is a lifelong process, one that ebbs and flows for me, as I know it will for them. Delaney was perfectly fine going to sleep that night, and fine the next morning, and the morning after that. It will catch up to her again, but every time it comes it will be more familiar and potentially less frightening. We’ll talk about the other consolations — that every bit of you came from the stars and will return to the stars, the peaceful symphony of endorphins that usually accompanies dying, and so on. If all goes well, her head start may help her come up with new consolations to share with the rest of us.

In his brilliant classic The Tangled Wing, Emory psychologist Melvin Konner notes that “from age three to five [children] consider [death] reversible, resembling a journey or sleep. After six they view it as a fact of life but a very remote one” (p. 369). Though rates of development vary, Konner places the first true grasp of the finality and universality of death around age ten—a realization that includes the first dawning deep awareness that it applies to them as well. So grappling with the concept early, before we are paralyzed by the fear of it, can go a long way toward fending off that fear in the long run.

In his brilliant classic The Tangled Wing, Emory psychologist Melvin Konner notes that “from age three to five [children] consider [death] reversible, resembling a journey or sleep. After six they view it as a fact of life but a very remote one” (p. 369). Though rates of development vary, Konner places the first true grasp of the finality and universality of death around age ten—a realization that includes the first dawning deep awareness that it applies to them as well. So grappling with the concept early, before we are paralyzed by the fear of it, can go a long way toward fending off that fear in the long run.

Laney, for better and worse, is ahead of the curve. All I can do is keep reminding her, and myself, that knowing and understanding something helps tame our fears. It may not completely feed the bulldog — the fear is too deeply ingrained to ever go completely — but it’s a bigger, better Milk-Bone than anything else we have.

Where all roads lead (1)

I have 22 posts jostling for attention at the moment, but a Saturday night conversation with my girls has sent all other topics back to the green room for a smoke.

The three of us were lying on my bed, looking at the ceiling and talking about the day. “Dad, I have to tell you a thing. Promise you won’t get mad,” said Delaney (6), giving me the blinky doe eyes. “Promise?”

“Oh jeez, Laney, so dramatic,” said Erin, pot-to-kettlishly.

“I plan to be furious,” I said. “Out with it.”

“Okay, fine. I…I kind of got into a God fight in the cafeteria yesterday.”

I pictured children barricaded behind overturned cafeteria tables, lobbing Buddha-shaped meatballs, Flying Spaghetti Monsters, and Jesus tortillas at each other. A high-pitched voice off-camera shouts Allahu akbar!

“What’s a ‘God fight’?”

“Well I asked Courtney if she could come over on Sunday, and she said, ‘No, my family will be in church of course.’ And I said oh, what church do you go to? And she said she didn’t know, and she asked what church we go to. And I said we don’t go to church, and she said ‘Don’t you believe in God?’, and I said no, but I’m still thinking about it, and she said ‘But you HAVE to go to church and you HAVE to believe in God,” and I said no you don’t, different people can believe different things.”

Regular readers will recognize this as an almost letter-perfect transcript of a conversation Laney had with another friend last October.

I asked if the two of them were yelling or getting upset with each other. “No,” she said, “we were just talking.”

“Then I wouldn’t call it a fight. You were having a conversation about cool and interesting things.”

Delaney: Then Courtney said, ‘But if there isn’t a God, then how did the whole world and trees and people get made so perfect?’

Dad: Ooo, good question. What’d you say?

Delaney: I said, ‘But why did he make the murderers? And the bees with stingers? And the scorpions?’

Now I don’t know about you, but I doubt my first grade table banter rose to quite this level. Courtney had opened with the argument from design. Delaney countered with the argument from evil.

Delaney: But then I started wondering about how the world did get made. Do the scientists know?

I described Big Bang theory to her, something we had somehow never covered. Erin filled in the gaps with what she remembered from our own talk, that “gravity made the stars start burning,” and “the earth used to be all lava, and it cooled down.”

Laney was nodding, but her eyes were distant. “That’s cool,” she said at last. “But what made the bang happen in the first place?”

Connor had asked that exact question when he was five. I was so thrilled at the time that I wrote it into his fictional counterpart in my novel Calling Bernadette’s Bluff:

“Dad, how did the whole universe get made?”

Okay now. Teachable moment, Jack, don’t screw it up. “Well it’s like this. A long time ago – so long ago you wouldn’t even believe it – there was nothing anywhere but black space. And in the middle of all that nothing, there was all the world and the planets and stars and sun and everything all mashed into a tiny, tiny little ball, smaller than you could even see. And all of a sudden BOOOOOOOM!! The little ball exploded out and made the whole universe and the world and everything. Isn’t that amazing!”

Beat, beat, and…action. “Why did it do that? What made it explode?”

“Well, that’s a good question. Maybe it was just packed in so tight that it had to explode.”

“Maybe?” His forehead wrinkles. “So you mean nobody knows?”

“That’s right. Nobody knows for sure. “

“I don’t like that.”

“Well, you can become a scientist and help figure it out.”

“…”

“…”

“Dad, is God pretend?”

“Well, some people think he’s pretend and other people think he’s real.”

“How ’bout Jesus?”

“Well, he was probably a real guy for sure, one way or the other.”

Pause. “Well, we might never know if God is real, ’cause he’s up in the sky. But we can figure out if Jesus is real, ’cause he lived on the ground.”

“You’re way ahead of most people.”

“Uh huh. Dad?”

“Yeah, Con.”

“Would you still love me if all my boogers were squirtin’ out at you?” Pushes up the tip of his nose for maximum verité.

“No, Con, that’d pretty much tear it. Out you’d go.”

“I bet not.”

“Just try me.”

I told Laney the same thing—that we don’t know what caused the whole thing to start. “But some people think God did it,” I added.

She nodded.

“The only problem with that,” I said, “is that if God made everything, then who…”

“Oh my gosh!” Erin interrupted. “WHO MADE GOD?! I never thought of that!”

“Maybe another God made that God,” Laney offered.

“Maybe so, b…”

“OH WAIT!” she said. “Wait! But then who made THAT God? OMIGOSH!”

They giggled with excitement at their abilities. I can’t begin to describe how these moments move me. At ages six and ten, my girls had heard and rejected the cosmological (“First Cause”) argument within 30 seconds, using the same reasoning Bertrand Russell described in Why I Am Not a Christian:

I for a long time accepted the argument of the First Cause, until one day, at the age of eighteen, I read John Stuart Mill’s Autobiography, and I there found this sentence: “My father taught me that the question ‘Who made me?’ cannot be answered, since it immediately suggests the further question ‘Who made god?’” That very simple sentence showed me, as I still think, the fallacy in the argument of the First Cause. If everything must have a cause, then God must have a cause.

…and Russell in turn was describing Mill, as a child, discovering the same thing. I doubt that Mill’s father was less moved than I am by the realization that confident claims of “obviousness,” even when swathed in polysyllables and Latin, often have foundations so rotten that they can be neutered by thoughtful children.

There was more to come. Both girls sat up and barked excited questions and answers. We somehow ended up on Buddha, then reincarnation, then evolution, and the fact that we are literally related to trees, grass, squirrels, mosses, butterflies and blue whales.

It was an incredible freewheeling conversation I will never, ever forget. It led, as all honest roads eventually do, to the fact that everything that lives also dies. We’d had the conversation before, but this time a new dawning crossed Laney’s face.

“Sweetie, what is it?” I asked.

She began the deep, aching cry that accompanies her saddest realizations, and sobbed:

“I don’t want to die.”

Welcome to the World on PBS

The PBS series Religion & Ethics Newsweekly ran a nice segment on August 15 about the nonreligious baby naming ceremony I co-hosted at last September’s convention of Atheist Alliance International. The guests of honor were Lyra and Sophia Cherry, two-year-old twin daughters of Shannon and Matt Cherry (director of the Institute for Humanist Studies at the time). Several prominent freethinkers participated, including Richard Dawkins.

The ceremony itself was very well conceived, with readings, gifts, music, rich symbolism, a choked-up dad, and the pledging of mentors for each of the girls.

Matt wrote a lovely and thoughtful column about the event for On Faith, a site sponsored by the Washington Post and Newsweek. (Read the column here, and if you find yourself enveloped in a warm feeling about humanity when you finish it, do not go on to read the extremely depressing comment thread.)

The brief PBS video segment is here. Don’t blink and you’ll see and hear someone the script calls “UNIDENTIFIED MAN #1.” Hey Ma, c’est moi!

More on secular celebrations, including the complete script of the Cherry event, is here.

Looking back…and it’s about time (2 of 2)

Guest column by Becca McGowan

I don’t think there is a God; but I wish there was one.

There it is. I said it.

I had never actually said this to anyone until my seven-year-old daughter asked me point-blank, “Mom, do you believe in God?” It had been easy to avoid a concrete answer up to that point because virtually all religious conversations in our home were between Dale and the kids. I was content to listen during family discussions and participate only in the easy parts: Everybody believes different things…the bible is filled with stories that teach people…we should learn about other people’s beliefs…we should keep asking questions so we can decide what we think…those were the easy parts. I told myself that I was still thinking about it.

The problem is that deep down, I had already decided. And I had decided that God was not real. God was created from the human desire to explain what we didn’t understand. God was an always-supportive father figure, able to get us through difficult times when human fathers were insufficient. I now believed what I had only toyed with in Mr. Tresize’s high school mythology class: A thousand years from now, people will look back on our times and say, “Look, back then the Christian myth held that there was one God and that his son became man…”

But wait a minute! This can’t be! Did I actually say this out loud to my daughter?! I am a GOOD person. I am a KIND person. I help OTHERS. As I left for school each day as a little girl, my mother always said, “Remember, you are a Christian young lady.” That’s who I AM!

Now, here I was, a mother, encouraging my children to keep asking questions, keep reading, keep talking with others. I want my children to think and learn. Then, I tell them, decide for yourself.

But had I ever asked questions about religion? Had I ever read about religion or talked with others? Had I actually decided for myself? No. I became a church-attending Christian as a way to rebel against my stepfather. I hadn’t thought about it for a day in my life.

Flash back eight years, driving home from church in our minivan, when Dale said to me, “I just can’t go to church anymore.” I was devastated.

I continued to attend church on my own for a couple of years. I also began reading Karen Armstrong’s In the Beginning. And I began to think about why I believed. The more I read and talked and debated, the more I realized that my belief was based on my label as a “Christian young lady.” My belief was based on uniting with my mother against my stepfather.

I now consider myself a secular humanist, someone who believes that there is no supernatural power and that as humans, we have to rely on one another for support, encouragement and love. Looking at religious ideas and asking questions, thinking and talking and then finally coming to the realization that I was a secular humanist—that was not the difficult part. Breaking away from the expectations and dysfunctions of my family of origin has proven to be the real and ongoing challenge.

__________________

BECCA McGOWAN is a first grade teacher. She holds a BA in Psychology from UC Berkeley and a graduate teaching certificate from UCLA. She lives with her husband Dale and three children in Atlanta, Georgia.

On waking the heck up

To be awake is to be alive. I have never met a man who was quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?

From Walden by Henry David Thoreau

I was interviewed Tuesday for the satellite radio program “About Our Kids,” a production of Doctor Radio and the NYU Child Study Center, on the topic of Children and Spirituality. Also on the program was the editor of Beliefnet, whom I irritated only once that I could tell. Heh.

“Spirituality” has wildly different meanings to different people. When a Christian friend asked several years ago how we achieved spirituality in our home without religion, I asked if she would first define the term as she understood it.

“Well…spirituality,” she said. “You know—having a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and accepting him into your life as Lord and Savior.”

Erp. Yes, doing that without religion would be a neat trick.

So when the interviewer asked me if children need spirituality, I said sure, but offered a more helpful definition—one that doesn’t exclude 91 percent of the people who have ever lived. Spirituality is about being awake. It’s the attempt to transcend the mundane, sleepwalking experience of life we all fall into, to tap into the wonder of being a conscious and grateful thing in the midst of an astonishing universe. It doesn’t require religion. Religion can, in fact, and often does, blunt our awareness by substituting false (and dare I say inferior) wonders for real ones. It’s a fine joke on ourselves that most of what we call spirituality is actually about putting ourselves to sleep.

For maximum clarity, instead of “spiritual but not religious,” those so inclined could say “not religious–just awake.”

I didn’t say all that on the program, of course. That’s just between you, me, and the Internet. But I did offer as an example my children’s fascination with personal improbability – thinking about the billions of things that had to go just so for them to exist – and contrasted it with predestinationism, the idea that God works it all out for us, something most orthodox traditions embrace in one way or another. Personal improbability has transported my kids out of the everyday more than anything else so far.

Evolution is another. Taking a walk in woods over which you have been granted dominion is one kind of spirituality, I guess. But I find walking among squirrels, mosses, and redwoods that are my literal relatives to be a bit more foundation-rattling.

Another world-shaker is mortality itself, about which another small series soon. Mortality is often presented as a problem for the nonreligious, but in terms of rocking my world, it’s more of a solution. Spirituality is about transforming your perspective, transcending the everyday, right? One of my most profound ongoing “spiritual” influences is the lifelong contemplation of my life’s limits, the fact that it won’t go on forever. That fact grabs me by the collar and lifts me out of traffic more effectively than any religious idea I’ve ever heard. A different spiritual meat, to be sure, but no less powerful.

The program will air Friday August 8, 8-10am Eastern Time (US) on SIRIUS Satellite Channel 114—or listen online at Doctor Radio.

[BONUS QUESTION: Did you yawn when you saw the baby?]

not just another day

A few months ago I caught sight of a forehead-thumpingly dumb initiative called “Just Another Day,” an attempt by some atheist activists (including the usually level-headed Ellen Johnson) to encourage nonbelievers to treat the presidential election of November 4 as “just another day” by refusing to vote. The candidates are climbing over each other to pander to the faithful, went the reasoning, and until they begin to represent my interests as well as those of the religious majority, I’m taking my cool Pee-Wee Herman action figure home where no one else can play with it.

Solid proof that the religious have no monopoly on delusion and self-satire.

The initiative now seems to have been scrubbed from the Internet — no small feat. I can find no trace. And that’s good, because although both major candidates are indeed playing up their supercalinaturalistic bona fides, one of them has distinguished himself with comments like this:

If you have not heard this unprecedented, jaw-droppingly, hair-blow-backingly brilliant speech, here’s a longer clip. (I’ll paste it at the end as well.)

And then we have business as usual. (Is it true that we blink more rapidly when we know we are not being truthful?):

So one candidate appears to have read and understood the Constitution and (better yet) to have internalized its implications and its spirit, while the other has apparently read Chuck Colson.

Regardless of Obama’s personal religious beliefs, I find his grasp of this issue incredibly encouraging. I don’t need a president who shares my every view. I would like one with a solid handle on the principles on which the nation is predicated. And if I’m not mistaken, I’ve found one. So I’ll be in the sandbox with the rest of you on November 4.

And yes, you can play with my Pee-Wee.

__________________________________

A five-minute clip of Mr. Obama’s speech. Do not pass go until you hear it.

believe you me

The Meming of Life is back in the saddle after the third and final family reunion of the summer. The blog’s new look should be online shortly. Nine days from now, we will hear an alarm clock for the first (damn) time in three months as school resumes. Today my boy comes of age, beginning a year-long project that (should he choose to accept it) will culminate in a celebration, special gifts, new rights, and new responsibilities as he enters high school.

Posts to come on all of the above — but for now, let’s ease into August with something I’ve wanted to feature for some time…

I suggest in the seminars that nonreligious parents do what they can to make beliefs a normal topic of discussion in their extended families. Not that it is in mine — my poor dear relatives seem positively constipated on the topic of religion since my book came out. I think they’re hoping to avoid offending me, not realizing that (1) I am pert near unoffendable, and (2) I would be delighted if our differences could be openly acknowledged and we could talk to / joke with /challenge each about something more interesting than truck transmissions and Dancing With the Stars.

One guaranteed conversation starter is the Belief-O-Matic Quiz at Beliefnet.com. Take the quiz, talk about your results, and invite other family members to do the same.

The quiz asks twenty multiple choice worldview questions, then spits out a list of belief systems and your percentage of overlap with each system. In other words, it doesn’t tell you what church you go to, but it might tell you what church you should be going to. If any.

Email all family members the link before your next gathering.

My most recent result:

1. Secular Humanism (100%)

2. Unitarian Universalism (92%)

3. Liberal Quakers (76%)

4. Theravada Buddhism (73%)

5. Nontheist (73%)

6. Neo-Pagan (65%)

7. Mainline to Liberal Christian Protestants (59%)

8. New Age (49%)

9. Taoism (47%)

10. Orthodox Quaker (43%)

11. Reform Judaism (41%)

12. Mahayana Buddhism (41%)

13. Sikhism (32%)

14. Jainism (30%)

15. Bahá’í Faith (30%)

16. Scientology (28%)

17. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) (27%)

18. New Thought (25%)

19. Seventh Day Adventist (22%)

20. Christian Science (Church of Christ, Scientist) (20%)

21. Hinduism (20%)

22. Mainline to Conservative Christian/Protestant (20%)

23. Eastern Orthodox (18%)

24. Islam (18%)

25. Orthodox Judaism (18%)

26. Roman Catholic (18%)

27. Jehovah’s Witness (13%)

Now tell me that’s not a fun and interesting conversation starter.

In addition to being awfully Buddhist, I’m apparently less Jewish now (18 percent) than I was three years ago (38 percent) but slightly more Catholic (18 vs. 16 percent). And this is the most interesting feature of the quiz — the revealed common ground.

Even so, comparing results between people can carry a very different message. Just for sport, I took the quiz answering as if I were a Baptist evangelical:

1. Eastern Orthodox (100%)

2. Roman Catholic (100%)

3. Mainline to Conservative Christian/Protestant (99%)

4. Jehovah’s Witness (87%)

5. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) (83%)

6. Seventh Day Adventist (80%)

7. Orthodox Judaism (79%)

8. Islam (70%)

9. Orthodox Quaker (67%)

10. Hinduism (59%)

11. Sikhism (51%)

12. Mainline to Liberal Christian Protestants (40%)

13. Bahá’í Faith (37%)

14. Jainism (37%)

15. Reform Judaism (30%)

16. Christian Science (Church of Christ, Scientist) (21%)

17. Mahayana Buddhism (21%)

18. Theravada Buddhism (21%)

19. Liberal Quakers (20%)

20. Scientology (19%)

21. Nontheist (18%)

22. Unitarian Universalism (16%)

23. New Thought (15%)

24. Neo-Pagan (8%)

25. New Age (4%)

26. Taoism (2%)

27. Secular Humanism (0%)

Have the heart pills ready when Born-Again Grandma finds out she’s 70 percent Islamic.

It might seem surprising at first that Catholic and Conservative Protestant come out so close, but the differences in the two, like the devil himself, are primarily in the details. The quiz goes after foundational worldview questions, not the piles and piles of minutiae that kept the two at each others’ throats for so many centuries.

But take a look at the gap between conservative Christianity and secular humanism. It’s true that the churched and unchurched share an incredible amount of common ground as human beings, but when it comes to the worldview questions around which the quiz is built, a chasm opens. In the great metaphysical Q&A, my conservative relations and I share between zero and 20 percent.

So while we’re celebrating the humanistic ties that bind us, it doesn’t hurt to recognize the challenge faced by bridge builders on both sides.

Perhaps the most revealing result of the two lists is where mainline-to-liberal Christianity falls on each. I share 59 percent with the average liberal Christian, while our hypothetical conservative Baptist shares 40 percent with the liberal Christian. Mainline-Liberal Christians have a good deal more in common with secular humanists than they do with Pat Robertson and Benedict XVI. Both humanists and liberal Christians would benefit enormously from recognizing, and building on, this large overlap.

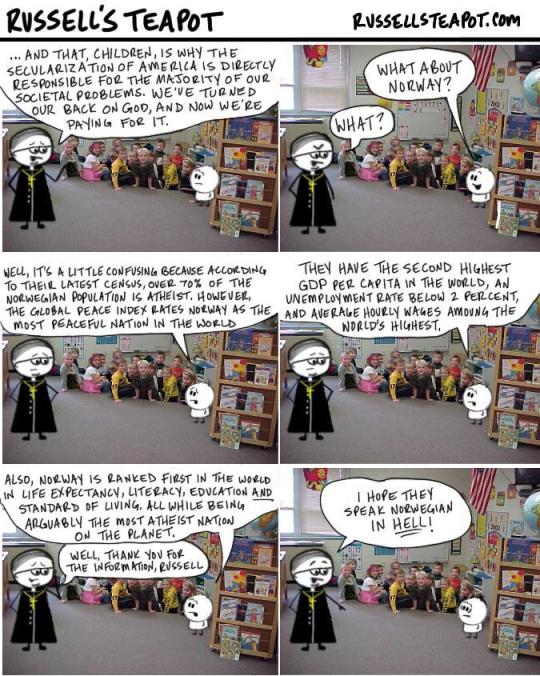

The humanistic hell that is Norway

As we pull together Connor’s coming of age process for the coming year, one country keeps popping its blonde head into the frame–Norway. No surprise: Norway is among the least theistic countries on Earth and has the longest continuous history of humanist coming-of-age ceremonies. I mentioned this in passing late last year:

One of the most marvelous and successful [humanist coming-of-age] programs in the world is the Humanist Confirmation program in Norway. According to the website of the Norwegian Humanist Association, 10,000 fifteen-year-old Norwegians each spring “go through a course where they discuss life stances and world religions, ethics and human sexuality, human rights and civic duties. At the end of the course the participants receive a diploma at a ceremony including music, poetry and speeches.” They are thereby confirmed not into atheism, but into the humanist values that underlie all aspects of civil society, including religion.

As for Norway itself, I could go on and on. It is among the nations with the lowest rates of crime and poverty while topping the developed world in generosity and nearly all standards of living. Yet fewer than 10 percent of Norwegians attend church regularly.

I’ll let Russell’s Teapot take it on home:

[CAVEAT LECTOR: The cartoonist has overreached a bit here. Sixty-eight percent of the Norwegian population self-identifies as nontheistic. A much smaller percentage (around 10 percent) self-identify as atheists. Hat tip to MoL reader Ellen!]

is nothing sacred? epilogue

I recently offered my thoughts on the difference between pointless and pointful challenges to sacredness:

Why does the David Mills video I’ve denounced strike me instantly as a profoundly stupid gesture, while [Webster Cook’s removal of a communion wafer from a mass] strikes me just as instantly as an interesting and thought-provoking transgression?

The reason, I think, is that the act of crossing the church threshold with that wafer (whether he intended this or not) is a kind of Gandhian gesture. Doing something so seemingly innocuous and eliciting an explosive, violent, even homicidal response is precisely the way Gandhi drew attention to cruel policies and actions of the British Raj, the way black patrons in the deep South asserted their right to sit on a bar stool, while whites (enforcing a kind of sacred tradition) went ballistic….

Mills’ feces-and-obscenity-strewn video, on the other hand, had offense not as a byproduct but as its intentional essence. Of Cook, one can say, “he just walked out the door with a wafer,” and the contrast with the fireworks that followed is clear. But saying, with sing-song innocence, that Mills was “just smearing dogshit on a book while swearing, gah,” doesn’t achieve quite the same clarity. Even though it shares the act of questioning the sacred, it’s much less interesting and much less defensible.

When PZ Myers of the science blog Pharyngula made known his intention to desecrate a communion wafer, I held my breath a tad, wondering which way it would go. Would he do something stupid or something thought-provoking? Pointless or pointful?

Now Myers has made his gesture — and I couldn’t be more thrilled:

This fascinates me even more than Wafergate because it is so achingly close to the Mills’ video on the surface, yet light years away in substance.

Had Myers theatrically smashed a pile of communion wafers with a hammer while laughing hysterically, he’d have undercut his own point that it is just a “frackin’ cracker.” Instead, he made use of that old and brilliant insight that the opposite of love is not hate but indifference.

So he quite simply threw it out, along with the coffee grounds.

Granted, he put a nail through it, a subtle and ironic comic touch that I’m doomed to love. But the real brilliance is in the background. Myers has also thrown out pages of the Koran and The God Delusion. He isn’t allowing anything to be held sacred. ALL ideas must be exposed to disrespect, disconfirmation, and disinterest. The good ones can take the abuse, and the bad ones, to quote Twain, will be “[blown] to rags and atoms at a blast.” If instead we shield a set of beliefs or ideas from scrutiny or attack, the bad bits survive along with the good.

Myers is also making the important point that these are NOT ideas in the garbage — they are paper and wheat, which must not be confused with the things they represent any more than a flag should be revered in lieu of the principles for which it stands.

Toss in a wink at Ray Comfort’s banana argument against atheism and the whole tableau simply rocks with meaning, power, humor and intelligence. And pointfulness.

Myers’ post is long, but please take a few minutes to read it. I can’t recommend it highly enough for its provision of context and just plain smarts. The final paragraph drives it all home:

Nothing must be held sacred. Question everything. God is not great, Jesus is not your lord, you are not disciples of any charismatic prophet. You are all human beings who must make your way through your life by thinking and learning, and you have the job of advancing humanities’ knowledge by winnowing out the errors of past generations and finding deeper understanding of reality. You will not find wisdom in rituals and sacraments and dogma, which build only self-satisfied ignorance, but you can find truth by looking at your world with fresh eyes and a questioning mind.

When it comes to challenging sacredness, if I can get my kids to grasp the difference between Mills and Myers, I’ll count myself proud.

is nothing sacred?

‘Body Of Christ’ Snatched From Church, Held Hostage By UCF Student

I smiled. I just love The Onion. Then I realized this was an actual news headline about an actual event. On Earth.

I hadn’t planned on writing about this. I’m trying to maintain a semblance of focus in this blog. But then the student’s father began defending his son in comment threads on Catholic blogs, and I had my parenting angle. Which I’ll get to. First, though, for the three of you who don’t know what I’m on about — the story that ran below that headline:

Church officials say UCF Student Senator Webster Cook was disruptive and disrespectful when he attended Mass held on campus Sunday June 29. It was during that Mass where Cook admits he obtained the Eucharist.

The Eucharist is a small bread wafer blessed by a priest. According to Catholics, the wafer becomes the Body of Christ once blessed and is to be consumed immediately after a minister passes it out to churchgoers.

Cook claims he planned to consume it, but first wanted to show it to a fellow student senator he brought to Mass who was curious about the Catholic faith.

“When I received the Eucharist, my intention was to bring it back to my seat to show him,” Cook said. “I took about three steps from the woman distributing the Eucharist and someone grabbed the inside of my elbow and blocked the path in front of me. At that point I put it in my mouth so they’d leave me alone and I went back to my seat and I removed it from my mouth.”

A church leader was watching, confronted Cook and tried to recover the sacred bread. Cook said she crossed the line and that’s why he brought it home with him.

“She came up behind me, grabbed my wrist with her right hand, with her left hand grabbed my fingers and was trying to pry them open to get the Eucharist out of my hand,” Cook said, adding she wouldn’t immediately take her hands off him despite several requests.

Cook is upset more than $40,000 in student fees have been allocated to support religious organizations on campus for the 2008-2009 school year, according to student government records. He denied he is holding the Eucharist hostage to protest that support.

Regardless of the reason, the Diocese says its main concern is to get the Eucharist back so it can be taken care of properly and with respect. Cook has been keeping the Eucharist stored in a plastic bag since last Sunday.

“It is hurtful,” said Father Migeul [sic] Gonzalez with the Diocese. “Imagine if they kidnapped somebody and you make a plea for that individual to please return that loved one to the family.”

The Diocese is dispatching a nun to UCF’s campus to oversee the next mass, protect the Eucharist and in hopes Cook will return it.

You will no doubt be shocked to learn that the student has received several death threats. As a result of that exalted terrorism, he has now returned the Divine Saltine.

Despite the fact that almost everyone in the story is acting like a baboon, this is not just a toss-off piece of silliness to me. It taps fascinating issues around the intersection of sacredness, tradition, tolerance, the media, force, academia, healthy snacking, and free expression. Most such stories are merely about baboons, but this one I simply can’t get out of my head.

Question #1: Why does the David Mills video I’ve denounced strike me instantly as a profoundly stupid gesture, while this strikes me just as instantly as an interesting and thought-provoking transgression?

The reason, I think, is that the act of crossing the church threshold with that wafer (whether he intended this or not) is a kind of Gandhian gesture. Doing something so seemingly innocuous and eliciting an explosive, violent, even homicidal response is precisely the way Gandhi drew attention to cruel policies and actions of the British Raj, the way black patrons in the deep South asserted their right to sit on a bar stool, while whites (enforcing a kind of sacred tradition) went ballistic.

No, the analogy is not perfect. Cook was not defending a right. But he did similarly draw attention to an element of belief (crackers are different once a priest’s hand has waved over them) that can tip quite suddenly into dangerous lunacy at the slightest provocation. Isn’t that a point worth making?

Mills’ feces-and-obscenity-strewn video, on the other hand, had offense not as a byproduct but as its intentional essence. Of Cook, one can say, “he just walked out the door with a wafer,” and the contrast with the fireworks that followed is clear. But saying, with sing-song innocence, that Mills was “just smearing dogshit on a book while swearing, gah,” doesn’t achieve quite the same clarity. Even though it shares the act of questioning the sacred, it’s much less interesting and much less defensible.

Question #2: Is nothing sacred?

Becca and I debated this at length. She said that all declarations of sacredness should be respected and left alone. I countered by saying the very idea of sacredness is worth discussing, and that the best way to draw attention to something of this kind — like an unjust law — is by violating it and allowing the results to play out. Should we “respect and leave alone” the opposing, irreconcilable claims of sacredness that keep the Middle East aflame? The sacred idea that men should have dominion over women? The list goes on.

But the question remains: Should anything be held “sacred”? I think the answer is yes and no, because the word “sacred” has two different major meanings.

Sacred is used to denote specialness, to mark something as awe-inspiring, worthy of veneration or deserving of respect. In this first sense, the nonreligious tend to hold many things sacred — life, integrity, knowledge, love, a sense of purpose, freedom of conscience, and much more. One might even hold sacred our right and duty to reject the second meaning of sacred: something inviolable, unquestionable, immune from challenge.

This second definition of sacredness is much like the concept of hell — it exists primarily as a thoughtstopper. As such, it has no place in a home energized by freethought. One of the most sacred (def. 1) principles of freethought is that no question is unaskable, no authority unquestionable.

Which bring me to Question #3, the parenting angle. If this were my son, and he had undertaken this as a kind of civil disobedience, would I be proud?

Immensely. Intensely. Uncontainably. It’s Kohlberg’s sixth stage of moral development, and it makes me weak in the knees.

Encouraging reckless inquiry in your kids means laughing the second definition of “sacred” straight out the door. Given that understanding of the dual meaning of sacredness, it should now make sense that I consider it a sacred duty to hold nothing sacred.