A Cricket in the Renaissance (Josquin – El Grillo)

High in the wall of the Sistine Chapel is a choir loft called the cantoria. Built in 1471, it was off limits to anyone but singers in the papal choir for 350 years. In the absence of adult supervision, centuries of singers carved their names in the wall. A member in the 1490s named Josquin des Prez (translation: Josquin of Prez) was one of them. This is interesting because he’s also generally considered the greatest Renaissance composer, and this graffito is the only surviving thing written in his own hand.

The great artists of the Renaissance were most often Italian — Michelangelo, da Vinci, Caravaggio, Raphael, Donatello. But as often as not, the best composers of the Renaissance were Franco-Flemish, meaning they were from northern Europe and had trouble clearing their throats.

Like most northern composers of the period, Josquin — usually referred to by the one name, like Plato or Beyoncé, and pronounced zhoss-KAN — spent most of his career in Italy, where wealthy families were engaged in the most artistically productive pissing contest of all time, to which Josquin contributed many powerful and elegant streams.

He was acknowledged as the greatest composer of his generation within his own lifetime, which is rare but nice. Like Bach two centuries later, Josquin wrote both sacred and secular works and excelled at both. The sacred music is really stunning:

1:12

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3qx_JjPrh5M” parameters=”end=72″ /]

But he could also let his hair down with secular songs. Here’s a frottola (the precursor to madrigal) about a cricket — short, funny, and kind of amazing:

El grillo, El grillo è buon cantore | The cricket is a good singer

che tiene longo verso | and he sings for a long time

Dalle beve grillo canta. | Give him a drink so he can go on singing

Ma non fa come gli altri uccelli | But he doesn’t do what the other birds do

come li han cantato un poco | Who after singing a little

van’ de fatto in altro loco | Just go elsewhere

sempre el grillo sta pur saldo | The cricket is always steadfast

Quando la maggior è [l’] caldo | When it is hottest

alhor canta sol per amore. | then he sings just for love

1:30

15. JOSQUIN frottola “El Grillo” (The Cricket) (1:30)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OI-bQ0RkArA” /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | 13 Mozart | 14 Reich | 15 Josquin | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale on Facebook:

Mozart in Eight Sobs (Lacrimosa)

12 min

(#13 in the Laney’s List series)

When my brother and I were teenagers, we knew just enough about music to be insufferable. We’d listen to something by Mozart that we hadn’t heard before, and as the end of each phrase approached, we would sing the last measures, then laugh at how spot-on we had guessed it. Stupid, predictable Mozart.

If you want to reach across the decades and slap us, you’ll have to wait behind him and me both.

Once Charles Rosen and some education and experience had their way with me, I realized that our spooky predictive powers stemmed from the fact that Mozart had done more than almost anyone in creating those expectations.

Mozart was a composer in the Classical style from his first harpsichord minuets at age four (K. 1) to the Requiem Mass at 35 (K. 626). Instead of destroying the box of the period he was born into, he explored and defined the box, then played every possible game with it before folding it up into an exquisite origami model of Vienna. So much for boxes, said Beethoven, who ran naked into the forest of Romanticism.

We’ll chase those retreating buns later.

But some of Mozart’s compositions did look forward to the Romantic style, and the Requiem was one of those — not just in the music, but in the web of mythology that was spun around it after his death.

Most of what most people think they know about Mozart’s Requiem came from the film and play Amadeus. The actual circumstances of its composition are almost as strange as the myths.

The play and film depict a shadowy commission of the Requiem from the gravely ill Mozart by the composer Antonio Salieri in disguise, who plans to pass the composition off as his own when it is performed at Mozart’s funeral. But after Mozart dies, his wife Constanze tears the score from Salieri’s hands and locks it away. Funeral, burial, curtain – and the fate of the unfinished Requiem is left a mystery.

In reality, the Requiem was commissioned by a minor composer named Count Walsegg who wanted to pass it off as his own. It’s something Walsegg was apparently known for — he would commission a piece, then have a private concert for friends, claiming he wrote it. I imagine they humored him for the pre-concert schnitzel and schnapps.

Mozart did die before finishing the Requiem, and it’s then that the story gets interesting. Constanze solicits the help of Mozart’s friend Süssmayr and others in finishing the Requiem, then rushes it to publication and performance, carefully omitting the fact that Mozart didn’t write the whole thing.

She had good reason for the deception. Remember her line in the film, “Money just slips through his fingers, it’s ridiculous”? It was true. He’d left his family in dire financial straits, and she naturally wanted to maximize the income from his last composition. “Mass for the Dead Written by W.A. Mozart on His Deathbed” sells way more tickets than “Mass started by W.A. Mozart and Finished by Some Guys.”

But I have to think close listeners knew something was up when they heard it. The 14 movements of Mozart’s Requiem vary from breathtaking to meh. Even on the edge of the grave, Mozart would never have phoned in a tediosity like this:

0:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DpQoKW-1VbE” parameters=”start=7 end=33″ /]

That’s the Sanctus. There’s nothing wrong with it, which says it all. It’s just forgettable. And sure enough, it’s a Süssmayr.

The Sanctus is a checked box, a solid B. But the Lacrimosa movement was written by a whole different animal, namely Mozart. To see how Mozart mastered the details, I’ll focus on just the first eight beats of the Lacrimosa, and only one aspect of that brief passage.

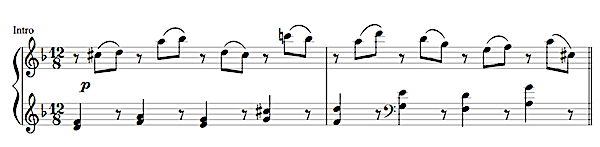

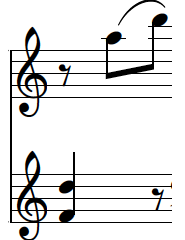

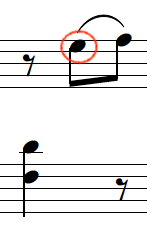

Lacrimosa (“Full of Tears”) is about the anguish of damned souls on the day of judgment. It opens with eight slow beats of three notes each — one low, answered by two high, like so:

0:12

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVRM56M61v8″ parameters=”end=12″ /]

There’s so much there to talk about, but I’ll stick to just one — the selection of pitches. If Süssmayr (or I) had written those bars using the same bass line, it might have sounded like this:

Each of those “sobs” is just…you know, fine. Nothing incorrect, every choice safe and normal. There’s little variety, partly because every note is a chord tone, meaning it belongs to the triad for that beat. As a result there’s very little dissonance, which is what tears are made of.

By contrast, Mozart’s sobs are full of yearning dissonance, and more often than not, that dissonance comes from non-harmonic tones — pitches foreign to the triad of the moment. For a D minor triad, for example, the chord tones are DFA, and if you play a G, that’s a non-harmonic tone. They usually fit one of 12 rules (patterns with the notes around them), which is how your ear makes sense of the pitch despite it being a chordal immigrant. I’ll eventually write more about these fantastic notes, but for now I want to show how the skilled use of non-harmonic tones helps to make Mozart Mozart.

I’ve isolated each of the eight sobs of the Lacrimosa below and slowed them down in brief audio clips so you can hear the non-harmonic tones (red circles).

Sob 1

Hear how the C# creates a searing tension before going up to the D? That’s a non-harmonic tone. In that faux Süssmayr clip above I changed it to an A, which is part of the triad, so there’s not much tension or interest. C# is better — it’s a non-harmonic tone called a displaced neighbor, and it aches against the low D before resolving upward.

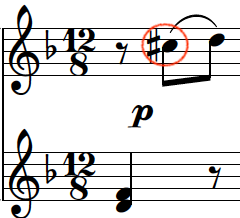

Sob 2

Sob 2 reverses the poles: the first note on the top line is in the chord and the second is the non-harmonic. This time the pattern is called an escape tone — a B♭ pops out the top, knocking boots with the As below.

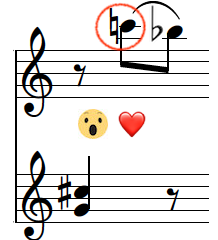

Sob 3

The D is an appoggiatura, my favorite non-harmonic, one I definitely don’t have to look up every single damn time I spell it. See how the eighth notes in Sob 1 are dissonant→consonant and in Sob 2 are consonant→dissonant? Even if you call both of the eighths in #3 chord tones, they are both dissonant against the lower notes, forming a 7th and a tritone respectively (the devil in music). And notice that we’ve now had three upper notes in a row that are dissonant, which builds the tension.

Sob 4

This is the one, oh my god, this is the beauty. Those bottom two notes form a tritone, G and C#, that’s nice. But the corker is the next one, that high C. I’ve written before about the melodic minor scale and the fact that the 7th note in the scale can be raised or lowered depending on whether the line is going up or down from there. But here you get both forms of the note at the same time — C# against C. Play that clip again. Combined with the tritone, it’s just achingly lovely, and the tension that’s been ratcheting up for the past two sobs reaches peak density.

Sob 5

Then right at the midpoint of the phrase, the tension is released: Sob 5 is all chord tones and an expressive leap up the the peak of the phrase, the high D. Now we’ll start tumbling down with the next sob.

Sob 6

This one’s a nice little crunch called a diminished triad. The E and B♭ form a tritone, the “devil in music” again. Looking ahead, you can see we’re in a tumbling pattern melodically — after climbing to that high D (Sob 5) we drop down in 6, small reach upward in 7, big fall in 8.

Sob 7

D against E is a 9th, an elegant clash. The E is a non-harmonic called a displaced passing tone. (I’ll write more about the twelve kinds of non-harmonic tones eventually — they are the spice.)

Sob 8

We’ve reached the cadence now, the harmonic punctuation at the end of a phrase, so nothing fancy here. It’s a half cadence, meaning it ends on an arrow pointing to our minor home, which is where the choir comes in. The sobs then continue under the entrance of the voices, unifying the emotion like a ground bass.

When you realize that this is a light analysis of one aspect of the first 12 seconds of one movement of one piece by Mozart, you can start to see why his music is playing in a hundred places around the world every minute of every day 250 years later, while poor Süssmayr’s Wikipedia page says, “Popular in his day, he is now known primarily as the composer who completed Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s unfinished Requiem.”

13. MOZART “Lacrimosa” from Requiem Mass (3:20)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVRM56M61v8″ /]

EXTRA CREDIT Four-pepper theorists will enjoy working out the Romans for 0:24-0:48. It is a four-bar harmonic master class.

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | 13 Mozart | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale on Facebook:

Dance of the Atonal Cowboy (Ginastera)

- July 16, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

7 min

#12 in Laney’s List

I spent most of my musical life unconvinced by atonal music (music without a key). I dutifully listened to all the landmarks of Schoenberg and Berg. I understood it and could analyze it and even compose atonally, but it just failed to reach me as a listener. Here’s a taste (16 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eAcZk9mE3tU” parameters=”start=44 end=60″ /]

DISLIKE.

It took me years to admit that I simply didn’t like (most) Schoenberg, that I didn’t find it effective as music. I’ve spent a lot of time among people for whom such a statement is evidence of a lack of sophistication, the confession of a triad-hugging simpleton. Whatever.

Schoenberg’s goal was the liberation of music from what he called “the tyranny of tonality,” setting it free from the tired clichés of key and chord and progression. I’m with him in spirit — by the end of the 19th century, Western music was running in some deep, exhausted ruts. But to my ear, Schoenberg took away too damn much. I couldn’t find the motives and shapes and repetitions that are also part of the narrative your ear follows. It’s not that they aren’t there in Schoenberg — do the analysis and you’ll find them. But I can’t perceive them as a listener in the ruins of tonality he keeps burning and re-burning.

Then…I discovered atonal music that WORKS, that friggin’ DELIGHTS me, throwing the tonal center out the window but keeping those other elements of motive and shape and repetition. Now two of my favorite pieces of music in the world — two of the pieces on Laney’s List — are atonal. You’re about to hear one of them.

The first time I heard “Danza del gaucho matrero” (Dance of the Arrogant Cowboy) from Danzas Argentinas by Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983) I was a music professor sitting in a student jury exam, the end-of-semester mini-recital required of all music performance majors. The performer was one of our top pianists. I was supposed to write something intelligent about her progress since the previous semester. Instead, I remember being so gobsmacked by the sounds coming out of the piano that I wrote nothing at all.

The movement starts with a dark, grumbling tangle of sound, low on the keyboard, forming no recognizable chords or key. But there is shape and repetition, flying by so fast you have to listen hard to catch it. Here are the first four measures, which are gone in 2.5 seconds:

Listen to just those 2.5 seconds:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9R4PrfFeQp4″ parameters=”start=1 end=5″ /]

Hear how he groups the notes in sixes, then extends to 12 the third time (blue arrow)?

DOOdle deedle deedle DOOdle deedle deedle

DOOdle deedle deedle deedle deedle deedle

Then it repeats, with a change:

DOOdle deedle deedle DOOdle deedle deedle

DOOdle deedle deedle doo POP! — POP!

(How’s that for sophistication?)

Then both repeat again, at which point we’re only 10 seconds in. At 0:12, a new figure repeats twice. At :15, another one, and at 0:19, another one. So you are on a runaway horse, and the atonality says there’s no home at the end of the trail, but the composer had the basic human decency to give you a saddle horn to hold on to — these fascinating, repeated rhythmic structures.

At 0:42 it becomes tonal! Kind of. Can a piece be both atonal and tonal? No, it cannot. Wait, there’s THIS one!

It continues galloping (because once you see “Dance of the Arrogant Cowboy,” there’s no other way to think of it) between tonal and atonal sections, but we never get thrown because Ginastera, you mad genius, you gay Argentine caballero, you gave us a saddle horn of repetition!

Listen.

12. GINASTERA “Dance of the Arrogant Cowboy” from Danzas Argentinas (2:57)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9R4PrfFeQp4″ /]

EXTRA CREDIT Just to show how repetition of elements can make even a wild atonal piece coherent, see if you can hear the mistake between 0:42 and 0:47. She misfires the first time, then nails the repetition. If atonal music was pure chaos, you wouldn’t be able to spot that.

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

A Velvet Revolution (Debussy, Afternoon of a Faun)

- June 27, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

12 min

#11 in Laney’s List

He was the most impressionistic composer of all time, but he didn’t like the label. I get that. A label becomes a pigeonhole that makes the audience assume what they will hear before they hear a note, and then (most aggravating of all) measure the result against that assumption. Add the fact that “impressionist” was first coined by a critic in 1874 as a mocking epithet, plus the fact that much of his work isn’t impressionistic at all, and you can see why he resisted it.

Prelude to ‘The Afternoon of a Faun’ by Claude Debussy (1862-1918) is a revolutionary piece. It’s been called the first truly modern composition, a claim I didn’t understand at first. It’s not angular or dissonant or rhythmically jarring like Stravinsky and Schoenberg. How can anything this smooth and elegant be modern?

But once you start taking it apart, holy cow.

It was written as a musical “prelude” to a Symbolist poem describing a faun (goat-man) drowsily recounting his conquests of nymphs as he lolls in a meadow. And just as Impressionistic painting uses muted colors, vague lines, and suggestions rather than statements, Debussy leans toward the muted tone colors of strings and woodwinds, quiet dynamics, and fragmentary melodies to blur the musical lines. That’s all interesting but not revolutionary.

It’s the harmony that points ahead to the 20th century. The opening gesture in the flute (0:30-0:40) starts out in No Key Whatsoever — just a sinewy mix of whole-tone and chromatic scales without a center. Then suddenly it snaps into focus with a clear outline of E major (0:40-0:48). Just as you adjust emotionally to this new home, the faun sprints away, and the harmony moves to B-flat (0:49-0:59). Here’s the thing: B-flat is literally the furthest you can get harmonically from E major. It’s another planet. It simply isn’t done, or (mostly) hadn’t been prior to this. It’s every bit as adventurous and unchained as Wagner, but because each line, each individual part in the orchestra is moving smoothly by step or half-step from chord to chord, the harmony itself can cross through intergalactic space without a bump because Debussy knows where the wormholes are.

This is a composer inviting you to trust him, to surrender to the music — then rewarding that surrender.

Seven spots:

- The silence at 0:58.

- The perfectly-executed swells at 1:54-2:19, and then the flute, and then the harp.

- 4:00 to that achingly beautiful transition at 4:38. Oh my god.

- 4:56. Normal chord, jazz chord, normal chord, jazz chord.

- The build to the horns at 5:21, and then THE HORNS AT 5:21.

- 5:29. Close your eyes and enjoy one of the most mesmerizing passages of music ever written. Hear how the flutes and strings seem to be following unrelated pulses? Wait, why are your eyes open??

- The unbearable yearning sweetness of the two violins at 7:50, and the 30 seconds that follow.

11. DEBUSSY Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (10:47)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jlLoXvamfZw” parameters=”start=27″ /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow me on Facebook…

The Tragic Silence of Lili Boulanger (Vieille Priére Bouddhique)

- June 18, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

Laney’s List #10 (11 min)

There is no shortage of composers whose lives and work were cut short by an early death: Chopin 39, Gershwin 38, Mozart 35, Schubert 31. We know those names because they managed through skill and luck to get a foothold on posterity before they died. It’s intriguing to wonder what Chopin or Gershwin would have been writing at 40 or 50 and heartbreaking to know we’ll never know. But at least we have what we have.

Now consider a composer with all the skill but who died so young that we are forced to wonder what she might have been creating at 30. Or 28. Or 25.

Lili Boulanger may be the best composer you’ve never heard of. Born in Paris in 1893, she showed early musical talent and quickly developed a unique and compelling style as a composer, full of innovative textures and harmony. At 19 she won the Prix de Rome, the highest French honor for composers, the first woman to win the award. With it came a five-year stipend to live and work in Rome, but her failing health brought her home early, and she died of intestinal tuberculosis at 24.

Her death didn’t just silence a great composer. It was a cruel foreclosure on what would have been the first extensive body of large-scale composition by a woman.

It’s hard to find a field as male-dominated as classical composition, and not because women somehow lack the gene. You need a very specific and intensive education to become a composer, something women were often denied. You need time, which for women often meant freedom from domestic responsibilities. And you need to have someone take you seriously enough to mentor your talent, sponsor your concerts, publish your work, and occasionally hand you an entire orchestra to play with.

The fact that women composers until recently often had names like Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Clara Schumann, and Alma Mahler hints at the way they managed to get any hearing at all. But even these remarkable talents were generally confined to small forms — solo piano, songs, trios — and endured other restrictions. Referring to her brother Felix, Fanny Mendelssohn’s father told her in a letter that “Music will perhaps become his profession, while for you it can and must be only an ornament.”

Even those who broke through to the larger forms often did so in a shadow. When Amy Beach wrote the first symphony by an American woman and had it premiered by the Boston Symphony in 1896, it was promoted as a symphony “by the wife of the celebrated Boston surgeon Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach.” The score, the parts, and the program listed her only as “Mrs. HHA Beach.” Her husband disallowed any formal study of composition or income from her work and limited her to two concerts a year so that she could “live according to his status, that is, function as a society matron and patron of the arts”[1]

Lili Boulanger had found her way past the hurdles and through the maze. She was writing large-scale works of surpassing strength and originality and receiving the accolades of a composer on the cusp of a brilliant career.

Then she was gone.

Vieille Priére Bouddhique (Old Buddhist Prayer) is a setting for solo tenor, choir, and orchestra. Listen to the whole piece, but for a particular taste of what we lost, note the astonishing echoic texture and shifting harmonies at 5:32-6:00.

10. BOULANGER Vieille Priére Bouddhique (8:34)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xF9SltYJAT8″ /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

Impossible Ravel (Alborada del Gracioso)

- June 16, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

16 min

Flavio~ CC BY 2.0

(#9 from Laney’s List)

Ifirst knew Ravel as the tightly-wound precisionist of Le Tombeau — then I heard this flaming swordfight of a piece.

He grew up in Basque country, 10 miles from Spain, and it shows here. “Alborada del Gracioso” (Morning Love Song of the Jester) started as a movement from a piano suite, but there’s no way a symphonic Jedi like Ravel was going to resist throwing this one to the orchestra.

I heard the orchestral version of “Alborada” first, and it took the top of my head off. For years it was my favorite piece by my favorite composer. Then I heard it had been written first for piano. This was like saying the rooftop dance scene from West Side Story was originally for finger puppets and slide whistle. Uh, no offense to the piano, somehow.

Then I heard the piano version, and it took me an hour to even FIND the top of my head.

Last time I started with the piano version of Tombeau, then orchestra. I’ll flip the script for this one. Note the triple-tonguing trumpet/horn/flute at 1:12-1:30, which (FYI) is not actually possible, then compare to the same impossible spot for piano.

RAVEL, “Alborada del Gracioso” from Miroirs (orch, 7:43)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=paDKkCEWx1g” /]

Now put the genie back in the bottle. This performance is insane. Listen through 1:30 at least, just to hear what human fingers can evidently do.

RAVEL, “Alborada del Gracioso” from Miroirs (piano, 6:22)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vykux_ms-P4″ /]

RELATED

RELATED

Ravel in Two Colors (Le Tombeau de Couperin)

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

Ravel in Two Colors (Le Tombeau de Couperin)

- June 13, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

9 min

(#8 from Laney’s List)

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) was meticulous. It’s hard to find a photo in which he’s not wearing a three-piece suit and pocket square, and his music is so tight it squeaks. He wrote slowly, sweating every detail, producing 85 compositions before he died at 62. Mozart by contrast wrote 626 pieces before dying at 35.

Ravel is sometimes lumped in with the Impressionists, and some of his work has that blurred, suggestive quality of impressionism. But more of it is crisp and linear, a return to elements of the style and form of Bach and Mozart that was eventually called Neoclassicism, pushing back against the dismantling of form and tonality by Schoenberg et al. I love and loathe the various fruits of that dismantling project, but for Ravel, I have nothing but love.

He was a stunning orchestrator and spent a great deal of time and energy rewriting piano compositions for orchestra. Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition is almost unknown in the piano original. What you’ve heard is Ravel’s brilliant orchestration of it. He also took the unusual step of orchestrating a number of pieces that he himself had first written for piano, including the piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917). The piece itself is a remembrance (tombeau) of the Baroque composer François Couperin, but each of the six movements is dedicated to the memory of a friend of Ravel’s who had died in the First World War, published as the war was still busily decimating a generation.

Here are two versions of a short Ravel piece side by side — the first movement of Ravel’s Tombeau for piano, then for orchestra.

RAVEL, “Prelude” from Le Tombeau de Couperin for piano (3:05)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uaCPY4Plg14″ /]

RAVEL, “Prelude” from Le Tombeau de Couperin for orchestra (3:30)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w5vKEjcv9OA” parameters=”start=60″ /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Ravel portrait by Véronique Fournier-Pouyet, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Click LIKE below to follow on Facebook…

What Is It About This Aria? (Delibes, Flower Duet)

- June 12, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

5 min

(#7 in the Laney’s List series — a music prof chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

I usually know why a piece of music slays me. It’s kind of my thing. But here’s a piece that I think is absolutely captivating, and I’m not entirely sure why that is.

Sure, I can find a captivating thing or three. The way the sopranos separate at the beginning of each measure, then join and rise together in thirds is an aural dance if ever there was, and 1:40-2:07 is some of the most elegant vocal writing I’ve ever heard. But I’m already sold by the time I get to 1:40, so that’s not it.

The chords are elegant and slightly nonstandard in that I’m-a-pretty-little-Frenchman way that makes me think of Satie at his Gymnopediest. If the second chord (1:10) had been V, for example, it would have been clunky and ordinary. Going to IV7 instead is just lovely. And the chord at 1:16, the one that ends the phrase! Instead of your average half cadence on V , he ends on iii. My keyboard is on the fritz (sorry, I mean on the françois) or I’d give you two sound files to show the difference. But just listen to that moment at 1:16 and see if you don’t hear a wistful harmonic lift-and-sigh in the strings. Nothing says This piece was built within ten years and ten kilometres of the Eiffel Tower like a phrase that ends on iii.

Still, I’m not convinced those details are the whole boule de cire. What do you think?

7. DELIBES “Flower Duet” from Lakmé (3:35)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C1ZL5AxmK_A” parameters=”start=63 end=148″ /]

See also: 1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | Full list | YouTube playlist

Look, It’s Just Cool (Reich Sextet)

- June 10, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

5 min

(#6 in the Laney’s List series — a music prof chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

Five composers especially haunt Laney’s List, coming back 3-4 times each. Four I could have predicted — Chopin, Bach, Mozart, Ravel. But until I started whittling, I didn’t know I’d give minimalist Steve Reich a trifecta as well.

Minimalism is the pendulum swing that followed the mid-20th century throwing-a-chair-while-barking school of it-is-totally-music-yuh-huh-is-so composition. It is mostly triads and conventional harmony, mostly simple patterns slowly changing over time, and represented a major palate cleanser after the avant garde of Varèse et al.

Terry Riley and Philip Glass are the emblematic pioneers of minimalism. But just as it’s Chopin representing the nocturne in this list, not Irish composer and nocturne inventor John “Who?” Field, so Reich is my go-to for minimalism. And in this list, like a good minimalist, he repeats.

Minimalism is not for everyone, so I’m starting in the relative shallows — a short interior movement of Reich’s Sextet for four percussionists and two pianos (1985). No major analysis required — it’s just cool. Things I love:

- The great contrast between those dense, massive hits of mixed dry and wet sound and that telegraphic vibraphone.

- The surprisingly chill melodic figure in the vibes at 0:26, like a ring tone interrupting General Patton’s speech.

- The way those two characters interact for the rest of the short movement.

I think nearly everything Reich does is interesting and cool, but I know it’s not for everyone. That’s why I’ve included three pieces of his in the list, increasing in conceptual difficulty. As Germany can tell you, sometimes it takes three Reichs to know they just aren’t your thing.

REICH, “Slow” from Sextet

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbTZdEnu2yo” /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Chopin Had Just One Request (Impromptu No. 4)

- June 07, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

6 min

(#5 in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

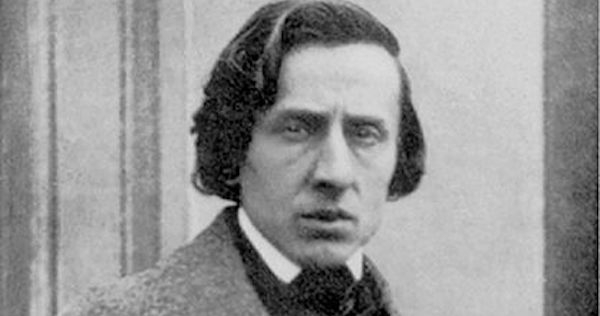

If Chopin had his way, you wouldn’t know his Impromptu No. 4. Written in 1834 when he was 24 years old, it was not published until he was 45, by which time he had stopped writing new works entirely, having been dead for six years.

He had asked nicely that his unpublished works (including this one) remain unpublished after his death, which seems reasonable. But Posterity invoked the legal principle quid facietis in hac — roughly, What are you going to do about it? — and published anyway. It is now among his most performed pieces.

It starts with the fantastic agitated energy of his etudes, then goes into a tranquil melody that he clearly borrowed from the Judy Garland song “I’m Always Chasing Rainbows.”

Enjoy.

CHOPIN, Impromptu No. 4 (4:50)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UplCACM5MC0″ /]

See also: 1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow me on Facebook: