the pbb freebeebee

- January 16, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In Parenting, PBB

5

5

Yes, I’m aware that I’m posting like mad, right after warning that I’d be posting like sane from now on. But there’s news!

I’ve worked out a new plan with the company that is hosting the web seminars — one that will reduce my costs by a good bit. So we here at PBB International are passing the savings on to you!

The PBB Book Club meetings (Jan 27-Feb 2) will now be free of charge. I just finished refunding the fees to those of you who were already registered. The topical webinars (beginning Feb 17) will still include the $18 fee, so feel free to transfer your refund over to one of those. Or send out for pizza! The choice is yours. But the pizza, of course, is less enlightening and more fattening.

Registration for the book clubs is still limited to fifteen each, and one has already closed, so if you want to join us, hurry up and put your name in the goblet!

the heartbreak of all-done

- January 09, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In death, My kids, Parenting, reviews

10

10

Last year a client asked me to look over a rhyming children’s book she’d written. It was cute as a bug, but something wasn’t quite right. I picked one page and read it over and over. At last it hit me: it had ambiguous feet.

As opposed to this…

Left foot, left foot, right foot, right.

Feet in the day

Feet in the night.

There’s only one way to read that — the way Dr. Seuss wanted you to. He was a master of metrical feet — repeating patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables — which opened up children’s literature in a way we take for granted now. He saved us from Dick and Jane. Seuss is so perfectly metered that you can’t say it wrong.

A federal judge inadvertently proved the point last September when he tried, and failed, to imitate Seuss in a ruling from the bench. The judge had received a hard-boiled egg in the mail from a prison inmate protesting his diet, then declined the inmate’s request for an injunction, as follows:

I do not like eggs in the file

I do not like them in any style.

I will not take them fried or boiled

I will not take them poached or broiled.

I will not take them soft or scrambled

Despite an argument well-rambled.No fan I am of the egg at hand.

Destroy that egg! Today! Today!

Today I say! Without delay!

He screws the pooch in the second line, inserting an extra syllable (“in”), then again in the transition from “scrambled” to “despite.” And the last stanza is pure embarrassment. Did this judge sleep through the day in law school when they covered iambic tetrameter?

The point! The point! The point! The point!

Could you, would you, like the point?

My youngest daughter is on a Seussian bender lately. We’ve been alternating The Lorax and Oh The Places You’ll Go! for weeks — two of his four greatest (the others are Horton Hears a Who and the Grinch. Spare me The Cat in the Hat.)

We were in the middle of Oh, The Places You’ll Go! last week:

You’ll look up and down streets. Look ’em over with care.

About some you will say, “I don’t choose to go there.”

With your head full of brains and your shoes full of feet,

you’re too smart to go down any not-so-good street.And you may not find any you’ll want to go down.

In that case, of course, you’ll head straight out of town.It’s opener there, in the wide open air.

Out there things can happen and frequently do

to people as brainy and footsy as you.

Erin (9): Is he still alive?

Dad: Who?

Erin: Dr. Seuss.

Dad: Oh. No, he died about fifteen years ago, I think. But he had a good long life first.

And when things start to happen,

don’t worry buy viagra pills online uk. Don’t stew.

Just go right along.

You’ll start happening too.OH! THE PLACES YOU’LL GO!

I suddenly became aware that Delaney (6) was very quietly sobbing.

Dad: Oh, sweetie, what’s the matter?

Delaney: Is anybody taking his place?

Dad: What do you mean, punkin?

Delaney: Is anybody taking Dr. Seuss’ place to write his books? (Begins a deep cry.) Because I love them so much, I don’t want him to be all-done!

I hugged her tightly and started giving every lame comfort I could muster — well, everything short of “I’m sure he’s in Heaven writing Revenge of the Lorax.”

I scanned the list of Seuss books on the back cover. “Hey, you know what?” I said. “We haven’t even read half of his books yet!”

Feeble, I know. So did she.

“But we will read them all!” she said. “And then there won’t be any more!” I had only moved the target, which didn’t solve the problem in the least.

In addition to “paleontologist, archaeologist, and marine biologist,” Laney wants to be a writer. I seized on this, telling her she could be the next Dr. Seuss. She liked that idea quite a bit, and we finished the book. The next day she was at work on a story called “What Do I Sound Like?” about a girl who didn’t know her own voice because she had never spoken.

My instinct whenever one of my kids cries — espcially that deep, sincere, wounded cry — is to get them happy again. This once entailed nothing more than putting something on my head — anything would do — at which point laughter would replace tears. It’s a bit harder once they’re older and, instead of skinned knees, they are saddened by the limitations imposed by mortality on the people they love.

But is “getting them happy again” the right goal?

I’m often asked in interviews how I help my children accept death without the afterlife. Accept it?! Hell, I don’t accept it! People who “accept” death tend to fly planes into buildings. To think that I can or even should blunt that sadness too much is a suspect idea. Yet too often, I try.

Death is immensely sad, even as it makes life more precious. It’s supposed to be. So I shouldn’t be too quick to put something on my head or dream up a consolation every time my kids encounter the sadness of mortality. Sometimes it’s good to let them think about what it means that Dr. Seuss is all-done, and to cry that deep, sincere, heartbreaking cry.

Thinking by Example: guest column by Stu Tanquist

Thinking by Example

By Stu Tanquist

contributing author, Parenting Beyond Belief

(This column also appears in the current (Jan 4, 2008) issue of Humanist Network News.)

We want our children to make wise choices. We hope they will follow our example and use good “common sense.” But when it comes to our own mental faculties, are we really as competent as we presume? And more importantly, what kind of example are we really setting for our kids?

Most people have just one way of enhancing their reasoning skills – the school of hard knocks. We make good choices and bad choices, learn from our decisions and move on. Though vital to our success and survival, this hit-and-miss approach is fraught with peril. Can you really afford to be wrong when considering an alternative cancer therapy or a belief system that compels you to sacrifice countless hours and thousands of dollars? Clearly the school of hard knocks is not a reliable solution, for we could invest a good portion of our lives making one giant mistake, or even bring about our untimely demise.

Strangely, few people make a serious intentional effort to improve their own reasoning skills, and are therefore less capable of helping their children do the same. For many, the solution is to seek a good education and embrace lifelong learning, but is that a trustworthy choice?

You can earn graduate degrees from accredited and respected universities in disciplines that are grounded in nonsense. They appear impressively scientific, yet rely on magical thinking rather than legitimate scientific method and strong credible evidence. If the material you learn is not true, have you really gained knowledge? Philosophers overwhelmingly say no, and for good reason. But even so, increasing your knowledge is only part of the equation. Rather than blindly believing whatever we are told, we need good reasoning skills to determine how much confidence to place in any given truth claim.

How then does one improve his or her ability to reason? The first step is to get grounded by understanding where we are prone to error. If we appreciate our innate fallibility we are less prone to accept and maintain beliefs with unfounded confidence. Let’s try a quick assessment. On a blank sheet of paper, write your answers to the following questions:

-

• Why do scientists consider anecdotes (personal experience such as seeing, hearing, etc.) to be mostly useless as a form of evidence?

• What biases do all humans possess that make us prone to believing false claims as true?

• What logical fallacies (common errors in reasoning) can you name and effectively explain to others?

If you are like most people, there is still a lot of white space on that sheet of paper indicating that there is room for additional understanding.

Consider the following analogy. Imagine that a computer has been designed to give you advice that could have an enormous positive or negative impact on the quality of your life. How confident would you be in its answers if you knew that it had serious flaws and was frequently prone to error? Most of us would have strong reservations, yet we implicitly trust our own flawed minds.

Simply stated, we are much more fallible than we intuitively presume

ourselves to be – a time tested recipe for error. It’s called being human.

________________________________

Cognitive scientists seem endlessly entertained by exposing the myriad of ways in which our thoughts and actions are misguided. Simply stated, we are much more fallible than we intuitively presume ourselves to be – a time tested recipe for error. It’s called being human.

Though humbling, this simple reality need not be depressing. Yes we are prone to error, but with intentional effort we can significantly enhance our reasoning skills. While we may not ever match wits with the wisest of the wise, we can all improve the hand that was dealt to us by our genetics, environment and experience. For greater understanding, the following books offer a great start.

- • How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life by Thomas Gilovich

• How to Think About Weird Things: Critical Thinking for a New Age by Theodore Schick and Lewis Vaughn

• Attacking Faulty Reasoning: A Practical Guide to Fallacy-Free Arguments by T. Edward Damer

If our goal is to help our children make wise choices, then let’s start by setting a good example. Anyone can model the school of hard knocks. It takes humility and integrity to seriously consider and strive to overcome our own limitations, but the process can be deeply rewarding. Your kids are not the only ones who will benefit.

__________________________

Stu Tanquist is a self-employed trainer, seminar leader and instructional designer with over 20 years of experience in the learning and development industry. His employment history ranges from working as an emergency paramedic to serving as a strategic-level director for learning and development. A long time student of logic and reasoning, Stu holds three degrees. He authored the essay “Choosing Your Battles” in Parenting Beyond Belief.

PBB online seminars!

Registration is now open for the Parenting Beyond Belief Online Seminars and I’m giddy about it. Here’s the blurb:

THE PARENTING BEYOND BELIEF ONLINE SEMINARS

hosted by Dale McGowan, editor/co-author, Parenting Beyond Belief

Join author Dale McGowan and other nonreligious parents for these fun and informative web events: The PBB Book Club and the PBB Webinars. Information and registration links below.

The Parenting Beyond Belief Online Book Club

One-hour online discussions led by Dale McGowan, author/editor of Parenting Beyond Belief: On Raising Ethical, Caring Kids Without Religion

Join Dale for a live discussion and Q&A about the book Parenting Beyond Belief: On Raising Ethical, Caring Kids Without Religion, the first comprehensive resource for parenting without religion.

Dale describes the process of bringing this groundbreaking book from concept to release, as well as the consensus that emerged from the book’s 25 contributors on how to raise great kids without religion. The floor is then open for questions from the participants.

To facilitate the Q&A, registration for each one-hour Book Club meeting is limited to 15 participants.

Registration is FREE OF CHARGE, and you do NOT have to have read the book to listen in! Click on the date of your choice to register:

Sunday, January 27 at noon Eastern

Monday, January 28 at 9:00 pm Eastern [REGISTRATION CLOSED]

Tuesday, January 29 at 9:00 pm Eastern [REGISTRATION CLOSED]

Wednesday, January 30 at 9:00 pm Eastern [REGISTRATION CLOSED]

Thursday, January 31 at 9:00 pm Eastern

Friday, February 1 at 9:00 pm Eastern

Saturday, February 2 at 3:00 pm Eastern

The Parenting Beyond Belief Webinars

Dale McGowan, author/editor of Parenting Beyond Belief: On Raising Ethical, Caring Kids Without Religion, hosts a five-part series of online seminars (or “webinars”) addressing the central issues of parenting without religion.

Registered participants log in to a provided website at the allotted time, then dial a provided phone number for the session audio. During each one-hour webinar, presenters can submit questions online, of which Dale will answer as many as time allows.

Each topic is offered twice in a given week, once on Sunday and again on Tuesday, with identical content. Participants can sign up for any number or combination of topics in the five-part series. Registration for each webinar is $18.

______________

WEBINAR #1: Secular Family, Religious World

Register for Sunday Feb 17 at noon Eastern, or Tuesday Feb 19 at 9 pm Eastern

I often find myself saying I’ve “set religion aside.” Actually, that’s a bit like saying someone who rides a bike to work has set traffic aside. I’m still in it, still surrounded by it, and always will be. One of our jobs as secular parents is to help our kids learn to co-exist with religion, even as they engage and challenge religious beliefs and their effects.

This seminar explores issues of secular parenting in a religious world, including

- -Helping kids to be religiously literate without indoctrination;

-Dealing with church-state separation issues in schools;

-Helping kids respond to the idea of hell and pressures from religious friends;

-Hopeful signs for secular parents in the United States.

______________

WEBINAR #2: The Religious Extended Family

Register for Sunday Feb 24 at noon Eastern, or Tuesday Feb 26 at 9 pm Eastern

Most nonreligious parents are raising their children within a religious extended family. This can provide enriching diversity but also painful conflict: “Should we just go to church to satisfy Grandma?” “Should we have the kids baptized to keep the peace?” “How can I tell Aunt Ruth it’s not okay to proselytize my son?”

This seminar looks at ways to minimize conflict, resolve disputes, and turn seemingly unbridgeable gaps into benefits for the entire extended family.

______________

WEBINAR #3: The Art of the Question

Register for Sunday March 2 at noon Eastern, or Tuesday March 4 at 9 pm Eastern

Wondering and questioning are at the heart of naturalistic parenting. This seminar explores ways in which secular parents can use the pivotal moment of the question to build an environment of boundless wonder and fearless inquiry for their children.

______________

WEBINAR #4: Raising Naturally Ethical Kids

Register for Sunday March 9 at noon Eastern, or Tuesday March 11 at 9 pm Eastern

Morality isn’t magic. It is, and has always been, based in reason. Understanding the reasons to be good can move children beyond simplistic rule-following to the development of active moral judgment—a far more reliable ethical foundation.

This seminar describes the difference between commandments and principles and offers tips for encouraging children to be actively involved in their own moral development.

______________

WEBINAR #5: Death and Life

Register for Sunday March 16 at noon Eastern, or Tuesday March 18 at 9 pm Eastern

The single most significant and profound thing about our existence is that it ends, rivaled only by the fact that it begins. Death is a hard thing to grasp, let alone accept. Religious notions of an afterlife are of little real help—believers cling just as frantically to life, grieve just as bitterly its end, and have the added burden of worrying about hell.

This seminar presents practical ways to help children begin a healthy and satisfying lifelong contemplation of mortality, using the Inversion Principle and the Improbability principle to flip the whole equation on its head. A healthy understanding of death can help our children envision life itself in an entirely new way—one that religion cannot hope to match for pure, astonished joy.

fearthought

I’m up to my eyebrows in background reading for the sequel to Parenting Beyond Belief (possible names: Still Parenting Beyond Belief; Parenting Beyonder Belief; and Parenting Beyond Belief: The Empire Strikes Back). Likely release date is around December ’08.

In addition to reading huge amounts of useful stuff, I’m doing a bit of reading on the other side of the fence: religious parenting books. Some are very good, like the work of Christian parenting author Dr. William Sears. Some are mixed, including (to my admitted surprise) James Dobson, who serves up some quite sound advice along with his nonsense. Then there’s complete lunacy and even unintentional self-parody, for which we turn to author and televangelist Joyce Meyer.

fearthought

Joyce Meyer

Here’s a passage from Meyer’s “Helping Your Kids Win the Battle in their Mind“:

Satan will look for your child’s weakest area and attack at that point. He will attempt to fill your child with worry, reasoning, fear, depression and discouraging negative thoughts.

Don’t laugh at what she’s placed between worry and fear in the devil’s toolkit unless you turn straight to tears. According to her website, Joyce Meyer (who lives, interestingly, about three miles from my parents) has television and radio programs in “over 200 countries” — a truly remarkable achievement on a planet with 195 countries. Slightly less amusing is the fact that she has sold over a million copies of a book for which this passage can serve as an encapsulation:

I once asked the Lord why so many people are confused and He said to me, ‘Tell them to stop trying to figure everything out, and they will stop being confused.’ I have found it to be absolutely true. Reasoning and confusion go together.

from Battlefield of the Mind, p. 99

Last year she issued a version of Battlefield of the Mind “For Teens,” which I’m reading at the moment.

You can tell it’s intended for teens because of the cool dripping paint on the front cover, and the use of words like “wanna” and “gonna” and phrases like “where your head is at” (which teenagers use all the time, along with “groovy” and “hang ten.” If nothing else, Joyce is clearly hep to the jive.) My favorite sentence: “If you’re like most teens, you’ve probably seen the movie The Karate Kid.” Karate Kid was released in 1984, several years before today’s teenagers were born.

Fewer giggles were forthcoming from passages like this:

I was totally confused about everything, and I didn’t know why. One thing that added to my confusion was too much reasoning.

That’s right: it comes back again and again in her advice, in millions of books and throughout her broadcasting empire. Don’t even start thinking. Most troubling of all is the desperate attempt to make kids fear their own thoughts, right at the age they are supposed to be challenging and questioning in order to become autonomous adults:

Ask yourself, continually, “WWJT?” [What Would Jesus Think?] Remember, if He wouldn’t think about something, you shouldn’t either….By keeping continual watch over your thoughts, you can ensure that no damaging enemy thoughts creep into your mind.

I will defend to the death her right to put these opinions out there, and the rights of her millions of devoted readers to read it and to think it is something other than sad, ignorant, unethical, fearful sheepmaking. I’m just all the more motivated to put out a message precisely opposed to Meyer’s fearthought, one that advocates building up critical thinking and moral judgment in tandem, then inviting ideas into your head without fear that one of them will somehow jump you when you’re not looking.

Now I just need a word for the opposite of fearthought. I’m sure one will occur to me.

Freethought

This excerpt from a post of mine last June (“Rubbernecking at Evil”) shows how different are the planets Joyce Meyer and I occupy — even beyond the number of countries. Compare the bolded passage below with Joyce Meyer’s advice:

About a year ago, [my daughter Erin, then 8] went through a brief period of self-recrimination, literally dissolving into tears at bedtime, but uncharacteristically unwilling to discuss it. The morning after one such nighttime session, we were lying on the trampoline together, looking at the sky, and I asked if she would tell me what was troubling her. “Did you do something you feel bad about, or hurt somebody’s feelings at school?” I asked. “There’s always a way to fix that, you know.”

“No,” she said. “It isn’t something I did.”

“Something somebody else did? Did somebody hurt your feelings?”

“No.” A long silence. I watched the clouds for awhile, knowing it would come.

At last she spoke. “It isn’t anything I did. It’s something…I thought.”

I turned to look at her. She was crying again.

“Something you thought? What is it, B?”

“I don’t want to say.”

“That’s OK, you don’t have to say. But what’s the problem with thinking this thing?”

“It’s more than one thing.” She looked at me with a worried forehead. “It’s bad thoughts. I think about saying things or doing things that are bad. Like…”

I waited.

“Like bad words. That’s one thing.”

“You want to say bad words?”

“NO!!” she said, horrified. “I don’t at ALL!! But I can’t get my brain to stop thinking about this word I heard somebody say at school. It’s a really nasty word and I don’t like it. But it keeps popping into my brain, no matter what I do, and it makes me feel really, really bad!!”

She cried harder, and I hugged her. “Listen to me, B. You are never bad just for thinking about something. Never.”

“What? But…If it’s bad to say a bad word, then it’s bad to think it!”

“But how can you decide whether it’s bad if you don’t even let yourself think it?”

She stopped crying in a single wet inhale, and furrowed her brow. “Then…It’s OK to think bad things?”

“Yes. It is. It’s fine. Erin, you can’t stop your brain from thinking – especially a huge brain like yours. And you’ll make yourself crazy if you even try.”

“That’s what I’m doing! I’m making myself crazy!”

“Well don’t. Listen to me now.” We went forehead to forehead. “It is never bad to think something. You have permission to think about everything in the world. What comes after thinking is deciding whether to keep that thought or to throw it away. That’s called your judgment. A lot of times it’s wrong to act on certain thoughts, but it is never, ever wrong to let yourself think them.” I pointed to her head. “That’s your courtroom in there, and you’re the judge.”

The next morning she woke up excitedly and gave me a high-speed hug. Once she had permission to think the bad word, she said, it just went away. She was genuinely relieved.

Imagine if instead I had saddled her with traditional ideas of mind-policing, the insane practice of paralyzing guilt for what you cannot control – your very thoughts. Instead, I taught her what freethought really means.

I’m more than a little proud of myself for managing to say the right thing. That’s always a minor miracle. I don’t blog about the three hundred or so times in-between that I say the wrong thing.

In the year since that day, Erin has several times mentioned that moment, sitting on the trampoline, as the single best thing I ever did for her. As with most such moments, I had no idea at the time that I was giving her anything beyond the moment itself. I just wanted her to stop crying, to stop beating up on herself. But in the process, it seems, I genuinely set her free.

Elv(e)s Lives!

ERIN (9): No, they don’t.

DELANEY (6): Yes, they do!

ERIN: Laney, they don’t.

DELANEY: They do!

It was my girls in their bedroom on the first day of Christmas break, (damned) early in the morning, apparently engaged in Socratic discourse. Let’s listen in from the hall:

ERIN: They do not.

DELANEY: They do so.

ERIN: Laney, there’s no way they come alive.

DELANEY: I know they come alive, Erin!

I walked in.

DAD: Morning, burlies!

GIRLS: Hi Daddy.

DAD: What’s the topic?

ERIN: Laney thinks the elves really come alive.

DELANEY, pleadingly: They do! I know it!

I didn’t have to ask what elves they were on about. It’s apparently an extremely old or very new tradition here in Georgia — I’m new in town and wouldn’t know which. Kids buy little stuffed elves and place them somewhere at night before they go to sleep. In the morning, the elf, having come to life in the night, is somewhere new.

ERIN: How do you “know” it, Laney?

DELANEY: Because. I just do.

ERIN: What’s your evidence?

(Oooooooo, the old evidence gambit! This should be good.)

DELANEY: Because it moves!

ERIN: Couldn’t somebody have moved it? Like the Mom or Dad?

DELANEY: But [cousin] Melanie’s elf was up in the chandelier! Moms and Dads can’t reach that high.

ERIN: Oh, but the elf can climb that high?

(Pause.)

DELANEY: They fly.

ERIN: Oh jeez, Laney.

DELANEY: Plus all the kids on the bus believe they come alive! And all the kids in my class! (Looks at me, eyebrows raised.) That’s a lot of kids.

So how to handle a thing like this? I want to encourage both critical thinking and fantasy. Fortunately Erin wasn’t being snotty or rude. Her tone was relatively gentle. As a result, Laney was not getting overly upset by the inquiry – just mildly defensive.

Erin finally looked at me and said in a half-voice: “I don’t want to ruin her fun, but…”

“You’re both doing a great job,” I interrupted. “This is a really cool question and you’re trying to figure it out! You’re asking each other for reasons and giving your own reasons, then you try to think of what makes the most sense—I love that!”

They both beamed.

“The nice thing is that you don’t have to agree.” (Celebrate diversity and all that. Only the Monolith is to be feared.) “You listened to each other and hashed it out. Now you can think about it on your own and decide, and even change your mind a million times if you want.”

I say that last line all the time. The invitation to change your mind knowing you can freely change it back makes it less threatening to test out alternatives. If you don’t like a new hypothesis, go back to your first one. It’ll still be there. That permission makes for more flexible thinking.

I also try to make the point that no one else can change your mind for you. You should always find out what other people think, but you don’t have to worry that they will reach in and change your mind without your consent. It’s amazing how powerful that simple idea is. In the end, only you can throw that switch and change your mind, so wander on through the marketplace of ideas without fear.

So they let it go. Erin got practice at gentle persuasion, and a little critical seed was planted in Laney’s mind, along with the invitation to hang on to the fantasy as long as she damn well pleases. When her love affair with reality becomes so well-developed that knowing the truth is more important to her than thinking stuffed elves come to life, she’ll happily move on. But just as in other areas of belief involving dead things coming to life when no one is looking, I want her to make decisions under her own power.

So they let it go. Erin got practice at gentle persuasion, and a little critical seed was planted in Laney’s mind, along with the invitation to hang on to the fantasy as long as she damn well pleases. When her love affair with reality becomes so well-developed that knowing the truth is more important to her than thinking stuffed elves come to life, she’ll happily move on. But just as in other areas of belief involving dead things coming to life when no one is looking, I want her to make decisions under her own power.

branch-on-ground

Acacia tree at sunset, Laikipia Plateau, Kenya

DELANEY (6, after ten silent seconds staring at our bathroom scale): I wonder how people in places like Africa and India weigh themselves if they don’t have scales.

DAD: Hm. I never even thought about that. Any ideas?

(Five seconds pass.)

DELANEY: I know! They could sit on a long tree branch and see how far down it bends.

DAD (recombing his hair): Holy cow, Lane. That would totally work.

ERIN (9): And they could say, “‘I weigh branch-halfway-down. How about you?’ And the other guy says, ‘I ate too much. I weigh branch-on-ground.'”

(Laughter.)

DELANEY: Or they could put carvings on the tree trunk to see how far down it goes.

This kid slays me on a daily basis. She recognized a problem, proposed a workable solution, and refined it, all within sixty seconds. I’m pretty sure that my own scientific investigations at the age of six were limited to which nostril produced the best-tasting boogers.1

___________________________

1Left side, by a mile — though further research is necessary.

strange maps

- December 07, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, Parenting, reviews, wonder

7

7

Please cancel my appointments for the rest of the month, take the phone off the hook, and don’t expect another blog entry until spring. I have found the website of my dreams and am going to live there for awhile. Someone please pay my rent, feed my children and satisfy my wife until I return.

Maps absorb me like a…what’s something really absorbent…like a sponge-like thing. In England I pored over the incredible Ordnance Survey maps for hours at a time.

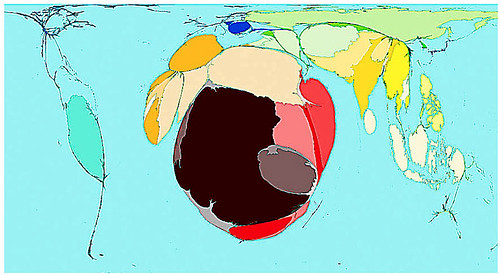

I’ve always particularly loved the paradigm rattlers, like this

which makes the point that a Northerly orientation is arbitrary, having been selected, by the most astonishing coincidence, by Northern Hemisphereans, who apparently like it on top.

I was 18 when I first saw Joel Garreau’s “Nine Nations of North America” concept, from the book of the same name:

Now I’ve found a blog called STRANGE MAPS, and I have no further need of the outside world. In addition to the above, there are maps to compare the relative wealth of nations today

and comparisons throughout time:

Deaths in war since 1945:

There is a map of US states renamed for countries with similar GDPs:

how the world would be if all the land were water and all the water land:

and what it’ll look like in 250 million years:

…all with intelligent commentary and links. I’ve only scratched the surface. There’s Europe if the Nazis had won. A map of the United States from the Japanese point of view. A map of the U.S. with the former territories of Indian nations overlaid. World transit systems drawn as a global world transit map in the style of the London Underground. A color-coded map of blondeness in Europe and of kissing habits in France.

Plop a child of a certain type and age (about 10-16) in front of Strange Maps (or another called Worldmapper, where the resized world maps originate) and don’t expect a response when you call ’em for dinner. I can’t wait for my boy to get home.

natural generosity

[Written for Humanist Network News, December 5, 2007.]

One of the sanest, surest, and most generous joys of life comes from being happy over the good fortune of others.

Robert A. Heinlein

Who can resist the impulse to feel all gushy and reflective at this time of year? It’s no coincidence that holidays emphasizing family and charity and peace and goodwill are sprinkled through the shortest, coldest days of the year when, by golly, we’d better have each other to turn to if we’re going to make it through. Charity is naturally born in such a season, and just about everyone gladly succumbs to the best of human impulses.

One of the parental challenges of the season is to encourage impulses like generosity and discourage selfishness, greed, and insane materialism in our children. Christians try to keep their kids focused on Jesus as “the reason for the season,” or ask them to imitate what has been called God’s “supernatural generosity.” That’s fine, I suppose, but it’s hardly necessary. Secular parents should have no difficulty encouraging perfectly natural generosity. The secret is to simply let kids be generous.

The best thing about the phrase “it’s better to give than to receive” is that it’s actually true—especially for kids. Receiving is all too familiar to them. They are constantly in the receiving role. We give them food, clothing, and everything else they need. But give kids a chance to step outside the receiving role and experience the satisfaction of being the generous one, and they vibrate with excitement. They feel grown up. It empowers them.

The best thing about the phrase “it’s better to give than to receive”

is that it’s actually true—especially for kids.

______________________________

Generosity is absolutely addicting. But to really drive the lessons home for kids, you have to make the experience their own.

Suppose your child’s school has a canned food drive for the local food shelf. Many well-meaning parents put a few extra cans in the cart during their regular shopping, then hand the cans to the kids to bring to school. It’s a good start, but the kids don’t really feel directly active in that process. They are just the link between Mom’s purchase and the school’s drive.

If instead you want them to genuinely feel the addicting “generosity buzz,” it’s best to involve them at each step. Drive them to the store, then have them take it from there.

Let the child decide how much to spend, and if at all possible, let her use her own money. The difference between Dad’s $5 and her own $5 is the difference between helping Dad be generous and being generous herself. One is passive; the other is active and addictive. Don’t even add your money to hers. Make two separate contributions if you wish.

Schools will generally provide a list of acceptable items. Let your kids go up and down the aisles and pick out the food themselves—then watch their posture the next morning as they leave the front door for school carrying bags of their own generosity.

No need to wait for school food drives, of course—your local food shelf is always happy to benefits from generosity lessons! Charities can also provide specifics about who receives donations and the difference that donations make for families in need, which helps kids to connect their giving to those who benefit.

It’s also crucial to detach generosity from external rewards. Neither schools nor parents should offer incentives for generosity, or that incentive becomes the goal. In the process, the feeling of genuine generosity is almost completely lost.

The same goes for gift giving. Try not to buy gifts for your children to give to others. Involve them in the thoughtful selection or making of gifts for friends and relatives.

Again, when it comes to gifts, we’re not working from scratch. Children love opening presents, but they are generally much more excited when someone else is opening a gift from them—especially if it’s a gift they made, or picked out and paid for, themselves.

Another good practice is to encourage children to divide their allowance or other money into three jars. No, not Jesus—Others—Yourself, but you’re close: it’s Spending, Saving, and Giving. Let the child decide how to divide the money, but let them know that something should go into each jar every time they receive money. You’ll be surprised at how their natural generosity shows up in that giving jar—especially if they’ve had the experience of active, addictive giving.

It goes without saying that there’s no better lesson for kids than seeing generosity – of time, of money, of kindness, of spirit – demonstrated firsthand by Mom and Dad. The buzz of generosity is not only addicting—it’s downright contagious.

_______________________

Parents: Looking for a non-sectarian organization to support? Consider the United Nations Childrens Fund (UNICEF), a tremendously effective organization improving the lives of children worldwide.

on borrowed memes and missed compliments

You may have seen the article in TIME Magazine about the weekly children’s program at the Humanist Community in Palo Alto, California:

On Sunday mornings, most parents who don’t believe in the Christian God, or any god at all, are probably making brunch or cheering at their kids’ soccer game, or running errands or, with luck, sleeping in. Without religion, there’s no need for church, right?

Maybe. But some nonbelievers are beginning to think they might need something for their children. “When you have kids,” says Julie Willey, a design engineer, “you start to notice that your co-workers or friends have church groups to help teach their kids values and to be able to lean on.” So every week, Willey, who was raised Buddhist and says she has never believed in God, and her husband pack their four kids into their blue minivan and head to the Humanist Community Center in Palo Alto, Calif., for atheist Sunday school.

All in all a positive piece about what seems to be a lovely program by a very strong and positive group of folks. Very few wincers in the article.

It’s unfortunate but predictable that the response in many fundamentalist religious blogs has been jeering and mockery. Albert Mohler (president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) called it an “awkward irony.” Others have claimed that the fact that atheists spend so much time denying God is “proof that God exists,” or found the idea otherwise worthy of contempt.

I’ve looked in vain (so far,anyway — please help me out) for a Christian blog that says what I think is obvious, and what is essentially stated in the article itself: that this represents an enormous compliment from secular humanism to Christianity. Systematic values education for children is something they’ve developed much more successfully than we have. And for good reason: they’ve had a lot more time, centuries of development and refinement. We humanists have always attended to the values education of our kids, of course, but until quite recently it has mostly taken place at the family level. When it comes to values education in the context of our worldview community, Christians have had more practice. In the past generation, such efforts as UU Religious Education, Ethical Culture, and the Humanist Community program have begun closing that gap in the humanist infrastructure.

One of the most marvelous and successful programs in the world is the Humanist Confirmation program in Norway. According to the website of the Norwegian Humanist Association, ten thousand fifteen-year-old Norwegians each spring “go through a course where they discuss life stances and world religions, ethics and human sexuality, human rights and civic duties. At the end of the course the participants receive a diploma at a ceremony including music, poetry and speeches.” They are thereby confirmed not into atheism, but into the humanist values that underlie all aspects of civil society, including religion.

HUMANIST ORDINANDS IN NORWAY,

SPRING 2007

All of these secular efforts at values education can be seen as an evolution of religious practices, opening conversations about values and ethics while working hard to avoid forcing children into a preselected worldview before they are old enough to make their own choice. And though the practices themselves often have religious roots, the values themselves are human and transcend any single expression.

Instead of mocking and jeering, I’d like to see Christians recognize and accept these adaptations as genuine compliments. Perhaps the first step is for humanists to say, clearly, that they are meant as compliments. I can’t speak for the Humanist Community, nor for the Norwegian Humanists, but I can speak for Parenting Beyond Belief. The Preface notes that

Religion has much to offer parents: an established community, a pre-defined set of values, a common lexicon and symbology, rites of passage, a means of engendering wonder, comforting answers to the big questions, and consoling explanations to ease experiences of hardship and loss.

Just as early Christians recognized the power and effectiveness of the Persian savior myths and borrowed them to energize the story of Jesus, there are currently things that Christians do much better than we do. I’m preparing a post on that very topic. We should not be shy about considering their experiments part of the Grand Human Experiment, setting aside the things that don’t work, with a firm NO THANKS, then borrowing those things that work well, and saying THANK YOU — much louder and more sincerely than we have done.