Ahh…you never forget your first meme

(Two serious posts already this week! Who’s up for some Friday blog candy?)

————————–

The first time my kids saw our family photo on the back of Parenting Beyond Belief in a bookstore, they were elated. “We’re famous!” Erin squealed.

“Yes,” Laney replied, “but the quiet kind of famous.”

She had once said she wanted to be “one of those famous people on the magazine covers.” Becca replied that it might be fun in some ways, but you also lose your privacy, and everyone watches and talks about everything you do. “I still think that would be fun,” Laney insisted.

So we began narrating her every move: “She’s picking up her spoon. Why is she holding her hand that way? Ooh, she glared at our cameraman. What does she have to be angry about? Do you think Delaney McGowan is losing her mind? Take our online poll!”

“Aaahhh, okay okay okay!! I don’t want to be that kind of famous,” she said. “I want to do something famous, but nobody knows I’m the person who did it.” She searched for the right word. “I want to be the quiet kind of famous.”

My first brush with the quiet kind of famous was in 1977. It was a thrilling year for me. I turned fourteen. I kissed Kathy Myerson on the lips. And I got myself published.

It was a single sentence, but it was published in a no-kidding book that was carried in all the best cheesy paperback bookracks in every checkout line in America. The title was Murphy’s Law, Book 2: more reasons why things go wrong!, with the word “wrong” upside down. Get it?? High-larious!

I’d read the prequel — Murphy’s Law—and Other Reasons Things Go Wrong! stem to stern a dozen times the year before. I loved it:

Parkinson’s Law

Work expands to fill the time available for its completion.The Law of Margarine Attraction

The odds of a piece of buttered bread landing butter-side down are directly proportional to the cost of the carpet.Boob’s Law

You always find something in the last place you look.

I can just hear my zitty little self snickering: “Heh heh. Boobs.”

Not until the seventh or eighth time through did I see the invitation on the final page:

Do you have a law that explains why things go wrong? Send it to the following address, and who knows—you might find your idea in the next edition of MURPHY’S LAW!

My head tipped back and drool collected, Homer-like, at the corners of my mouth. Fame, aggghghhhh…

For two solid weeks I read Murphy’s Law again and again, absorbing the basic rhythm and cynical logic of the jokes. Most were in the form conditional, comma, punch. And the punch has the zing of Comic Truth. Got it.

I started looking for Comic Truths everywhere I went. School? No—plenty of comedy, plenty of truth, but never, it seemed, in combination. Home was too familiar. I wasn’t sure what I was looking for, but I watched for that rhythm and logic in Fred Flintstone, Speed Racer, Carol Burnett, the Professor and Mary Ann. Nothing rang the bell.

I was prepared to give it up when my mother dragged me with her to the Sears women’s department. I sat in emasculated agony outside the dressing room as she tried on several hundred skirts and blouses. A sign atop a nearby rack of clothes caught my bored eye. “ALL DRESSES ON THIS RACK UNDER $50,” it said.

“Pfft,” I thought. “If it says ‘under $50,’ you know it isn’t $19.95.”

I sat up with a shock of recognition. It was cynical. It was rhythmic. Conditional, comma, punch! I had my Law!

I tinkered with the name for a week, coming up at last with “McGowan’s Madison Avenue Axiom,” then wordsmithed the phrasing a bit. Finally I typed “If an item is advertised as ‘under $50,’ you can be damn sure it isn’t $19.95” and sent it in. Four to six weeks later, I had my answer.

I was in!

They had discreetly removed the word “damn,” but it was otherwise unchanged. My free copy arrived in the mail later that year, just weeks after I planted one on Kathy. I was published.

Thirty years passed, during which other stuff surely happened—until one afternoon in late 2007 when the words “Murphy’s Law” caught my eye in the corner of a website. I had become 44 years old and a writer of additional sentences, even whole paragraphs, in the interim. And though Kathy Myerson occasionally surfaced in the soup of memory, I hadn’t thought about my one-sentence publishing debut since the Carter Administration.

I decided on a lark to Google the name of my long-ago law. Everything seems to leave a footprint somewhere on line, even if it happened before there was an “online.” Sure enough, there was a footprint—and another, and another. And another. “McGowan’s Madison Avenue Axiom” appeared by name on over 200 sites. The phrase “you can bet it’s not $19.95” is on about 350. It is fortune cookie filler. It’s on websites of one-liners. (I always wondered who came up with those. Turns out it’s me.) People use it as a signature line in advertising discussion forums. It serves as text filler for forum spammers.

It has morphed into “McGowan’s Christmas Shopping Axiom” in, for some reason, Australia, France, and the Netherlands.

The dollar amounts sometimes change (“If an item is advertised as ‘under $40’, you can bet it’s not $9.95”) as do the manners (“If an item is advertised as ‘under $50’, you can bet your ass it’s not $19.95”).

It appears in the 26th (get it??) anniversary edition of the original book.

My favorite of all was seeing it quoted as the opening line in the Washington Post Bridge column just a few months earlier.

Okay then. I’ve mastered the quiet kind of famous. Now to work on the rich kind.

Where all roads lead (2)

[Back to Part 1]

We’d had the conversation before, but this time a new dawning crossed Laney’s face.

“Sweetie, what is it?” I asked.

She began the deep, aching cry that accompanies her saddest realizations, and sobbed:

“I don’t want to die.”

Now let’s freeze this tableau for a moment and make a few things clear. The first is that I love this child so much I would throw myself under Pat Robertson for her. She’s one of just four people whose health and happiness are vital to my own. When she is sad, I want to make her happy. It’s one of the simplest equations in my life.

I say such obvious things because it is often assumed that nonreligious parents respond to their children’s fears of death by saying, in essence, Suck it up, worm food. When one early reviewer of Parenting Beyond Belief implied that that was the book’s approach, I tore him a new one. I am convinced that there are real comforts to be found in a naturalistic view of death, that our mortality lends a new preciousness to life, and that it is not just more truthful but more humane and more loving to introduce the concept of a life that truly ends than it is to proffer an immortality their inquiring minds will have to painfully discard later.

But all my smiling confidence threatens to dissolve under the tears of my children.

“I know, punkin,” I said, cradling her head as she convulsed with sobs. “Nobody wants to die. I sure don’t. But you know what? First you get to live for a hundred years. Think about that. You’ll be older than Great-Grandma Huey!”

It’s a cheap opening gambit. It worked the last time we had this conversation, when Laney was four.

Not this time.

“But it will come,” she said, hiffing. “Even if it’s a long way away, it will come, and I don’t want it to! I want to stay alive!”

I took a deep breath. “I know,” I said. “It’s such a strange thing to think about. Sometimes it scares me. But you know what? Whenever I’m scared of dying, I remember that being scared means I’m not understanding it right.”

She stopped hiffing and looked at me. “I don’t get it.”

“Well what do you think being dead is like?”

She thought for a minute. “It’s like you’re all still and it’s dark forever.”

A chill went down my spine. She had described my childhood image of death precisely. When I pictured myself dead, it was me-floating-in-darkness-forever. It’s the most awful thing I can imagine. Hell would be better than an eternal, mute, insensate limbo.

“That’s how I think of it sometimes too. And that frrrrreaks me out! But that’s not how it is.”

“But how do you know?” she asked pleadingly. “How do you know what it’s like?”

“Because I’ve already been there.”

“What! Haha! No you haven’t!”

“Yes I have, and so have you.”

“What? No I haven’t.”

“After I die, I will be nowhere. I won’t be floating in darkness. There will be no Dale McGowan, right?”

“And millions of worms will eat your body!!” chirped Erin, unhelpfully.

“…”

“Well they will.”

“Uh…yeah. But I won’t care because I won’t be there.”

“Still.”

I turned back to her sister. “So a hundred years from now, I won’t be anywhere, right?”

“I guess so.”

“Okay. Now where was I a hundred years ago? Before I was born?”

“Where were you? You weren’t anywhere.”

“And was I afraid?”

“No, becau…OMIGOSH, IT’S THE SAME!!”

It hit both girls at the same instant. They bolted upright with looks of astonishment.

“Yep, it’s exactly the same. There’s no difference at all between not existing before you were born and not existing after you die. None. So if you weren’t scared then, you shouldn’t be scared about going back to it. I still get scared sometimes because I forget that. But then I try to really understand it again and I feel much better.”

The crisis was over, but they clearly wanted to keep going.

“You know something else I like to think about?” I asked. “I think about the egg that came down into my mommy’s tummy right before me. And the one before that, and before that. All of those people never even got a chance to exist, and they never will. There are billions and trillions of people who never even got a chance to be here. But I made it! I get a chance to be alive and playing and laughing and dancing and burping and farting…”

(Brief intermission for laughter and sound effects.)

“I could have just not existed forever — but instead, I get to be alive for a hundred years! And you too! Woohoo! We made it!”

“Omigosh,” Laney said, staring into space. “I’m like…the luckiest thing ever.”

“Exactly. So sometimes when I start to complain because it doesn’t last forever, I picture all those people who never existed telling me, ‘Hey, wait a minute. At least you got a chance. Don’t be piggy.'”

More sound effects, more laughter.

Coming to grips with mortality is a lifelong process, one that ebbs and flows for me, as I know it will for them. Delaney was perfectly fine going to sleep that night, and fine the next morning, and the morning after that. It will catch up to her again, but every time it comes it will be more familiar and potentially less frightening. We’ll talk about the other consolations — that every bit of you came from the stars and will return to the stars, the peaceful symphony of endorphins that usually accompanies dying, and so on. If all goes well, her head start may help her come up with new consolations to share with the rest of us.

In his brilliant classic The Tangled Wing, Emory psychologist Melvin Konner notes that “from age three to five [children] consider [death] reversible, resembling a journey or sleep. After six they view it as a fact of life but a very remote one” (p. 369). Though rates of development vary, Konner places the first true grasp of the finality and universality of death around age ten—a realization that includes the first dawning deep awareness that it applies to them as well. So grappling with the concept early, before we are paralyzed by the fear of it, can go a long way toward fending off that fear in the long run.

In his brilliant classic The Tangled Wing, Emory psychologist Melvin Konner notes that “from age three to five [children] consider [death] reversible, resembling a journey or sleep. After six they view it as a fact of life but a very remote one” (p. 369). Though rates of development vary, Konner places the first true grasp of the finality and universality of death around age ten—a realization that includes the first dawning deep awareness that it applies to them as well. So grappling with the concept early, before we are paralyzed by the fear of it, can go a long way toward fending off that fear in the long run.

Laney, for better and worse, is ahead of the curve. All I can do is keep reminding her, and myself, that knowing and understanding something helps tame our fears. It may not completely feed the bulldog — the fear is too deeply ingrained to ever go completely — but it’s a bigger, better Milk-Bone than anything else we have.

Where all roads lead (1)

I have 22 posts jostling for attention at the moment, but a Saturday night conversation with my girls has sent all other topics back to the green room for a smoke.

The three of us were lying on my bed, looking at the ceiling and talking about the day. “Dad, I have to tell you a thing. Promise you won’t get mad,” said Delaney (6), giving me the blinky doe eyes. “Promise?”

“Oh jeez, Laney, so dramatic,” said Erin, pot-to-kettlishly.

“I plan to be furious,” I said. “Out with it.”

“Okay, fine. I…I kind of got into a God fight in the cafeteria yesterday.”

I pictured children barricaded behind overturned cafeteria tables, lobbing Buddha-shaped meatballs, Flying Spaghetti Monsters, and Jesus tortillas at each other. A high-pitched voice off-camera shouts Allahu akbar!

“What’s a ‘God fight’?”

“Well I asked Courtney if she could come over on Sunday, and she said, ‘No, my family will be in church of course.’ And I said oh, what church do you go to? And she said she didn’t know, and she asked what church we go to. And I said we don’t go to church, and she said ‘Don’t you believe in God?’, and I said no, but I’m still thinking about it, and she said ‘But you HAVE to go to church and you HAVE to believe in God,” and I said no you don’t, different people can believe different things.”

Regular readers will recognize this as an almost letter-perfect transcript of a conversation Laney had with another friend last October.

I asked if the two of them were yelling or getting upset with each other. “No,” she said, “we were just talking.”

“Then I wouldn’t call it a fight. You were having a conversation about cool and interesting things.”

Delaney: Then Courtney said, ‘But if there isn’t a God, then how did the whole world and trees and people get made so perfect?’

Dad: Ooo, good question. What’d you say?

Delaney: I said, ‘But why did he make the murderers? And the bees with stingers? And the scorpions?’

Now I don’t know about you, but I doubt my first grade table banter rose to quite this level. Courtney had opened with the argument from design. Delaney countered with the argument from evil.

Delaney: But then I started wondering about how the world did get made. Do the scientists know?

I described Big Bang theory to her, something we had somehow never covered. Erin filled in the gaps with what she remembered from our own talk, that “gravity made the stars start burning,” and “the earth used to be all lava, and it cooled down.”

Laney was nodding, but her eyes were distant. “That’s cool,” she said at last. “But what made the bang happen in the first place?”

Connor had asked that exact question when he was five. I was so thrilled at the time that I wrote it into his fictional counterpart in my novel Calling Bernadette’s Bluff:

“Dad, how did the whole universe get made?”

Okay now. Teachable moment, Jack, don’t screw it up. “Well it’s like this. A long time ago – so long ago you wouldn’t even believe it – there was nothing anywhere but black space. And in the middle of all that nothing, there was all the world and the planets and stars and sun and everything all mashed into a tiny, tiny little ball, smaller than you could even see. And all of a sudden BOOOOOOOM!! The little ball exploded out and made the whole universe and the world and everything. Isn’t that amazing!”

Beat, beat, and…action. “Why did it do that? What made it explode?”

“Well, that’s a good question. Maybe it was just packed in so tight that it had to explode.”

“Maybe?” His forehead wrinkles. “So you mean nobody knows?”

“That’s right. Nobody knows for sure. “

“I don’t like that.”

“Well, you can become a scientist and help figure it out.”

“…”

“…”

“Dad, is God pretend?”

“Well, some people think he’s pretend and other people think he’s real.”

“How ’bout Jesus?”

“Well, he was probably a real guy for sure, one way or the other.”

Pause. “Well, we might never know if God is real, ’cause he’s up in the sky. But we can figure out if Jesus is real, ’cause he lived on the ground.”

“You’re way ahead of most people.”

“Uh huh. Dad?”

“Yeah, Con.”

“Would you still love me if all my boogers were squirtin’ out at you?” Pushes up the tip of his nose for maximum verité.

“No, Con, that’d pretty much tear it. Out you’d go.”

“I bet not.”

“Just try me.”

I told Laney the same thing—that we don’t know what caused the whole thing to start. “But some people think God did it,” I added.

She nodded.

“The only problem with that,” I said, “is that if God made everything, then who…”

“Oh my gosh!” Erin interrupted. “WHO MADE GOD?! I never thought of that!”

“Maybe another God made that God,” Laney offered.

“Maybe so, b…”

“OH WAIT!” she said. “Wait! But then who made THAT God? OMIGOSH!”

They giggled with excitement at their abilities. I can’t begin to describe how these moments move me. At ages six and ten, my girls had heard and rejected the cosmological (“First Cause”) argument within 30 seconds, using the same reasoning Bertrand Russell described in Why I Am Not a Christian:

I for a long time accepted the argument of the First Cause, until one day, at the age of eighteen, I read John Stuart Mill’s Autobiography, and I there found this sentence: “My father taught me that the question ‘Who made me?’ cannot be answered, since it immediately suggests the further question ‘Who made god?’” That very simple sentence showed me, as I still think, the fallacy in the argument of the First Cause. If everything must have a cause, then God must have a cause.

…and Russell in turn was describing Mill, as a child, discovering the same thing. I doubt that Mill’s father was less moved than I am by the realization that confident claims of “obviousness,” even when swathed in polysyllables and Latin, often have foundations so rotten that they can be neutered by thoughtful children.

There was more to come. Both girls sat up and barked excited questions and answers. We somehow ended up on Buddha, then reincarnation, then evolution, and the fact that we are literally related to trees, grass, squirrels, mosses, butterflies and blue whales.

It was an incredible freewheeling conversation I will never, ever forget. It led, as all honest roads eventually do, to the fact that everything that lives also dies. We’d had the conversation before, but this time a new dawning crossed Laney’s face.

“Sweetie, what is it?” I asked.

She began the deep, aching cry that accompanies her saddest realizations, and sobbed:

“I don’t want to die.”

Welcome to the World on PBS

The PBS series Religion & Ethics Newsweekly ran a nice segment on August 15 about the nonreligious baby naming ceremony I co-hosted at last September’s convention of Atheist Alliance International. The guests of honor were Lyra and Sophia Cherry, two-year-old twin daughters of Shannon and Matt Cherry (director of the Institute for Humanist Studies at the time). Several prominent freethinkers participated, including Richard Dawkins.

The ceremony itself was very well conceived, with readings, gifts, music, rich symbolism, a choked-up dad, and the pledging of mentors for each of the girls.

Matt wrote a lovely and thoughtful column about the event for On Faith, a site sponsored by the Washington Post and Newsweek. (Read the column here, and if you find yourself enveloped in a warm feeling about humanity when you finish it, do not go on to read the extremely depressing comment thread.)

The brief PBS video segment is here. Don’t blink and you’ll see and hear someone the script calls “UNIDENTIFIED MAN #1.” Hey Ma, c’est moi!

More on secular celebrations, including the complete script of the Cherry event, is here.

The Facelift

Welcome to the facelifted Meming of Life!

In addition to several minor tweaks (font color, title style, no more mysterious pseudo-Masonic MW&R logo, author mug, etc), I wanted a banner.

I’ve had a thaaang for Canadian artist Glendon Mellow’s beautiful blog The Flying Trilobite since I discovered it last summer. It’s awash with examples of its subtitle—Art in Awe of Science—which is why, when I wanted a banner for The Meming of Life, I turned immediately to Mr. Mellow.

As you can see from the incredible oil painting at the top, Glendon did NOT disappoint.

Glendon has posted a piece about the evolution of the banner on The Flying Trilobite, complete with early sketches, so I won’t go into that side of things too much. Suffice it to say that I gave poor Glendon almost no guidance whatsoever. And thank Thor for that! He immediately came up with four great ideas, two of which ended up combined in this rich and complex image.

I am deeply smitten with images that have multiple meanings. My publisher, for example, could not have pleased me more with the cover design for Parenting Beyond Belief (see sidebar). I’ll try to describe the layers of significance the banner has for me.

The basic narrative is this: A Neolithic parent’s careful painting of an aurochs is echoed in the child’s imitation. Satisfied with their work, parent and child walked off together across the beach.

Ahh, but then there are the layers of meaning for me:

> ANTHROPOLOGY and CULTURE

As an anthro major at UC Berkeley, I was gobsmacked by the opportunity to connect with individual human beings across 16,000 years through the paintings at Lascaux. The paintings represent one of oldest surviving expressions of human experience captured in a meme, or unit of culture—and is therefore an early example of the “meming” of life.

> PHILOSOPHY

Evokes Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, which raises questions about reality, illusion, and the human willingness to be deceived.

> MY OWN IRRATIONALITY

I am terrified of cows. You herd me. I think Glendon knew this, somehow, and felt I should see one every time I went to my own damn blog.

|

> FOOTPRINTS

In addition to the parenting metaphor, two sets of footprints side by side are a simultaneous allusion to (1) the incredible 3.7 million year old hominid footprints at Laetoli in East Africa, which were excavated in part by my first anthropology professor, Tim White; AND (2) the sappy glurge “Footprints” ( “It was then that I carried you” ) which in turn never fails to remind me of the chokingly hilarious point-counterpoint version in The Onion.

> HUMOR

In addition to the hidden Onion reminder, the child’s Far-Side-like cow completely cracks me up.

> THE OCEAN

I’ve always loved this ocean metaphor of Isaac Newton’s–a nice metaphor for the humility of science properly conceived:

I do not know what I may appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

The ocean also represents the POO (point of origin) for all life, including the aurochs/cow, the humans, the moss dangling at the entrance.

> PARENTING

Older than science, religion, art and culture.

I could go on. I’m just thrilled with it. Undying thanks to Glendon. Now go see his blog. Just remember to come back.

[HEY! If you haven’t read Becca’s second post, scroll down. It was bumped after a day and a half by the facelift, but it’s a must-read.]

Looking back…and it’s about time (2 of 2)

Guest column by Becca McGowan

I don’t think there is a God; but I wish there was one.

There it is. I said it.

I had never actually said this to anyone until my seven-year-old daughter asked me point-blank, “Mom, do you believe in God?” It had been easy to avoid a concrete answer up to that point because virtually all religious conversations in our home were between Dale and the kids. I was content to listen during family discussions and participate only in the easy parts: Everybody believes different things…the bible is filled with stories that teach people…we should learn about other people’s beliefs…we should keep asking questions so we can decide what we think…those were the easy parts. I told myself that I was still thinking about it.

The problem is that deep down, I had already decided. And I had decided that God was not real. God was created from the human desire to explain what we didn’t understand. God was an always-supportive father figure, able to get us through difficult times when human fathers were insufficient. I now believed what I had only toyed with in Mr. Tresize’s high school mythology class: A thousand years from now, people will look back on our times and say, “Look, back then the Christian myth held that there was one God and that his son became man…”

But wait a minute! This can’t be! Did I actually say this out loud to my daughter?! I am a GOOD person. I am a KIND person. I help OTHERS. As I left for school each day as a little girl, my mother always said, “Remember, you are a Christian young lady.” That’s who I AM!

Now, here I was, a mother, encouraging my children to keep asking questions, keep reading, keep talking with others. I want my children to think and learn. Then, I tell them, decide for yourself.

But had I ever asked questions about religion? Had I ever read about religion or talked with others? Had I actually decided for myself? No. I became a church-attending Christian as a way to rebel against my stepfather. I hadn’t thought about it for a day in my life.

Flash back eight years, driving home from church in our minivan, when Dale said to me, “I just can’t go to church anymore.” I was devastated.

I continued to attend church on my own for a couple of years. I also began reading Karen Armstrong’s In the Beginning. And I began to think about why I believed. The more I read and talked and debated, the more I realized that my belief was based on my label as a “Christian young lady.” My belief was based on uniting with my mother against my stepfather.

I now consider myself a secular humanist, someone who believes that there is no supernatural power and that as humans, we have to rely on one another for support, encouragement and love. Looking at religious ideas and asking questions, thinking and talking and then finally coming to the realization that I was a secular humanist—that was not the difficult part. Breaking away from the expectations and dysfunctions of my family of origin has proven to be the real and ongoing challenge.

__________________

BECCA McGOWAN is a first grade teacher. She holds a BA in Psychology from UC Berkeley and a graduate teaching certificate from UCLA. She lives with her husband Dale and three children in Atlanta, Georgia.

the legend of squishsquish

“Can I read you something from my Monster Museum book?”

I said sure, not knowing that we were launching a mini-obsession that so far has lasted a week. Delaney (6) flipped to the back of the book, which offers a short “bio” of each monster mentioned in the bad kiddie poetry that fills the rest of the book.

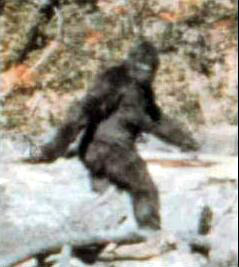

“‘BIGFOOT,’” she read. “‘Called Squishsquish in North America…’ Squishsquish?”

“Oh. Sasquatch.”

“You know about Bigfoot?” she asked, mighty impressed.

“A little,” I said. “Keep going. I want to hear.”

“‘Called Sasquatch in North America and Yeti in Asia. A huge, hairy, shy creature. Bigfoot prefers mountains, valleys, and cool weather. Many people claim to have seen and even photographed Squish…Squishkatch or Yeti or his footprints, but so far, no one has had a conversation with him.’ Haha! That’s funny.”

Each biographical entry has a little cartoon picture of the beast in question, with the exception of Bigfoot. We apparently know what a banshee looks like, and The Blob, and a poltergeist. But when it comes to Bigfoot, they simply put a question mark. I’m willing to bet it was the question mark that drew her attention to Bigfoot.

“If people took pictures,” she asked, “why is there a question mark?”

“I don’t know.”

“So is he real?”

“Some people think so, and some people think it’s a fake. Wanna see the pictures?”

We Googled up a few choice photos. Delaney gasped, launching into an enthralled monologue as I took furtive notes:

“It would be so interesting if Bigfoot was real. I really wonder if he is. It would be so cool if he was real! But maybe the picture is somebody in a gorilla suit. And maybe somebody went out with a big footprint maker and made footprints in the woods. Or maybe it’s real. But I’ll bet if he is real, he’s nice.”

“Why?”

“Because if he was mean, he’d be attacking people, and then we’d know he exists! But…there can’t be a person that big in a costume, so it seems like he has to be real somehow. Even the tallest person isn’t that tall.”

“So do you think it’s probably real, or probably not?”

She paused and thunk. “I’m not sure. I’m really, really not sure. I’ll bet scientists are trying to figure out. It’s just so cool to think about. It makes you curious.”

Yesterday she had a friend over—the pseudonymous Kaylee of a long-ago post—and dove right into the quest as I quietly transcribed the conversation on my laptop:

DELANEY: Have you ever heard of Bigfoot?

KAYLEE: No. What’s Bigfoot?

D: You have got to see this. You have got to see this. [Types BIGFOOT into Google.] Look, there it is. It’s called Bigfoot, but some people say Squishsquish.

K: What is it?!

D, with didactic precision: Some people say it’s like a gorilla man who lives in the forest. But you don’t have to worry. He wouldn’t be in any forest near us. Some people think it’s not even real.

K: So that’s Bigfoot??

D: Well it’s a picture.

K: So Bigfoot is real!

D: Nope, we don’t know that for sure. (Reads from website.) “An appeal to protect Bigfoot as an in-danger species has also been made to the U.S. Congress.”

K, (reading ahead): Look, it says right here, “Bigfoot is not real.” So he’s not real.

D: But we don’t know for sure. That’s just what the person says who has that website. That doesn’t make it for sure.

[Laney switches to image search, pulling up a full page of yetis.]

K: I hope it isn’t real. That would be so scary.

D: I hope it is. It would be so cool!

K: (looking at one photo): Does he only live in snow?

D: No look, there are pictures with no snow. It seems like he would hibernate. I wonder what he would eat.

K: Probably people.

D: I just wonder everything about him. Doesn’t it just make you so curious?

K: No. It makes me freaky.

I have a favorite particular moment in that dialogue–I’ll let you guess. But my favorite thing overall is Laney’s Saganistic approach to knowledge. Just as Carl Sagan wanted more than anything for intelligent life to exist elsewhere in the universe, Laney really wants Bigfoot to be real. It would, in both cases, be “so cool.” But that has no effect on her belief, or his, that the beloved possibility is real. Neither can see much joy or point in pretending that a wish makes it so. Both are happy to wait for the much greater thrill of knowledge, of the discovery that something wonderful turns out to be not just cool, but true.

On waking the heck up

To be awake is to be alive. I have never met a man who was quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?

From Walden by Henry David Thoreau

I was interviewed Tuesday for the satellite radio program “About Our Kids,” a production of Doctor Radio and the NYU Child Study Center, on the topic of Children and Spirituality. Also on the program was the editor of Beliefnet, whom I irritated only once that I could tell. Heh.

“Spirituality” has wildly different meanings to different people. When a Christian friend asked several years ago how we achieved spirituality in our home without religion, I asked if she would first define the term as she understood it.

“Well…spirituality,” she said. “You know—having a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and accepting him into your life as Lord and Savior.”

Erp. Yes, doing that without religion would be a neat trick.

So when the interviewer asked me if children need spirituality, I said sure, but offered a more helpful definition—one that doesn’t exclude 91 percent of the people who have ever lived. Spirituality is about being awake. It’s the attempt to transcend the mundane, sleepwalking experience of life we all fall into, to tap into the wonder of being a conscious and grateful thing in the midst of an astonishing universe. It doesn’t require religion. Religion can, in fact, and often does, blunt our awareness by substituting false (and dare I say inferior) wonders for real ones. It’s a fine joke on ourselves that most of what we call spirituality is actually about putting ourselves to sleep.

For maximum clarity, instead of “spiritual but not religious,” those so inclined could say “not religious–just awake.”

I didn’t say all that on the program, of course. That’s just between you, me, and the Internet. But I did offer as an example my children’s fascination with personal improbability – thinking about the billions of things that had to go just so for them to exist – and contrasted it with predestinationism, the idea that God works it all out for us, something most orthodox traditions embrace in one way or another. Personal improbability has transported my kids out of the everyday more than anything else so far.

Evolution is another. Taking a walk in woods over which you have been granted dominion is one kind of spirituality, I guess. But I find walking among squirrels, mosses, and redwoods that are my literal relatives to be a bit more foundation-rattling.

Another world-shaker is mortality itself, about which another small series soon. Mortality is often presented as a problem for the nonreligious, but in terms of rocking my world, it’s more of a solution. Spirituality is about transforming your perspective, transcending the everyday, right? One of my most profound ongoing “spiritual” influences is the lifelong contemplation of my life’s limits, the fact that it won’t go on forever. That fact grabs me by the collar and lifts me out of traffic more effectively than any religious idea I’ve ever heard. A different spiritual meat, to be sure, but no less powerful.

The program will air Friday August 8, 8-10am Eastern Time (US) on SIRIUS Satellite Channel 114—or listen online at Doctor Radio.

[BONUS QUESTION: Did you yawn when you saw the baby?]

the mix

You’ve got to be taught, before it’s too late

Before you are six or seven or eight

To hate all the people your relatives hate

You’ve got to be carefully taught

____________________

From the musical South Pacific

Explain to me if you will why I wrote this post, then tabled it for ten days, then paused over the delete key before finally posting.

Our three summer family reunions were terrific, especially for the kids, who have discovered or re-discovered no fewer than 50 cousins of various degrees of remove. Better yet, these cousins are good kids, enjoyable kids, funny and friendly and loving kids.

And ohhh so very religious. Which is fine, of course.

Becca and I are the dolphins in the tuna nets of our respective families. Most all of the relations on all three sides are not only churchgoing but fish-wearingly, abstinence-swearingly, cross-bearingly so. The fact that most of them are also genuinely delightful to be around — funny and friendly and loving — serves as a nice slap on my wrist any time I find myself lumping together all things and people religious.

How can I not love it when my twelve-year-old second cousin, working on a leather bracelet, asks, “Mister Dale, how do you spell ‘Colossians’?” (I nailed it.) Or when Becca, watching another young cousin making a wooden picture frame with the letters JIMS across the top, innocently asked, “Is that for sombody named Jim?” only to be told patiently that “it stands for ‘Jesus Is My Savior’.” It’s sweet. It’s lovely. Creepy-lovely, perhaps…but that’s a kind of lovely, isn’t it?

When it comes to assessing the many conservative religious folks in my life, though, there’s a complication, one that still makes me dizzy after all these years. It was captured by (of all people) Larry Flynt, who wrote in the LA Times about his unlikely friendship with Jerry Falwell after the televangelist’s death last year:

My mother always told me that no matter how repugnant you find a person, when you meet them face to face you will always find something about them to like. The more I got to know Falwell, the more I began to see that his public portrayals were caricatures of himself. There was a dichotomy between the real Falwell and the one he showed the public.

The same weird dichotomy is present in many of the deeply religious folks I know. Many are just plain good in word and deed, and I love having their influence in my kids’ lives. But many others, including some I like so much I could burst, will be in the midst of a perfectly normal conversation, then suddenly spew bile or rank ignorance — often without changing expression — before turning back to the weather or the casserole.

It’s not a case of some believers being lovely and others being nasty. That I could sort out. It’s much more confusing. Like Larry said of Jerry, they’re often the same people. But in the case of folks I know, it reveals itself in the opposite order of Flynt’s description. I liked them from the beginning, then was blindsided by the nastiness.

The conversation at one reunion found its way to gays and lesbians, and a cousin — one of my favorites, a deeply religious college graduate and the pick of the litter — suddenly said, “What kills me is when they say [homosexuality] shouldn’t be treated. Well if that’s the case, why treat schizophrenia? Why treat cancer?”

All heads nodded but mine. I was searching for the perfect line. Finally it came. “And what about the lefthanders?” I said. “And those got-dam redheads, roaming the streets untreated!”

They laughed, not quite getting it, and the topic quickly moved on to (if I remember correctly) boat motors.

I find myself related by blood or marriage to several ministers, including a couple who are among my favorite people on Earth, open and honest and deeply humane, without a shred of pretense. There’s another of whom I’m very fond as well, but in him we encounter The Mix. A quickish wit, he spends most of his time trying to make other people laugh. But when the conversation turned to the war and someone had the gall to mention the deaths of innocent civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan, he erupted:

“Oh innocent civilians, innocent bystanders, boo hoo! First of all, they’re not so innocent. Second of all, this is war! If you are my enemy, I’m not gonna shoot you in the leg, I’m not gonna shoot you in the arm…I’m going to put one right between your eyes. I’m going to annihilate you. And the sooner I do it, the sooner the world will be safe for God’s people.”

Several kids were sitting in earshot, getting themselves carefully taught. I was livid. “Now there’s a man of God!’ I said. “Hallelujah!”

Beloved Relation looked me in the eye, momentarily wordless, then decided to play it for comedy. “Just like the old days!” he bellowed. “Kill a Gook for Jesus! Kill a Commie for Christ!”

Nice.

Anybody wish to guess the denomination that would have a minister playing so fast and loose with the Sixth Commandment, not to mention the Beatitudes? Yes, you in the back, Reverend Falwell — what’s your guess?

I listened to two high school teachers bemoaning their “lazy Mexican” students. “It’s like an entire culture of unaccountability,” one said. “And if I say a word about it, I’m a racist!” The other couldn’t agree more. “Joo can’t say dat to me, joo ees raceest,” she mocked, and they laughed. I also heard them both bemoaning the posture, attitude, and irresponsibility of their non-Mexican students, but in those cases, it’s because they’re teenagers. For the Mexican kids, the same behaviors are attributed to Mexicanness. One group of sinners, in other words, is unforgiven.

On the ride home from one of the reunions, Erin told of a cousin she idolizes saying “I hate Democrats!” then informing the rest of the group in a whisper that Obama is “a Muslim.”

My kids are plenty old enough to pick up on these things. Connor was nine when he asked, “Why does [Beloved Relation X] hate A-rabs so much?” with the requisite long ‘A’. In answering such questions, I find myself struggling more than anything with The Mix, trying hard to emphasize the positive qualities of religion, to keep them away from the broad brush, to remember that we are all a Mix, to not to create my own category of unforgiven sinners. Again — many of the religious folks in their lives are wonderful, kind, and ethical. But I can also say, with honest regret, that the greatest poison my kids hear comes from fervently religious people they know and love.

Why is that? (he asked rhetorically). And why am I so damned hesitant to point it out?

not just another day

A few months ago I caught sight of a forehead-thumpingly dumb initiative called “Just Another Day,” an attempt by some atheist activists (including the usually level-headed Ellen Johnson) to encourage nonbelievers to treat the presidential election of November 4 as “just another day” by refusing to vote. The candidates are climbing over each other to pander to the faithful, went the reasoning, and until they begin to represent my interests as well as those of the religious majority, I’m taking my cool Pee-Wee Herman action figure home where no one else can play with it.

Solid proof that the religious have no monopoly on delusion and self-satire.

The initiative now seems to have been scrubbed from the Internet — no small feat. I can find no trace. And that’s good, because although both major candidates are indeed playing up their supercalinaturalistic bona fides, one of them has distinguished himself with comments like this:

If you have not heard this unprecedented, jaw-droppingly, hair-blow-backingly brilliant speech, here’s a longer clip. (I’ll paste it at the end as well.)

And then we have business as usual. (Is it true that we blink more rapidly when we know we are not being truthful?):

So one candidate appears to have read and understood the Constitution and (better yet) to have internalized its implications and its spirit, while the other has apparently read Chuck Colson.

Regardless of Obama’s personal religious beliefs, I find his grasp of this issue incredibly encouraging. I don’t need a president who shares my every view. I would like one with a solid handle on the principles on which the nation is predicated. And if I’m not mistaken, I’ve found one. So I’ll be in the sandbox with the rest of you on November 4.

And yes, you can play with my Pee-Wee.

__________________________________

A five-minute clip of Mr. Obama’s speech. Do not pass go until you hear it.