believe you me

The Meming of Life is back in the saddle after the third and final family reunion of the summer. The blog’s new look should be online shortly. Nine days from now, we will hear an alarm clock for the first (damn) time in three months as school resumes. Today my boy comes of age, beginning a year-long project that (should he choose to accept it) will culminate in a celebration, special gifts, new rights, and new responsibilities as he enters high school.

Posts to come on all of the above — but for now, let’s ease into August with something I’ve wanted to feature for some time…

I suggest in the seminars that nonreligious parents do what they can to make beliefs a normal topic of discussion in their extended families. Not that it is in mine — my poor dear relatives seem positively constipated on the topic of religion since my book came out. I think they’re hoping to avoid offending me, not realizing that (1) I am pert near unoffendable, and (2) I would be delighted if our differences could be openly acknowledged and we could talk to / joke with /challenge each about something more interesting than truck transmissions and Dancing With the Stars.

One guaranteed conversation starter is the Belief-O-Matic Quiz at Beliefnet.com. Take the quiz, talk about your results, and invite other family members to do the same.

The quiz asks twenty multiple choice worldview questions, then spits out a list of belief systems and your percentage of overlap with each system. In other words, it doesn’t tell you what church you go to, but it might tell you what church you should be going to. If any.

Email all family members the link before your next gathering.

My most recent result:

1. Secular Humanism (100%)

2. Unitarian Universalism (92%)

3. Liberal Quakers (76%)

4. Theravada Buddhism (73%)

5. Nontheist (73%)

6. Neo-Pagan (65%)

7. Mainline to Liberal Christian Protestants (59%)

8. New Age (49%)

9. Taoism (47%)

10. Orthodox Quaker (43%)

11. Reform Judaism (41%)

12. Mahayana Buddhism (41%)

13. Sikhism (32%)

14. Jainism (30%)

15. Bahá’í Faith (30%)

16. Scientology (28%)

17. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) (27%)

18. New Thought (25%)

19. Seventh Day Adventist (22%)

20. Christian Science (Church of Christ, Scientist) (20%)

21. Hinduism (20%)

22. Mainline to Conservative Christian/Protestant (20%)

23. Eastern Orthodox (18%)

24. Islam (18%)

25. Orthodox Judaism (18%)

26. Roman Catholic (18%)

27. Jehovah’s Witness (13%)

Now tell me that’s not a fun and interesting conversation starter.

In addition to being awfully Buddhist, I’m apparently less Jewish now (18 percent) than I was three years ago (38 percent) but slightly more Catholic (18 vs. 16 percent). And this is the most interesting feature of the quiz — the revealed common ground.

Even so, comparing results between people can carry a very different message. Just for sport, I took the quiz answering as if I were a Baptist evangelical:

1. Eastern Orthodox (100%)

2. Roman Catholic (100%)

3. Mainline to Conservative Christian/Protestant (99%)

4. Jehovah’s Witness (87%)

5. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) (83%)

6. Seventh Day Adventist (80%)

7. Orthodox Judaism (79%)

8. Islam (70%)

9. Orthodox Quaker (67%)

10. Hinduism (59%)

11. Sikhism (51%)

12. Mainline to Liberal Christian Protestants (40%)

13. Bahá’í Faith (37%)

14. Jainism (37%)

15. Reform Judaism (30%)

16. Christian Science (Church of Christ, Scientist) (21%)

17. Mahayana Buddhism (21%)

18. Theravada Buddhism (21%)

19. Liberal Quakers (20%)

20. Scientology (19%)

21. Nontheist (18%)

22. Unitarian Universalism (16%)

23. New Thought (15%)

24. Neo-Pagan (8%)

25. New Age (4%)

26. Taoism (2%)

27. Secular Humanism (0%)

Have the heart pills ready when Born-Again Grandma finds out she’s 70 percent Islamic.

It might seem surprising at first that Catholic and Conservative Protestant come out so close, but the differences in the two, like the devil himself, are primarily in the details. The quiz goes after foundational worldview questions, not the piles and piles of minutiae that kept the two at each others’ throats for so many centuries.

But take a look at the gap between conservative Christianity and secular humanism. It’s true that the churched and unchurched share an incredible amount of common ground as human beings, but when it comes to the worldview questions around which the quiz is built, a chasm opens. In the great metaphysical Q&A, my conservative relations and I share between zero and 20 percent.

So while we’re celebrating the humanistic ties that bind us, it doesn’t hurt to recognize the challenge faced by bridge builders on both sides.

Perhaps the most revealing result of the two lists is where mainline-to-liberal Christianity falls on each. I share 59 percent with the average liberal Christian, while our hypothetical conservative Baptist shares 40 percent with the liberal Christian. Mainline-Liberal Christians have a good deal more in common with secular humanists than they do with Pat Robertson and Benedict XVI. Both humanists and liberal Christians would benefit enormously from recognizing, and building on, this large overlap.

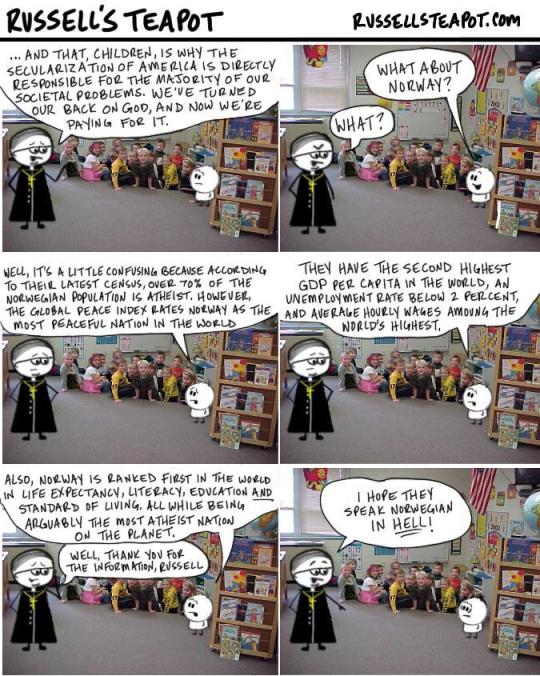

The humanistic hell that is Norway

As we pull together Connor’s coming of age process for the coming year, one country keeps popping its blonde head into the frame–Norway. No surprise: Norway is among the least theistic countries on Earth and has the longest continuous history of humanist coming-of-age ceremonies. I mentioned this in passing late last year:

One of the most marvelous and successful [humanist coming-of-age] programs in the world is the Humanist Confirmation program in Norway. According to the website of the Norwegian Humanist Association, 10,000 fifteen-year-old Norwegians each spring “go through a course where they discuss life stances and world religions, ethics and human sexuality, human rights and civic duties. At the end of the course the participants receive a diploma at a ceremony including music, poetry and speeches.” They are thereby confirmed not into atheism, but into the humanist values that underlie all aspects of civil society, including religion.

As for Norway itself, I could go on and on. It is among the nations with the lowest rates of crime and poverty while topping the developed world in generosity and nearly all standards of living. Yet fewer than 10 percent of Norwegians attend church regularly.

I’ll let Russell’s Teapot take it on home:

[CAVEAT LECTOR: The cartoonist has overreached a bit here. Sixty-eight percent of the Norwegian population self-identifies as nontheistic. A much smaller percentage (around 10 percent) self-identify as atheists. Hat tip to MoL reader Ellen!]

guessing games

There is a game that my girls (10 and 6) play at great length. One of them puts her hands over her eyes and asks, “Are my eyes open or closed?”

The guesser stares at the back of her sister’s hands. “Uhhhh…open!” at which point the first one pulls her hands away to reveal, most often, closed eyes.

I hate this game.

I hate it because even if everyone is rigorously honest (pfft), there is literally no way to know in the first place. The guess is necessarily, definitively wild. The only honest answer is “I have no idea, go away.”

Once in a while, forgetting my opinion on the matter, one of them will turn the latest version on me. “Daddy,” Laney will say, hands behind her back, “guess whether my fingers are crossed!”

“Go far away.”

“Just guess!”

Just guess. I only like educated guessing. I like looking at scraps of information and trying to tease out the answer to a puzzle. That’s fun. But in this case she’s essentially saying Take a random stab at it, based on nothing. Say the first thing that comes to mind. Go with your gut. Reach out with your feeeelings. Use the Force, Luke. I don’t wanna.

As Malcolm Gladwell illustrates in the fascinating (though subtitularly offputting) Blink — The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, what we call “going with your gut” can actually be effective when there are data. We often make decisions in a blink that turn out to be informed by evidence that we perceived but didn’t consciously process. Gladwell goes to great lengths to note that what we call “intuition” is not magic — it’s regular old cognition, just quick and subconscious.

I usually end up playing along with the girls, just to be Mr. Daddy Fun Fun, but I quit after two or three rounds because the whole idea of pretending I have a clue when I have none irritates me. It just does.

Becca went through a period of playing the same game when pregnant with each of our kids. In the dark of our room, three minutes after the light went out, her voice would suddenly pipe up: “Do you think it’s a boy or a girl?”

“Well of course.”

“Which one?”

“Oh, which one? No idea.”

“Just guess, silly!”

“…”

I guess I didn’t care enough about being Mr. Husband Fun Fun to play along. She got her revenge, though. The girls learned the game in utero.

is nothing sacred? epilogue

I recently offered my thoughts on the difference between pointless and pointful challenges to sacredness:

Why does the David Mills video I’ve denounced strike me instantly as a profoundly stupid gesture, while [Webster Cook’s removal of a communion wafer from a mass] strikes me just as instantly as an interesting and thought-provoking transgression?

The reason, I think, is that the act of crossing the church threshold with that wafer (whether he intended this or not) is a kind of Gandhian gesture. Doing something so seemingly innocuous and eliciting an explosive, violent, even homicidal response is precisely the way Gandhi drew attention to cruel policies and actions of the British Raj, the way black patrons in the deep South asserted their right to sit on a bar stool, while whites (enforcing a kind of sacred tradition) went ballistic….

Mills’ feces-and-obscenity-strewn video, on the other hand, had offense not as a byproduct but as its intentional essence. Of Cook, one can say, “he just walked out the door with a wafer,” and the contrast with the fireworks that followed is clear. But saying, with sing-song innocence, that Mills was “just smearing dogshit on a book while swearing, gah,” doesn’t achieve quite the same clarity. Even though it shares the act of questioning the sacred, it’s much less interesting and much less defensible.

When PZ Myers of the science blog Pharyngula made known his intention to desecrate a communion wafer, I held my breath a tad, wondering which way it would go. Would he do something stupid or something thought-provoking? Pointless or pointful?

Now Myers has made his gesture — and I couldn’t be more thrilled:

This fascinates me even more than Wafergate because it is so achingly close to the Mills’ video on the surface, yet light years away in substance.

Had Myers theatrically smashed a pile of communion wafers with a hammer while laughing hysterically, he’d have undercut his own point that it is just a “frackin’ cracker.” Instead, he made use of that old and brilliant insight that the opposite of love is not hate but indifference.

So he quite simply threw it out, along with the coffee grounds.

Granted, he put a nail through it, a subtle and ironic comic touch that I’m doomed to love. But the real brilliance is in the background. Myers has also thrown out pages of the Koran and The God Delusion. He isn’t allowing anything to be held sacred. ALL ideas must be exposed to disrespect, disconfirmation, and disinterest. The good ones can take the abuse, and the bad ones, to quote Twain, will be “[blown] to rags and atoms at a blast.” If instead we shield a set of beliefs or ideas from scrutiny or attack, the bad bits survive along with the good.

Myers is also making the important point that these are NOT ideas in the garbage — they are paper and wheat, which must not be confused with the things they represent any more than a flag should be revered in lieu of the principles for which it stands.

Toss in a wink at Ray Comfort’s banana argument against atheism and the whole tableau simply rocks with meaning, power, humor and intelligence. And pointfulness.

Myers’ post is long, but please take a few minutes to read it. I can’t recommend it highly enough for its provision of context and just plain smarts. The final paragraph drives it all home:

Nothing must be held sacred. Question everything. God is not great, Jesus is not your lord, you are not disciples of any charismatic prophet. You are all human beings who must make your way through your life by thinking and learning, and you have the job of advancing humanities’ knowledge by winnowing out the errors of past generations and finding deeper understanding of reality. You will not find wisdom in rituals and sacraments and dogma, which build only self-satisfied ignorance, but you can find truth by looking at your world with fresh eyes and a questioning mind.

When it comes to challenging sacredness, if I can get my kids to grasp the difference between Mills and Myers, I’ll count myself proud.

no cats were harmed

- July 24, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In myths, Science

23

23

Mother: “Don’t ask so many questions, child. Curiosity killed the cat.”

Willie: “What did the cat want to know, Mom?”

—The Portsmouth Daily Times, March 1915

An interesting character pops up in religion and folklore around the world and throughout history: the curious and disobedient woman. Here’s the story: A god/wizard gives a woman total freedom, with one exception—one thing she must not do/eat/see. She battles briefly with her curiosity and loses, opening/eating the door/jar/box/apple and thereby spoiling everything for everybody.

Curiosity didn’t just kill the cat, you see. It unleashed disease, misery, war and death on the world and got us evicted from a Paradise of blank incuriosity and unthinking obedience.

Bummer.

That this cautionary tale is found in religions worldwide leads me once again to conclude that religion isn’t the source of human hatreds, fears, and prejudices—it’s the expression of those fundamental human hatreds, fears, and prejudices, the place we put them for safekeeping against the sniffing nose of inquiry. And since the story includes three things powerfully reviled by most religious traditions (curiosity, disobedience, and women), it’s not surprising to find them conveniently bundled into a single high-speed cable running straight to our cultural hearts.

I could do pages on Eve alone and her act of disobedient curiosity with the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil (Was she really punished for wanting to know the difference between right and wrong, or just for disobedience? How could she know it was wrong to disobey if she didn’t yet have knowledge of good and evil? etc). Then there’s Lot’s wife, poor nameless thing, a woman (check!) who was curious (check!) and therefore disobeyed (check!) instructions to not look back at her brimstoned friends and loved ones. Islam even coined a word for a disobedient woman – nashiz – and decreed a passel of human punishments for her in sharia law.

But neither Eve nor Mrs. Lot was the first nashiz woman to cross my path. Lovely, nosy Pandora was my first.

Pandora was designed for revenge on humanity by the gods, who were angry at the theft of fire by Prometheus. According to Hesiod, each of the Olympians gave her a gift (Pandora = “all-gifted”). She was created by Hephaestus in the very image of Aphrodite (rrrrrrowww). Hermes gave her “a shameful mind and deceitful nature” and filled her mouth with “lies and crafty words.” Poseidon gave her a pearl necklace, which (unlike the deceitful nature, for example) was at least on her registry. But the real drivers of the story were the last two gifts: Hermes gave her an exquisitely beautiful jar (or box) with instructions not to open it, while Hera, queen of the gods, blessed her with insatiable curiosity.

Nice.

Long story short, once on Earth, Pandora’s god-given curiosity consumed her and she opened the jar/box, releasing war, disease, famine, and talk radio into the world. Realizing what she had done, she clamped the lid on at last, with Hope alone left inside.

(This is usually interpreted as Hope being preserved for humankind as a comfort in the face of the terrors, but even at the age of ten I realized that by trapping Hope in the jar, she kept it out of the world. Are there no mythic traditions with continuity editors?)

This week I came across the anti-curiosity tale in yet another form, one I’d never seen before–a Grimms’ fairy tale called Fitcher’s Bird:

Once upon a time there was a sorcerer who disguised himself as a poor man, went begging from house to house, and captured beautiful girls. No one knew where he took them, for none of them ever returned.

One day he came to the door of a man who had three beautiful daughters. He asked for a bit to eat, and when the oldest daughter came out to give him a piece of bread, he simply touched her, and she was forced to jump into his pack basket. Then he hurried away with powerful strides and carried her to his house, which stood in the middle of a dark forest.

He gave her everything that she wanted. So it went for a few days, and then he said to her, “I have to go away and leave you alone for a short time. Here are the house keys. You may go everywhere and look at everything except for the one room that this little key here unlocks. I forbid you to go there on the penalty of death.”

He also gave her an egg, saying, “Take good care of this egg. If you should lose it, great misfortune would follow.”

She took the keys and the egg, and promised to take good care of everything.

As soon as he had gone she walked about in the house, examining everything. The rooms glistened with silver and gold. She had never seen such splendor.

Finally she came to the forbidden door. She wanted to pass it by, but curiosity gave her no rest. She put the key into the lock and the door sprang open.

What did she see when she stepped inside? A large bloody basin stood in the middle, inside which there lay the cut up parts of dead girls. Nearby there was a wooden block with a glistening ax lying on it.

She was so terrified that the egg slipped from her hand into the basin. She got it out again and wiped off the blood, but it was to no avail, for it always came back. She wiped and scrubbed, but she could not get rid of the stain.

Not long afterward the man returned from his journey and asked for the key and the egg. She handed them to him, and he saw from the red stain that she had been in the blood chamber.

“You went into that chamber against my will,” he said, “and now against your will you shall go into it once again. Your life is finished.”

He threw her down, dragged her by her hair into the chamber, cut off her head, then cut her up into pieces, and her blood flowed out onto the floor. Then he threw her into the basin with the others.

It gets worse, believe it or not, this charming children’s tale. Now I have to go away and leave you for a short time. You may read anything you wish on the Internet, but you may NOT, on pain of death, click on this link to read the rest of the story.

Given this glimpse into our cultural terror of curiosity, is it any wonder that religion and science are so often at loggerheads? One is fueled by the very thing the other has traditionally feared—the opening of interesting and forbidden jars.

_______________

NOTES

- Fitcher’s Bird is very closely related to (and probably the source of) the tale of Bluebeard.

- The phrase “Curiosity killed the cat” is in fact a much later corruption of the original “Care (i.e., worry) will kill a cat,” which appears in a Ben Jonson play of 1598.

souls of gold

- July 23, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids

15

15

[Get ready for a short flurry of posts. I’ll be off the net for five days next week, so I’m posting daily for the next five days to get some ideas off my sketchpad. Read at your leisure (or not). Sometime in early August I’ll launch the New Look.]

Having rhapsed waxsodic about my boy and my wife recently, I wanted to give my girls a big shout-out before moving on.

This may border on the sappy from the outside — my meter is indeed twitching — but I was moved by a recent loving gesture from Erin (10) and Delaney (6). This may be in part because of the occasional emails I get, weeping over the fate of my children, whose religionless lives are assumed to be cold and unemotional. A recent message mourned my kids’ lost opportunity to “develop they’re [sic] souls.” Like “sacred,” the word “soul” has at least two common meanings: (1) an immortal essence, or (2) a rich, emotional inner life. Removing religion may remove the idea of immortality, but (as you in the choir no doubt know) it has no effect on the richness of a person’s emotional life, on his or her ability to feel, empathize, love, and discover meaning.

My girls recently demonstrated the depth of their lovely second-definition souls as Becca and I celebrated our 17th anniversary last Sunday, two days after the family went to Six Flags.

“Stay out of the family room, stay out of the family room!” shrieked Delaney excitedly, waving her hands to block us on the stairs. We dutifully detoured into the dining room and sat, waiting for further instructions.

Five minutes later, we got the nod. “Mr and Mrs. McGowan,” Erin said, “come right this way.”

In the middle of the family room sat two chairs, one in front of the other, each with two strings depending from the back and another across the seat. Next to the chairs, stuck on a broom handle, was this sign:

We understood immediately.

During our day at Six Flags, Becca and I kept trying to ride a rollercoaster called the Great American Scream Machine. First I chickened out. When I finally decided I’d do it, the line was way too long. Finally we decided we’d go at the end of the day as our very last ride.

But as we headed that way, Becca and I realized that the girls (who had no interest in the Scream Machine) wouldn’t get another ride in if we did that. So we scotched our plans for a mutual G.A.S.M. and went instead to Splashwater Falls.

On the drive home, Erin looked out the window, pensively.

“What are you thinking about, B?” I asked.

“I feel bad that you guys didn’t get to go on the Scream Machine.”

“Yeah,” Laney added.

We waved it off, thanked them for thinking about us, assured them that the Falls was even more fun. But when we saw the sign, we knew they hadn’t bought it and had turned that karmic wheel to set things right.

They tied us is with the strings. “Okay everybody, here goes!!” they yelled, then shook our chairs and leaned them back (somehow) for the big uphill. “Clack clack clack clack clack!”

“Hold on, here’s the first hill, woohooooooooo!” They slammed our chairs forward to the floor. Erin reached over and switched on a table fan to blow in our faces. We threw our hands in the air and screamed. They shook the hell out of our chairs and screamed along with us.

At last it was over. They untied us and wished us a happy anniversary. Honestly, surrounded by golden souls like that, how could we not have one?

introducing connor mcgowan

- July 21, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids

27

27

Connor McGowan is a young man on the cusp of thirteen, living in Atlanta with his two sisters and his parents, one of whom am I. As my regular readers will know, I am immensely proud and honored to be his dad. He is intelligent, creative, funny, and deeply kind.

When he turns thirteen ten days from now, Connor will begin a year-long coming-of-age program of our own design. I’ll write about it as we go.

Even more exciting is the fact that Connor has now launched his own blog called THE WIDE SCREEN. He would be delighted if y’all would surf over there, take a look at his first posts and jot a comment or two.

BUT FIRST, by way of introduction, I thought I’d share some of his writing. Below is a short speech Connor wrote for a seventh grade assignment, one that shows his fascination with “personal improbability,” a.k.a. how amazingly unlikely was his birth.

Why Me? Why Not?

by Connor McGowan

Everyone, at some time in their childhood, has an image of themselves in the future. I want to be an astronaut. I want to be a construction worker. I want to be… These are the words of millions of children around the world. As the comedian George Burns put it, “I look to the future ’cause that’s where I’m going to spend the rest of my life.” But before we look to the future, we must look to the past. It’s the events of the past that decide who we are going to be, what our characteristics are, and even whether we are going to exist at all.

On April 23, 1862, a 19-year-old Confederate soldier was shot through the neck by a Yankee bullet. He lay on the battlefield, bleeding profusely, then was found and taken to a Yankee field hospital as a prisoner of war. The doctors were able to stop the bleeding just in time to save his life. If the bullet had entered his neck one inch further to the left, he would have died. I’m glad he didn’t, because if he had, I wouldn’t be giving this speech. That nineteen-year-old boy just happened to be my great-great-great grandfather.

Every one of us has a past full of moments where our ancestors came an inch away from death. But death is not the only thing that could have erased me, or any one of us. Even small, everyday decisions and events can have a huge impact on the future. Few people think about the amazingly small chance of them ever existing. Countless things had to go perfectly right all along the line. What if my dad married his first girlfriend instead of my mom? I wouldn’t have been born. What if my grandparents never met? I wouldn’t have been born. What if the marriage proposal my great-grandpa sent to my great-grandma got lost in the mail, and she married the mailman instead? You know the answer. And this goes on and on for thousands of generations and millions of people, all of them doing just what they had to do for me to be.

Now here I am, making decisions of my own, all of which will affect generations and generations of my descendants. When my family moved from Minneapolis to Atlanta, it almost certainly changed the person I will eventually marry, which means countless people who would have been born will not be, and others who would not have been born, will be. Even the smaller decisions will have a big impact — where I go to college, what job I’ll have, and whether I’m careful crossing the street. Some will change who I am. Some will change what I do.

So why me? Because of all those millions of millions of people making millions and millions of choices and taking chances, I am here, giving this speech. I am standing at the neck of an hourglass. Above me are my millions and millions of ancestors all leading to me. Below me are my descendants. My ancestors are frozen in place. But, as I make choices and take chances, my descendants are constantly changing.

Now even though we are the result of infinite decisions, and we have been able to take part in existence, it doesn’t last forever. But that doesn’t make me unlucky. As Richard Dawkins said, “We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place outnumber the sand grains of Arabia. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here.”

So why me? Why not?

______________________

(The hourglass thing just kills me. Entirely his own metaphor.)

So pop over to THE WIDE SCREEN and say hey to my boy!

i’ll give you something to scream about

- July 19, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In Atlanta, fear, My kids

16

16

I like to watch other people in horror.

–Delaney McGowan, age six, smiling while watching screaming riders on the GOLIATH rollercoaster at Six Flags Over Georgia

Now I know for a fact that she doesn’t enjoy genuine suffering in others, but Linky and I both like to watch other lunatics in the grip of relatively benign and self-selected terrors – ten story drops on a coaster or a bungee, for example, things neither she nor I would do ourselves, thangyavurrymush.

But my daughter hasn’t yet noticed the thing that really puzzles me: they aren’t actually “in horror.” They are, most of them, thoroughly enjoying themselves.

I don’t get it.

I don’t get it for two reasons. The first is that I don’t understand how one of our greatest naturally-selected fears – the fear of falling, of which rollercoasting is a (barely) controlled simulacrum – got itself converted to one of our greatest thrills.

Sure, I can rationalize it – something about confronting death and emerging victorious, I guess. But that’s neocortical stuff. When I find myself (usually as a result of succumbing to the shamelessly repeated lie, “Come on, it’ll be fun!!” from my spawn) plunging down a near-vertical drop of ten stories at freeway speeds, my neocortex is huddled in a corner of my skull, wetting itself. The limbic system naturally grabs the wheel, screaming something about the fast-approaching jungle floor.

It’s not that I’m not a thrillseeker. I yearn to be thrilled. We all do. The question is what thrills you. I happen to be thrilled by perfect comedic timing, a blow-your-hair-back argument on any side of any issue, long sightlines over water or wilderness, mutually great sex, devastating musical harmony, unforeseen movie plot twists, Connor’s inventiveness and Delaney’s machine-gun laugh. I can sometimes even get my mind clear enough to be thrilled to be alive.

Which is exactly why simulated death-defiance makes me really, really unhappy.

I don’t call it a phobia, since “phobia” is defined as an irrational fear. A paralyzing fear of Regis Philbin or of macaroni might be irrational. Fear of death, or of things that could lead to it, is not.1

Cut to a speedboat coursing over the Lake of the Ozarks last week. (It’s a family reunion that includes a half dozen sporty cousins of mine who water-ski, Seadoo, skydive, speedboat, parasail, and just generally court risk as avidly as I avoid it. I’m in my forty-fifth year of hearing “Aw, come on!” from them and feeling like a poodle in a dogsled team.) From the back of the boat runs a rope, taut and twanging like a string on a washtub bass. At the end of the rope is an inflated tube, across which is sprawled my thirteen-year-old son and his younger cousin.

The boat makes a quick turn and the tube is sent skittering sidelong over the wake. Though it’s been years, I have done this, so I know that moment. If the turn is fast enough and the water rough enough, the tube will gradually tip, then vibrate, and finally tumble wildly like a flipped coin, throwing the rider or riders into the water at 40 mph. If you’re lucky, you end up in the path of a drunk hillbilly on a Seadoo, and death comes quickly.

Okay, I’m projecting.

But here’s the thing. I looked back at the face of my boy, right in the moment of maximum instability, the very moment when my own face would be a mask of concentrated unhappiness, and he was smiling. No no, not just smiling: his face looked to be in danger of splitting wide open. At the exact moment I would be least happy, his joy was positively orgasmic.

Why?

I’ve always figured my dad’s death when I was thirteen had something to do with my risk-aversion. I certainly lost all illusions of my immortality that day. But I’ve since learned that PET scan research is turning up two very different neurological responses to danger. It seems that you are either wired to love or hate the experience of risk. So maybe I’ve always been wired to hate it. The question remains: why did natural selection endow anyone, much less a sizable whack of humanity, with such a rabid taste for it?

Yesterday was another risk-immersion experience for me: a family trip to Six Flags. We divided into two groups by wiring: Connor, a friend, and Connor’s awesome (and risk-okiedokie) Aunt Beth went one way…

…while Becca, her mom, the girls and I went another.

In our final minutes at the park, Erin and Delaney suddenly decided it was time for a bit of terror and pointed to Splashwater Falls. It’s the simplest of all log flumes. No futzing around with zigzag courses through faux mountains and animatronic mining camps. They simply take you to the top of a 50-foot water drop and send you hastily down.

“You sure about this one?” I asked Delaney, who has a history of screaming for release from rollercoasters in the seconds before departure.

“Yep!”

“Okay! I’m psyched!” I actually was. For some reason I love water rides, no matter how insane.

It was on the incredibly long uphill, during that unmistakable ratcheting for which you know you’ll shortly pay, that she started to lose it. Nooooooooooo, she moaned, then began sobbing hard. Noooohohohohohohoho…

I put my arm around her. “You know we’re safe, right?” I said. No answer. She was now no-kidding terrified. “You won’t even believe how quick it goes,” I offered, knowing that I could only have sounded like the ax-wielding executioner whispering to Anne Boleyn.

We left the top, dropped like a rock, and I felt – there was no mistaking it – a genuine thrill. We hit the bottom, sending a magnificent wall of water over the crowd on the bridge. I was laughing like an idiot.

Then I remembered. I turned to Delaney, who was soaked to the skin. She slowly turned to look at me, her eyes intense.

“Again,” she said. “Again.”

__________________________

1Even though the “irrational fear of death” has its own name, thanatophobia, it shouldn’t.

is nothing sacred?

‘Body Of Christ’ Snatched From Church, Held Hostage By UCF Student

I smiled. I just love The Onion. Then I realized this was an actual news headline about an actual event. On Earth.

I hadn’t planned on writing about this. I’m trying to maintain a semblance of focus in this blog. But then the student’s father began defending his son in comment threads on Catholic blogs, and I had my parenting angle. Which I’ll get to. First, though, for the three of you who don’t know what I’m on about — the story that ran below that headline:

Church officials say UCF Student Senator Webster Cook was disruptive and disrespectful when he attended Mass held on campus Sunday June 29. It was during that Mass where Cook admits he obtained the Eucharist.

The Eucharist is a small bread wafer blessed by a priest. According to Catholics, the wafer becomes the Body of Christ once blessed and is to be consumed immediately after a minister passes it out to churchgoers.

Cook claims he planned to consume it, but first wanted to show it to a fellow student senator he brought to Mass who was curious about the Catholic faith.

“When I received the Eucharist, my intention was to bring it back to my seat to show him,” Cook said. “I took about three steps from the woman distributing the Eucharist and someone grabbed the inside of my elbow and blocked the path in front of me. At that point I put it in my mouth so they’d leave me alone and I went back to my seat and I removed it from my mouth.”

A church leader was watching, confronted Cook and tried to recover the sacred bread. Cook said she crossed the line and that’s why he brought it home with him.

“She came up behind me, grabbed my wrist with her right hand, with her left hand grabbed my fingers and was trying to pry them open to get the Eucharist out of my hand,” Cook said, adding she wouldn’t immediately take her hands off him despite several requests.

Cook is upset more than $40,000 in student fees have been allocated to support religious organizations on campus for the 2008-2009 school year, according to student government records. He denied he is holding the Eucharist hostage to protest that support.

Regardless of the reason, the Diocese says its main concern is to get the Eucharist back so it can be taken care of properly and with respect. Cook has been keeping the Eucharist stored in a plastic bag since last Sunday.

“It is hurtful,” said Father Migeul [sic] Gonzalez with the Diocese. “Imagine if they kidnapped somebody and you make a plea for that individual to please return that loved one to the family.”

The Diocese is dispatching a nun to UCF’s campus to oversee the next mass, protect the Eucharist and in hopes Cook will return it.

You will no doubt be shocked to learn that the student has received several death threats. As a result of that exalted terrorism, he has now returned the Divine Saltine.

Despite the fact that almost everyone in the story is acting like a baboon, this is not just a toss-off piece of silliness to me. It taps fascinating issues around the intersection of sacredness, tradition, tolerance, the media, force, academia, healthy snacking, and free expression. Most such stories are merely about baboons, but this one I simply can’t get out of my head.

Question #1: Why does the David Mills video I’ve denounced strike me instantly as a profoundly stupid gesture, while this strikes me just as instantly as an interesting and thought-provoking transgression?

The reason, I think, is that the act of crossing the church threshold with that wafer (whether he intended this or not) is a kind of Gandhian gesture. Doing something so seemingly innocuous and eliciting an explosive, violent, even homicidal response is precisely the way Gandhi drew attention to cruel policies and actions of the British Raj, the way black patrons in the deep South asserted their right to sit on a bar stool, while whites (enforcing a kind of sacred tradition) went ballistic.

No, the analogy is not perfect. Cook was not defending a right. But he did similarly draw attention to an element of belief (crackers are different once a priest’s hand has waved over them) that can tip quite suddenly into dangerous lunacy at the slightest provocation. Isn’t that a point worth making?

Mills’ feces-and-obscenity-strewn video, on the other hand, had offense not as a byproduct but as its intentional essence. Of Cook, one can say, “he just walked out the door with a wafer,” and the contrast with the fireworks that followed is clear. But saying, with sing-song innocence, that Mills was “just smearing dogshit on a book while swearing, gah,” doesn’t achieve quite the same clarity. Even though it shares the act of questioning the sacred, it’s much less interesting and much less defensible.

Question #2: Is nothing sacred?

Becca and I debated this at length. She said that all declarations of sacredness should be respected and left alone. I countered by saying the very idea of sacredness is worth discussing, and that the best way to draw attention to something of this kind — like an unjust law — is by violating it and allowing the results to play out. Should we “respect and leave alone” the opposing, irreconcilable claims of sacredness that keep the Middle East aflame? The sacred idea that men should have dominion over women? The list goes on.

But the question remains: Should anything be held “sacred”? I think the answer is yes and no, because the word “sacred” has two different major meanings.

Sacred is used to denote specialness, to mark something as awe-inspiring, worthy of veneration or deserving of respect. In this first sense, the nonreligious tend to hold many things sacred — life, integrity, knowledge, love, a sense of purpose, freedom of conscience, and much more. One might even hold sacred our right and duty to reject the second meaning of sacred: something inviolable, unquestionable, immune from challenge.

This second definition of sacredness is much like the concept of hell — it exists primarily as a thoughtstopper. As such, it has no place in a home energized by freethought. One of the most sacred (def. 1) principles of freethought is that no question is unaskable, no authority unquestionable.

Which bring me to Question #3, the parenting angle. If this were my son, and he had undertaken this as a kind of civil disobedience, would I be proud?

Immensely. Intensely. Uncontainably. It’s Kohlberg’s sixth stage of moral development, and it makes me weak in the knees.

Encouraging reckless inquiry in your kids means laughing the second definition of “sacred” straight out the door. Given that understanding of the dual meaning of sacredness, it should now make sense that I consider it a sacred duty to hold nothing sacred.

my (much) better half

- July 15, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, Parenting

14

14

Back now from Family Reunion A, a good time at the Lake of the Ozarks. The B-Side Family Reunion (Becca’s side) is in ten days in the mountains of North Carolina. Between the two is a mountain of catching up. My word, I hadn’t even heard about Crackergate (my new all-time favorite entry in the category of unintentional self-parody) until just now.

I’ll start the week with a brief hymn to my wife Becca, who has once again accidentally reminded me that whenever a pollster asks how many adults live in our home, the correct answer is “one.”

It was late. We had stayed at the lake until after lunch on Sunday to give the kids one last chance to put an eye out with a SeaDoo. Now we’d driven 400 miles with 40 to go before not even home, but a one-star motel in Clarksville, Tennessee. And we were in the twentieth minute of a game of Initials on which Connor (shortly 13) had insisted.

The rules are simple. One person offers the initials of another person, famous or non. The others ask yes-or-no questions until they figure out who it is. Unlike Twenty Questions, this one has no mercifully pre-programmed end. You go until you stop. I like this game between 9am and 9pm. It was 10:15.

“RR!” the boy repeated for the nth time, exasperated. “Come on, you guys, jeez!”

We’d established in the opening minute that RR was a famous fictional male, dropping Ronald Reagan, Roy Rogers, and Ralph Reed off the table. Just ten minutes later, we had established that RR was a superhero.

“I can’t believe you guys! RR,” he whined, leaning on the second letter as if it helped. I desperately wanted silence, which only seemed likely if we guessed the damned identity of R frickin’ R.

“Do both Rs stand for regular names?” I asked.

“No, it isn’t!”

Aha. “Is the first one a title? Like ‘Reverend’?”

“That’s right, Dad. It’s the famous superhero, Reverend Rick.”

Smartass. “Is the first R an adjective?”

“Adjective…I always get those confused.”

“Descriptive word. Like red or round.”

“Yes! It’s an adjective!”

Aha. “Is the first R red?”

“YES! Jeez, it’s about time. Now you’ll get it.”

Then ten more minutes passed, his frustration rising every time I offered Red Rover? or Red Roof-inn?

“Are you sure this guy is a superhero?” Becca asked.

“Holy buckets, you guys, I can’t believe it! Yes, he’s a superhero, now COME ON! Red R!!!”

At last we did the unthinkable and surrendered, hoping he’d accept.

“You’re gonna be so mad at yourselves,” he promised.

“I’ll flip the car to punish myself.”

“Okay, here it goes. Are you ready?”

“Yes.”

“Red Robin.”

Becca and I looked at each other.

“How could you not get that?!” he whined. “Red Robin, jeez!”

“I’m sorry, Con,” I said, holding my fire for the moment. “Who is Red Robin?”

“WHO IS RED ROBIN?!” He couldn’t believe it. “You’ve never heard of Batman and Red Robin??”

“…”

Twenty minutes of guessing, twenty minutes that could have been silent save the rhythmic thrum of the tires — twenty irretrievable minutes passed before my eyes. Gone forever. “Connor,” I said, “it isn’t…”

Becca’s hand came to rest lightly on my arm, and I stopped in mid-sentence.

“Red Robin,” she said. “I can’t believe we missed that.” She squeezed my arm affectionately.

“Jeez,” I said. “Red Robin. Of course.”

He settled back in his seat, victorious. Becca patted my arm, and a sign promised Clarksville in 23 miles.

____________________

[For any DC Comics fans out there: I have since learned that, yes, there is apparently an obscure Red Robin in a 1996 comic book series called Kingdom Come. But Connor knows Robin only through the Batman films.]