When Truman Touches the Wall

15 min

The climactic scene in The Truman Show is so intensely satisfying that it still stuns me after all these years. One musical technique plays a big part in that.

Non-harmonic tones are notes that are not part of the chord of the moment but still make sense because they follow certain patterns. The non-harmonic tone that makes the climax of The Truman Show so devastatingly perfect is a pedal point (or simply ‘pedal’).

The rule for a pedal is simple: A note starts out as part of a chord, then it doggedly hangs on, even as the chords change around it. You’re still hearing that same note, maybe held out long, maybe pulsing in quarters or eighths. Sometimes it’ll belong to the chord and sometimes not, but regardless, it keeps sounding. That’s a pedal.

Tom Petty uses a double pedal all the way through Free Fallin’. Two notes are unchanging in the guitar, C and F, ringing straight through the song even as the chords change around them (39 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lWJXDG2i0A” parameters=”start=3 end=42″ /]

Sometimes it’s just a nice effect. But a pedal point can also serve the emotional purpose of establishing reality, for better or worse — a steady insistence that we accept the situation.

One of the most stunning uses of a pedal point was in the recessional at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, a piece called “Song for Athene” by John Tavener. Listen to the low F in the basses (same note as Free Fallin’). It starts right at the beginning. Better still, hum along with that long note in any octave so you can feel the music moving around that unchanging core, moving between minor and major, dissonance and consonance, darkness and light. Go all the way to 5:44 if you can — it’s one of the most profound musical settings you’ll ever hear, especially if you hum that pedal all the way:

There was a feeling of unreality when the news of Diana’s death first broke. It seemed somehow impossible. Tavener’s pedal had the effect of cementing our acceptance: Oh my God, she really is dead.

Now listen to the end of The Truman Show. The pedal begins at 1:00, those steady quarter notes down in the low strings, but don’t skip that first minute to set it up:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gn5kuDdeGzs” /]

We spent the film watching Truman struggle with uncertainty and confusion, wanting answers. When his hand touches the wall, he finally has his answer — and the pedal, the music of finality, tells us it’s true.

Follow Dale on Facebook…

I’m Not Saying Aliens Wrote This House of Cards Cue…

House of Cards is brilliantly scored, soup to nuts. Last month I wrote about the opening title theme. But one cue is even more special — the evocative underscoring that often makes an appearance when Frank and Claire share a cigarette and conspire. It’s called “I Know What I Have To Do”:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/fo781LEHbqc” /]

Apparently it’s special to other people as well: several videos on YouTube will teach you how to play it — an unusual tribute for a background cue. As a bonus, most of them will teach you how to play it wrong (16 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fmchtLg743I” parameters=”end=16″ /]

Nope. Try again (10 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpbAirHi3K0″ parameters=”start=70 end=80″ /]

Sorry, no.

I’m not pointing out these errors to be a pedantic little theorywanker. That’s just a bonus. The understandable errors they’re making reveal something cool and interesting about the piece itself: the fact that it was written by aliens.

You know when kids are first learning to speak, and they say things like, “I goed to the farm and seed the sheeps”? It’s called overregularizing, and it’s actually a sign of sophistication in the learner. Instead of making the daft and pointless transformations from go to went, see to saw, and sheep to sheep, kids regularize all the verbs and plurals to the perfectly good rules they’ve learned, and Bob’s your uncle.

The same thing is going on musically in the errors that pop up when Earthlings try to figure out this House of Cards cue.

In the harmony post, I mentioned that most Western music is based on piles of thirds. Our harmonic language is triads with notes a third apart:

Our ears are used to that map. Give us harmonies based on thirds and our compass points home. The wrong tutorials are “fixing” what they hear to give the illusion of knowing which way is north.

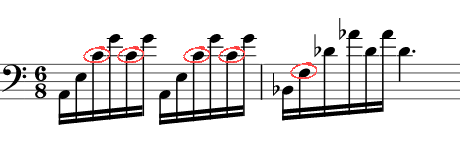

Here’s what the tutorials above are doing (wrong notes circled):

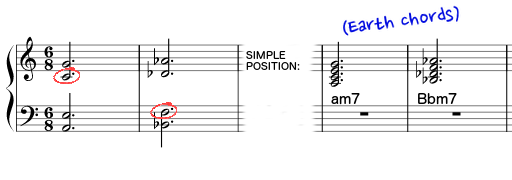

Simplified into chords:

But this House of Cards cue isn’t based on thirds (tertian). It’s quartal and quintal — built with fourths and fifths.

Fourths and fifths are great and common in melodies. The first two notes of Amazing Grace are a fourth, as are the first two of Taps. The first leap in Star Wars is a fifth. They also appear all the time in harmony. But when they do, they are mostly flippable into simple position triads — a pile of thirds, as seen in the perfectly Earthly chords above.

But not this time. This music is unflippably strange:

The notes are now right, which is to say they’re correctly wrong. Musicians, look at that bloody mess. What key has Gb, G, Ab, A, D, Db, and E natural? Then there’s that fourthi-fifthiness. Here it is, simplified:

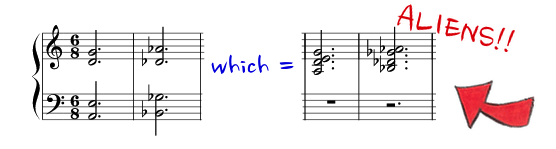

Look at that! Notes all sticking out to the sides, making Baby Jesus cry. It’s just wrong, even without the right hand melody, which makes it even stranger when added in. But that wrongness is why it’s worth talking about. Compare them side by side now, Earthling first, then alien:

It’s subtle, but believe me, the hairs on your neck know the difference.

Like little kids “fixing” grammar, the tutorials are accidentally adjusting the strangeness into something that makes sense. By budging two notes, they turn fourths into thirds, went into goed, alien music into something we can understand. In so doing, they erase a lot of the eerie quality — that unmoored, homeless fourthiness.

Now sure, you can have fourths and seconds and sevenths and all sorts of other things in normal Western Earth music. But there are rules for how they move to harmonically stable intervals, dammit, and these just aren’t following those rules. They’re sliding from one unstable, unholy mess into another.

By the way, I’ll tell you what compositional technique he used to arrive at this. It’s one I used all the time when I was trying to get outside of the box. It’s called Flopping Your Hands on the Keys to See if the Seed of Something Cool Comes Out. I say this with 99% confidence.

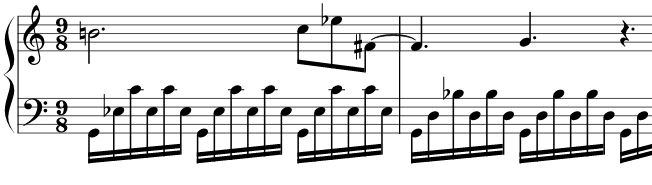

Not true for the next few bars, which suddenly go all rulesy — but it’s the complex harmonic rules of the Romantic period:

Here’s what that sounds like (12 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/fo781LEHbqc” parameters=”start=62 end=74″ /]

Oh my gourd, that is gorgeous. It could have been lifted straight from a Chopin nocturne.

Finally, here’s “I Know What I Have to Do” in scene. Turn it way up:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/0Rqm6dFvDAA” /]

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!