Ep 8: The Moment I Surrendered to John Williams

I had never felt so tangibly dropped into another world.

Listen to “Ep 8: The Moment I Surrendered to John Williams” on Spreaker.

Ep 3: When Truman Touches the Wall

From a Bach fugue to Diana’s funeral to Truman’s wall, this technique is the music of finality.

Listen to “Ep 3: When Truman Touches the Wall” on Spreaker.

Hiding in Plain Sight: The Greatest Musical Easter Egg Ever

5 min

I just tripped over a music theory Easter egg that’s been hiding in plain sight for 50 years. It’s easy to understand with a little explanation, and it just had to be intentional.

Last week I wrote about Mozart’s use of non-harmonic tones — pitches that don’t belong to the chord of the moment:

They usually fit one of 12 rules (patterns with the notes around them), which is how your ear makes sense of the pitch despite it being a chordal immigrant.

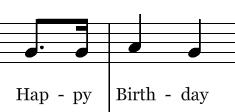

One of the simplest non-harmonic patterns is the neighbor tone. Start on a note that’s in the chord, go up or down a step, then back to the first. That’s a neighbor tone. The syllable birth in the crime against humanity called “Happy Birthday” is an upper neighbor. See? It’s right next door.

Go down instead of up and you have a lower neighbor, a lа̀ Jurassic Park:

0:07

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=msimASAXoys” parameters=”start=171 end=178″ /]

Here’s the Jurassic melody with the neighbors marked:

And when Whitney Houston sang And ahhhhh-eee-yaaaii will always love yooou, the “eee” was an upper neighbor.

You get the idea.

I wanted one more neighbor tone for this post, so I started singing the lower neighbor pattern to myself, like the three Jurassic notes, to see if anything popped into my head. Dah-dah-dah, I sang.

Dah-dah-dah, dah-dah-dah, I sang, then a little faster. DAH-dah-dah DAH-dah-dah.

Wait.

Oh my god, no way.

And also OF COURSE.

The theme to Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood…is absolutely brimming with neighbors.

You think this is a coincidence, I can tell. Let’s just see about that.

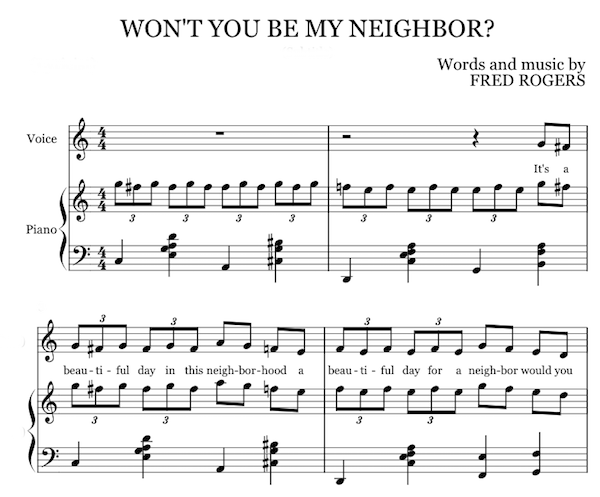

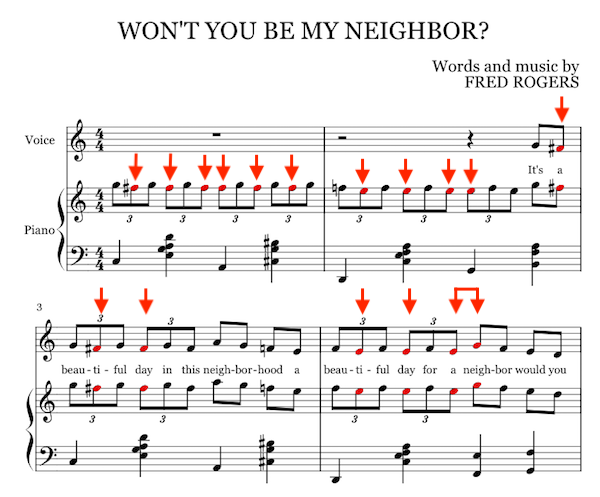

Fred Rogers wrote the words and lyrics himself in 1967. He changed it a bit for the show — more on that below — but fortunately his original arrangement is still in publication, so we can see his intent. I’ve transposed the first four bars to the key he sang in the show:

It’s not surprising that he wrote his own theme song — Rogers’ 1951 bachelor’s degree was in music composition. And when somebody with a degree in music composition writes a song with the word “neighbor” in it 6,000 times and includes neighbor tones in the melody, that’s no coincidence. It’s easy to imagine his quiet satisfaction at a geeky inside joke that virtually no one would ever get.

Hm. You’re still unconvinced. So this fairly common non-harmonic note pops up a couple of times in the song, you say, big deal. That doesn’t mean it was intentional.

Here are those four bars again with the neighbor tones marked:

Seventeen neighbors in four bars, including a double neighbor on the word neighbor? This is too densely-populated a neighborhood to be a coincidence. This is a music major having fun.

Interestingly, by the time the show premiered in 1968, he ironed most of the neighbors out of the vocal line, substituting a straight line of Gs. Maybe he felt the waggling back and forth got in the way of understanding the words, or that it would be too hard for the kids to sing along at home, especially the way it throws off the accent in the triplets. I can easily see him sacrificing his little inside joke so we could feel more comfortable.

But it isn’t completely gone. In addition to several remaining spots in the vocal, listen to the celeste (0:06-0:10) and the piano (0:24-0:28). Still brimming with neighbors.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eInUUfyqa5o” /]

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

When the Music Doesn’t Trust You

15 min

A few posts back I wrote about mickeymousing, a film scoring technique in which the music closely imitates actions on screen. Good for cartoons and parodies, bad for most everything else. Another usually no-good technique is continuous scoring, also known as wallpaper.

Wallpaper is film music that never seems to shut up. Instead of trusting the audience to know how to feel, it nudges and winks every time the emotion turns even slightly — Ooh see? It’s happy. Oh, now it’s sad. Oh! He surprised her. The genre films of Hollywood’s “Golden Age” (1927 to early 1960s) are notorious for unrelenting wallpaper of the distrustful kind.

High Noon (score by Dimitri Tiomkin) is a classic example. BONUS MOMENT: At 1:50-2:00, as Glinda the Good Witch chastises the sheriff, the movie’s main theme “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling” plays in minor. Five seconds later as she says, “Oh Will, we were married just a few minutes ago,” it switches to major. That may be the hammiest moment in all film music.

1:34

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rm0iEYCUw5I” parameters=”start=58″ /]

Here’s some typical wallpaper from the 1940s — The Strange Woman (score by Carmen Dragon):

1:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNsgtXnukyE” parameters=”start=2716 end=2801″ /]

That kind of wall-to-wall scoring mostly ended in the early 70s. But continuous scoring still makes an appearance, often with great results. When it maintains a single emotional arrow toward a climax instead of shadowing every emotional change, it can be really effective. That’s especially true when the music persists despite emotional shifts in the action, as it does in this stunning scene from There Will Be Blood (main score by Johnny Greenwood, this scene by Arvo Pärt):

2:22

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ugTbwvVuLKA” /]

Two small pauses, but still mostly continuous.

Then there’s my favorite, the kind of continuous scoring that serves as a unifying emotional thread through a montage of scene cuts. First this gorgeous, moving sequence, again from There Will Be Blood (Johnny Greenwood):

2:37

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0dlraJXats” /]

Then there’s this heartbreaking thing. Instead of distrust, the continuous scoring plays a crucial part in establishing the emotion — and it takes me to pieces every time I see this film (Love Actually, song by Joni Mitchell):

2:24

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2y-8vxObugM” parameters=”start=72″ /]

Finally there’s the kind that elevates a scene, makes it epic. Repeating and building as it goes, this scoring by Hans Zimmer imbues a few mundane actions — man deplanes, walks through customs, arrives at house, greets children — with power and significance (Inception):

3:42

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQPy88-E2zo” /]

Follow Dale on Facebook:

Mr. Rogers and that Mind-Blowing Jazz Piano

Seeing the documentary “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” on the life and work of Fred Rogers reminded me of two things I sometimes forget:

1. There is genuine goodness in the world.

2. A mind-blowing pianist is for some reason playing absolutely top-shelf jazz as Mr. Rogers changes his shoes.

I’ll leave the goodness to others. Let’s talk about that piano.

Rogers hired Pittsburgh jazz pianist Johnny Costa (who was called “the white Art Tatum” by the black Art Tatum, aka “Art Tatum”) as his musical director. Costa said yes because Rogers offered him the exact amount of his son’s college tuition — which, as the father of three kids halfway through college, I So Get. But Costa had a condition: he wanted to play sophisticated music instead of kiddy stuff, believing that kids could handle it. Rogers was an accomplished pianist himself, and not condescending to kids was a big part of his philosophy, so it was not a hard sell.

But jazz in general is one thing. What actually happens in the opening theme of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood is seriously great jazz.

0:00-0:14 He opens on a celeste, the magical bell piano you have already met in Harry Potter. Already there are some gems, like the jazz chords at 0:07 and 0:10. At 0:11 you get those three sweet melting chromatic chords, very nice.

At 0:32 , the celeste hands off to a jazz trio as Fred enters, laying back to not eclipse the entrance, but still delivering gorgeous piano-lounge jazz.

Then the real fun starts. 0:43-0:50 is just so subtle and tasty, with the piano doing that straight-against-swing thing that’s so hard to master. He improvises the melody in such a way that it dances with Rogers’s singing, overlapping the lyrics but saving more complicated gestures for the spaces in-between — the kind of listening you only get from a skilled jazz collaborator.

But it’s the closing flourish at 1:22 that goes seriously Art Tatum and is so Italian-Chef-Kissy-Fingers perfect it makes my eyes water.

Enjoy.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eInUUfyqa5o” /]

Need more convincing? Check out these closing credits (h/t Gary Gibson):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cY70y_g20GA” /]

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

When Film Music is a Mickey Mouse Operation

Studying film scoring at UCLA was the musical experience of my life. For a full year we wrote to scene, furiously scribbled out the parts, had them played by pros and critiqued by actual film composers, then on to the next and the next. It was practical, intense, and insanely great.

For one session, one of us scored a street fight with these intricately-timed percussion hits on every punch, something that’s really hard to pull off. When the instructor Don Ray played it back against the visual, he said, “Okay, see how Matt landed those hits on the punches? That’s mickeymousing.” Two minutes later, “And again, there’s mickeymousing.”

We all nodded, impressed.

The next week was a rooftop chase, and every single one of us included this magical mickeymousing technique. Every action on screen had a corresponding pop in the music.

By the third cue, Don was laughing and shaking his head. “My fault, my fault. I was too subtle. Last week, when I mentioned Matt’s mickeymousing? I didn’t put enough stink on it. IT’S A BAD THING. It draws attention to itself. Don’t do it.”

As the name implies, lining up the score with the small details of the action started with the early Mickey Mouse cartoons, all the way back to Steamboat Willie. But the absolute heyday of mickeymousing was Looney Tunes:

0:42

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mw_9jOBysz4″ parameters=”start=40 end=82″ /]

It isn’t only in animation. Here’s Bill Sikes beating Nancy to death in the otherwise homicide-free musical Oliver:

0:18

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjblvX95Blw” parameters=”start=69 end=87″ /]

By the 1980s, the technique was used mostly for comic effect, like so:

0:54

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lC6dgtBU6Gs” parameters=”start=90 end=144″ /]

And so:

0:52

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eMSIige_JJg” /]

If you’re scoring a coyote sneaking up on a roadrunner, or scoring a parody, or scoring in 1938, mickeymousing is a terrific idea. Otherwise <insert stink here> IT’S A BAD THING.

And yet how perfect is this…

0:31

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4QYcrR4KGU” parameters=”start=22″ /]

Follow Dale on Facebook:

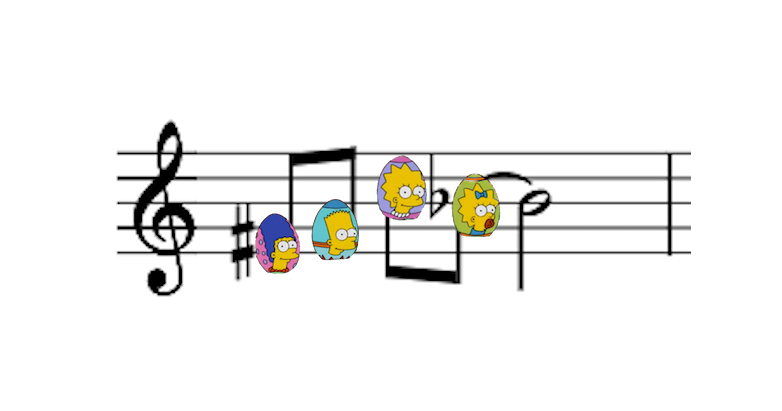

The Real Inspiration for The Simpsons Theme – And No, It’s Not ‘Maria’

5 min

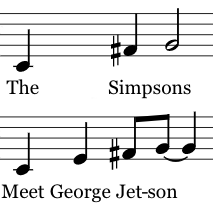

When in the last post I suggested that a trumpet lick in The Simpsons was an homage to “Something’s Coming” from West Side Story, I didn’t mention an even more obvious parallel — that the first three notes of Simpsons exactly equal the first three notes of the main melody of “Maria”:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpdB6CN7jww” parameters=”start=39 end=42″ /]

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1r2EbNSymjE” parameters=”start=2 end=5″ /]

Here’s why I left it out: Unlike the trumpet lick, the opening of the Simpsons theme was definitely not inspired by “Maria.” Elfman was paying tribute to something, but it wasn’t West Side Story. It was The Jetsons.

Back in the 1990s, if a producer really really liked a composer, he would give him a mix tape. As The Simpsons was in development, Matt Groening gave Danny Elfman a tape with all of his favorite cartoon music. He loved the music for Warner Bros. cartoons and Tom & Jerry, but he didn’t want to use that technique known as “mickeymousing” in which the music closely parrots the action on screen. That left Hanna Barbera, including Groening’s favorite cartoon theme of all: “I loved The Jetsons theme the best,” he said.

In no time, Elfman cranked out an iconic theme with a headmotive that bears a striking resemblance to his boss’s favorite:

Also not a coincidence: both are in that unusual Lydian dominant mode I banged on about last time — 4 up and 7 down.

Oh but that’s not all. The whole Simpsons opening sequence is an inside-out parody of The Jetsons opening sequence. In The Jetsons, you start with blue sky and Dad driving away from home. Two kids go to school, then Mom goes shopping, then Dad arrives at work. In The Simpsons, you start with blue sky and Dad driving FROM work, Mom leaves the store, the kids leave school, and they all converge at home.

Both openings are below. For maximum fun, play them at the same time. For more convincing, listen to the short Groening interview below.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1r2EbNSymjE” /]

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eSptqzfTSSE” parameters=”start=8 ” /]

Here’s the smoking gun:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UthzUr0rFQ” /]

Feature image Ludie Cochrane CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Could it Be? Yes It Could! Simpsons Coming, Simpsons Good

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

It jumped out at me the first time I saw the show, probably 1990, and I was immediately convinced that composer Danny Elfman meant to do it. This morning I decided to find his email address to ask him.

In the process of looking for his email, I learned that Elfman’s violin concerto Eleven Eleven just premiered at Stanford’s Bing Hall, and realized that asking him about the goddamn Simpsons theme is like saying “Hello? Is it me you’re looking for?” into Lionel Ritchie’s answering machine, and I recognized that The Simpsons is the equivalent of a catchphrase for Elfman, a good thing that you spawned long ago that continues to nip at your heels for the rest of your life, and that asking about The Simpsons instead of Eleven Eleven in 2018 is like walking up to De Niro on the street and saying, “You talkin’ to me?” and thinking one’s self very clever, so I stopped looking for his email address.

But still, there’s this Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

First you need to know that The Simpsons theme is not in major or minor. It’s in a mode called Lydian dominant. Start with a major scale, then raise the fourth step and lower the seventh, like so:

You’ve heard music in some form of Lydian mode a million times, mostly in movies and musicals. It tends to convey goofiness when fast, childlike wonder when slow. The Simpsons is an example of the fast and goofy; here are two from the childlike wonder department:

(8 sec)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZTbn97-Wws” parameters=”end=08″ /]

(16 sec, and you’ll wish for more)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_t98LWNwUhI” parameters=”start=96 end=113″ /]

Now to the Easter egg. It’s the trumpet lick at 51 seconds:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xqog63KOANc” parameters=”start=51 end=53″ /]

A very distinctive little motive, innit, including both of those unusual Lydian dominant pitches. In fact, I’m pretty sure I’ve only heard that exact thing in one other place. Listen to Tony from West Side Story when he sings the words “maybe tonight” twice at 2:43:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xu7sRdRrm_w” parameters=”start=162 end=169″ /]

Those exact pitches in that exact shape and rhythm, appearing by chance in The Simpsons? Naw. It’s homage, I tells ya, homage. But only Danny Elfman knows for sure, and I’m not asking.

3 Ways the ‘Office’ Theme IS Michael Scott

Michael Scott, the hapless regional manager in The Office, is one of the great characters in television. That mix of blustering confidence in his mouth and self-doubt in his eyes is a picture of striving lameness — a mediocrity who has somehow convinced circus management he’s a high-wire walker, then suddenly finds himself 50 feet above a pit of flaming tigers, naked, deciding whether to spend the surplus on a new copier or chairs.

Steve Carell captures this perfectly in the character of Michael Scott. The show’s theme manages to do the same in music, three ways in 30 seconds.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/uyIVAm9PVrI” /]

1. Dat accordion

First there’s the choice of instrument for the melody. When an accordion is going full tilt boogie, chords and all, it can be incredible. But a single, reedy, wheezy little solo accordion line is the essence of striving lameness, reaching for Van Gogh’s Starry Night and managing only a velvet Elvis. It is Michael Scott.

2. Dat clash

The second is less obvious but even more important. Here’s where the accordion enters in measure 5. Top line is the accordion; middle line is piano; bottom line is bass:

The chord progression is simple: G-Bm-Em-C, almost but not quite the four chords every pop song is made of. Here it is simplified to block chords:

Something weird happens in the second bar. See how the wheezy accordion in the top line hangs on a G from the previous bar? Now look at the harmony in the second bar — specifically the lowest note in the middle staff. It moves from G in the first measure to F# in the second, even as the accordion hangs on G up above. The harmony is right — it’s a B minor triad. But Accordion Michael Scott is oblivious to the fact that the harmony changed beneath him. Because of course he is.

If they had both hung on and changed at the same time, it might have been a pretty thing called a 6-5 suspension. Instead, for two full beats we get G and F# mashing against each other like Steve and Melissa at the 25th reunion.

I’ll isolate those two lines and draw them out with a good trumpet patch in the audio:

Audio:

Hear that clash in the second bar? It’s intentionally wrong. It’s hamfisted and lame. It’s Michael Scott. And it happens twice in eight bars.

3. Rock on

So what do you do if you’re Michael Scott and you’ve just done something hamfisted and lame, twice? You double down, cue the drummer, and rock on:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/uyIVAm9PVrI” parameters=”start=15″ /]

THAT is the most Michael thing of all.

Follow on Facebook:

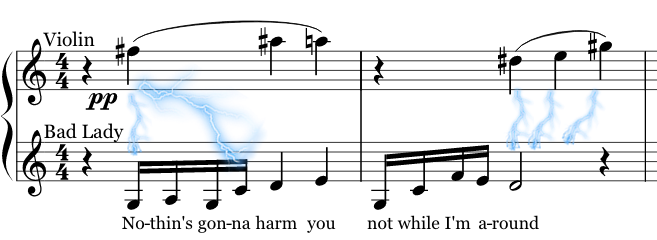

Yeeeah, Something’s Gonna Harm You – Sweeney Todd

5 min

Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd just reappeared on Netflix streaming, and within two days I had a reader question about it:

Q: In Sweeney Todd, at the end of the scene where Toby sings Nothing’s Gonna Harm You to Mrs. Lovett, she sings it back to him, but the music is suddenly making my flesh crawl when she does. What the heck is going on?? – Wendy T.

Oh Wendy. I know the scene.

The music in Sweeney Todd is phenomenal and the lyrics among the most inventive Sondheim ever wrote. And that’s saying something for the guy who came up with

I like the isle of Manhattan

Smoke on your pipe and put that in

THE SCENE: Little Toby has realized Mr. Todd is up to no good, and he’s worried about Mrs. Lovett, without whom he’d be living in a Dickens novel — and not the What-day-is-it-today, delightful-boy, bring-me-that-goose-and-I’ll-give-you-a-shilling part.

Toby sings “Nothing’s gonna harm you / Not while I’m around” to a trite melody that mirrors his naiveté. We know something that Toby does not: Mrs. Lovett is a willing accessory to Sweeney Todd’s crimes, guilty right up to her meat pies.

While Sweeney has been driven to a murderous spree by a missed chance to kill the judge who ruined his life, Mrs. Lovett is only in it for the filling. So when Toby goes all Oliver Twist on her, you can see her soften a little.

Mid-scene, Toby sees something that confirms his suspicions about Mr. Todd — the coin purse of his missing and presumed-dead master — and he flips out. To calm him, Mrs. Lovett sits him down and sings the same protective song that Toby sang to her. But we know, from the music alone, that she has decided to kill the boy.

Watch the whole scene for the full effect. The skin-crawl starts at 2:48:

3:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/LssWKaDF9bk” /]

What’s Going On

The music is identical to Toby’s song with one addition: a quiet violin line high above the voice. While Mrs. Lovett is singing in C major, the violin is playing an atonal melody, meaning the notes don’t really fit into any key — the musical equivalent of insanity. As a bonus, the particular notes he chose are creating strong dissonances with the melody — ninths, sevenths, tritones.

Sondheim doesn’t need to hit you over the head — just six quiet disordered notes tell you how different Mrs. Lovett’s thoughts are from her words. If the lines were in the same octave, it would be harsh and unsubtle. By instead putting two octaves of air between them, Sondheim makes your skin crawl.

Is there a piece of music you love or hate but don’t know exactly why? A moment that makes you laugh or cry? Be like Wendy. Submit a question here!

Click Like below to follow on Facebook…