Could it Be? Yes It Could! Simpsons Coming, Simpsons Good

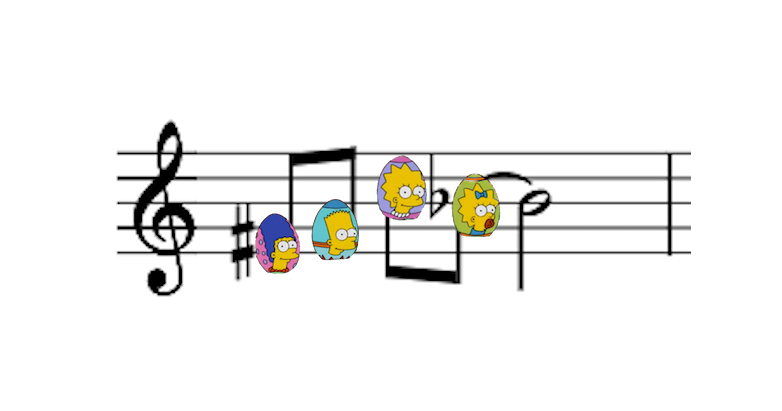

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

It jumped out at me the first time I saw the show, probably 1990, and I was immediately convinced that composer Danny Elfman meant to do it. This morning I decided to find his email address to ask him.

In the process of looking for his email, I learned that Elfman’s violin concerto Eleven Eleven just premiered at Stanford’s Bing Hall, and realized that asking him about the goddamn Simpsons theme is like saying “Hello? Is it me you’re looking for?” into Lionel Ritchie’s answering machine, and I recognized that The Simpsons is the equivalent of a catchphrase for Elfman, a good thing that you spawned long ago that continues to nip at your heels for the rest of your life, and that asking about The Simpsons instead of Eleven Eleven in 2018 is like walking up to De Niro on the street and saying, “You talkin’ to me?” and thinking one’s self very clever, so I stopped looking for his email address.

But still, there’s this Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

First you need to know that The Simpsons theme is not in major or minor. It’s in a mode called Lydian dominant. Start with a major scale, then raise the fourth step and lower the seventh, like so:

You’ve heard music in some form of Lydian mode a million times, mostly in movies and musicals. It tends to convey goofiness when fast, childlike wonder when slow. The Simpsons is an example of the fast and goofy; here are two from the childlike wonder department:

(8 sec)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZTbn97-Wws” parameters=”end=08″ /]

(16 sec, and you’ll wish for more)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_t98LWNwUhI” parameters=”start=96 end=113″ /]

Now to the Easter egg. It’s the trumpet lick at 51 seconds:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xqog63KOANc” parameters=”start=51 end=53″ /]

A very distinctive little motive, innit, including both of those unusual Lydian dominant pitches. In fact, I’m pretty sure I’ve only heard that exact thing in one other place. Listen to Tony from West Side Story when he sings the words “maybe tonight” twice at 2:43:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xu7sRdRrm_w” parameters=”start=162 end=169″ /]

Those exact pitches in that exact shape and rhythm, appearing by chance in The Simpsons? Naw. It’s homage, I tells ya, homage. But only Danny Elfman knows for sure, and I’m not asking.

Porn for Music Theoryheads

(18 min and worth it)

To a certain kind of musician, the deathbed dictation scene from Amadeus was everything:

It was a courageous scene to even try. “Second measure, fourth beat on D. All right? Fourth measure, second beat – F!” is not generally Academy-bait banter, as Tom Hulce notes in this great behind-the-scenes clip:

And now, after thinking that scene couldn’t get any better, I stumble on this brilliant gem. For an even smaller subset of musicians — the kind that likes to peel back the skin and see the gleaming bones — this is just porn:

(Extra Credit: Find the theory error in the dialogue and put it in the comments.)

Friends Don’t Let Friends Clap on 1 and 3

In a post called The (Actual) Evolution of Cool, I described the difference between cool and non-cool music using Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition” and a Sousa march. TL;DR: Putting the emphasis in unexpected places tickles the cerebellum’s timekeeper, which simulates danger, which feels cool.

One way to inject the unexpected into music is by emphasizing the offbeats. If a song has four beats per measure, as most do, beats 1 and 3 are strong beats, the obvious places to put your emphasis. Polka bands, marches, and hymns all emphasize 1 and 3.

But if you want to be even cooler than a hymn, throw the emphasis to the offbeats — one-TWO-three-FOUR.

Harry Connick Jr. is a cool guy, but his audience is mostly white suburban moms, sorry, which means the clapping is gonna be on 1 and 3, which kills the feels. And the particular kind of New Orleans jazz he plays can teeter between cool and square, so a little push from the wrong side of the beat is death.

The concert clip below starts with 40 seconds of painful 1-3 clapping, and sure enough, Connick’s piano sounds rinky dink. But right at 0:40 Connick adds a beat, turning one of the four-beat measures into a five-beat measure. The audience just keeps clapping on every other beat, but now they’re on 2 and 4, and everybody wins. You can see the drummer exulting in the background when he realizes that Connick saved the swing:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UinRq_29jPk” /]

Genius move.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

h/t Rob Tarr | Top image by Stephanie Schoyer Creative Commons 2.0

Title inspiration via Drummer’s Resource

The Long Exile in Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah

When Leonard Cohen died at 82, he left us more than 100 songs, most of which I don’t know. But there’s one that’s almost universally known and adored: “Hallelujah.” One reason for that success is an effective use of the tools of harmony.

Start by listening to the first verse and chorus (58 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/Qt2FWAbXinY” parameters=”end=58″ /]

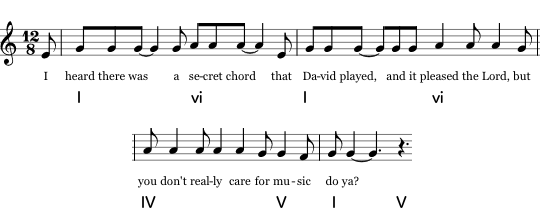

Let’s take it apart a bit. We’re in C major, so the tonic chord, the emotional home, is a C triad (I). Here’s the first phrase with Romans:

That’s a comfortable, homey phrase of music. The melody winds around G, the reassuringly stable dominant pitch. The harmony is also fully domesticated, touching home (I) three times and the dominant (V) twice. We’re 15 seconds in, and all is well.

The chords at the end of a phrase make up a kind of emotional punctuation called the cadence. This phrase ended on V, which is common. It’s called a half cadence, the musical equivalent of a comma. There’s an unresolved, up-in-the-air feeling because you’re pointing home without actually going home (7 sec):

Feel the dangle? That’s a half cadence.

Now before we get to the magic, let’s geek out on some music theory Easter eggs Cohen has hidden in the next phrase:

“The 4th” is over a IV chord; “the 5th” is over a V; “minor fall” is a minor triad and “major lift” is a major triad. That’s adorable.

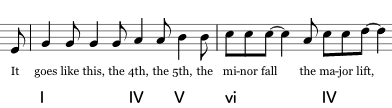

For the real magic, we need to zoom out and look at eight measures:

The melody forms a beautiful, yearning arc, starting from middle E (“it goes”), reaching up to high E (“composing”), then falling through more than an octave to middle C on the last Hallelujah. Here it is simplified:

Gorgeous. But as usual, it’s the harmony that conveys the main emotional story.

(Stick with me now. This is cool and comprehensible, and a good window into how music works.)

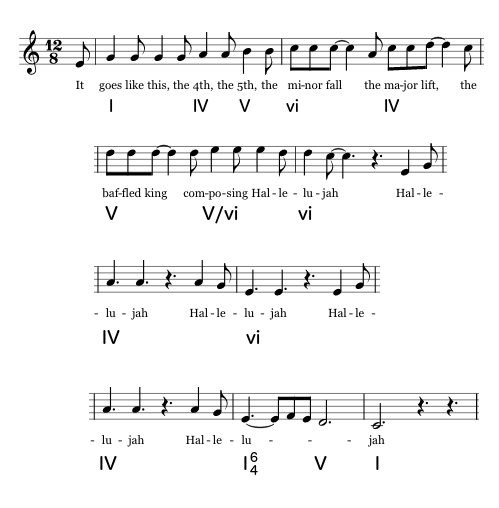

Remember how the first 4-bar phrase kept coming home to the tonic? I -vi-I -vi-IV-V-I? That made it homey and comfortable. Now look at the chords for these next two phrases — 8 long, slow bars:

I IV V vi IV V V/vi vi | IV vi IV I6/4 V I

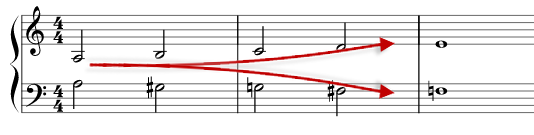

We leave home (I) on “It goes like this,” then wander in exile for what is (musically speaking) a very long time. Along the way, we keep encountering LIES. The third chord is a V (on “the 5th”), which promises home…but instead of I , we get pulled sideways to vi, the minor. That’s disconcerting, but okay.

Two chords later there’s another V, another promise of home. But the chord after it — the one that looks like a fraction — isn’t even in the key! A minor chord in our home key has been changed into a major chord, becoming a dominant arrow for another key entirely. It’s called a secondary dominant. In this case it’s the dominant of A minor (vi), which leads strongly to vi. Going from V to vi is called a deceptive cadence , for good reason: it’s a damn lie.

The first vi was disconcerting. The second, stronger one is more so. Twice we were promised our C major home, and twice we ended up on A minor instead. The second one was even tonicized, which is what you call it when a dominant of its very own was created to emphasize it.

As we head into the chorus (“Hallelujah…”), we get a IV. Ooh, I know this one! It could be the first part of a plagal cadence (IV-I), also known as the “amen” because it closes every church hymn. That’ll take us home through another door, like so — and I’ll make it nice and churchy (11 sec):

Amen, see? That would have grounded the phrase and ended our exile. But…it doesn’t do that. We don’t go home. Instead, the IV goes unexpectedly to vi, and we’re pulled sideways to the A minor dark side for a THIRD time (11 sec):

The first one takes us home and tucks us into our bed; the second pivots to our dark minor lake cabin in winter, and the firewood is wet, and the horn just blew three times.

At this point it’s been a full 30 seconds since we’ve been home, an eternity on this scale. Worse still, we’ve been teased with home three times. Cohen has us feeling subconsciously homesick. Then finally, finally, we get a V that isn’t a lie. It promises home and delivers, moving to a I on the last syllable of the last Hallelujah. It’s an authentic cadence, V-I, the musical equivalent of a period, full stop.

Here’s my favorite cover of the song. Feel the security of that first phrase, then leave home, wander in the desert as home is thrice denied, then feel the return on the last Hallelujah of the chorus. Beautiful.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y8AWFf7EAc4″ parameters=”start=69″ /]

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Top image by Bill Strain | CC 2.0

Lou Rawls and the Christmas Clams

I hate to do this.

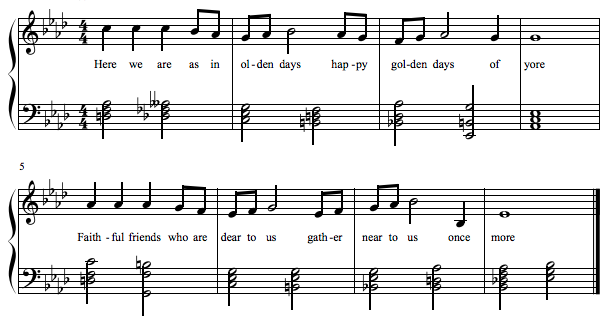

Lou Rawls is one of my favorite R&B singers. “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” is one of the most harmonically delicious Christmas songs. So you’d think the Lou Rawls cover of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” would make me happy. But it doesn’t — all because of one phrase.

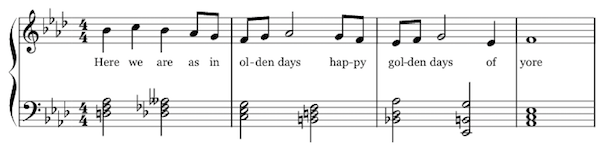

I know this is a little stupid. Most of the cover is perfection. The band is tight, and Lou is on his game. I’m having myself a merry, as requested. But just over a minute in, on “faithful friends who are dear to us,” Lou lays down a series of clams so painful that I want to gently place my fingertips on the crowning head of baby Jesus and stuff him back in.

Let’s listen from the beginning, up to the spot that pees on my Yule log (75 sec):

The harmony in this song is rich and gorgeous, especially in the bridge:

It’s taking all of my restraint to not run naked and giggling through the Romans on this one. Those of you who would understand it can do the analysis your own fine selves. For the rest, here’s a slow jam on the harmony (32s):

It’s taking all of my restraint to not run naked and giggling through the Romans on this one. Those of you who would understand it can do the analysis your own fine selves. For the rest, here’s a slow jam on the harmony (32s):

A lot of the wonder in this passage is in the relationship of the melody to the harmony. There’s a chain of dissonances that still play by the rules of harmony. The bass note and melody note form one dissonant interval after another — sevenths and ninths and tritones. But in the context of the full harmony, every note of that tune is either part of the chord or what’s called a non-harmonic tone — a note that’s not in the chord of the moment, but follows one of a dozen established patterns that your ear can make sense of. This passage was not written overnight. Picture one of those guys who paints landscapes on the head of a pin.

If you’re a jazz singer, futzing around with the melody is part of the job description. But when the harmony is as complex as this, it’s a lot harder to thread that needle. Rawls starts the bridge like so:

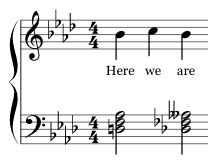

I’ve straightened out the rhythm for comparison to the original, but notice the pitches. Instead of singing three Cs for “Here we are,” he sing Bb-C-Bb. Nice touch. He’s now off by one step for the rest of the phrase…

…and it works anyway! Jazz harmony is greatly expanded compared to classical harmony. Instead of three-note triads, you have 7th chords (with 4 notes), 9th chords (with 5 notes), and so on. More pitches are eligible to sound at any given moment. You can go off script and still win, and that’s what he did here. Every melody note nestles into its chord as either a chord tone or a legal non-harmonic. To translate that to jazz, Lou laid no clams in those four bars, only pearls.

Oh, but the next two bars.

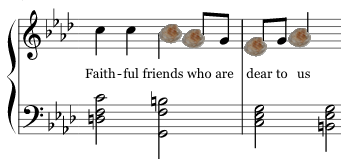

Flush with that victory, Lou decides to sing the same basic phrase again. But the harmony under it has changed, a lot. The result is a clambake:

You don’t need to be a music theorist to hear it. Here they are together: listen to how the first phrase works, and the second phrase (“Faithful friends”) doesn’t (15 sec):

<silent scream>

I know what you’re thinking. I’m a petty little man, and he’s Lou Rawls. But imagine that for years you’ve adored the genius that went into one tiny corner of a beautiful painting, a detail that no one else seems to notice or comment on. Then one day you see someone walk by and squirt their clam sandwich onto that exact spot. I don’t care if it was Michelangelo himself who bit the sandwich, you’re still gonna be pissed.

I love you Mr. Rawls, but dude, napkin.

Why is That iPhone “Don’t Blink” Ad So Damn Cool?

I don’t care about the headphone jack. Listen to the music:

Almost every part of the ad score is variations on a single rhythm — that Bump. Bump. Bump, bump, a-CHAK you hear in the opening seconds. It’s a cool rhythm. But what’s cool about it?

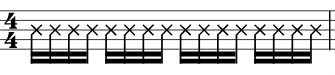

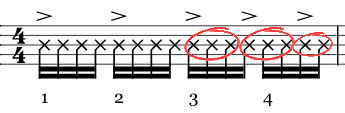

It’s not pitch. This is mostly about rhythm, the division of time into bits. If you have four beats per bar and divide each of them into four 16th notes, you can think of the bar as having 16 available slots. In each one, you have a choice: hit the drum, or hit it hard (accented), or do nothing. 16 slots, 16 choices in each bar:

Just as melody and harmony draw on 12 available pitches, most rhythm (in 4/4, the most common meter) is created from grouping these 16 clicks. In this case, it’s 4+4+3+3+2:

1234 1234 123 123 12

Two groups of 4, then two groups of 3, then a group of 2. This has the effect of establishing a steady beat (1234 1234), then throwing you off balance a bit (123 123 12), then returning to steady in the next bar (1234 1234). On top of that, there’s a feeling of acceleration as the groups get shorter.

The combined result is two confident steps, then trip-tumble forward a little, then a smooth recovery into the next measure.

Okay, bad example. More like this:

We’ve been here before, in the post on The Evolution of Cool:

Our cerebellar timekeeper determines how regular a sound is. If it stays predictable — dripping water, chirping crickets — we feel confident and secure. If it becomes less predictable or changes in intensity, we feel unsettled, possibly threatened.

The beats [of a Sousa march] are regular. Your cerebellum is tapping its foot, predicting every beat, right on the money. It makes you feel safe, confident, in control, but no one would call it cool.

The Sacrificial Dance from The Rite of Spring is jerky and angular, with unpredictable rhythms and sudden changes in intensity — the musical embodiment of anxiety and terror. Your cerebellum is freaked out by the utter inability to predict the next note. The music is doing what it’s supposed to do, but you wouldn’t call it cool.

The music we identify as cool splits the difference, combining a steady predictable beat with unpredictable departures from that beat. It’s flirting with the remote sense of danger without actually endangering you.

If music establishes a beat, then throws you around a bit — backbeat accents, unexpected hits around the beat, changing patterns — it gives a little thrill to your cerebellar timekeeper, tickling that part of you that listens for the irregular sounds of danger, then pulling you back to the safety of a steady beat before dangling you over the cliff again.

The ad throws a few extra stumbles in to keep you off balance on the larger scale. Start tapping right at the beginning and keep it rock steady. You’ll feel yourself trip over a notch in time around 4 seconds:

Feel that?? One extra 16th rest was inserted, a single click in time, throwing you behind the beat. That gives your cerebellar timekeeper a little thrill. That’s cool.

Yeeeah, Something’s Gonna Harm You – Sweeney Todd

5 min

Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd just reappeared on Netflix streaming, and within two days I had a reader question about it:

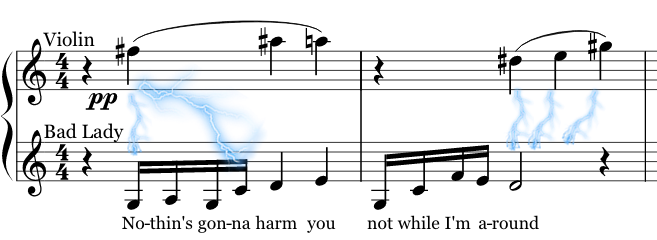

Q: In Sweeney Todd, at the end of the scene where Toby sings Nothing’s Gonna Harm You to Mrs. Lovett, she sings it back to him, but the music is suddenly making my flesh crawl when she does. What the heck is going on?? – Wendy T.

Oh Wendy. I know the scene.

The music in Sweeney Todd is phenomenal and the lyrics among the most inventive Sondheim ever wrote. And that’s saying something for the guy who came up with

I like the isle of Manhattan

Smoke on your pipe and put that in

THE SCENE: Little Toby has realized Mr. Todd is up to no good, and he’s worried about Mrs. Lovett, without whom he’d be living in a Dickens novel — and not the What-day-is-it-today, delightful-boy, bring-me-that-goose-and-I’ll-give-you-a-shilling part.

Toby sings “Nothing’s gonna harm you / Not while I’m around” to a trite melody that mirrors his naiveté. We know something that Toby does not: Mrs. Lovett is a willing accessory to Sweeney Todd’s crimes, guilty right up to her meat pies.

While Sweeney has been driven to a murderous spree by a missed chance to kill the judge who ruined his life, Mrs. Lovett is only in it for the filling. So when Toby goes all Oliver Twist on her, you can see her soften a little.

Mid-scene, Toby sees something that confirms his suspicions about Mr. Todd — the coin purse of his missing and presumed-dead master — and he flips out. To calm him, Mrs. Lovett sits him down and sings the same protective song that Toby sang to her. But we know, from the music alone, that she has decided to kill the boy.

Watch the whole scene for the full effect. The skin-crawl starts at 2:48:

3:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/LssWKaDF9bk” /]

What’s Going On

The music is identical to Toby’s song with one addition: a quiet violin line high above the voice. While Mrs. Lovett is singing in C major, the violin is playing an atonal melody, meaning the notes don’t really fit into any key — the musical equivalent of insanity. As a bonus, the particular notes he chose are creating strong dissonances with the melody — ninths, sevenths, tritones.

Sondheim doesn’t need to hit you over the head — just six quiet disordered notes tell you how different Mrs. Lovett’s thoughts are from her words. If the lines were in the same octave, it would be harsh and unsubtle. By instead putting two octaves of air between them, Sondheim makes your skin crawl.

Is there a piece of music you love or hate but don’t know exactly why? A moment that makes you laugh or cry? Be like Wendy. Submit a question here!

Click Like below to follow on Facebook…

That Time Stravinsky Aimed a 7th Chord at America!

A n article that crossed my Facebook last week tapped the most powerful human emotions — threatened national pride, the fear of the tall and balding, and that ancient, visceral distrust of 7th chords.

While guest conducting the Boston Symphony in 1944, the composer Igor Stravinsky programmed his own arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as a tribute to his newly-adopted home.

It didn’t go well:

As you might expect, Stravinsky’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” wasn’t entirely conventional, seeing that it added a dominant seventh chord to the arrangement. And the Boston police, not exactly an organization with avant-garde sensibilities, issued Stravinsky a warning, claiming there was a law against tampering with the national anthem. Grudgingly, Stravinsky pulled it from the bill.

Make sure you’re on a secure server before you listen to Stravinsky’s illegal arrangement (1:54):

(Those are dominant 7th chords at 0:21, 0:42, 1:15, and 1:30.)

The arrangement is incredibly tame, especially for Stravinsky, and light-years from anything that can be called “avant-garde.” Oh sure, he threw in some interesting non-harmonic tones. But the fact that it’s only in one key at a time makes it one of the most conventional things Stravinsky ever wrote. Whether it was wildly unconventional for 1944 (nope) or for the Boston Symphony in 1944 (nope) or for a setting of the National Anthem (barely) is not that interesting to me. It was unusual enough to get the attention of the Boston PD, which is funny and apparently did happen. Stravinsky was fined $100 under a misapplied interpretation of a dumb but actual Massachusetts statute.

As weird as all that is, one detail of the article got my attention:

Stravinsky’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” wasn’t entirely conventional, seeing that it added a dominant seventh chord to the arrangement.

Oh fer…okay. Where to start.

Music is a mystery to most people, I get that. But there’s a common tendency to not even try, and to assume that the not-trying won’t be noticed. A film that painstakingly researches whether a particular style of eyeglasses was available in 1924 before putting them on the face of an extra in the distant background will nonetheless focus on a clarinetist tootling away in a jazz band with his hands reversed on the instrument — even though the set of all former middle school clarinetists must surely outnumber the set of all eyeglass-period-style-knowers. And when an otherwise brilliant montage in the movie Stardust has Tristan playing an audible major triad while the actor presses three random keys — something inside me dies.

Yes I know, starving children and all.

The story of Stravinsky’s felonious dominant seventh is even weirder than a careless error, like not knowing the clarinetist’s left hand is on top. Instead, it’s of the “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” type. The arrangement does include a dominant 7th — several, in fact. But you’d be hard-pressed to find an arrangement of our national anthem that doesn’t include a dominant 7th. Or 95% of anything written since 1690. It’s one of the most common chords in Western music.

Here are the Beatles outlining a dominant 7th from the bottom up (8 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-VAxGJdJeQ” parameters=”start=86 end=94″ /]

It is as conventional a chord as you can imagine.

That’s not to say it isn’t a great and useful chord. Remember when I used the Batman (movie) theme to show how unstable pitches yearn to resolve by the shortest distance they can, like a half step? Good times.

And remember the one about tritones being deliciously unstable? They are.

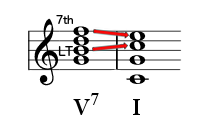

Well check this out: When you add the 7th to a regular triad — the top note in the first chord below — you get a note that’s unstable, yearning to drop a half step to a stable note in the tonic chord that follows. The leading tone (Dorothy’s “Why oh why caaaan’t…”) is already yearning to go up a half step to the tonic pitch. And, AND, those two notes together (B and F in this case) form the awesomely unstable tritone, the ‘devil in music’!

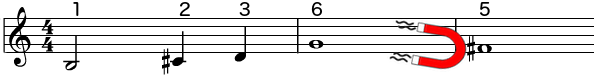

If the plain old dominant triad (V) works like a magnet to the tonic home, then the dominant seventh chord (V7) is an electromagnet. To the already neon arrow of the dominant triad, it adds the downward pull of the 7th AND the instability of the tritone. First I’ll outline the seventh chord (or the left), then play V7 moving to I:

Scandalized? More likely you’re surprised by how unsurprising it sounds. That’s the point. For all that useful instability, the V7 is about as typical and boring a musical thing as you can get.

And you know who specialized in not using ultra-conventional things like V7 chords?

Stravinsky.

So to say Stravinsky’s use of a V7 was somehow “avant garde” is like saying Picasso freaked out artistic sensibilities by painting one nose per face. It is the opposite of the way he challenged norms.

The use of a fancy-pants term is also part of this game, so a better comparison is finding out there’s ‘dihydrogen monoxide’ in your swimming pool, or that a poet was caught using an ‘interrogative’. It’s like saying Guy Fieri shook up the cooking world by using ‘sodium chloride’ on eggs. The only way your surprise needle moves is if the fancy term (in this case, ‘dominant 7th’) is new to you.

So whether or not Stravinsky was guilty of assaulting our national anthem, the dominant 7th chord wasn’t involved in the crime. Of course its fingerprints were on the anthem. That’s because it lives there. And everywhere else.

How One Note Turned David Cameron to the Dark Side

- July 31, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

Walking from the lectern after announcing his intention to resign as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Cameron did something funny: he sang a happy little tune to himself.

Well, he thought he sang it to himself. His mic was still live, so he actually sang it to the whole world:

I don’t know what he meant to sing, if anything — but this is roughly what came out:

Some thought they heard a bit of the West Wing theme in that ditty, while others heard the first notes of the overture to Tannhäuser. Both were wrong in a way I’ve mentioned before. Like the alien House of Cards cue, Cameron is actually singing a bunch of 4ths — Up a 4th, down a 4th, down another 4th. The ear has a little trouble sorting that out, so we fudge the unconventional notes to form a triad instead. It’s like an aural version of pareidolia, the human tendency to see patterns that aren’t really there. The “face on Mars” is a famous example.

Cameron’s ditty is actually closer to a motif that fans of the original Star Trek will instantly recognize. It’s even in the same key (2 sec):

Push those notes through horns and the effect is heroic. But when those same notes fall from the doughy face of a Prime Minister who just washed his hands of the biggest mess in recent British political history — especially when said notes are wearing the goofy non-lexical vocables doot-doo — it can only mean one thing: I’m a happy little fella.

Chris Hollis, a guitarist in a British pop punk band, had a darker plan for those notes: turn Happy Little Fella into Evil Tory.

That’s hilariously awesome. But how did he turn something so happy so damn dark? The low brass, cellos, and percussion helped, but that’s not enough. If those instruments had played the exact stack-o’-4ths that Cameron sang, it wouldn’t have sounded evil:

So aided by Cameron’s tunelessness, Chris cheated, just a bit, auto-tuning the last note down a half step. As D turns to Db, Gomer Pyle turns to Darth Vader:

That tiny change has a huge effect because of one of the most counterintuitive things in music: pitches that are close to each other on the keyboard (like C and Db) are miles away from each other harmonically, and therefore emotionally.

The tonal center of Cameron’s little tune is C. By fudging the last pitch down from D to D-flat, Hollis creates a strong dissonance with C and turns a 4th (G-D) into a tritone (G-Db), one of the most dissonant intervals. He then harmonizes the whole thing as C minor – Db minor, two chords that are about as far apart harmonically and emotionally as you can get. (More on this when we get to the circle of fifths.)

In a way, Hollis did the opposite of pareidolia: he took something slightly face-like, and instead of nudging it into a face, he made it more like the yawning mouth of hell. The sudden switch from goofy to evil is comedy gold.

Yes, ‘Stairway’ Was Stolen…Just Like Everything Else

- June 26, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

A jury decided that Led Zeppelin did not steal the iconic opening measures of “Stairway to Heaven” from a passage in the song “Taurus” by the band Spirit. Some people think Zeppelin got away with murder, arguing, “Well just listen to it, jeez!”

In fact, they got away with composing.

Whole-cloth ripoffs like “U Can’t Touch This” aside, the idea that it’s wrong to use a string of notes someone else once used in a similar way stems from a modern misunderstanding of how music is created — the unhelpful romantic myth that every new piece of music is a unique snowflake crafted from the purrs of unborn kittens in the soul of the composer.

In fact, nearly every piece of music you love is made up of 99.9 to 100% recycled materials. That’s not an accident: Composers return again and again to the shapes and patterns in our established musical lexicon because that’s what composing is.

Yes, there are exceptions — mostly radically avant garde pieces that try to make a virtue out of keeping you perpetually balanced on the back legs of your chair. That approach leaves a pretty narrow range of emotional states to explore, things like anxiety and puppy-slapping irritation. Once you’ve rejected all shared musical language, you can mostly forget slowly unfolding emotional experience.

To see what I mean, and why the Stairway lawsuit (and Blurred Lines, and Creep, and yes, even My Sweet Lord) was dumb, let’s take a peek into the workshop.

A Big, Finite List

Most Western music derives from a finite number of raw materials. It’s a big number, but still finite. You have 12 pitches arranged into two main scale types (major and minor), with occasional side trips into five others.

Western harmony is based on triads — three notes stacked in thirds. There are four kinds: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. You can also keep stacking thirds, adding a 7th, a 9th, or an 11th to the triad, and so on.

When a pitch sounds that isn’t in the chord of the moment, it’s a nonharmonic tone, of which there are about 12 types — passing, neighbor, suspension, anticipation, and so on.

Pitches arrange themselves over time in meter and rhythm. Each beat can be divided up into smaller bits, usually in 2, 3, or 4 parts, sometimes something stranger like 5. The most common meters are recurring bundles of 2, 3, or 4 beats called measures, sometimes 6, less often 5, 7, 9, or even 33 beats per measure.

Measures are usually in groups of 4 called phrases. Though it’s rare to have a piece based entirely on three- or five-bar phrase lengths, one of the best emotional devices in music is an occasional abbreviated or extended phrase. Nicely messes with your expectations.

The tonic chord usually goes to V or IV, sometimes to iii or vi, less often ii or vii. Mixing the usual with the unusual is the crux of the game.

Different genres of music have certain core instrumentations. A rock band usually has a guitar or two, bass, drums, and vocals. Sometimes a keyboard. Sometimes horns. Sometimes a flute or banjo. Orchestra has ABC, funk band has DEF, polka band has XYZ. So within a certain genre, the choices are even more constrained, and the similarities between pieces multiply.

On it goes, a large but finite set of variables in pitch, meter, rhythm, instruments. The amazing thing is that such an incredible variety of genres and songs has come out of this large but finite set.

Within the choices available are patterns and combinations that produce certain emotional effects — tension, calm, dread, humor, gravity, power, violence, aspiration, momentum, flight. The existing set of musical elements is drawn on over and over by composers to produce these effects in the same way a million writers dip their buckets into the shared well of language, drawing out existing words and phrases and allusions to produce the effects they need.

When writers need to evoke “bittersweet yearning,” they don’t start cobbling together letters into new combinations to see what might feel both bittersweet and yearny. They draw on the large but finite set of words and phrases that have already been used to capture that feeling.

Music works the same way. You want bittersweet yearning? Try a I-iii progression. It’s been done a thousand times, but that doesn’t mean I can’t do it again, a little differently, and create something that is new but (here’s the point) not unique.

The idea that each piece of music arrives fresh from the sea foam like Aphrodite on the clamshell, and that it must evoke no other existing song, is both detached from reality and paralyzing to the songwriter. When I studied composition, I can’t tell you how many times I sat down at the piano to come up with the germ of an idea, plunked out three notes, and said, Nope…Stravinsky. Three more notes: Nope…Bartok. Frustrated silence: Nope…Cage.

It’s a weird modern conceit. Bach did not tinkle out a phrase and mutter, Nee… Buxtehude. Nee…Couperin. Sheiße! Nor did he write music that had already been written. He used and adapted patterns and combinations that almost always had been used before. You use them in new ways, extend them, evolve them — but you don’t set out to utterly avoid every resemblance to what already exists. The whole idea is bizarre. It seems like it’s encouraging originality, but it’s actually deeply anti-creative.

The Case of Stairway v. Taurus

Stairway to Heaven is exactly as “stolen” as everything else you’ve ever heard. When he sat down to write the song, Page drew on existing materials and norms to create something new. Randy California did the same when he wrote Taurus. In the process, they crossed into similar territory for a few bars.

Both started with the commonest clay: 4/4 meter, the key of A minor, and an acoustic guitar outlining the chords in straight eighth notes and four-measure phrases — each choice so common as to be essentially the default.

Then they both chose a device that’s rich and evocative, and not original to either of them: a descending chromatic bass line (going down by half steps). It’s a device so well established that it has a name — the “lament bass” — and variations of it pop up in everything from Bach’s “Crucifixus” to the Beatles’s “Michelle” to “Chim Chim Cher-ee.” Follow that bass line (13 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG6O4N3wxf8″ parameters=”start=7 end=20″ /]

So the descending chromatic bass isn’t default, but it’s a well known device. The question as always is what you do with it. The composer of “Taurus” did this (28 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xd8AVbwB_6E” parameters=”start=44 end=72″ /]

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

Here’s what Page did with the same bass line (27 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9ioyEvdggk” parameters=”end=26″ /]

That’s greatness. In addition to the descending bass, Page laid an ascending scale into the upper line (circled notes). Sometimes a pitch is displaced by an octave or off the beat, but your ear hears the ascending line. This creates a wedge that slowly opens — unison, third, fourth, sixth, and finally that delicious major seventh — before returning to the unison/octave:

I’ve pulled out the lines so you can hear them better:

The result is a nuanced, haunting passage written by an artist who knew what he was doing. And this doesn’t even crack open the inspired work in the next hundred measures. I might come back to that.

So: was Stairway directly inspired by Taurus? Who knows. In a better world, Page could stand up and say, “That’s right, I got the idea straight from Taurus. Then I made it better. That’s how this bloody thing works.” And composers would stop suing other composers for composing.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Full songs: Spirit, Taurus; Led Zeppelin, Stairway to Heaven

Jimmy Page image by Dina Regine via Flickr | CC 2.0

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!