Lou Rawls and the Christmas Clams

I hate to do this.

Lou Rawls is one of my favorite R&B singers. “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” is one of the most harmonically delicious Christmas songs. So you’d think the Lou Rawls cover of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” would make me happy. But it doesn’t — all because of one phrase.

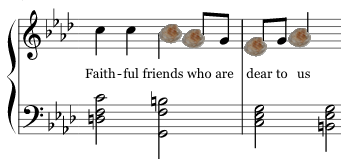

I know this is a little stupid. Most of the cover is perfection. The band is tight, and Lou is on his game. I’m having myself a merry, as requested. But just over a minute in, on “faithful friends who are dear to us,” Lou lays down a series of clams so painful that I want to gently place my fingertips on the crowning head of baby Jesus and stuff him back in.

Let’s listen from the beginning, up to the spot that pees on my Yule log (75 sec):

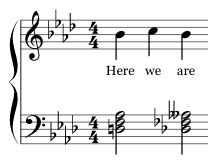

The harmony in this song is rich and gorgeous, especially in the bridge:

It’s taking all of my restraint to not run naked and giggling through the Romans on this one. Those of you who would understand it can do the analysis your own fine selves. For the rest, here’s a slow jam on the harmony (32s):

It’s taking all of my restraint to not run naked and giggling through the Romans on this one. Those of you who would understand it can do the analysis your own fine selves. For the rest, here’s a slow jam on the harmony (32s):

A lot of the wonder in this passage is in the relationship of the melody to the harmony. There’s a chain of dissonances that still play by the rules of harmony. The bass note and melody note form one dissonant interval after another — sevenths and ninths and tritones. But in the context of the full harmony, every note of that tune is either part of the chord or what’s called a non-harmonic tone — a note that’s not in the chord of the moment, but follows one of a dozen established patterns that your ear can make sense of. This passage was not written overnight. Picture one of those guys who paints landscapes on the head of a pin.

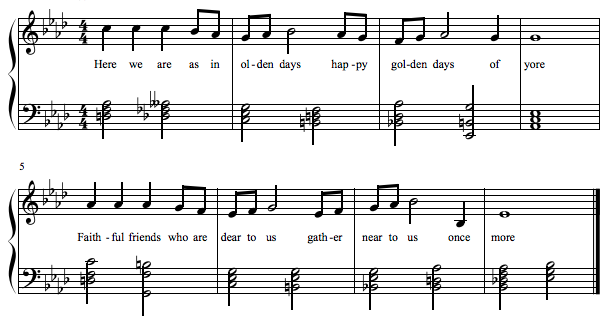

If you’re a jazz singer, futzing around with the melody is part of the job description. But when the harmony is as complex as this, it’s a lot harder to thread that needle. Rawls starts the bridge like so:

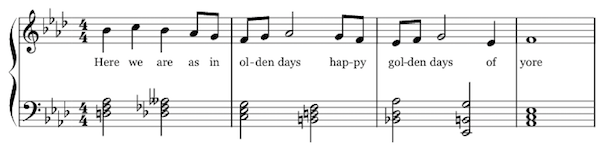

I’ve straightened out the rhythm for comparison to the original, but notice the pitches. Instead of singing three Cs for “Here we are,” he sing Bb-C-Bb. Nice touch. He’s now off by one step for the rest of the phrase…

…and it works anyway! Jazz harmony is greatly expanded compared to classical harmony. Instead of three-note triads, you have 7th chords (with 4 notes), 9th chords (with 5 notes), and so on. More pitches are eligible to sound at any given moment. You can go off script and still win, and that’s what he did here. Every melody note nestles into its chord as either a chord tone or a legal non-harmonic. To translate that to jazz, Lou laid no clams in those four bars, only pearls.

Oh, but the next two bars.

Flush with that victory, Lou decides to sing the same basic phrase again. But the harmony under it has changed, a lot. The result is a clambake:

You don’t need to be a music theorist to hear it. Here they are together: listen to how the first phrase works, and the second phrase (“Faithful friends”) doesn’t (15 sec):

<silent scream>

I know what you’re thinking. I’m a petty little man, and he’s Lou Rawls. But imagine that for years you’ve adored the genius that went into one tiny corner of a beautiful painting, a detail that no one else seems to notice or comment on. Then one day you see someone walk by and squirt their clam sandwich onto that exact spot. I don’t care if it was Michelangelo himself who bit the sandwich, you’re still gonna be pissed.

I love you Mr. Rawls, but dude, napkin.

What Happens When “Happy” Goes Minor?

- November 06, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined

0

0

Major is happy, minor is sad. It’s the one music theory thing that everybody knows. But what happens when you cross the streams, taking a major song and throwing it into the soul-crushing abyss of a minor key?

That’s just what Chase Holfelder’s Major to Minor project does, turning upbeat numbers like “Kiss the Girl” from The Little Mermaid into a creepy assault fantasy, and making the sweet tribute to undying love that is “I Will Always Love You” into a soundtrack of dark obsession (20 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/_xz10ZNNkoM” parameters=”start=113 end=134″ /]

But there’s one pretty obvious target that Chase hasn’t transmogrified yet — a song so happy that its actual name is “Happy.” So I wonder what happens if you take Pharrell Williams’s infectiously danceable hit and put it in a minor key?

I’ll tell you what happens. NOTHING happens — because “Happy” is already in minor.

[arve url=”https://giphy.com/embed/g1a84q6RBSMrS” /]

You don’t believe me OR Anna Kendrick? Fine. First a taste of the original, then I’ll wreck it to prove my point (24 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y6Sxv-sUYtM” parameters=”start=11 end=36″ /]

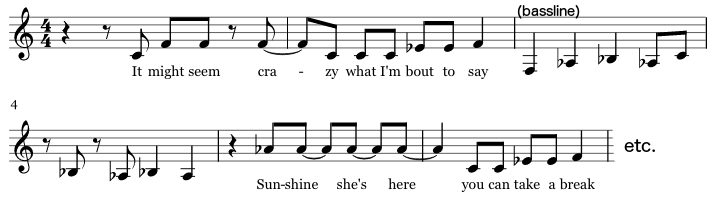

If you read music, you can see it on the page. The F minor scale has Ab, Db, and Eb — F major does not:

Straight up F minor.

Now there is a little major cream in the minor coffee of this song, a few A-naturals peeking through here and there. It’s a common practice in jazz and R&B to let major and minor knock up against each other. But there’s no doubt that minor wears the pants in this one. If I scrubbed every little fleck of major from “Happy,” turning it all minor, you’d hardly notice the difference. Turn it all major, though, and the song is destroyed.

Lemme crank up my quaint Korg M-1 to do a reverse Holfelder, switching “Happy” from minor to major. Here’s the opening:

Gah. It’s like the Partridge Family at its whitest.

Even worse is what happens to this spot, where the backup singers sing “Happy, happy, happy, happy…” (12 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y6Sxv-sUYtM” parameters=”start=121 end=132″ /]

Here it is in F major:

Okay, so “Happy” is minor. But how can that be? How can anything as happy as “Happy” be in a minor key?

The answer is that emotion in music isn’t on a simple major/minor toggle. A lot of variables are in play. In his remixes, Holfelder never only changes the mode to minor — he messes with tempo, instrumentation, dynamics, vocal stylings, and chord structures as well.

This goes both ways: By fiddling with other switches, music in a major key can be just as sad as minor. This devastating number from Les Miz is in a major key:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/86lczf7Bou8″ /]

And aside from sad, a minor key can be powerful, goofy, thrilling…and yes, even happy.

Don’t miss a post! Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

No One Owns the Worst Song in the World

- December 10, 2015

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined

0

0

A U.S. District Court judge recently ruled that Warner/Chappell Music Inc. doesn’t own the song Happy Birthday after all. They’ve been earning $2 million a year in royalties for it, mostly for film and TV use. Remember the Friends episode where the waiters gathered around the table to sing Happy Birthday to Joey even though it was Phoebe’s birthday? That cost the show five grand, easy.

The gravy train is over for Warner/Chappell. The suffering continues for the rest of us. “Happy Birthday” is just about the worst song in the world.

It isn’t just the song itself. There’s also the painful, untextured ritual of it, year after year, party after party, unvaried but for the occasional loveless insertion of cha-cha-cha. It is a bit of mummery that brings joy to exactly no one, ever. It’s a thing we do because it is done. And every time we sing it, 15 seconds drop through the drain at our feet, never to be recovered.

Happy Birthday.

So the bland ritual is bad, but so is the actual song. Start with the words. Imagine what we could say to each other every year! We could have a song that reminds us what a birthday really is:

Once again the earth comes ’round

To where you came to be

And now we celebrate before

You’re snuffed by entropy.

Okay, a work in progress. But “Happy Birthday to you” four times? That’s just phoning it in.

Speaking of which, the first notes of the melody include one of the most boring possible melodic structures:

The note on “Birth” is called a neighbor tone. Start on a note that’s in the chord, go up (or down) one step, then back to the first note again. That’s a neighbor. Now add the fact that this particular one goes up to the sixth note of the major scale, the absolutely least interesting pitch in the scale, and you have the musical equivalent of lifting your head from the pillow for a moment before laying it down again.

After an admittedly cool accented passing tone on the first syllable of the birthday kid’s name — you get a tritone with the bass if harmony is playing, very nice — time begins to stretch:

Happy Birthday Dear Miiiiiiikeeeeeeeey…

We draw the name out in a rallentando, then hang a big caesura (a hold) over the last syllable. Why? We’ve been singing for all of eight seconds, I don’t need to rest. Yes, drawing out their name makes the kid feel special…but tick tick, you know? I say keep the tempo steady, save three seconds each time, and hike Denali with the time you accrue over the years.

Okay, I’ve dissed the Star-Spangled Banner and Happy Birthday. Next time I’ll go after Amazing Grace.

Photo by Omer Wazir | CC 2.0

The (Actual) Evolution of Cool

- October 30, 2015

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined, Unweaving

0

0

Tower of Power was my band in high school. One reason was the insanely tight horn section, including SNL frontman Lenny Pickett. But another was the music itself.

It was cool.

I was also a marching band guy, and I always liked me some Sousa marches, though not for the same reasons I liked Tower. Sousa has horns, and they might be tight, but nobody would call “Stars and Stripes Forever” cool. Strong maybe, proud, confident, celebratory — but cool doesn’t enter into it.

Doesn’t matter if you like a piece of music or not. I hate certain kinds of jazz, for example, while still recognizing that they exist in the wheelhouse of “cool.” And I’ve always wondered what accounts for that instantly recognizable quality.

Now I think I’ve found it.

A few posts ago I mentioned a hideously wrongheaded passage about dissonance from the book This is Your Brain on Music by Daniel Levitin. The rest of the book was entirely rightheaded — and one section in particular blew my mind.

I double-majored in music and physical anthropology, so any time I trip over a credible link between music and evolution, there is much rejoicing. In one chapter, Levitin explores a fascinating function of the cerebellum that crosses that very bridge: timekeeping.

The cerebellum is one of the oldest structures in the brain, so any adaptive features located there are likely to have deep evolutionary advantages. They are likely, in other words, to benefit not only humans, but the common ancestors we share with a whole lot of other creatures.

The cerebellum is mostly about coordinating movement, but researchers have also found it getting busy when we listen to music. Long story short, it seems to correlate to the pleasure (or lack) that we get from the rhythm in a song. As a Salon article a few years back put it,

When a song begins, Levitin says, the cerebellum, which keeps time in the brain, “synchronizes” itself to the beat. Part of the pleasure we find in music is the result of something like a guessing game that the brain then plays with itself as the beat continues. The cerebellum attempts to predict where beats will occur. Music sounds exciting when our brains guess the right beat, but a song becomes really interesting when it violates the expectation in some surprising way — what Levitin calls “a sort of musical joke that we’re all in on.” Music, Levitin writes, “breathes, speeds up, and slows down just as the real world does, and our cerebellum finds pleasure in adjusting itself to stay synchronized.”

That’s great. But why would this ability have evolved? Why does evolution care what music you like?

Honey…evolution doesn’t give a damn about you personally, much less what kind of music makes your weenie wiggle. But on the population and species level, it does tend to favor abilities that keep an organism alive a little longer. One of those is the ability to detect small changes in the environment, because change can indicate danger. Here’s Levitin:

Our visual system, while endowed with a capacity to see millions of colors and to see in the dark when illumination is as dim as one photon in a million, is most sensitive to sudden change….We’ve all had the experience of an insect landing on our neck and we instinctively slap it—our touch system noticed an extremely subtle change in pressure on our skin….But sounds typically trigger the greatest startle reactions. A sudden noise causes us to jump out of our seats, to turn out heads, to duck, or to cover our ears.

The auditory startle is the fastest and arguably the most important of our startle responses. This makes sense: In the world we live in, surrounded by a blanket of atmosphere, the sudden movement of an object—particularly a large one—causes an air disturbance. This movement of air molecules is perceived by us as sound….

Related to the startle reflex, and to the auditory system’s exquisite sensitivity to change, is the habituation circuit. If your refrigerator has a hum, you get so used to it that you no longer notice it—that is habituation. A rat sleeping in his hole in the ground hears a loud noise above. This could be the footstep of a predator, and he should rightly startle. But it could also be the sound of a branch blowing in the wind, hitting the ground above him more or less rhythmically. If, after one or two dozen taps of the branch against the roof of his house, he finds he is in no danger, he should ignore these sounds, realizing that they are no threat. If the intensity or frequency should change, this indicates that environmental conditions have changed and that he should start to notice….Habituation is an important and necessary process to separate the threatening from the nonthreatening. The cerebellum acts as something of a timekeeper.

Our cerebellar timekeeper determines how regular a sound is. If it stays predictable — dripping water, chirping crickets — we feel confident and secure. If it becomes less predictable or changes in intensity, we feel unsettled, possibly threatened.

Listen:

The Thunderer, John Philip Sousa

The beats are regular. Your cerebellum is tapping its foot, predicting every beat, right on the money. It makes you feel safe, confident, in control. It’s a great performance of a great march, but no one would call it cool.

Then there’s this…hold me…

“Sacrificial Dance” from The Rite of Spring, Igor Stravinsky

In addition to intense dissonance, it’s jerky and angular, with completely unpredictable rhythms and sudden changes in intensity — the musical embodiment of anxiety and terror. And it bloody well should be — a sacrificial virgin is dancing herself to death on a fire, for God’s sake. Your cerebellum is freaked out by the utter inability to predict the next note. The music is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do, but you wouldn’t call it cool.

The music we usually identify as cool splits the difference, combining a steady predictable beat with unpredictable departures from that beat. It’s flirting with the remote sense of danger without actually endangering you. Once again, a rollercoaster analogy works perfectly: the feeling of being tossed around without actually getting killed can be thrilling.

If music establishes a beat, then throws you around a bit — backbeat accents, unexpected hits around the beat, changing patterns — it gives a little thrill to your cerebellar timekeeper, tickling that part of you that listens for the irregular sounds of danger, then pulling you back to the safety of a steady beat before dangling you over the cliff again.

Let’s all agree that “Superstition” by Stevie Wonder is cool. Listen to how the drums set a metronome-steady beat for the first 10 seconds. Then that funky clavinet comes in, a mix of on-beat and jerky staccato syncopations. By the time the horns are in, we have layers of offbeat counterpoint dancing around the steady beat, this complicated tapestry of sound:

In the end, the proof is in the ruining. If you want to strip all of the cool out of a cool song, make it safe. Take every unpredictable syncopation and put it on the beat, like every middle school arrangement of every popular song:

Dude. Not cool.

Bonus cool: My favorite song in high school

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

The Case Against the Star-Spangled Banner

- October 13, 2015

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined

0

0

It’s a waltz, for starters. Nobody else has a national anthem that’s a waltz. Okay, there’s “God Save the Queen,” but that’s it. The rest are proper marches or noble hymns, not prancy little dance ditties.

Lemme start over.

Every once in a while, someone in Congress introduces a bill to replace the current US national anthem, usually based on its militarism or unsingability.

The case against the Star-Spangled Banner starts there, but there’s much more wrong with our national song. By the end of this post, I hope you’ll join me in writing your representatives so the bill can be raised and defeated yet again.

Here are nine reasons to be all-done with The Star-Spangled Banner.

1. It’s militaristic.

Well it is. Why sing about rockets and bombs when we could celebrate spacious skies and amber waves? Not that I have any particular replacement in mind.

Granted, the militarism of the SSB pales in comparison to the most bloodthirsty national anthem on Earth, “La Marseillaise” (shudder). While it’s musically magnifique, the French anthem is a festival of rage and gore, including throat-cutting, watering the furrows of the Homeland with the impure blood of enemies, and the children of France yearning to join their ancestors in their coffins.

Ours celebrates surviving an assault, not slaughtering the foe, I’ll give it that. So it’s not as militaristic as La Marseillaise, which is like not being as rude as Stalin.

2. It’s unsingable.

The range is too wide – an octave and a fifth, from middle B-flat (on “say”) to very-high F (on “glare” and “free”). That’s why ballpark wise guys do a falsetto yodel up to double-high B-flat on “land of the freeee” – to give the impression that they really could have held that F without cracking, but they’re just, you know, messin’ around.

3. The War of 1812…Seriously?

Francis Scott Key’s poem “The Star-Spangled Banner” commemorates the siege of Fort McHenry during that most heart-poundingly memorable of our national military conflicts, the War of 1812. Who could ever forget the Chesapeake-Leopard incident, the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the traitorous clamor of the Hartford Convention…

Look, it was an odd war. The British had been boarding our ships looking for deserters, and we asked them to stop. They wouldn’t, so we declared a war that ended three years later in a draw. Not really the stuff of anthems, in my humble. (And the 1812 Overture, by the way, our 4th of July favorite, doesn’t have anything to do with the War of 1812. It was written by a Russian to commemorate the forced retreat of Napoleon from Moscow. But that’s a separate facepalmer.)

4. It’s not militaristic enough.

If you’re going to write about an artillery bombardment, bring it. Instead, right when we’re singing about rockets and bombs, the band goes quiet and shifts to the woodwinds. Here’s the US Marine Band depicting a naval assault (16 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R39e5dOc7AU” parameters=”start=34 end=50″ /]

The music here doesn’t fit the text. This spot is not technically the fault of the song itself, but it’s woven so deep into the arrangement tradition by now that I’ll sustain the objection.

5. “Bombs bursting” can hardly be said, much less sung.

Ever notice that the crisp dotted eighth-sixteenth of the first stanza (O-o say and By the dawn’s) gets ironed out to two eighth notes in the middle of the verse? Sometimes you still get the dotted rhythm for And the rock-, but no one has tried to sing The bombs burst- in a dotted rhythm since the mass lip-mangling incident at Game 3 of the 1937 World Series. You may have noticed that ambulances now attend every sporting event where the National Anthem is sung, just in case someone tries it again.

6. Did I mention it’s a waltz?

Music with beats in groups of two or four can be many things – moving (America the Beautiful); peaceful (Pachelbel’s Canon); stirring (The Marseillaise); sensuous (Girl from Ipanema); or even an electrifying thrill ride (The Macarena). But waltz time just goes oom-pa-pa.

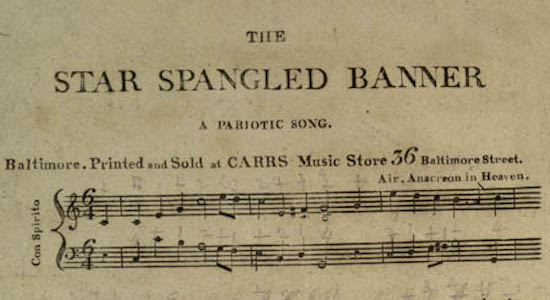

7. The tune is English.

Who were we fighting in 1812? The hated Costa Ricans? The dreaded Laplanders? No, it was the English. So when we dug into our repertoire for a tune that matched the metrical structure of the poem Francis Scott Key had written commemorating our victory over the English, we chose “To Anacreon in Heaven” – an English drinking song.

8. IT’S A DRINKING SONG.

“To Anacreon in Heaven” was written in London in the 1770s by members of the Anacreontic Society, an upper class men’s club that met at the Crown and Anchor Tavern to sing the praises of…well, let’s just see. Here’s the first verse of the lyrics – you know the tune:

To Anacreon, in Heav’n, where he sat in full glee,

A few sons of harmony sent a petition,

That he their inspirer and patron would be,

When this answer arrived from the jolly old Grecian –Voice, fiddle and flute, no longer be mute,

I’ll lend ye my name, and inspire ye to boot…

And, besides, I’ll instruct ye, like me, to entwine,

The myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s vine.

So Anacreon, a Greek lyric poet of the 6th century BCE, approves the use of his name and instructs the “sons of harmony” to “entwine the myrtle of Venus” – the goddess of love – “with Bacchus’s vine” – the god of wine. He tells them, in short, to have drunken sex.

In subsequent verses, Zeus is made furious by the news of the proposed entwining, convinced that the goddesses will abandon Olympus in order to have sex with wasted mortals, and dispatches Apollo to stop it. But Apollo is laid low with diarrhea and, fleeing his citadel with his “nine fusty maids,” is rendered unable to countermand the order.

I couldn’t make this stuff up on my best day.

Yes, the tune had other lives in the intervening years. It was exported to the United States as early as 1798 and reset to various lyrics, including that old toe-tapper “Adams and Liberty.” But don’t you think the original setting kind of, I don’t know – adheres a bit? No matter how much time passes, I don’t expect “I Like Big Butts” to ever give rise to a hymn tune, no matter what other incarnations it has between now and then.

9. It’s not sacred. In fact, we did without a national anthem for over 150 years.

Though Key’s poem “The Star-Spangled Banner” was around from 1814 and even got the tune stuck to it shortly thereafter (as a spritely dance), it wasn’t adopted as the national anthem until 1931. This ancient, venerable tradition was born the same year as my dad. Prior to that it was just another national song, on par with “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and “Hey Nonnie Noo, I’m a Yankee Too!”, which doesn’t even exist. Before that, the United States of America had no official national anthem. Even Estonia beat the pants off us. They got their anthem in 1869 – and not from a barroom floor, I’ll bet.

So why not give an aggressive, unsingable, recently-adopted, ill-constructed waltz-time descendant of a raunchy bar ballad turned celebration of obscure military stalemate the heave-ho?

Because it’s tradition, silly.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/3l-n64NWHS4″ /]