on borrowed memes and missed compliments

You may have seen the article in TIME Magazine about the weekly children’s program at the Humanist Community in Palo Alto, California:

On Sunday mornings, most parents who don’t believe in the Christian God, or any god at all, are probably making brunch or cheering at their kids’ soccer game, or running errands or, with luck, sleeping in. Without religion, there’s no need for church, right?

Maybe. But some nonbelievers are beginning to think they might need something for their children. “When you have kids,” says Julie Willey, a design engineer, “you start to notice that your co-workers or friends have church groups to help teach their kids values and to be able to lean on.” So every week, Willey, who was raised Buddhist and says she has never believed in God, and her husband pack their four kids into their blue minivan and head to the Humanist Community Center in Palo Alto, Calif., for atheist Sunday school.

All in all a positive piece about what seems to be a lovely program by a very strong and positive group of folks. Very few wincers in the article.

It’s unfortunate but predictable that the response in many fundamentalist religious blogs has been jeering and mockery. Albert Mohler (president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) called it an “awkward irony.” Others have claimed that the fact that atheists spend so much time denying God is “proof that God exists,” or found the idea otherwise worthy of contempt.

I’ve looked in vain (so far,anyway — please help me out) for a Christian blog that says what I think is obvious, and what is essentially stated in the article itself: that this represents an enormous compliment from secular humanism to Christianity. Systematic values education for children is something they’ve developed much more successfully than we have. And for good reason: they’ve had a lot more time, centuries of development and refinement. We humanists have always attended to the values education of our kids, of course, but until quite recently it has mostly taken place at the family level. When it comes to values education in the context of our worldview community, Christians have had more practice. In the past generation, such efforts as UU Religious Education, Ethical Culture, and the Humanist Community program have begun closing that gap in the humanist infrastructure.

One of the most marvelous and successful programs in the world is the Humanist Confirmation program in Norway. According to the website of the Norwegian Humanist Association, ten thousand fifteen-year-old Norwegians each spring “go through a course where they discuss life stances and world religions, ethics and human sexuality, human rights and civic duties. At the end of the course the participants receive a diploma at a ceremony including music, poetry and speeches.” They are thereby confirmed not into atheism, but into the humanist values that underlie all aspects of civil society, including religion.

HUMANIST ORDINANDS IN NORWAY,

SPRING 2007

All of these secular efforts at values education can be seen as an evolution of religious practices, opening conversations about values and ethics while working hard to avoid forcing children into a preselected worldview before they are old enough to make their own choice. And though the practices themselves often have religious roots, the values themselves are human and transcend any single expression.

Instead of mocking and jeering, I’d like to see Christians recognize and accept these adaptations as genuine compliments. Perhaps the first step is for humanists to say, clearly, that they are meant as compliments. I can’t speak for the Humanist Community, nor for the Norwegian Humanists, but I can speak for Parenting Beyond Belief. The Preface notes that

Religion has much to offer parents: an established community, a pre-defined set of values, a common lexicon and symbology, rites of passage, a means of engendering wonder, comforting answers to the big questions, and consoling explanations to ease experiences of hardship and loss.

Just as early Christians recognized the power and effectiveness of the Persian savior myths and borrowed them to energize the story of Jesus, there are currently things that Christians do much better than we do. I’m preparing a post on that very topic. We should not be shy about considering their experiments part of the Grand Human Experiment, setting aside the things that don’t work, with a firm NO THANKS, then borrowing those things that work well, and saying THANK YOU — much louder and more sincerely than we have done.

bookin’ through the bible 2

[Back to bookin’ through the bible 1]

Before we begin, let’s select our study materials. You will need:

1. A Bible OR a link to the text online. We’ll be referring to the NRSV.

2. A concise online commentary from the believers’ perspective. I recommend this one.

3. A concise online commentary from the critical perspective. I recommend this one.

4. The brilliant and fun OT commentary David Plotz did for Slate: Blogging through the Bible.

1. Pick a Bible

Naive skeptics and believers alike might think this doesn’t much matter, but it does. Rather than waste word count explaining why, I’ll demonstrate it. When Pilate asked Jesus if he was the Son of God, in Matthew 26:64:

Jesus saith unto him, Thou hast said. (King James version, 1611)

Jesus saith to him, Thou hast said. (Young’s literal translation 1898)

“That is what you say!” Jesus answered. (Contemporary English version, 1995)

Jesus said to him, “You have said so.” (English Standard Version, 2001)

This lawyerly, even Clintonesque non-answer has long been a source of discomfort in Christian circles. Why didn’t he just say YOU’RE DAMN RIGHT I AM! instead of the 1st-century equivalent of I’m rubber, you’re glue? Solution for some denominations? Stick your hand up his robe and MAKE him say what you need him to say. Here’s Matthew 26:64 in three other editions:

Jesus said to him, “What you said is true.” (New Life Version, 1969)

Jesus said to him, “It is as you said.” (New King James, 1982)

Jesus answered him, “Yes, I am.” (Worldwide English version, 1996)

My suggestion, and the suggestion of many others, is to go with King James. It predates the modern revisionist trend and is the most beautiful English translation by a mile. the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

2. The Approach

Keep your approach as unmediated as possible. That said, the insights of others who’ve spent serious time with this book can be very helpful indeed. That said, you want to balance your input between believers and skeptics.

So for our little study time together, I’ll recommend the following:

Read the assigned book for the week (e.g. Genesis) without commentary.

THEN read the Introduction for that chapter from the New International Version (NIV) Study Bible, available online (or the believerly source of your choice).

THEN read the relevant section in the Skeptic’s Annotated Bible, a tremendous online resource that provides the text of the Bible with running marginalia calling attention to the good, the bad, and the ugly.

THEN, for the Old Testament, read the relevant section of David Plotz’ Blogging through the Bible.

I’ll provide these links in each post.

3. The Selections

Yes yes, the best thing to do is to read the entire Bible. There, I said it, and I suppose it’s true, and others are doing that as we speak. Having done it myself, I can assure you that by reading a balanced selection of complete books from the Bible, you can get an excellent idea of what all the fuss, positive and negative, is about.

I’ve selected books in much the way you’d select a grade school basketball team, allowing the Christian and Skeptic captains to choose books alternately. I started by scanning Christian Bible study websites to see which books they are excited about. Unsurprisingly, the four Gospels at the center of things, followed by the Epistles of Paul, followed by Acts and Hebrews.

Skeptics, on the other hand, want you to read the Pentateuch (Genesis through Deuteronomy), followed by Judges, followed by a New Testament mix-and-match.

Here are four ways to slice it:

PLAN A (The Toe-Dip)

Busy as hell? Just read Genesis and Luke. Total commitment: 5 hours.

PLAN B (The Scriptural Sponge-Bath)

For a good scriptural flyover, read Genesis, Exodus, and Leviticus from the OT, and Luke, Acts, and Revelation from the NT. Total commitment: 12 hours.

PLAN C (To the Waist, with Water Wings)

This is our baby. Genesis; 1 Corinthians; Mark, Matthew, Luke, John (the approximate order written); Exodus, Leviticus, Deuteronomy; Ecclesiastes and (just for fun) Song of Songs; Acts; Revelation. Total commitment: 25 hours.

PLAN D (Full Immersion)

The whole megillah. Total commitment: 80-90 hours.

We’ll be following Plan C. I’ll be giving very minimal commentary, mainly pointing you to others who’ve already done that work. Remember that the goal is literacy and clear-eyed knowledge of this influential book, both for ourselves and for our kids. Here’s an approximate blog schedule in 11 installments. These will be interwoven with posts on unrelated topics. Drift in and out as you like:

Dec 3 — Genesis

Dec 10 — 1 Corinthians

Dec 17 — Mark

Dec 24 — Matthew and Luke

Dec 29 — John

Jan 8 — Exodus

Jan 15 — Leviticus

Jan 22 — Deuteronomy

Jan 29 — Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs

Feb 5 — Acts

Feb 12 — Revelation

So start by reading the intro to David Plotz’ Blogging through the Bible — but don’t read his Genesis post yet! — then go y’all forth now and read Genesis! Here are your links:

Book of Genesis online

Believers on Genesis

Skeptics on Genesis

Plotz on Genesis

bookin’ through the bible 1

You’ve got to love the Bible — not for what it reveals about an alleged supreme being, but for what it reveals about us, the monkeys who wrote it and who’ve kept it a bestseller for two millennia and counting.

The fact that this mishmash of exceeding good and outrageous evil, of genuine wisdom and utter nonsense, of sublimity and unintended farce, of perfect love and bottomless hate, continues to resonate for so many people in the 21st century is a function of what it really is: a mirror. We are good, evil, wise, nonsensical, sublime, farcical, loving and hateful. How can you not love a book that shows us so unashamedly for the self-contradictory mess we are?

Here’s a thoughtful take from the good folks at Skeptics Annotated Bible:

For nearly two billion people, the Bible is a holy book containing the revealed word of God. It is the source of their religious beliefs. Yet few of those who believe in the Bible have actually read it.

This must seem strange to those who have never read the Bible. But anyone who has struggled through its repetitious and tiresome trivia, seemingly endless genealogies, pointless stories and laws, knows that the Bible is not an easy book to read. So it is not surprising that those who begin reading at Genesis seldom make it through Leviticus. And the few Bible-believers who survive to the bitter end of Revelation must continually face a disturbing dilemma: their faith tells them they should read the Bible, but by reading the Bible they endanger their faith.

When I was a Christian, I never read the Bible. Not all the way through, anyway. The problem was that I believed the Bible to be the inspired and inerrant word of God, yet the more I read it, the less credible that belief became. I finally decided that to protect my faith in the Bible, I’d better quit trying to read it.

The most popular solution to this problem is to leave the Bible reading to the clergy. The clergy then quote from the Bible in their writings and sermons, and explain its meaning to the others. Extreme care is taken, of course, to quote from the parts of the Bible that display the best side of God and to ignore those that don’t. That this approach means that only a fraction of the Bible is ever referenced is not a great problem. Because although the Bible is not a very good book, it is a very long one.

But if so little of the Bible is actually used, then why isn’t the rest deleted? Why aren’t the repetitious passages — which are often contradictory as well — combined into single, consistent ones? Why aren’t the hundreds of cruelties and absurdities eliminated? Why aren’t the bad parts of the “Good Book” removed?

Such an approach would result in a much better, but much smaller book. To make it a truly good book, though, would require massive surgery, and little would remain. For nearly all passages in the Bible are objectionable in one way or another.

Perhaps. But to the Bible-believer…each passage contains a message from God that must not be altered or deleted. So the believer is simply stuck with the Bible.

Jefferson made one such attempt at corrective surgery with the New Testament.

Whether you’re a believer or a nonbeliever, to get a real grasp of this strange and influential book, at some point you’ll have to go straight to it. Spoonfeeding and cherry-picking add up to religious illiteracy. And with religion dominating and influencing everything from individual actions to world events, religious illiteracy is something we can no longer afford. That includes secular parents. UU Rev. Bobbie Nelson hit the nail on the head in Parenting Beyond Belief:

Choosing not to affiliate or join a religious community does not shield a parent from [religious] questions–you will still need to be able to answer some or all of them. If you do not provide the answers, someone else will–and you may be distressed by the answers they provide.

If that sent a chill down your parental spine, and your exposure to the Bible has so far been secondhand, it’s time to get up close and personal with this long-resonating collection of goat-herd lore.

But like SAB said above, there’s nothing like picking up a Bible to make you want to put it down again. The Bible is protected from close examination by the very idea of plowing through 770,000 words in six-point font (including no fewer than 10,941 shalls). While the daunting size and tedium of the bible serves the needs of the church, which giddily stands in the explanatory breach, it also prevents understanding on all sides. It prevents secularists from engaging the exquisite poetry of Ecclesiastes and Luke (etc) and the faithful from recognizing the genuine poison of Deuteronomy and Revelation (etc etc).

But 770,000 words of Bible prose is roughly 80 hours. I wouldn’t ask you to do that — there are too many books both good and influential to spend that much time on one that’s merely influential. Fortunately you don’t need to read the whole thing to greatly enhance your Biblical Quotient. Crack the cover and you’ve already passed up as much as 72 percent of Christendom.

We here at Meming of Life International have designed a multi-tiered bible reading plan for the secularist. Whatever your level of commitment, from toe-dipping dilettante to full immersion dilettante, we’ve got a plan to match your lifestyle.

Unfortunately, I’ve set a new goal: an absolute 1000-word limit per post, about six minutes of reading, and we’re just about there for today. In the coming weeks I’ll include a few more posts outlining our patented Bible Study Plan for Non-Goatherds™. So get yourself a Good Book…so you have something to read when you’re done with the Bible.

“why does she always have to be ‘so beautiful’?!”

- October 24, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In diversity, My kids, myths, Parenting, values

17

17

HELEN OF TROY, looking (as usual) decidedly un-Greek

I like what’s happening to my nine-year-old middleborn, Erin B. And I don’t like what’s happening to me.

First of all: I know I’ve blogged a lot recently about bedtime myths and legends, and I don’t want to give the impression that my kids are on some force-fed diet of classic western civ. Every night I give them a choice of whatever they want to read. And for the last several weeks, the girls always yell, “Myth! Myth!” (To which I can only respond, “Yeth?”)

Last week it was Sir Gawain and the Green Knight — one of my favorite Arthurian legends, despite some admittedly strange bits. One reason I like it: I have a hunch that Gawain derives from Gowan, which is Gaelic for “blacksmith” and the root of our family name. Anyhoo, Gawain arrives in the Forest of Wirral, only days before his scheduled re-encounter with the Green Knight. Tired, he spots a nice castle and makes for it. The lord of the castle takes him in and gives him a great meal. Ahem:

After the meal was finished, the lord of the castle brought Gawain into a sitting room and sat him in a chair by a roaring fire. At last, the lady of the castle came to visit them. She was so very beautiful that she outshone even Queen Guinevere…

“Why does she always have to be ‘so beautiful’?!”

I blinked. It was Erin, her face scrunched into a frown. “Well…she doesn’t have to be, B. She just is.”

“But they always are! ALL the ladies in the myths are (in a mocking voice) ‘so beautiful’! Every one!”

Huh?? “They aren’t always…” My voice trailed off a bit in the manner of someone who realizes, too late, that he’s talking through his hat. Clearly she had noticed something I had not.

“Yes! They are! What about the one last night?” The night before we read Pyramus and Thisbe, the deep precursor to Romeo and Juliet. I reached up and pulled our condensed Age of Fable off the shelf and thumbed to the story.

First sentence:

Pyramus was the handsomest youth, and Thisbe the fairest maiden, in all Babylonia.

Hm. “Okay, so two in a row. But…”

“And Psyche!”

Hm. I flipped to Cupid and Psyche:

A certain king and queen had three daughters. Two were very common, but the beauty of the youngest was so wonderful that mere words…

Psyche Entering Cupid’s Garden

John William Waterhouse (c. 1904)

Huh. I began to search my mind, desperately, for a myth I had recently trotted before my girls in which a woman’s intelligence was praised, or her strength — something beyond her looks.

“Aha!” I said at last. “What about Atalanta? She was smart and faster than all the men!” I flipped to the page. “And her beauty wasn’t part of the story. Here: ‘Atalanta was a maiden whose face was boyish for a girl, yet too girlish for a boy.’ See?”

“Keep reading,” she said. “I remember.”

Sure enough, in the next paragraph, Atalanta, in a footrace, “darted forward, and as she ran, she looked more beautiful than ever.”

______________________

“I began to search my mind, desperately,

for a myth I had recently trotted before my girls

in which a woman’s intelligence was praised, or her strength —

something beyond her looks.”

______________________

No use going back one more night, I knew. That was the night we read about the Trojan War — starring Helen of Troy, “the most beautiful woman in all the known world.”

Holy crap!

I was about to bring up Medusa, but she’s the exception that proves the rule. According to Ovid, she was once beautiful, until she seduced Poseidon, and jealous Athena turned her into a hideous snake-haired beast. Again, looks are at the center of things.

One of the most interesting things about Erin’s exasperation is that (even by the testimony of non-parentals) she is a beautiful girl. Yet she can see that reducing a person to a single surface attribute is insulting, limiting, even when she herself has that attribute in spades. When she was not even three years old, we did a great little routine for friends and family. I’d say “Erin is beautiful and smart,” to which she would reply, without missing a beat, “An unnnnbeatable combo!”

I was proud of her for recognizing the anti-feminist vein in the old stories–and ashamed of myself for going numb to it. Why did I need my nine-year-old to remind me? There was a time when objectifying references to women made me howl. Fifteen years teaching at a women’s college will do that for you. Sure, I went to Berkeley, but it took a Catholic women’s college (yes, the irony drips) to thoroughly wake me up, to make me a feminist. I know that if I’m not outraged, I’m not paying attention. I know that.

Three days ago, I did it again. Erin walked into the kitchen wearing a fantastic American Indian costume Becca had just whipped up for Hallowe’en. So what did NeanderDad say?

“Erin, look at you! Are you gonna be an Indian princess?”

“No!” she said hotly.

“Uh…Indian maiden?”

“No!!”

“Uh…uh…a squaw?”

That’s right: I said SQUAW! I said SQUAW! Holy crap!

“DADDY!!!”

“Uh…you’re a…you’re a warrior!”

“THANK you!”

Okay. The nonviolence advocate in me winced, but the feminist in me stood tall. Almost as tall as my nine-year-old daughter.

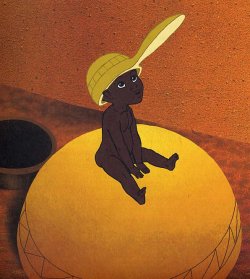

KID MOVIE REVIEW: Kirikou and the Sorceress

- October 15, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, myths, Parenting, reviews

9

9

A movie review for you this time — and oh my goodness, it’s hard to know where to start.

Desperate for something new for the kids, I happened on a film called Kirikou and the Sorceress in my Netflix recommendations. It had all the earmarks of a well-meaning flop, an animated parable based on African folktales — the kind of thing two Berkeley-educated bleeding-heart parents would make their kids sit through while eating Fair Trade seaweed crackers. But the viewer reviews were through the roof, so I took a shot.

And a flop, well-meaning or otherwise, it is not! Within three minutes we were all captivated by this surprising, funny, and uniquely moving animated film. A little boy walks out of the womb of his Senegalese mother, talking up a storm, and learns that the village into which he’s been born is under the thumb of the evil sorceress Karaba. His uncles have been eaten by the witch, and she has dried up the spring from which the villagers get their water.

[SPOILERS FOLLOW.]

His first question: Why is she so mean and evil? The adults are flummoxed by the very question: Does there have to be a reason?

As the adults alternately fight, cheat, and acquiesce to Karaba, Kirikou instead puts himself to the task of undoing the harm she’s done and of figuring her out. In the process, he learns that Karaba is the African equivalent of the man-behind-the-curtain — that most (not all) of her special effects have naturalistic explanations. She didn’t eat the men, for example, and a hidden animal is drinking up the water. He also learns that she is motivated by literal pain — a thorn — no, not in her paw, but in her spine.

The story also contains further evidence that the Christ story is only one version of a universal archetype, as little Kirikou sacrifices his own life to save the villagers — even those who rejected him — then is “resurrected.” And there is much rejoicing.

Also nice are the ways in which this hero paradigm does not parallel the classic western paragon. He is completely unpretentious, makes mistakes and cheerfully corrects them, changes his mind, and at one point, fatigued from his heroics, curls up in his grandfather’s lap for a rest.

Trust me on this one. 74 minutes. Ages 4-12.

[Pathetic sidenote:

The film’s content of natural nudity enraged some overseas distributors. Some requested airbrushing pants on the fully naked boys and men, as well as bras for the topless women. Michel Ocelot refused; this was African culture, and he wanted to stay faithful to it. In some countries, because of the distribution fights, it wasn’t released commercially until four years later.” (Wikipedia)

Allow me a moment to guess in which country most of this outrage was concentrated.]

Official website, including trailer

Netflix page

La version originale est en français!

What if she comes anyway?

Her name was first spoken in hushed tones among children all over America [over] twenty years ago. Even in Sweden folklorists reported Bloody Mary’s fame. Children of all races and classes told of the hideous demon conjured by chanting her name before a mirror in a pitch-dark room. And when she crashes through the glass, she mutilates children before killing them. Bloody Mary is depicted in Miami kids’ drawings with a red rosary that, the secret stories say, she uses as a weapon, striking children across the face.

from “Myths Over Miami” by Lynda Edwards in the Miami New Times, Sept. 1997

“Dad?”

“Yeah, B?” It was Erin, my nine-year-old, nicknamed “The B.”

“Can you come into the bathroom with me?”

“Why, you need to talk about something?” Our family has an odd habit: one person sits on the edge of the tub and chats up the person on the commode. A gift from my wife’s side.

“No…I’m scared to go in there.”

“It’s the middle of the day, B.”

“I know, but…Daddy, just come in with me.”

“Not ’til you tell me what you’re afraid of.”

She hesitated — then said, “The mirror.”

“What about the mirror?”

She leaned in and whispered, “Bloody Mary.”

I resisted the urge to say, No thanks, I’ll have a Tanqueray and tonic. I knew just what she meant. I was a kid too, you know.

“Desirée at school says if you turn off the lights and turn around three times in front of the mirror with your eyes closed and say Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary, then open your eyes — a woman all covered in blood will be looking at you from in the mirror!”

A quiver-chill went through me. I was a kid again. I remember exactly how it felt to hear such ghastly things whispered by a true believer. Their wide-eyed conviction always did a fine job of convincing me as well. But in my day, Bloody Mary came crashing through the glass at you — a detail Erin didn’t seem to need to hear.

“So just go in, leave the light on, and don’t spin around or say the name, B.” I knew how hopelessly lame a thing that was to say. What if she comes anyway? Once the concept is in your head, why, the very thought of Bloody Mary might conjure her up. She might appear just because she knows I know! And she knows I know she knows I know!

“Okay, I’ll go with you. But you know what I’m gonna do.”

“NO DADDY!”

We went eye to eye. “Sweetie, tell me the truth. Do you think Bloody Mary is real, or just a story?”

She looked away. “Just a story.”

“So why be afraid of a story?” Again, I know. Lame! Yes, it’s true, it’s just a story — but ultimately, in our human hearts and reptile brains, such a defense against fear is hopelessly lame.

Her forehead puckered into a plead. “But Daddy, even if she’s just a story — what if she comes anyway?”

See? I remember.

I walked into the bathroom myself and pulled the curtains. She followed, timidly, cupping her hand by her eyes to avoid the vanity mirror. “You don’t have to come in if you don’t want to, B,” I said. She sat on the lid of the toilet, whimpering. I turned out the lights. Nooooohohohoho, she began to moan, with a bit of fourth-grade melodrama.

I walked to the mirror and began to turn. Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary! I opened my eyes. “See?” I knocked on the mirror. “Helloooooo! Hey lady! Look B, nobody’s home!”

Erin peeled her hands from her eyes and squealed with delight. “I’m gonna do it!”

She walked slowly to the mirror, trembling with anticipation. Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary…Bloody Mary! She peeked through her fingers.

“Eeeeeheeheeheehee!” she squealed delightedly, jumped up and down, hugged me. But if you believe she was cured — if you think Daddy’s words were really enough to slay the dragon — then you were never a kid. Maybe we said her name too fast, you see, or too slow, or or or maybe we didn’t believe in her enough. Maybe she just can’t be tricked by skeptical dads into showing herself. Erin didn’t say any of these things, but I know she was thinking them. And sure enough, the very next day, Erin was requiring bodyguards in the bathroom again.

I haven’t tried to talk her out of it. To paraphrase Swift, you can’t reason someone out of something they weren’t reasoned into in the first place. For a while, it’s even a little bit fun to believe such a thing is possible. And thinking I could talk her out of it anyway would be denying an inescapable fact: that when I pulled my own hands from my eyes in that darkened bathroom and saw the mirror, the rationalist dropped back and hid behind me, just for a tiny fraction of a second, as my little boy heart raced at the question that never quite completely goes away:

What if she comes anyway?

[For one of the most hair-raising and powerful essays I’ve ever read, see the full text of Lynda Edwards’ gripping 1997 piece on the Bloody Mary story as told among the homeless children of Miami — complete with illustrations.]

outfoxing the buddha

THE LEGEND OF THE THREE WATERFALLS

1,000 years ago, on a moonlit night, a priest dreamed that Buddha told him where to find three springs with magical powers. This gave the priest much happiness.

Later, when the sun was shining, Buddha turned these springs into three wonderful waterfalls surrounded by trees. Each waterfall confers a different blessing on one who drinks of its waters. One confers health, another wisdom, and the third, love. But no one knows which waterfall brings which blessing.

If you are greedy and drink from all three, you will receive no blessing at all.

* * *

“So,” I asked Connor, my twelve-year old. “Suppose you want one of these blessings really bad. Let’s say health. What do you do?”

He smiled — he loves puzzles — and sank down into himself for a full minute.

At last he emerged. “Okay, I’ve got it.”

“Hit me.”

“Bring a friend who is sick. Have him drink from two of the waterfalls.” He flashed his braces at me. “If he gets healthy, drink from the same two waterfalls. If he doesn’t, drink from the other one.”

Clever boy!

Connor in Upper Brailes, Oxfordshire, UK

October 2004

Ariadne’s threads

I was seeing my girls off to sleep Sunday night when suddenly, without warning, the Bronze Age broke loose.

It was one of those breath-holding parenting moments when you can’t believe your luck at being there to capture it. Delaney (5) announced that she had made up a myth of her own. For some reason I had the presence of mind to grab my laptop and transcribe as she spoke. Read it, then we’ll chat:

The Wall of Parvati

There was a girl named Medusa. And she knew this wall, a big wall, and she hated it. So one day, she sailed off in a boat with her sharpest sword and she went to that wall. When she got there, she took out her sword and destroyed the whole wall.

The god Parvati was watching her, the god of destroying, because it was her wall. So when Medusa left the wall, Parvati made the wall grow back up. When Medusa found out that it grew back up, she sailed off in her boat again, and when she got there, she cut the wall down again.

Parvati saw this happen (she’s an Egyptian), and when Medusa was gone again, she sent two of her Egyptian gods down to that wall and they made the wall grow again.

When Medusa heard about that, she didn’t want to come out in her boat again, so she put out one of her fastest snakes and made it slither to the wall. The snake used its very sharp tail to whip down the wall. But he couldn’t because the two gods were still there. He whipped the gods with his tail, and the poison went straight into them and they fell asleep, and then the snake whipped his tail against every piece of that wall and slithered back to Medusa.

Before I yak this to death, let me repaste her myth with elements cross-referenced to the myths Laney has heard as bedtime stories in recent weeks:

The Wall of Parvati1

There was a girl named Medusa.2 And she knew this wall, a big wall,3 and she hated it. So one day, she sailed off in a boat4 with her sharpest sword5 and she went to that wall. When she got there, she took out her sword and destroyed the whole wall.

The god Parvati was watching her, the god of destroying,6 because it was her wall. So when Medusa left the wall, Parvati made the wall grow back up. When Medusa found out that it grew back up, she sailed off in her boat again, and when she got there, she cut the wall down again.

Parvati saw this happen (she’s an Egyptian),7 and when Medusa was gone again, she sent two of her Egyptian gods8 down to that wall and they made the wall grow again.

When Medusa heard about that, she didn’t want to come out in her boat again, so she put out one of her fastest snakes9 and made it slither to the wall. The snake used its very sharp tail to whip down the wall. But he couldn’t because the two gods were still there. He whipped the gods with his tail, and the poison went straight into them and they fell asleep,10 and then the snake whipped his tail against every piece of that wall and slithered back to Medusa.

1 She knows Parvati from Ganapati Circles the World (Hindu). Parvati is the consort of Shiva and mother of Ganapati (aka Ganesha or Ganesh). Parvati’s also a Gryffindor, of course.

2 From Perseus and Medusa (Greek).

3 The Iliad (Greek). Much is made of the hated wall around Troy in this excellent retelling for grades 2-4.

4 Several of our recent myths included sailing quests — The Golden Fleece, The Iliad, The Odyssey (Greek).

5 Perseus killed Medusa with the infinitely sharp adamantine sword of Hermes (Greek).

6 Shiva’s pro-wrestling name is “The Destroyer.”

7 No idea. We haven’t done any Egyptian myths yet. The Disney flick Prince of Egypt, maybe?

8 This has been a theme in several of the myths we’ve read lately — the sending of surrogates on tasks — including Cupid and Psyche (Greek) and Proserpine and Pluto (Roman).

9 We’ve encountered two magical snakes recently: in the Garden of Eden (Judaic) and in the Sioux myth of the three transformed brothers. And Medusa has snakes for hair, of course, so maybe she plucked one out and sent it on a mission.

10 A jealous Venus tricked Psyche into inhaling a sleeping draught (Roman).

In that context, maybe you can see why I was all agog. My five-year-old daughter had constructed a syncretic midrash.

Midrash is a process by which new interpretations are laid on old legends or scriptures, and/or new stories are synthesized out of elements of older ones, usually for the purpose of instruction. Though early Jews freaked about syncretism across party lines–don’t make me link to the golden calf!–the construction of fictional midrash from within Judaic sources is recognized as a vital part of Jewish teaching.

In The Jesus Puzzle, Earl Doherty argues, with brilliantly grounded scholarship, that the gospel of Mark was just such a midrash, and that “Mark” did not mean it to be taken as literal fact any more than Delaney did. It was a teaching fiction.

But Laney’s work more closely resembles a deeper kind of mythmaking, one common in the Mediterranean Bronze Age and beyond: the syncretic merging of elements from different belief systems into something new and useful. There is much to suggest that the later character of Jesus is such a syncretic construct, sharing as he does the heroic attributes and biographical details of such earlier mythic figures as Mithras (born on Dec 25, mother a virgin, father the sky-god, 12 disciples, entombed in rock, rose on third day, etc), Krishna, Osiris, Tammuz, and countless others.

A fascinating tangent, believe you me, but I’ll never find my way out if I start with that.

So ancient Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cultures spun new tapestries from the threads of religions all around them. Now here’s a 21st century kindergartener doing the same thing. Makes you think we’re onto something fundamentally human.

If we’d exposed Delaney to just one culture, one religion, she could be forgiven for imagining a no-kidding god on the other end of that one dazzling thread. By instead following a hundred threads, she realizes there are just lots of people on the other end — just plain folks, like Delaney — each of them spinning something lovely and new from the old threads they picked up. Follow enough of those threads and you find yourself outside the labyrinth of religious belief entirely, blinking in the sun.

The thing that left me most awestruck is that she even thought of mythmaking as a thing she could do. Picture a Sunday School kid making up his own bible story. Even though that’s just how Matthew and Luke were elaborated out of Mark, once the 4th century bishops weighed in and made it “gospel,” further creative energies have been (shall we say) discouraged. With rare exceptions, we are now receivers of that written tradition, not co-creators. That’s why the experience of hearing Delaney spin her tale moved me so deeply. She recognizes other human hands in the spinning of the mythic tapestry — so why not add her own?