Yes, ‘Stairway’ Was Stolen…Just Like Everything Else

- June 26, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

A jury decided that Led Zeppelin did not steal the iconic opening measures of “Stairway to Heaven” from a passage in the song “Taurus” by the band Spirit. Some people think Zeppelin got away with murder, arguing, “Well just listen to it, jeez!”

In fact, they got away with composing.

Whole-cloth ripoffs like “U Can’t Touch This” aside, the idea that it’s wrong to use a string of notes someone else once used in a similar way stems from a modern misunderstanding of how music is created — the unhelpful romantic myth that every new piece of music is a unique snowflake crafted from the purrs of unborn kittens in the soul of the composer.

In fact, nearly every piece of music you love is made up of 99.9 to 100% recycled materials. That’s not an accident: Composers return again and again to the shapes and patterns in our established musical lexicon because that’s what composing is.

Yes, there are exceptions — mostly radically avant garde pieces that try to make a virtue out of keeping you perpetually balanced on the back legs of your chair. That approach leaves a pretty narrow range of emotional states to explore, things like anxiety and puppy-slapping irritation. Once you’ve rejected all shared musical language, you can mostly forget slowly unfolding emotional experience.

To see what I mean, and why the Stairway lawsuit (and Blurred Lines, and Creep, and yes, even My Sweet Lord) was dumb, let’s take a peek into the workshop.

A Big, Finite List

Most Western music derives from a finite number of raw materials. It’s a big number, but still finite. You have 12 pitches arranged into two main scale types (major and minor), with occasional side trips into five others.

Western harmony is based on triads — three notes stacked in thirds. There are four kinds: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. You can also keep stacking thirds, adding a 7th, a 9th, or an 11th to the triad, and so on.

When a pitch sounds that isn’t in the chord of the moment, it’s a nonharmonic tone, of which there are about 12 types — passing, neighbor, suspension, anticipation, and so on.

Pitches arrange themselves over time in meter and rhythm. Each beat can be divided up into smaller bits, usually in 2, 3, or 4 parts, sometimes something stranger like 5. The most common meters are recurring bundles of 2, 3, or 4 beats called measures, sometimes 6, less often 5, 7, 9, or even 33 beats per measure.

Measures are usually in groups of 4 called phrases. Though it’s rare to have a piece based entirely on three- or five-bar phrase lengths, one of the best emotional devices in music is an occasional abbreviated or extended phrase. Nicely messes with your expectations.

The tonic chord usually goes to V or IV, sometimes to iii or vi, less often ii or vii. Mixing the usual with the unusual is the crux of the game.

Different genres of music have certain core instrumentations. A rock band usually has a guitar or two, bass, drums, and vocals. Sometimes a keyboard. Sometimes horns. Sometimes a flute or banjo. Orchestra has ABC, funk band has DEF, polka band has XYZ. So within a certain genre, the choices are even more constrained, and the similarities between pieces multiply.

On it goes, a large but finite set of variables in pitch, meter, rhythm, instruments. The amazing thing is that such an incredible variety of genres and songs has come out of this large but finite set.

Within the choices available are patterns and combinations that produce certain emotional effects — tension, calm, dread, humor, gravity, power, violence, aspiration, momentum, flight. The existing set of musical elements is drawn on over and over by composers to produce these effects in the same way a million writers dip their buckets into the shared well of language, drawing out existing words and phrases and allusions to produce the effects they need.

When writers need to evoke “bittersweet yearning,” they don’t start cobbling together letters into new combinations to see what might feel both bittersweet and yearny. They draw on the large but finite set of words and phrases that have already been used to capture that feeling.

Music works the same way. You want bittersweet yearning? Try a I-iii progression. It’s been done a thousand times, but that doesn’t mean I can’t do it again, a little differently, and create something that is new but (here’s the point) not unique.

The idea that each piece of music arrives fresh from the sea foam like Aphrodite on the clamshell, and that it must evoke no other existing song, is both detached from reality and paralyzing to the songwriter. When I studied composition, I can’t tell you how many times I sat down at the piano to come up with the germ of an idea, plunked out three notes, and said, Nope…Stravinsky. Three more notes: Nope…Bartok. Frustrated silence: Nope…Cage.

It’s a weird modern conceit. Bach did not tinkle out a phrase and mutter, Nee… Buxtehude. Nee…Couperin. Sheiße! Nor did he write music that had already been written. He used and adapted patterns and combinations that almost always had been used before. You use them in new ways, extend them, evolve them — but you don’t set out to utterly avoid every resemblance to what already exists. The whole idea is bizarre. It seems like it’s encouraging originality, but it’s actually deeply anti-creative.

The Case of Stairway v. Taurus

Stairway to Heaven is exactly as “stolen” as everything else you’ve ever heard. When he sat down to write the song, Page drew on existing materials and norms to create something new. Randy California did the same when he wrote Taurus. In the process, they crossed into similar territory for a few bars.

Both started with the commonest clay: 4/4 meter, the key of A minor, and an acoustic guitar outlining the chords in straight eighth notes and four-measure phrases — each choice so common as to be essentially the default.

Then they both chose a device that’s rich and evocative, and not original to either of them: a descending chromatic bass line (going down by half steps). It’s a device so well established that it has a name — the “lament bass” — and variations of it pop up in everything from Bach’s “Crucifixus” to the Beatles’s “Michelle” to “Chim Chim Cher-ee.” Follow that bass line (13 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG6O4N3wxf8″ parameters=”start=7 end=20″ /]

So the descending chromatic bass isn’t default, but it’s a well known device. The question as always is what you do with it. The composer of “Taurus” did this (28 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xd8AVbwB_6E” parameters=”start=44 end=72″ /]

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

Here’s what Page did with the same bass line (27 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9ioyEvdggk” parameters=”end=26″ /]

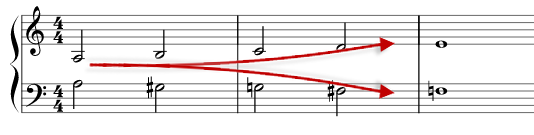

That’s greatness. In addition to the descending bass, Page laid an ascending scale into the upper line (circled notes). Sometimes a pitch is displaced by an octave or off the beat, but your ear hears the ascending line. This creates a wedge that slowly opens — unison, third, fourth, sixth, and finally that delicious major seventh — before returning to the unison/octave:

I’ve pulled out the lines so you can hear them better:

The result is a nuanced, haunting passage written by an artist who knew what he was doing. And this doesn’t even crack open the inspired work in the next hundred measures. I might come back to that.

So: was Stairway directly inspired by Taurus? Who knows. In a better world, Page could stand up and say, “That’s right, I got the idea straight from Taurus. Then I made it better. That’s how this bloody thing works.” And composers would stop suing other composers for composing.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Full songs: Spirit, Taurus; Led Zeppelin, Stairway to Heaven

Jimmy Page image by Dina Regine via Flickr | CC 2.0

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!