Scales! Wait. Come back.

I hated scales in middle school. Oh I was good at scales, even got a certificate for playing all four forms of every scale by memory on my wee clarinet. I was a good boy.

And still I hated them.

It just seemed like such a pointless, hoop-jumping thing to me. Memorize these note patterns, then play each one starting from every possible note, and you win. But aside from the value of rote memorization and the fingering practice…what was the point?

There were other unanswered questions in my head — like Why are there three different kinds of minor scales? Why is the melodic minor different going up and going down? Why does the harmonic minor make me sound like a snake charmer? Why does minor sound sad and major sound happy? Are these the only four ways to get from C to C?

It’s like the Steven Wright joke

Why is the alphabet in that order? Is it because of that song?

Scales are actually cool and interesting once you know what they’re for. Stick with me to the end of the post, then tell me if I’m wrong. (Spoiler: I’m not.)

Last time I split the octave into 12 equal parts to make the chromatic scale. The name hints at the purpose. By containing all 12 of the pitches we use in Western music, the chromatic scale is like a paint store with 12 available colors.

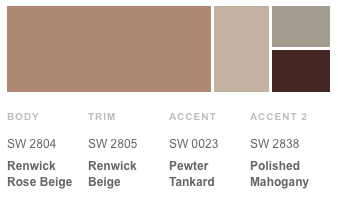

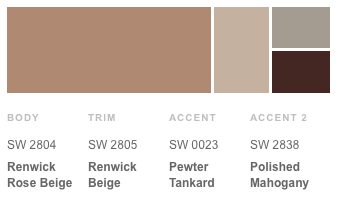

You don’t want every available color for a painting project. You choose a palette — a subset of colors, a theme. If you want this result:

…don’t use every color in the store. Use this palette:

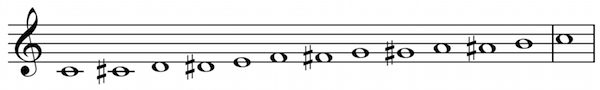

Same for music. The chromatic scale has every available pitch in the Western tonal system. The distance from one to the next is a half step. Here are the 12 half steps of the chromatic scale (plus the next C):

When I write a piece, I don’t need every note. If I want a certain mood, I’ll choose a subset of pitches from the 12 available, and a different subset gets me a different mood.

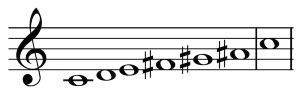

Example: If I choose every other pitch, instead of 12 notes a half step apart, I’ll have 6 notes a whole step apart. That’s called a whole tone scale:

There’s something strange about that scale, right? It starts going off the rails at the 4th note and never gets normal again. Here’s why: All of the pitches are the same distance apart. No half steps. Because of that, your ear can’t easily track where you are. Aside from whatever note we happen to start on, none of the pitches stands out as “home,” so the whole tone scale creates music with an ethereal, directionless quality. If you were a child of the 70s, you know it well. Whenever there was a campy flashback in The Brady Bunch, or Scooby Doo was being hypnotized, there’s a good chance a harp or bells were playing music drawn from a whole tone scale:

One particular Debussy piano piece called Voiles (Sails) is the go-to for illustrating a whole tone scale. Feel that unanchored, homeless quality (0:47):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95_OvaRHwDg” parameters=”start=9 end=56″ /]

The fact that pretty much every theory teacher uses sitcom flashbacks and one Debussy piece as whole tone examples shows you just how rare it is. Beyond drifty sails and coming unstuck in time, a scale with all the pitches equally spaced just isn’t all that useful. If someone gave you driving directions like this — Go one block and left, one block and right, one block and right, one block and left, one block and right, and on and on across town, you’d have a helluva time finding your way home again. Every step is the same. It’s confusing.

If instead the directions were Go one block and left, three blocks and right, one block and left, then five blocks and you’re there — now the steps are different enough to landmark in your head. You need a scale that works the same way — a mix of steps of different sizes so your ear knows where you are relative to home.

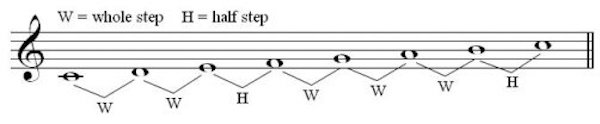

Major and minor scales do just that, creating a pattern of pitches that are different distances apart. They do it by choosing only 7 of the 12 notes, leaving gaps where the other pitches were. The scale shows the ladder of steps between the notes if you arrange them in order. Here’s a C major scale:

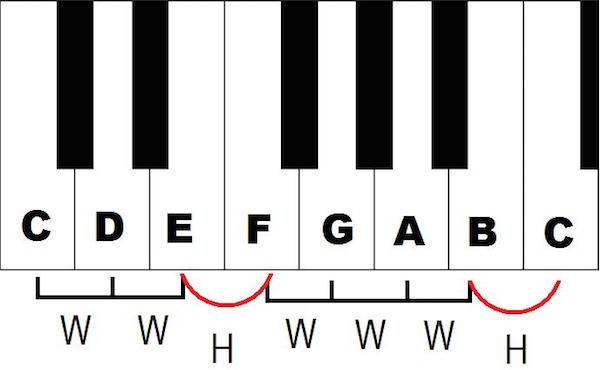

You start on C but leave out C# and go to D — a whole step. It’s like going from red to orange and skipping reddish-orange. The major scale then goes another whole step (to E), then a half step (F), then three more whole steps (G-A-B), and finally a half step to the next C. If you start on C, the white keys on a piano fall naturally into the major scale without any adjustments. The black keys are the gaps, the five chromatic pitches that were left out of the major scale:

If you start on a note other than C, you’ll have to raise or lower notes along the way, using flats and sharps on the page and black keys on the piano to get the same pattern of whole steps and half steps.

Scales aren’t meant to be played in that order any more than the letters in a word are supposed to be spelled out in alphabetical order, or a set of colors in your paint theme is supposed to be painted left to right on the wall by wavelength. Hey, rainbows are great, but you don’t want a rainbow every time you paint. So when you paint your house, this is the scale:

…and this is the music:

The scale is a set of instructions to pick out the colors (pitches) that establish a certain palette (key) for the music you want to write.

But music goes beyond the visual analogy to something that makes its emotional power possible. This pattern also creates a kind of aural map. The sequence of half and whole steps sticks a pin in one of the notes, calling it home, then creates a series of landmarks to tell you where you are relative to that home at all times. By listening to music all your life, your ear has learned how to follow that map — to go away from home, have adventures, and return (or not). The next three JET posts will get into that.

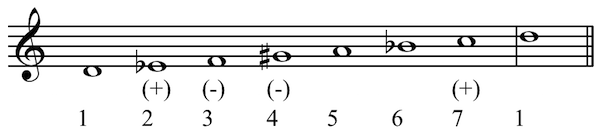

The minor scale is a different pattern of whole steps and half steps spanning the octave. The result is a different emotional palette:

The minor scale results when you lower the third, sixth, and seventh pitches of the major. That’s worth remembering. No need to memorizing key signatures or build scales yourself, but we’ll certainly talk about the various shenanigans the third, sixth, and seventh notes of the scale get up to.

Three great scales from elsewhere

Step outside of Western music and you can really start to see how different scales color the music. I hinted at that last time with the Carnatic microtonal scales. (Don’t be skipping stuff, or all is lost.) Here are three more.

Arabic music has at least 90 different scales, or maqam, each of which provides a different mood. Here’s one, maqam nawa athar:

Which sounds like this:

Hear that? It’s just crammed with intervals that sound exotic to Western ears. If a major scale is a map across your hometown, this one is a map to the market in Marrakech.

Several of the pitches of the Indonesian pelog scale fall in the gaps between our notes, which further shows that all scale divisions are arbitrary and cultural. You can’t even notate pelog properly with Western notation. If you try, you end up with these apologetic little plus and minus signs to indicate “a little higher” or “a little lower” than the notation:

And why not? Remember the sixth overtone, the B-extra-flat? To Western listeners, these pitches sound out of tune because they don’t match our particular divisions, but they have no less claim. Here’s pelog:

And here’s a phenomenal Balinese gamelan playing music using a variant of pelog. If you haven’t heard Balinese gamelan before, strap in, this is awesome:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ldPMifPbngc” /]

Want to evoke a Middle Eastern vibe? Use the Byzantine scale:

It starts with a half step, which is instantly exotic (neither major nor minor does that), and twice again you get that wide step and a half (the ties above). The composer Saint-Saëns knew he could throw you into the ancient Levant for his opera Samson and Delilah by using the Byzantine scale:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEhor3HeulE” parameters=”start=9 end=34″ /]

Other minors and the modes down the road. Now go outside and play.