Radiohead and the Lament Bass

6 min text | 8 min music

One of my favorite Radiohead songs uses a technique with roots going back more than 400 years — the lament bass.

A quick bit of history, then Radiohead.

The lament bass started life as a thumb in the eye of Renaissance composers, especially madrigalists who overused a technique called word painting. Instead of writing a madrigal with one emotional reference point — joyful, sad, what have you — these madrigalists would reflect certain passing words of text with a winking musical illustration of that word. The word “high” gets a high note, “running” gets fast notes, and so on, even if it suddenly jolts you out of the emotion of the overall piece. The audience titters at the drollery, and the composer writes MOAR WORDPAINTING on his hand.

Sometimes it works well:

0:30

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95DJ7oqTWK8″ parameters=”end=30″ /]

That’s the madrigal As Vesta Was Descending from 1601. The word descending gets a downward run, ascending is an upward run. Later there’s a duet on two by two, a solo on all alone, and a long held bass note on the word long. It’s all harmless and cute for one reason: the word painting never contradicts the overall joyful emotion.

But to be a madrigalist in the 1590s is to never ignore your shoulder-devil, painting every word even if it wildly snaps you out of the emotion of the piece. A lyric like

Grief o’erwhelms my soul, tears flow like rain

Never again shall I be happy

So let me die now, alas

would start dark, then the word “happy” would suddenly repeat six times in up-tempo major, like Up With People crashing a wake, before returning to slow minor for the last line.

Listen to Carlo Gesualdo, The Mad Duke of Verona™, setting this actual text:

I die, alas, in my suffering,

And she who could give me life,

Alas, kills me and will not help me.

O! sorrowful fate

0:35

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6dVPu71D8VI” parameters=”end=36″ /]

Gesualdo murdered his wife and her lover, then wrote mournful music for the rest of his life by way of apology. Nobody does stab-me-in-the-heart, throw-me-down-a-well sadness like the Mad Duke. But he’s also a late Renaissance madrigalist, bless his heart, which means he can’t resist showing what a very clever boy he is. Even in the sentence “she who could give me life KILLS me,” the word “life (vita) goes into perky major cartwheels for a few seconds (0:16-0:30) before plunging back into sighs on “O! sorrowful fate.” That kind of crazy-quilt has no relation to actual human emotion.

The Renaissance also loved complex polyphonic textures (several overlapping melodic lines at once, like the “vita” section above), which buggers the text, which guts the emotional impact.

This elevation of cleverness over emotional clarity started to grate on some influential patrons of the arts, who were pretty sure that the music of ancient Greece and Rome was simpler in texture (one melody over a subdued accompaniment) and more emotionally unified. Their only evidence was ancient written accounts of music dramas being interrupted by audience members wailing inconsolably and throwing themselves off parapets. So these 16th century patrons gathered composers and theorists to discuss the problem of “music today” and to plot a new movement, one that assured a more unified emotional expression and much more parapet diving. Sad music would be sad from stem to stern, and peaceful music peaceful, and joyful joyful.

And lo! the Doctrine of Affections was born.

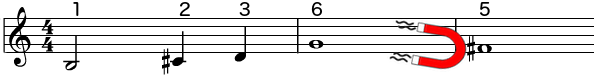

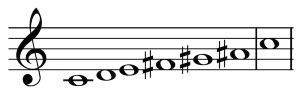

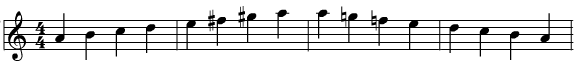

It was an idea meant to improve the expression of emotion in music. Simplify textures so lyrics could be understood. Keep tempo and rhythm consistent. Composers would choose an emotion from a list — Descartes suggested admiration, love, hatred, desire, joy, and sorrow — and stick to it. Keys were assigned specific emotions (C major is “rejoicing,” D major is “warlike,” G minor is “kindness,” etc.). A catalog of bass lines was created, each reflecting a different emotion. These eight notes, for example

signified “peaceful contentment.” Repeat the bass line for a peaceful, contented piece:

0:40

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfxrNblTr4o” parameters=”end=39″ /]

If you’ve been to a wedding, you probably know the rest.

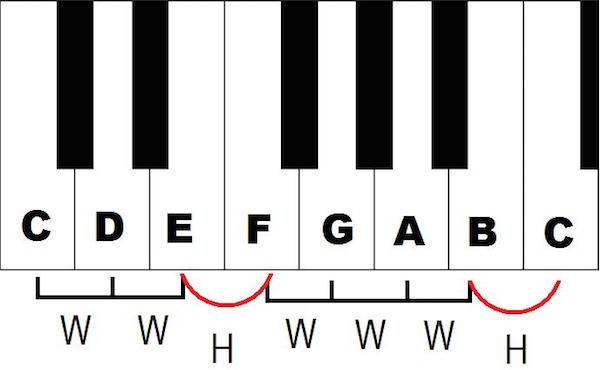

Sadness, on the other hand, called for a bass line descending by scale steps (like white keys on the piano) or half steps (white and black keys) from the first note of the scale to the fifth. Called the lament bass, this descending line is like a silk thread tying the chords together, creating centuries of smooth, gorgeous harmony.

Three Examples of the “Scale Lament”

Here’s a bit of Monteverdi’s Lamento della Ninfa (1620) with the repeating lament bass on scale steps.

0:38

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYdnUHCpomQ” parameters=”end=38″ /]

And a bit of Ray Charles using the same technique 330 years later:

0:22

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8Tiz6INF7I” parameters=”start=2 end=24″ /]

Even the Lord God his own damn self likes to wail over the lament bass:

0:36

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2QW2Wh1OZBA” parameters=”start=181 end=217″ /]

Four Examples of the “Chromatic Lament”

The chromatic lament uses all of the half steps (white and black keys) for even more emotional juice. Follow the pulsing notes in Vivaldi’s cello:

0:18

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3FmS4_fsau0″ parameters=”start=27 end=45″ /]

…or Mary Poppins, of all things:

0:13

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG6O4N3wxf8″ parameters=”start=7 end=21″ /]

Here is that same melting line in the brilliant “Butterflies and Hurricanes” by Muse:

0:21

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hucz0qsXEUQ” parameters=”start=8 end=29″ /]

…and of course “Stairway to Heaven”:

0:12

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9ioyEvdggk” parameters=”end=12″ /]

Radiohead’s Lament

Then there’s Radiohead.

A big part of my attraction to Radiohead is their wide spectrum of influences: Romantic harmony, New Orleans jazz, minimalism, punk rock, aleatory, non-Western — they reach into nearly every corner of the musical world. When the score for There Will Be Blood blew my hair back, and I thought I heard the influence of radical avant-gardist Krzysztof Penderecki in it, and then learned that Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood wrote that incredible score, and that he calls Penderecki his favorite composer…I thought, why not. That’s Radiohead.

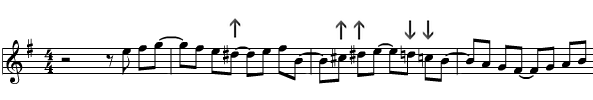

So I wasn’t surprised when a beautiful lament bass shows up in one of my favorite Radiohead songs, Exit Music (for a Film). Here it is.

4:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=50rlHVe6g9Q” /]

The lament bass starts right on the voice entrance at 0:23. It’s subtle the first three times, the lowest line of the guitar, but still serves the purpose of a silk thread linking and guiding the harmonies. And the last time (3:21) the lament shouts right on through.

There is so much more to the song: the Picardy third (a major I in a minor key) that ends each verse; the simultaneous Mellotron choir and the modulation to Pluto at 1:27, then the smooth slide back to Earth; that guitar tremolo countermelody at 2:50.

But it’s the lament bass that informs so much of the richness of this remarkable song. And at 3:21, it all comes together — Mellotron, tremolo, lament. Add the single melody over accompaniment, and it’s a perfect fit for the doctrine of affections — emotionally unified and effective from beginning to end.

I have seriously heard this a hundred times, and I’m going to listen again right now. That says something right there.

For more posts like this, follow on Facebook:

Feature image by Allesandro Pautasso via Flickr | CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; Thumbnail by angela n. via Flickr | CC BY 2.0

The Fifth Beatle Was a Robot

One of the most amazing things about (Western tonal) music is how much variety has tumbled out of a few basic materials. Twelve pitches in four triads in two main modes, maybe ten basic rhythms and a half dozen common meters and 20 instruments — shake well, and out pours Danny Boy and Mozart’s Lacrimosa and So What and Uptown Funk and the Nokia Tune and Sacred Harp 457 and madrigals and national anthems and this and this and god help us Happy Birthday. Millions and millions and millions of unique pieces created by repeatedly dipping a pan into the same stream, then picking through the nuggets.

What distinguishes one genre from another, or one composer or band from another, is the choices made among those nuggets. Handle harmony and rhythm and timbre in one way and you’re Bach, another and you’re Brahms, another and you’re nobody. Same with pop music. The reason you can tell the Stones from Coldplay is largely about the different approaches they take to the elements of music.

Scientists at SONY CSL Research Lab fed huge amounts of data from Beatles songs — choices made in harmony, melody, instrumentation, etc — into an algorithm that then composed a “typical” Beatles song. Uh…enjoy?

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSHZ_b05W7o” title=”Daddy’s Car: A Song Composed by AI” /]

It’s a little uncanny in that slightly queasy way, but I’ve got to admit — the essence is absolutely there.

So what is it that’s so bang-on Beatles-y?

There’s that rhythmic flow that starts at 0:05 (quarters in the drums, dotted quarter/eighth in the bass, eighth note strum in the rhythm guitar), the falsetto background vocals, the George Martin tubular bells, trippy background voices, all Beatles favorites. All good stuff. But it’s the harmony that our robot overlord has gotten (if I may say so, Your Excellency) exactly right.

[Be advised that the following includes theoryspeak. If that isn’t your thing, just listen at the times provided. You’ll get the idea.]

The drifty ahhhhh at the very beginning makes a slippery diminished triad. Which way is up, where is home? It doesn’t much help when the full harmony comes in (0:05): First there’s a triad that isn’t a triad (B C# F#), then an F# major triad, then A minor. It’s still hard to know where home is because no key contains both F# major and A minor chords. Then suddenly, boom, we’re in the key of B minor at 0:12, though the progression that follows is not at all typical.

We modulate to A minor (0:39), then to G major (0:47). A and G are close to B and to each other on the keyboard, but they are on different planets harmonically. So we have not only crossed into three different keys in under a minute, but three wildly unrelated keys, and gracefully at that.

Starting at 0:47 we get a progression that is all Beatle: G-A7-C-G, or I – V7/V – IV – I. Just listen to 0:47-1:07 and try to think of any other band. Then keep going a few seconds for the very cool jump back to B minor at 1:09.

“Down ON THE ground” (0:39- ) might be the most Beatlish spot in the whole thing. “ON” is a non-chord tone called an appoggiatura — a leap to a note that’s not in the chord, then a step in the opposite direction to resolve, something in a lot of Beatles songs — and it’s over a descending chromatic scale in wavery guitar, another fingerprint of theirs.

So if you wonder what made The Beatles The Beatles and everyone else everyone else — it’s mostly about the harmony. Sure, they wrote some four-chord pop songs. But the songs that really left a mark include harmonic adventures that no one else even approached. And even if you don’t know a thing about theory, you can hear it and feel it.

If you are fuming about the idea of a computer performing a credible facsimile of the human creative process, take heart. It’s easier to imitate than to create an original piece of genius. No robot has written the equivalent of “Eleanor Rigby” or “Because.”

Yet.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

The Most Essential Element of Music

Music is a hard thing to study or talk about for one big reason: it can’t stop moving. Aside from film, visual art tends to stand still, allowing the viewer some control over the experience. But music moves forward, relentlessly, thwarting our attempts to get a firm grip.

Suppose you tell a friend that you went to the Van Gogh exhibit at MOMA yesterday, and she asks, “How long was the exhibit?” The question doesn’t really make sense. At best, you’ll take it to mean, “How long does it take to go through?” That depends. Your answer could be six minutes, an hour, or all day. There isn’t a set duration for visual art.

But if you say, “I went to hear a Brahms concert yesterday,” and she asks how long the concert was, it’s a sensible question. Two hours and five minutes.

The difference is a critical one. At the Van Gogh exhibit, you could look at each painting for three minutes or skip entire rooms. Stand and gawk at “The Starry Night” for hours. Get in close for a look at one brushstroke. Step back, cross your arms pretentiously, and you can see the whole thing at once. You can compare one part to another, move your eye left and right and left again, top to bottom, leave the room for a potty break and come right back to looking at the waves crashing on the shore.

Stare at those waves for 20 minutes if you want. Realize they’re not waves. Compare background to foreground. Time is not a constraint.

Now on to the concert. The first piece begins. At any given moment you are experiencing only a fraction of the entire piece, one moment in time, and as soon as it happens it is gone, replaced by another and another in a sequence you cannot change. You can’t move your ears from left to right and back again at will, and you certainly can’t step back and look at the whole piece at once.

You also can’t stand up and yell, “Stop! Hold it right there so I can really listen to that moment!” Even if concert security doesn’t drag you out, holding one moment of the music destroys it. All you would hear is the chord at that moment, no rhythm, no meter, no tempo. All the elements of time, so crucial to making music what it is, are fatally suspended. You might as well try to understand the processes of the human body by saying, “Hold that heartbeat and breathing still for a few minutes.”

“If you take a cat apart to see how it works,” said Douglas Adams, “the first thing you have on your hands is a non-working cat.”

Visual art transmits meaning with shape and color distributed through space. Music transmits meaning with pitch and (tone) color distributed through time. This is the heart of the difference between music and visual art, and the heart of the difference in what each can and cannot do. The thing that makes music hard to study also gives it an advantage in capturing lived emotional experience. Like life, music flows.

Life unfolds, one moment after another. Plans are made, expectations built up, then they are fulfilled, or delayed, or dashed on the rocks, over time. The fact that music shares that critical element with life itself—that it unfolds gradually—is key to understanding its power to move us.

Click Like below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

Yabbut…Why THOSE Four Chords?

A few years ago, the comedy-rock band Axis of Awesome pointed out a great truth — that every pop song ever written uses the same four chords in the same order.

The fact that it’s not really true makes it no less impressive. I mean, every single song!

Enjoy a couple minutes of this, then we’ll talk.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/5pidokakU4I” parameters=”end=139″ /]

So maybe it’s not every song, but it is a helluva lot of songs using the exact same progression somewhere in it. The video puts them all in E major, which makes the progression

E – B – c# – A

Putting all of the songs in the same key is not cheating — it’s still the same progression, just like “Happy Birthday” is the same festering turd of a tune no matter how much helium you inhale. Likewise, this is the same chord progression no matter what chord you start on. If you’re in C, it’s C-G-a-F. If you’re in A, it’s A-E-f#-D. But it all boils down to this:

I – V – vi – IV

So why are songwriters addicted to I-V-vi-IV? Because for a basic progression, it’s actually pretty effective. Not a thing of genius, just a really solid workhorse. It’s been robbed of its sparkle by overuse, but it’s worth taking apart to see why it has become such a go-to.

I

It starts with I, the tonic, because most of the music you’ve heard, like most of the stories you’ve heard, starts at home. The question is where we go next. That’s easy:

V

As I said in The Hidden Grammar of Music, the most common place for any chord to go is up or down a fifth, and the tonic chord is no exception. In this progression, the I chord goes to the chord it is most closely related to, the dominant, the neon arrow: V.

Now the obvious thing for V to do is spring right back to I. Happens all the time:

The aforementioned “Happy Birthday” does exactly that. But a good chord progression (like a good sentence, story, meal, relationship) should include a little of the unexpected. Since we just did an obvious thing (I-V), we should do something less obvious next. So instead of going back to I, we go to

vi

Remember the deceptive cadence I introduced in the post about Cohen’s Hallelujah? That’s the idea. Instead of going home to I as it was born to do, V can go to vi, the relative minor. It’s interesting — a wee bit of shadow falls across the progression. And as the Hidden Grammar post pointed out,

Only one chord to go. But which one? We could repeat I, V, or vi, but that’d be boring. We want something new to round out the phrase. There are four other chords in the key. Which would be the most satisfying?

Here’s a thought: Each of the chords we’ve heard so far is made up of three pitches from the seven-note scale. When you rack up the pitches in those chords, we’ve heard six of the seven pitches:

You don’t know it, but your ear is thirsty for that missing fourth note. In the key of E, that’s an A. The chord built on that pitch is A major, or (ta-da!)…

IV

All together, then:

As a bonus, when you repeat the progression, IV goes back home to I in a very satisfying and common progression called the plagal or “Amen” cadence.

None of this makes the I-V-vi-IV progression inevitable, but it does make it sensible as a recurring thing, like subject-verb-adjective-object in written language.

Nutshell: If you start in the most common starting place, make the most common harmonic move, follow it with something just a little different, then fill in the one remaining gap in the scale, you get the most common pop progression on Earth.

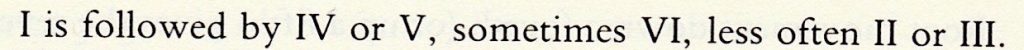

The Hidden Grammar of Music

I was 13 when I saw my brother’s college music theory textbook sitting on a table — Walter Piston’s Harmony. I had played clarinet and sax for a while, even did some arranging for jazz band. So I knew a little theory, but I was barely out of the blocks.

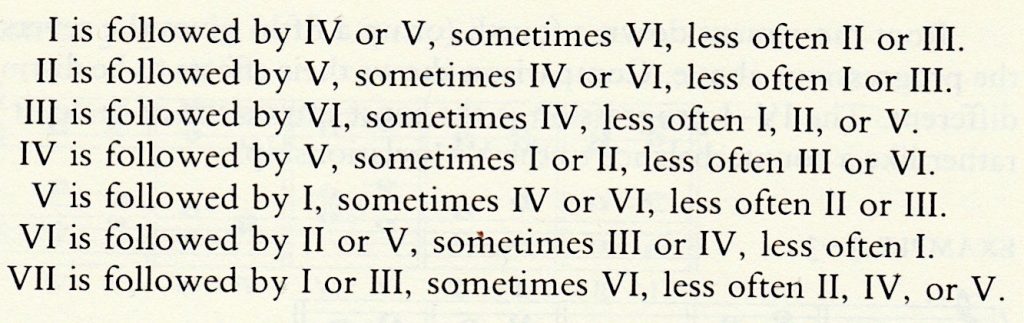

When I picked up the book, it fell open to a section called “Table of Usual Root Progressions.” Clickbait! I traced the words with a trembling finger:

Whoa.

If I’d known less theory, I’d have glossed right over it without understanding what it meant. If I had known more, I might not have been surprised by it. As it happens, I knew just the right amount to be gobsmacked.

It continued:

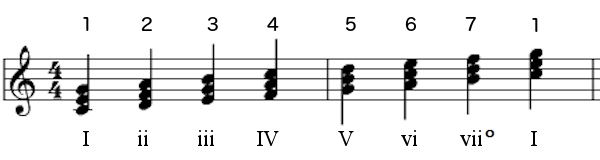

Here’s what it’s saying. Every key has 7 triads in it — 7 chords based on the 7 notes of the scale for that key. This is C major:

Now look down the left side of the Piston text: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII. These are the 7 triads of any key. (If you know some theory or read this post, you’ll know the Romans are usually upper case for major and lower case for minor. He’s making them generic for this example. Be not confused.) Each line is saying, “When you hear this chord, here are the chords you’ll most likely hear next.”

So for C major, you could rewrite the text like so:

The C triad is followed by F or G, sometimes A minor, less often D minor or E minor.

The D minor triad is followed by G, sometimes F or A minor, less often C or E minor.

And so on.

Here’s the thing: I had no idea there was a “most likely” order of chords. If I’d written a theory book when I was 13, it would have said

Chords are nice because they make the music fuller than just a tune alone. If you’re in the key of C major, the C triad should be followed by something different, because variety is the spice of life. GENESIS RULES! DM + KH 4EVER

I saw the chords as 7 different colors the composer could use, and yes, they are that. But it never occurred to me that there was this kind of hidden sense to it, a kind of grammar, like saying The subject is usually followed by a verb, sometimes by an adverb, less often by a prepositional phrase.

It was my first real glimpse below the surface of music. And then Piston did something lovely and rare in music theory — he explained why it’s that way.

When you move from any triad to another, there are only three possibilities: the chords have two shared notes, or only one, or none at all: Each of these has a different emotional quality. The first one is called a “weak” progression (though never to its face) because there’s only that small change between the chords, just one note different while two hang on. It’s like a sloth working its way through the forest canopy, moving just one limb at a time while the others stay attached.

Each of these has a different emotional quality. The first one is called a “weak” progression (though never to its face) because there’s only that small change between the chords, just one note different while two hang on. It’s like a sloth working its way through the forest canopy, moving just one limb at a time while the others stay attached.

When the roots of the chords (the note on which it is built) are a third apart, like C to E, you get that progression.

“Weak” doesn’t mean bad — sometimes a weak progression is just what you want for a tender moment, like so:

Here it is put to perfect use:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/J6xzL0TrsRY” parameters=”start=67 end=78″ /]

If all of the notes change, the feeling is more abrupt. There’s no connection between the chords. There isn’t a sense of smooth harmonic direction because the connection to the previous chord isn’t there. It’s a monkey leaping from one tree to another. You can’t easily tell where he leapt from.

When the roots of a chord are a second apart, like C to D, you get this kind of progression. The chord change at 0:38 is this type:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/eQAm7eZr920″ parameters=”start=17 end=45″ /]

And then there’s the engine that drives music. This is for chords with roots a fifth apart, like G and C, dominant to tonic. It’s Goldilocks, not too weak, not too abrupt: one note shared, two notes changing. It’s the perfect balance of continuity and dynamism, the monkey brachiating effortlessly through the rainforest of your mind, one hand back on the previous branch, a hand and a foot reaching forward to the next. And on he swings.

It’s called a circle progression for a great reason I’ll get to eventually.

When a composer wants you to feel direction on a large or small scale, the circle progression is the go-to. It flows like water. This aria from a Bach cantata is as good an example as any. The circle starts at 0:17 and ends around 0:30.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/3rKIc6QBCig” parameters=”end=31″ /]

Do you feel how the harmony was essentially marking time at the beginning, then starts rolling forward at 0:17? Circle progressions will do that to you.

The big news here is that harmony is spinning out a narrative beneath the melody. Composers use a mix of the three types of progressions to create an ebb and flow — moving forward, circling back, pausing, lurching, and sliding effortlessly in turn.

Now if you look back at the Piston text, it starts to make sense. No matter which of the 7 chords you’re on at a given moment, the most likely next step is a circle. That Bach progression is

I – IV – VII – III – VI – II – V – I

That’s all circle, and you can feel the tumbling momentum. But sometimes you don’t want that, so you’ll move by second or third, depending on the musical need of the moment.

Like all grammars, the real fun comes in busting out of the box — chromatic harmony, secondaries, modal harmony, polytonality, atonality, jazz harmony — but that page of Piston’s Harmony was my first step into the basic grammar of Western music. And it totally changed the way I saw my favorite thing.

Follow me on Facebook:

Harmony is What Happens to the Hero

As a kid, I knew chords were a lot of notes played at once. And I thought I knew why we had them: Melodies sound too plain by themselves, so we add chords to kind of fill it in, like the background of a painting.

I got better. The relationship between melody and chords (harmony) is much more interesting. We follow the melody like a hero. Behind and around the hero, the harmony provides an unfolding emotional story. It can be a simple home/away/home again story, or more of a leave home, get hit by bus, go to hospital, fall through trapdoor into your own bedroom and discover it was a dream kind of story.

The harmony is not just scenery — it’s what is happening to the hero. To understand how that works, we’ve got to get into the weeds a bit. Bear with me — cool toys are coming, and you’ll need these tools to play with them.

Each basic chord (or triad) consists of three pitches, like words consist of letters. Chords in combination communicate emotion, just as words in combination communicate meaning.

Keys don’t consist of seven notes so much as seven chords (triads). To build those triads, start with the seven notes of the C major scale (plus C again on top):

Now stack pitches on top of them in thirds.

Reminder: From one pitch to the next in the scale is a second, so C to E is a third, as is D to F, E to G, F# to Ab, etc. Doesn’t matter if sharps or flats are involved — it might be a different kind of third (major, minor, augmented, diminished), but it’s still a third:

Start with a note, add a third above it, then add another third above that one. You end up with stacks of three notes on the lines, or three notes in the spaces, like so:

These are the building blocks of musical meaning. Now let me add some information:

If it feels like the first time you looked at a periodic table, steady on — this is easier than it looks. Like the periodic table, it packs in a huge amount of powerful information once you know how to look at it.

The three lines of symbols contain different information about the triads. The digits on top are the simple degrees of the scale itself — the bottom note of each triad, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7, which in C major is C-D-E-F-G-A-B.

The bottom line is what you see on guitar music. These show the pitch on which each triad is based (also called the root of the triad) and the form the triad takes. Uppercase is major, lowercase is minor, and “dim” is diminished (more on that eventually).

The line of Roman numerals is just a way of combining the other two. The Arabic digit (like 5) becomes a Roman numeral (V), and the case of the Roman indicates major or minor. (The little degree circle means diminished.)

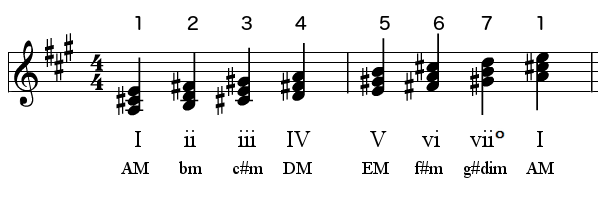

We can do the same thing with any starting pitch, any scale. The A major scale has C, F, and G sharped (raised by a half step) to fit the whole-step/half-step pattern of the major scale:

…and so on for any pitch, any scale. The chord symbols on the bottom change, but the Romans stay the same because the chords are fulfilling the same function in each key — the same “words” with a different home (I). I’ll be using the Romans a lot from now on to talk about what’s going on in the harmony of a piece. If I say the chords are I vi IV, it means you hear a major triad built on the first note of the scale, then a minor triad on the sixth note, then a major triad on the fourth note. But instead of 27 words, I use three symbols: I vi IV.

These three-note triads, much more so than the notes of the scale, are the emotional words of music, the bricks out of which everything is built.

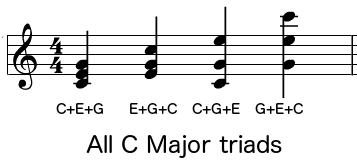

One important point: In the actual music, the notes don’t have to be in that order. They can be exploded out in any order top to bottom. This just reduces it to what’s called simple position, with the notes in the closest possible intervals to figure out what chords they are. Kind of like putting all the letters of a word in alphabetical order, except in music the meaning doesn’t change.

These are all C major triads, for example:

The composer might spread them out like that for different textures and effects. But if I want to figure out what’s going on in the harmony, I can put the last three in simple position with C on the bottom, and their harmonic identity becomes clear.

Okay, back to the triads of C major:

I remember being surprised to learn that a major key consists mostly of non-major chords. But it’s a good thing it does — that variety makes it work, giving you a road map so you know where you are relative to home. And your ear knows how to follow that map. Of course it does — you’ve passed this way ten thousands times before.

As the music moves along through time, left to right, it passes through different chords, and the sequence of chords makes us feel a certain emotional narrative. Same as language: These phrases start with the same three words, but the last three lead to very different places:

- For sale: baby turtles, too cute!

- For sale: baby shoes, never worn.

It works the same in music. Suppose you hear a major chord alone — let’s say it’s an F major triad:

Is that the tonic home? Dunno. It is if we’re in F major. But an F major chord could also be IV in the key of C. Can I get an amen, people:

Or V, the neon arrow, pointing to a Bb home:

In each case, before we could know what the F triad means, we needed another reference point. Once you have two chords, your ear starts to triangulate on home. Let’s say we hear two major triads next to each other, ascending — F major and G major:

When you look at the map for a major key, there’s only one place with two adjacent major chords, one place it fits in the aural landscape — IV to V.

And here’s the crazy great thing. You don’t need to see the map or know the Romans. When your ear hears an F major triad, then a G major triad, your ear instantly knows where home is. Sing it! You know where it’s going! Sing where it’s going, dammit!

C major is home.

So that’s a simple example of starting somewhere harmonically (F) and ending up at different homes (F, Bb, and C). That’s the tip of the tip of the iceberg. Composers use these ambiguities to mess with you, moment to moment, leading you to expect one direction and giving you another. It’s like those “garden path” sentences:

- The old man the boat; the young watch from shore.

- The man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

- The cotton clothing is made of grows in Mississippi.

- Mary gave the child the dog bit a Band-Aid.

Back to music for a while, including some unweaving that goes further into the harmony/hero relationship.

If you’re new here, or you want to review, you can start at the first post, or work your way through Just Enough Theory in the right sidebar. Quick and fun.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

A Minor Detour, To Jethro Tull and Bach

I want to write about the House of Cards theme, but first I have to talk about my obsession in middle school band. No, not the Hannah twins. I’m talking about a musical question that haunted me: Why is the melodic minor scale different going up and going down?

I know: If I had the head space to be haunted by the melodic minor, I clearly hadn’t read enough Camus. But I eventually figured it out, so I could turn at last to the fundamental absurdity of human existence.

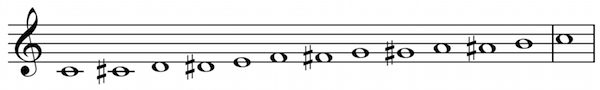

Here’s the A melodic minor scale:

Hear it? The 6th and 7th notes (or degrees) in the scale are raised on the way up (F# and G#) and lowered again on the way down (F and G).

To understand why that is, notice that melodic minor has melodic right in the name. It’s the scale that dictates the form pitches take in a minor key when they are in sequence, one after the other, like a melody.

The message of the melodic minor scale is this: if your melody is going upward, raise the 6th and 7th notes. If not, don’t.

That still doesn’t explain why. For that, you need to know one thing: notes are lazy.

Suppose a note is not in the chord of the moment — this is called a nonharmonic tone, more on that later — and it’s between two pitches that are in the chord. Moving either way would resolve the tension of being nonharmonic. But if one of those pitches is a whole step away, and the other a half step, the note in the middle will tend to move to the closer pitch, like an electron jumping to the nearest valence.

Remember Dorothy last time, hanging on that leading tone, windmilling her arms before reaching toward the tonic home a half step away?

That’s the power of the leading tone, just a tantalizing half step away from the tonic. Minor keys want a piece of that magnetic action too. But the 7th note of a minor scale is a big boring whole step from the tonic.

Nothing compelling there, no irresistible attraction to the tonic, no windmilling arms. To add to its humiliation, when the 7th pitch is a whole step below the tonic, it isn’t even called a leading tone — it’s the “subtonic.” Sick burn. It’s bumping elbows with the tonic, but not leading toward it in any particular way.

So instead, when a melody in minor is going from the 7th pitch to the tonic, it borrows the leading tone from major, raising 7 a half step, making it a true leading tone to the tonic:

Instant attraction!

Okay, but why is the 6th note raised? Because when you bump the 7th note up, the distance from 6 to 7 becomes a step and a half, a.k.a. an augmented 2nd, which stands out against the half and whole steps, sounding like Aladdin just magic-carpeted into the room:

Can’t have that. A lot of Western tonal theory is about creating a unified musical texture so you can respond to the emotional language of the whole without individual elements suddenly drawing your attention like passing squirrels. The absence of bagpipes in the orchestra, the rule against parallel fifths, and avoiding augmented 2nds are just a few of the ways traditional Western theory keeps your attention on the big picture.

So to avoid the augmented second from that raised leading tone, let’s raise the 6th note. This also keeps it from wanting to fall back to the 5th note, the powerful dominant, when you’re ascending. If you keep it lowered, it’s only a half step away from that delicious dominant, and that’s allllll it wants (10 sec, turn it up a bit):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRZAk2rfESU” parameters=”end=10″ /]

You feel that?? We’re in B minor here, so the top note G is the 6th, unraised. And each time you hear that unraised G, you can feel the magnetic pull down to F#, the dominant (5), just a half step below.

That’s great if that’s where your melody is headed, like it is in the Batman theme. But to break the pull and go up, you raise the 6th and 7th. Imagine after a couple of times through that motif above, Elfman wanted a triumphant ending. It might have sounded like this:

That time I raised the 6th to G#, which continued up to A#, then home to B. The line was going up, so 6 and 7 are raised.

These adjustments also just make minor melodies flow better as the 6th and 7th lean in the direction they are headed. Carol of the Bells is a great example:

9 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_LiccvcXdeI” parameters=”start=21 end=30″ /]

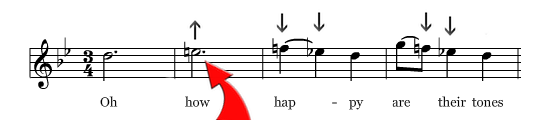

One note in Carol of the Bells gives me chills every time — a raised 6 as the tenors sing, “Oh how happy are their tones.” The word HOW is raised, then “happy are their tones” turns around and cascades over it:

5 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_LiccvcXdeI” parameters=”start=17 end=22″ /]

That spot, that one note, is thrilling, unexpected. Now you know why — it’s the sudden brightness of the raised 6th degree.

I’ll finish with the best example of the melodic minor in its natural habitat, one that takes me back to middle school again — Jethro Tull’s Bourrée:

15 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N2RNe2jwHE0″ parameters=”start=5 end=21″ /]

(I hear Bach did a remake of this, but I’m too much a fan of the original.)

Okay — now we can talk about House of Cards.

Home and the Neon Arrow

10 min

Just about every piece of music you’ve heard starts with a question: Where is home? A lot of the emotional power of the music, moment to moment and beginning to end, has to do with leaving home and finding our way back.

We’ve told this story for as long as we’ve told stories. It’s Gilgamesh, the Odyssey, and the Garden of Eden, the Hindu Muchukunda and the Welsh Gwion Bach. It’s Gone with the Wind, The Martian, Exodus, Battlestar Galactica, Gilligan’s Island, Gravity, Lost, Cast Away, all three Toy Stories (especially 2), Back to the Future, Planet of the Apes…and the films that elevated home-lust to a fine art: The Wizard of Oz and E.T.

In The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell suggested that every myth and legend we’ve ever told is a variation on a basic story he calls the monomyth. The hero leaves home, crosses into the unknown (usually by besting a guardian), meets a mentor, faces challenges and temptations, is transformed, and returns home, usually bearing a gift, totem, or special knowledge. Shake well and you get Prometheus, Star Wars, the New Testament, Lord of the Rings, and a million more.

I don’t know about “every myth,” but I get it. This narrative is huge.

Music works the same way. Composers establish home in a few ways, including the key, then they take you away. Sometimes it’s just a few seconds at a time — pop in on the neighbors, then home again, then out to the folks on the other side, then home again, all in a single verse. Or the music might take you for a long drive, then come back to the neighborhood, only to pull into the wrong driveway. It can also take you away from home and never bring you back. You start the day in F major, get stranded in D, and by the end of the piece, you’re stuck in the suburbs of B minor, working for an insurance company and living for the weekend.

I hinted at this in the scales post:

This pattern [of pitches in the scale] creates a kind of aural map. The sequence of half and whole steps sticks a pin in one of the notes, calling it home, then creates a series of landmarks to tell you where you are relative to that home at all times. By listening to music all your life, your ear has learned how to follow that map — to go away from home, have adventures, and return (or not). The next three JET posts will get into that.

And here we are, getting into it.

Part of the complex texture of musical communication is that all of this home-and-away drama happens not just on the scale of the whole piece, but measure by measure, phrase by phrase. There’s even the ability to encode different home-and-away messages in melody and harmony at the same time–I’ll show you how that works in a bit. As usual, you don’t have to know how it’s done, or even that it’s happening at all, for it to work.

But knowing is nice, so let’s do that.

First, a little proof of concept:

If you sang the last note like a little cheater, consider yourself Mozart. When he was 4, Mozart’s father is said to have rousted Wolfgang out of bed each day by playing the first 7 notes of the scale on the harpsichord, do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti… The slappable little prodigy would leap out of bed, unable to bear the musical unresolvedness of it all, run into the parlor, and play the last note: do!

Whatever.

True or not, the story rests on a true thing: the 7th note of the scale is fabulously unstable, known perfectly as the leading tone. It’s the last thing before you get back to the key note, which is “home” in music. You can feel home right next door. Not only that, it’s just a half step away from the tonic home. So the leading tone feels like it’s standing with its toes over the edge of a cliff, windmilling its arms, trying to keep from toppling forward onto the tonic. And not trying all that hard.

Dorothy’s final “can’t” (Why oh why caaaaaaan’t…) is on a leading tone.

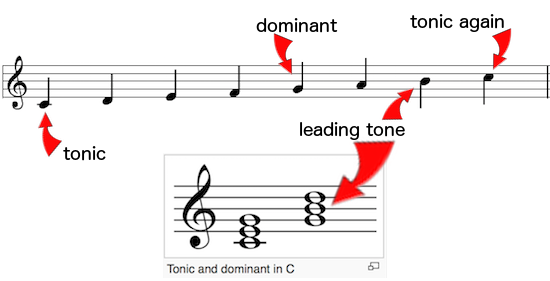

But for all its cliff-edge windmilling, the leading tone isn’t where the real home-pointing power is. There’s another relationship that’s more important for deep emotional direction. It’s the tonic’s relationship to the 5th note of the scale, known as the dominant. The chord built on that pitch is a big neon arrow pointing home. If you’re in C, then C is the tonic and G is the dominant:

Listen to those last three notes, 1-5-1. The first note is home. The second note moves away. The third feels like a return home, back to the center of the tonal universe.

But single pitches are just a shadow of the real juice–the harmony. Build triads on those pitches and you can really feel it. Triads are designated with Roman numerals, so the chords built on the pitches 1-5-1 are called I-V-I. Here’s what that sounds like:

Sounds simple to the point of boring, right? But it’s epic, one of the main reasons music works. That second triad isn’t just a generic “away” — you can feel a magnetic pull back to home.

Let’s put it in context, melody plus harmony, with three short phrases you know. I hold the V a bit in each one so you can feel it jonesing to get home:

That’s right — Dorothy’s “can’t” has a leading tone in the melody, and a dominant in the harmony. It’s yearning for home in both ways.

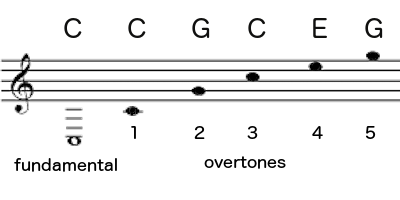

So why the special relationship between V and I? It’s the overtone series. Remember this?

In the overtone series, the fifth note of the key is the strongest pitch you hear. That’s why the fifth is the most basic pitch relationship after the octave. The G is embedded in the sound of C. Sure the leading tone is just a half step away, but emotionally, the dominant pitch is the closest thing to home. So as Western music developed its grammar, that relationship of a fifth, tonic to dominant, became the emotional center — home, and the neon arrow pointing home.

In the overtone series, the fifth note of the key is the strongest pitch you hear. That’s why the fifth is the most basic pitch relationship after the octave. The G is embedded in the sound of C. Sure the leading tone is just a half step away, but emotionally, the dominant pitch is the closest thing to home. So as Western music developed its grammar, that relationship of a fifth, tonic to dominant, became the emotional center — home, and the neon arrow pointing home.

Add the fact that the dominant chord has the leading tone in it, and you’ve got both a harmonic and a melodic magnet to home.

Composers can do wonders by promising home, then fulfilling, delaying, or denying that promise, or fulfilling it in the melody but denying it in the harmony, and on and on.

The Phillip Phillips song “Home” plays with the concept, and no surprise there. In the second verse, “Settle down, it’ll all be clear,” the harmony is on the tonic chord, but the melody floats up away from home, away from the tonic pitch:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HoRkntoHkIE” parameters=”start=45 end=61″ /]

The next phrase (“trouble it might drag you down”) could have been boringly stuck at home on the tonic in melody and harmony:

Instead, when the melody drops down to the tonic on the word down (“trouble it might drag you DOWN”), the harmony moves away from home. It’s cat and mouse:

Hear the difference? All through that verse, melody and harmony don’t find home at the same time until a strong downbeat on…what word? Yeah:

I’m gonna make this place your HOME.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HoRkntoHkIE” parameters=”start=61 end=79″ /]

Whether the composer was literally thinking of the lyric “home” and matching it with the tonic, who knows. But no decent songwriter stumbles accidentally on the home-and-away syntax of music. They know just what they want emotionally, and the home-and-away dynamic of Western harmony gives them the tools to achieve it.

Consonance is Nice. Dissonance is Delicious.

15 min

This is Your Brain on Music is a really good book about the neuroscience of music. There are about 4,000 good sentences in it. So it might seem petty to talk about the one sentence that made me sad, but that’s how sad it made me:

Musicians refer to pleasing-sounding chords and intervals as consonant and the unpleasing ones as dissonant.

Be a love: Take a Brillo pad and scrub that sentence from your monitor. If you have the book at home, scrub it out there as well. Page 62. I’ll wait.

[…]

By the end of this post, I hope you’ll see how tragically wrongheaded it is to call dissonance “unpleasing”. The really effective, moving moments in music almost always include dissonance, sometimes a lot of it, just as the really effective rollercoasters almost always include hills. These aren’t bugs–they are features.

I mean gah.

A flat rollercoaster and dissonance-free music are so off-point that they are given completely new names, like “light rail” and “Enya.” Good for getting you massaged and moving you from place to place, maybe, but not for moving you. The interplay of dissonance and consonance, tension and release, is one of the ingredients that makes Western music work. It’s a sliding scale defined by more or less complexity in the relationship of pitches.

Pitch combinations aren’t just “consonant” or “dissonant” — like everything we seem to talk about here, there’s a spectrum. So please keep your arms inside the car as we head into that spectrum.

Some Quick Terms

The distance between two pitches is an interval. If it’s one note following another like a melody, it’s a melodic interval. Two notes at the same time is a harmonic interval. That’s where the real emotional juice is.

Intervals are named by the distance between the notes. From any note up to the very next note name is called a second. Skip one and it’s a third. Skip two names and it’s a fourth, and so on. So in the scale below…

…C→D, E→F, and A→B are all seconds. C→E is a third. C→F is a fourth. C→A is a sixth.

What about flats and sharps? C→D♭ is still called a second because it’s going from one pitch name to the next. But it’s a minor second (or half step), the Jaws interval, duh-dump. C→D is a major second (or whole step), the Chopsticks interval, which is less dissonant than the minor (depending on the child and the piano, I guess). And C to G♭ is still a fifth, but a diminished fifth, a.k.a. a tritone, a.k.a. “the devil in music,” about which more below.

If this were my theory class, we’d now drill intervals for two weeks. You’d learn how to identify and spell minor, major, perfect, augmented, and diminished intervals starting on every pitch. You’d bite back your tears, determined to meet the interval on its own terms, driven by grudging respect for my lunatic quest for perfection.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnuImW1dWAk” parameters=”start=87 end=103″ /]

But we’re doing Just Enough Theory here, so we’ll skim lightly over the cool surface, emphasizing dissonance, with the Devil as our special guest.

Consonance and Dissonance

The technical explanation of consonance and dissonance is the ratio of vibrations of the two pitches.

The ultimate consonance is a unison. It’s not harmony — just one note playing with itself, which is sinful. The ratio is 1:1. Add another pitch and you get intervals.

Octaves, fifths, fourths, and thirds are very consonant. They sound like this:

Simple vibration ratios are consonant, in part because there’s a lot of matching and little close conflict in their overtones. The [tippy title=”octave”](‘Some-where’ [over the rainbow])[/tippy] is the most consonant (besides the unison). The top note vibrates twice as fast as the bottom, a simple ratio of 1:2. A fifth is a ratio of 2:3, and a fourth is 3:4, etc.

That’s the technical explanation. But the most important thing is that you can hear it. Here’s some [tippy title=”real consonance at work”]Aaron Copland, Fanfare for the Common Man[/tippy]:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/4NjssV8UuVA” parameters=”start=22 end=52″ /]

Hear how open, relaxed, stable, and confident everything is? That’s because there’s little conflict between the pitches, no complex vibrations.

Now let’s get dissonant:

These are more tense, less stable. You can hear a lot of conflict between the pitches, which makes these relatively dissonant. They “want” to resolve to a more consonant interval, which drives the drama in music. And the ratios are getting complex — 8:15, 8:9, and a wickedly cool √2:1, respectively.

That last one is especially interesting. It’s a tritone, an internal three whole steps across (hence the name). It divides the octave exactly in half, so you’d think it would be consonant. But when you can’t even express the ratio without resorting to irrational numbers, you know you’re not in Kansas anymore.

Sure enough, the extreme dissonance and instability of the tritone has been recognized for a thousand years at least. Monk and music theorist Guido d’Arezzo called it Diabolus in musica, “the Devil in music.” The tritone loved that and immediately had it tattooed on its lower note, at which point it was banned from church music for several centuries (true dat).

But before we make the leap from “tense and unstable” to “unpleasing,” let’s put them in context. Here’s a minor 2nd, first alone, then in context:

And here’s a tritone in two very different settings — one romantic, one funny:

See? Of course the tritone CAN be damned unpleasant when it needs to be. Turn it up to freak out your dog:

And here’s one you’ll recognize from childhood:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/Jtie6r27JeU” parameters=”start=26″ /]

The brass start with a tritone, then the Witch’s Guards come in singing a fifth — yo ee oh…yohhh, oh, or whatever. The combination is confident power (5th) + sinister threat (tritone).

But back to dissonance being amazing. Here are four short excerpts with nearly continuous dissonance. These are some of my favorite passages on the planet, so if you skip it, don’t tell me (under 3 min):

2. Bartok MSPC, mvt. II

3. Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring

4. Charles Mingus, Don’t Be Afraid, the Clown’s Afraid Too

And dissonance goes way beyond that. Epitaph for Moonlight by the Canadian composer Murray Shafer pushes pitch just about as far as it can go, and he does it with the human voice. Follow the pencil (4:38):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/l1SlyJ2kreI” /]

I know that’s not everyone’s cup, but boy is it mine.

Music without dissonance…well, just imagine a drama, or even a comedy, entirely devoid of conflict. That would be unpleasant. It might make for nice lunch conversation, but it doesn’t make for good theatre. In addition to being rich and beautiful on its own terms, we need dissonance to give consonance its raison d’être. Sliding the level of tension up and down the continuum of consonance and dissonance by combining pitches, intervals, and chords is one of the critical emotional tools of the composer.

And even if your tastes don’t run as dissonant as mine, believe me — you wouldn’t want to do without it.

Follow me on Facebook:

Scales! Wait. Come back.

I hated scales in middle school. Oh I was good at scales, even got a certificate for playing all four forms of every scale by memory on my wee clarinet. I was a good boy.

And still I hated them.

It just seemed like such a pointless, hoop-jumping thing to me. Memorize these note patterns, then play each one starting from every possible note, and you win. But aside from the value of rote memorization and the fingering practice…what was the point?

There were other unanswered questions in my head — like Why are there three different kinds of minor scales? Why is the melodic minor different going up and going down? Why does the harmonic minor make me sound like a snake charmer? Why does minor sound sad and major sound happy? Are these the only four ways to get from C to C?

It’s like the Steven Wright joke

Why is the alphabet in that order? Is it because of that song?

Scales are actually cool and interesting once you know what they’re for. Stick with me to the end of the post, then tell me if I’m wrong. (Spoiler: I’m not.)

Last time I split the octave into 12 equal parts to make the chromatic scale. The name hints at the purpose. By containing all 12 of the pitches we use in Western music, the chromatic scale is like a paint store with 12 available colors.

You don’t want every available color for a painting project. You choose a palette — a subset of colors, a theme. If you want this result:

…don’t use every color in the store. Use this palette:

Same for music. The chromatic scale has every available pitch in the Western tonal system. The distance from one to the next is a half step. Here are the 12 half steps of the chromatic scale (plus the next C):

When I write a piece, I don’t need every note. If I want a certain mood, I’ll choose a subset of pitches from the 12 available, and a different subset gets me a different mood.

Example: If I choose every other pitch, instead of 12 notes a half step apart, I’ll have 6 notes a whole step apart. That’s called a whole tone scale:

There’s something strange about that scale, right? It starts going off the rails at the 4th note and never gets normal again. Here’s why: All of the pitches are the same distance apart. No half steps. Because of that, your ear can’t easily track where you are. Aside from whatever note we happen to start on, none of the pitches stands out as “home,” so the whole tone scale creates music with an ethereal, directionless quality. If you were a child of the 70s, you know it well. Whenever there was a campy flashback in The Brady Bunch, or Scooby Doo was being hypnotized, there’s a good chance a harp or bells were playing music drawn from a whole tone scale:

One particular Debussy piano piece called Voiles (Sails) is the go-to for illustrating a whole tone scale. Feel that unanchored, homeless quality (0:47):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95_OvaRHwDg” parameters=”start=9 end=56″ /]

The fact that pretty much every theory teacher uses sitcom flashbacks and one Debussy piece as whole tone examples shows you just how rare it is. Beyond drifty sails and coming unstuck in time, a scale with all the pitches equally spaced just isn’t all that useful. If someone gave you driving directions like this — Go one block and left, one block and right, one block and right, one block and left, one block and right, and on and on across town, you’d have a helluva time finding your way home again. Every step is the same. It’s confusing.

If instead the directions were Go one block and left, three blocks and right, one block and left, then five blocks and you’re there — now the steps are different enough to landmark in your head. You need a scale that works the same way — a mix of steps of different sizes so your ear knows where you are relative to home.

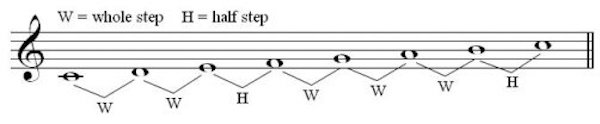

Major and minor scales do just that, creating a pattern of pitches that are different distances apart. They do it by choosing only 7 of the 12 notes, leaving gaps where the other pitches were. The scale shows the ladder of steps between the notes if you arrange them in order. Here’s a C major scale:

You start on C but leave out C# and go to D — a whole step. It’s like going from red to orange and skipping reddish-orange. The major scale then goes another whole step (to E), then a half step (F), then three more whole steps (G-A-B), and finally a half step to the next C. If you start on C, the white keys on a piano fall naturally into the major scale without any adjustments. The black keys are the gaps, the five chromatic pitches that were left out of the major scale:

If you start on a note other than C, you’ll have to raise or lower notes along the way, using flats and sharps on the page and black keys on the piano to get the same pattern of whole steps and half steps.

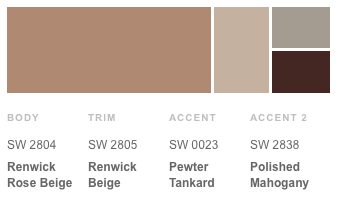

Scales aren’t meant to be played in that order any more than the letters in a word are supposed to be spelled out in alphabetical order, or a set of colors in your paint theme is supposed to be painted left to right on the wall by wavelength. Hey, rainbows are great, but you don’t want a rainbow every time you paint. So when you paint your house, this is the scale:

…and this is the music:

The scale is a set of instructions to pick out the colors (pitches) that establish a certain palette (key) for the music you want to write.

But music goes beyond the visual analogy to something that makes its emotional power possible. This pattern also creates a kind of aural map. The sequence of half and whole steps sticks a pin in one of the notes, calling it home, then creates a series of landmarks to tell you where you are relative to that home at all times. By listening to music all your life, your ear has learned how to follow that map — to go away from home, have adventures, and return (or not). The next three JET posts will get into that.

The minor scale is a different pattern of whole steps and half steps spanning the octave. The result is a different emotional palette:

The minor scale results when you lower the third, sixth, and seventh pitches of the major. That’s worth remembering. No need to memorizing key signatures or build scales yourself, but we’ll certainly talk about the various shenanigans the third, sixth, and seventh notes of the scale get up to.

Three great scales from elsewhere

Step outside of Western music and you can really start to see how different scales color the music. I hinted at that last time with the Carnatic microtonal scales. (Don’t be skipping stuff, or all is lost.) Here are three more.

Arabic music has at least 90 different scales, or maqam, each of which provides a different mood. Here’s one, maqam nawa athar:

Which sounds like this:

Hear that? It’s just crammed with intervals that sound exotic to Western ears. If a major scale is a map across your hometown, this one is a map to the market in Marrakech.

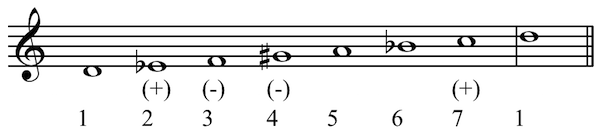

Several of the pitches of the Indonesian pelog scale fall in the gaps between our notes, which further shows that all scale divisions are arbitrary and cultural. You can’t even notate pelog properly with Western notation. If you try, you end up with these apologetic little plus and minus signs to indicate “a little higher” or “a little lower” than the notation:

And why not? Remember the sixth overtone, the B-extra-flat? To Western listeners, these pitches sound out of tune because they don’t match our particular divisions, but they have no less claim. Here’s pelog:

And here’s a phenomenal Balinese gamelan playing music using a variant of pelog. If you haven’t heard Balinese gamelan before, strap in, this is awesome:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ldPMifPbngc” /]

Want to evoke a Middle Eastern vibe? Use the Byzantine scale:

It starts with a half step, which is instantly exotic (neither major nor minor does that), and twice again you get that wide step and a half (the ties above). The composer Saint-Saëns knew he could throw you into the ancient Levant for his opera Samson and Delilah by using the Byzantine scale:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEhor3HeulE” parameters=”start=9 end=34″ /]

Other minors and the modes down the road. Now go outside and play.