Yes, ‘Stairway’ Was Stolen…Just Like Everything Else

- June 26, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

A jury decided that Led Zeppelin did not steal the iconic opening measures of “Stairway to Heaven” from a passage in the song “Taurus” by the band Spirit. Some people think Zeppelin got away with murder, arguing, “Well just listen to it, jeez!”

In fact, they got away with composing.

Whole-cloth ripoffs like “U Can’t Touch This” aside, the idea that it’s wrong to use a string of notes someone else once used in a similar way stems from a modern misunderstanding of how music is created — the unhelpful romantic myth that every new piece of music is a unique snowflake crafted from the purrs of unborn kittens in the soul of the composer.

In fact, nearly every piece of music you love is made up of 99.9 to 100% recycled materials. That’s not an accident: Composers return again and again to the shapes and patterns in our established musical lexicon because that’s what composing is.

Yes, there are exceptions — mostly radically avant garde pieces that try to make a virtue out of keeping you perpetually balanced on the back legs of your chair. That approach leaves a pretty narrow range of emotional states to explore, things like anxiety and puppy-slapping irritation. Once you’ve rejected all shared musical language, you can mostly forget slowly unfolding emotional experience.

To see what I mean, and why the Stairway lawsuit (and Blurred Lines, and Creep, and yes, even My Sweet Lord) was dumb, let’s take a peek into the workshop.

A Big, Finite List

Most Western music derives from a finite number of raw materials. It’s a big number, but still finite. You have 12 pitches arranged into two main scale types (major and minor), with occasional side trips into five others.

Western harmony is based on triads — three notes stacked in thirds. There are four kinds: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. You can also keep stacking thirds, adding a 7th, a 9th, or an 11th to the triad, and so on.

When a pitch sounds that isn’t in the chord of the moment, it’s a nonharmonic tone, of which there are about 12 types — passing, neighbor, suspension, anticipation, and so on.

Pitches arrange themselves over time in meter and rhythm. Each beat can be divided up into smaller bits, usually in 2, 3, or 4 parts, sometimes something stranger like 5. The most common meters are recurring bundles of 2, 3, or 4 beats called measures, sometimes 6, less often 5, 7, 9, or even 33 beats per measure.

Measures are usually in groups of 4 called phrases. Though it’s rare to have a piece based entirely on three- or five-bar phrase lengths, one of the best emotional devices in music is an occasional abbreviated or extended phrase. Nicely messes with your expectations.

The tonic chord usually goes to V or IV, sometimes to iii or vi, less often ii or vii. Mixing the usual with the unusual is the crux of the game.

Different genres of music have certain core instrumentations. A rock band usually has a guitar or two, bass, drums, and vocals. Sometimes a keyboard. Sometimes horns. Sometimes a flute or banjo. Orchestra has ABC, funk band has DEF, polka band has XYZ. So within a certain genre, the choices are even more constrained, and the similarities between pieces multiply.

On it goes, a large but finite set of variables in pitch, meter, rhythm, instruments. The amazing thing is that such an incredible variety of genres and songs has come out of this large but finite set.

Within the choices available are patterns and combinations that produce certain emotional effects — tension, calm, dread, humor, gravity, power, violence, aspiration, momentum, flight. The existing set of musical elements is drawn on over and over by composers to produce these effects in the same way a million writers dip their buckets into the shared well of language, drawing out existing words and phrases and allusions to produce the effects they need.

When writers need to evoke “bittersweet yearning,” they don’t start cobbling together letters into new combinations to see what might feel both bittersweet and yearny. They draw on the large but finite set of words and phrases that have already been used to capture that feeling.

Music works the same way. You want bittersweet yearning? Try a I-iii progression. It’s been done a thousand times, but that doesn’t mean I can’t do it again, a little differently, and create something that is new but (here’s the point) not unique.

The idea that each piece of music arrives fresh from the sea foam like Aphrodite on the clamshell, and that it must evoke no other existing song, is both detached from reality and paralyzing to the songwriter. When I studied composition, I can’t tell you how many times I sat down at the piano to come up with the germ of an idea, plunked out three notes, and said, Nope…Stravinsky. Three more notes: Nope…Bartok. Frustrated silence: Nope…Cage.

It’s a weird modern conceit. Bach did not tinkle out a phrase and mutter, Nee… Buxtehude. Nee…Couperin. Sheiße! Nor did he write music that had already been written. He used and adapted patterns and combinations that almost always had been used before. You use them in new ways, extend them, evolve them — but you don’t set out to utterly avoid every resemblance to what already exists. The whole idea is bizarre. It seems like it’s encouraging originality, but it’s actually deeply anti-creative.

The Case of Stairway v. Taurus

Stairway to Heaven is exactly as “stolen” as everything else you’ve ever heard. When he sat down to write the song, Page drew on existing materials and norms to create something new. Randy California did the same when he wrote Taurus. In the process, they crossed into similar territory for a few bars.

Both started with the commonest clay: 4/4 meter, the key of A minor, and an acoustic guitar outlining the chords in straight eighth notes and four-measure phrases — each choice so common as to be essentially the default.

Then they both chose a device that’s rich and evocative, and not original to either of them: a descending chromatic bass line (going down by half steps). It’s a device so well established that it has a name — the “lament bass” — and variations of it pop up in everything from Bach’s “Crucifixus” to the Beatles’s “Michelle” to “Chim Chim Cher-ee.” Follow that bass line (13 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG6O4N3wxf8″ parameters=”start=7 end=20″ /]

So the descending chromatic bass isn’t default, but it’s a well known device. The question as always is what you do with it. The composer of “Taurus” did this (28 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xd8AVbwB_6E” parameters=”start=44 end=72″ /]

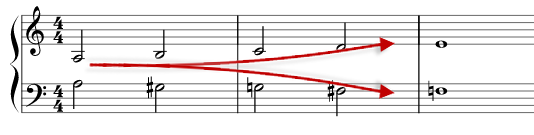

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

Here’s what Page did with the same bass line (27 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9ioyEvdggk” parameters=”end=26″ /]

That’s greatness. In addition to the descending bass, Page laid an ascending scale into the upper line (circled notes). Sometimes a pitch is displaced by an octave or off the beat, but your ear hears the ascending line. This creates a wedge that slowly opens — unison, third, fourth, sixth, and finally that delicious major seventh — before returning to the unison/octave:

I’ve pulled out the lines so you can hear them better:

The result is a nuanced, haunting passage written by an artist who knew what he was doing. And this doesn’t even crack open the inspired work in the next hundred measures. I might come back to that.

So: was Stairway directly inspired by Taurus? Who knows. In a better world, Page could stand up and say, “That’s right, I got the idea straight from Taurus. Then I made it better. That’s how this bloody thing works.” And composers would stop suing other composers for composing.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Full songs: Spirit, Taurus; Led Zeppelin, Stairway to Heaven

Jimmy Page image by Dina Regine via Flickr | CC 2.0

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Isn’t It Iconic?

A University of London researcher has found something we didn’t even know we were looking for: the most iconic song ever written. After announcing his choice, he was moved to an undisclosed location.

If the comment sections are any indication, a lot of the complaints are due to a misunderstanding about the researcher’s claim. He didn’t claim to have found the best song, or the most powerful, moving, or effective one. Dr. Mick Grierson was looking for the most iconic.

To qualify as iconic, he says, a song has to be well-known and distinctive. If it’s famous but very similar to a lot of others, it isn’t distinctive, so it can’t really be iconic. And a very distinctive song still isn’t iconic if few people have ever heard it. It might be to you, but not to the culture at large.

Even understanding that, I was mystified by the result — until I discovered something hiding in plain sight.

Grierson created a credible list of the 50 best-known songs using lists from magazines like Rolling Stone. To assess “distinctiveness,” he used computer software to analyze some elements of the music itself. Of the 50 songs:

- 80% are in a major key (mostly A, E, C and G)

- Average tempo is 125 beats per minute, a brisk walking tempo

- Average length is 4 minutes on the nose

- Average number of different chords is 6-8

He also looked at something he called “spectral flux,” which he said is “how the power of a note from one to the next varies.” I’m not sure what he means by that, but I’m guessing it has to do with variation in tone color and intensity.

Another variable called “tonic dissonance” apparently refers to the use of pitches outside of the key, i.e. non-harmonic tones.

So what he wanted was a song that was famous but departed from the norm in a number of these quantifiable ways. A minor key would count as departure, as would unusual tempo or length, or greater than average number of chord changes, or frequent changes of timbre, or a lot of pitches outside of the key.

So what song did he and his computer decide is the most iconic of all time? Nirvana’s 1991 hit Smells Like Teen Spirit.

I…wut.

I’m not one to howl when the particular headbanger anthem that got me through puberty doesn’t make somebody’s Top Ten list. I’m on the side of truth and justice for this one, no skin in the game. In fact, I really like Teen Spirit, especially the way the melody leans into unexpected pitches, and that contrast between quiet lethargy and full-throated entitlement. More emblematic of a generational moment than most songs making that claim. I can even see it in the top 50 iconics, why not. But by the study’s own stated variables — not just my preferences — I couldn’t understand how it qualified as Most Iconic.

Let’s compare Teen Spirit to two other songs that were lower on the list.

#1. Smells Like Teen Spirit – Nirvana (1991)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGqDQKLUXko” /]

Most of the top 50 are in a major key, and Teen Spirit is minor. One point for iconic.

The tempo is 116 beats a minute, close to the average of 125. The length is 4:35, just over the average of 4:00. Two points for typical.

Harmonic diversity is slim. Aside from the kind of silly 4-bar bridges at 1:23 and 2:38, the whole song appears to be the same four chords in the same order: F minor, Bb, Ab, and Db.

Hey wait a sec: they aren’t even chords. Chords have at least three pitches. These are something guitarists call “power chords,” a rock staple (i.e. “not iconic”) that removes the third from every chord. So instead of F-Ab-C, it’s just F-C, and so on. It’s a really powerful, raw sound, but it reduces the already poor pitch diversity even further.

If we take out the little 4-bar bridges — a total of 16 seconds — Teen Spirit doesn’t have even one pitch outside of the key, which is pretty low tonic dissonance. Include the bridges and it has just two such pitches.

Variation in timbre is there, but moderate. An effective toggle of atmospheres between the mumble and shout sections, but it’s still drums and guitars from start to finish.

I love the song, and it’s Top 50 iconic. But not #1.

#15. Stairway to Heaven – Led Zeppelin (1971)

Play a minute or two as you read:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXQUu5Dti4g” /]

Despite a minor key, a distinctive harmonic language, a rhapsodic structure, and an 8-minute duration (for which I and all other teenage slow-dancers of the 70s and 80s are grateful), this iconic rock song came in 15th.

Within seven seconds, Stairway has already exceeded Teen Spirit in harmonic variety. It starts with a progression of five different chords over that (yes) iconic chromatic bassline, including an augmented triad and a major-major 7th chord on VI.

Tempo structure is also unique. It starts at 76 beats a minute, way off the average. When the drums enter for the first time at 4:19…well, first of all you say, “No drums for four minutes and 19 seconds! How iconic!” Then the tempo picks up a click to 84. Around 6 minutes, it goes up to 96. It’s a nice effect, a slight acceleration over time that helps sustain the long form.

As for tone color, dynamics, and other “spectral” aspects, Stairway moves through multiple sections, from acoustic guitar and a consort of recorders (iconic!) to electric guitars and a shout chorus before ending in a quiet solo a cappella.

Finally: Did the researcher even try making out to Smells Like Teen Spirit? You’d end up on a pile of bloody teeth. Stairway for the win.

#5. Bohemian Rhapsody – Queen (1975)

Play a minute or two as you read:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/fJ9rUzIMcZQ” /]

For pure iconic differentness, it’s Bohemian Rhapsody in a walk. A six-part rhapsody form moves from a cappella ballad to Gilbert and Sullivan operetta to hard rock and back to ballad, changing key at every gate.

But we don’t even have to look that far to beat Teen Spirit. In the introduction alone, Rhapsody has nine different chords, including an added sixth chord (0:05), a secondary dominant 7th (0:09), chromatic neighbor chords (0:37), and a fully-diminished secondary leading tone 7th chord (0:47). AND it changes key after just 25 seconds.

Talk about awesome tonic dissonance –all that, and all 12 notes of the chromatic scale, and we’re less than one minute in.

The pretty obvious thing I missed about Teen Spirit

But wait a minute.

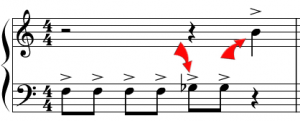

There’s another chord in Teen Spirit. It doesn’t show up in the chord charts, and it has always slipped right past my ear. It’s a chromatic passing chord, the very last thing you hear at the end of the first bar (4 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGqDQKLUXko” parameters=”end=4″ /]

Tiny detail, right? It is to us humans. But here’s the thing: We’re in F minor, so both of those notes (E and A) are outside of the key. And it appears not once, but about fifty times, in alternating bars for most of the song! To you and me, it slides on by. But a computer analyzing for pitch variety will hear a song positively soaking in “tonic dissonance.”

Still, that’s only eight notes out of 12. We’re still missing Gb, G, B and D.

But wait! What about those two ugly notes in the bridge? (3 sec)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGqDQKLUXko” parameters=”start=91 end=93″ /]

Dude, no weh! It’s Gb and B. Add the excellent G Kurt is always leaning on

and Smells Like Teen Spirit has 11 of the 12 chromatic pitches, including a constant saturation of those two pitches outside of the key.

But here’s the thing: Except for the vocal G, they just aren’t significant. Unlike Bohemian Rhapsody, for example, the unusual pitches are mostly incidental — a passing tone on a weak beat. No matter how often it happens, it isn’t significant enough to raise a song to iconic status. Our brains can sort between significant pitches and incidental ones. But to a computer counting the frequency of frequencies, it’s all the same.

That’s why Smells Like Teen Spirit is the #1 most iconic song among Dell Inspirons.

The 50 most iconic songs, according to a computer

1. “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Nirvana

2. “Imagine,” John Lennon

3. “One,” U2

4. “Billie Jean,” Michael Jackson

5. “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Queen

6. “Hey Jude,” The Beatles

7. “Like A Rolling Stone,” Bob Dylan

8. “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction,” Rolling Stones

9. “God Save The Queen,” Sex Pistols

10. “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” Guns N’ Roses

11. “London Calling,” The Clash

12. “Waterloo Sunset,” The Kinks

13. “Hotel California,” The Eagles

14. “Your Song,” Elton John

15. “Stairway To Heaven,” Led Zeppelin

16. “The Twist,” Chubby Checker

17. “Live Forever,” Oasis

18. “I Will Always Love You,” Whitney Houston

19. “Life On Mars?” David Bowie

20. “Heartbreak Hotel,” Elvis Presley

21. “Over The Rainbow,” Judy Garland

22. “What’s Goin’ On,” Marvin Gaye

23. “Born To Run,” Bruce Springsteen

24. “Be My Baby,” The Ronettes

25. “Creep,” Radiohead

26. “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” Simon & Garfunkel

27. “Respect,” Aretha Franklin

28. “Family Affair,” Sly And The Family Stone

29. “Dancing Queen,” ABBA

30. “Good Vibrations,” The Beach Boys

31. “Purple Haze,” Jimi Hendrix

32. “Yesterday,” The Beatles

33. “Jonny B Goode,” Chuck Berry

34. “No Woman No Cry,” Bob Marley

35. “Hallelujah,” Jeff Buckley

36. “Every Breath You Take,” The Police

37. “A Day In The Life,” The Beatles

38. “Stand By Me,” Ben E King

39. “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag,” James Brown

40. “Gimme Shelter,” The Rolling Stones

41. “What’d I Say,” Ray Charles

42. “Sultans Of Swing,” Dire Straits

43. “God Only Knows,” The Beach Boys

44. “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” The Righteous Brothers

45. “My Generation,” The Who

46. “Dancing In The Street,” Martha Reeves and the Vandellas

47. “When Doves Cry,” Prince

48. “A Change Is Gonna Come,” Sam Cooke

49. “River Deep Mountain High,” Ike and Tina Turner

50. “Best Of My Love,” The Emotions

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!