The Most Hopeful Music in the World

- May 11, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In Mind Blown

0

0

It’s hard to know when to broach the subject of mid-20th century radical modernist composers with your kids. My daughter was sitting quietly at age six when I decided it was time.

“You’re performing a piece of music, you know.”

She looked up at me with the tired patience of a child of mine. I said a man named John Cage wrote a piece of music that was nothing but four minutes and 33 seconds of silence. She was playing it perfectly.

She thought for a second, then nodded. Then I told her about another piece by Cage — and this one so captured her imagination that she still mentions it ten years later.

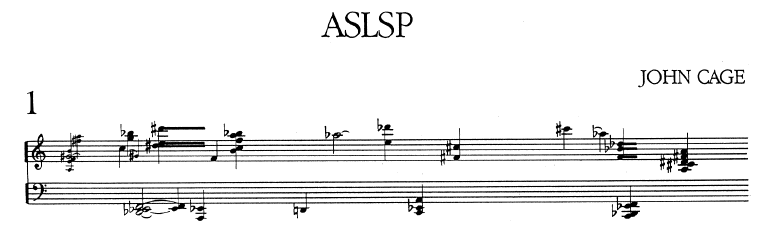

As Slow as Possible is a piece for organ. It usually runs 20-70 minutes, depending on how seriously you take the title. But if you take it literally, it raises a real question: how slow IS as slow as possible?

A group of musicians and philosophers discussed that at a conference after his death, deciding in the end that the determining factor would be how long it would take before the instrument it was played on fell apart. The oldest installed pipe organ in Europe at the time was 639 years old and about to give up the ghost.

“So they decided to play it really slow — so slow that it would last for 639 years,” I said. “They found an empty church in Germany and built a little organ. It started playing on September 5th, 2001. But the music starts with a rest – a silence – so the first thing they heard was nothing. For seventeen months!”

“Haha!” she said. “That’s weird.”

“And right in the middle of that silence—you were born.”

She thought about it, then whispered: “Awesome.”

“Then one day, when you were one year old, the first note started to play. Hundreds of people came to the church to hear it. Most of the time it’s playing with no one there. Little weights hold down the keys. Then every couple of years, it’s time for the note to change, and people come from around the world to hear that.”

“And it’s playing now?”

“Yeah, it’s playing right now. And here’s the thing: It’ll be playing on the moment you graduate from high school. It’ll be playing when you get your first job, when you get married, and when your kids are born. The music that started the year you were born will still be playing at the end of your life. It will be playing when your grandchildren are born and when they die, and their grandchildren, and on and on for 639 years.”

This project will strike some people as silly. There was a time it would have hit me that way. But the more I think about the longest piece of music, the more it moves me.

The organ in Halberstadt currently playing ASLSP by John Cage.

Suppose someone had started playing a piece of music in Halberstadt 639 years ago, in 1379. Only a generation had passed since the Black Death slew a third of Europe. The music would have ushered in the Renaissance, the voyages of the New World explorers, and the Scientific Revolution.

The religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries would have raged around it. It would have been playing as Halberstadt changed hands from Prussia to Napoleon’s Westphalia and back to Prussia before becoming part of Saxony, then Germany, playing as Allied bombs fell in 1945, as the town was closed into communist East Germany and as it was returned to the heart of a reunified Germany.

Would that piece have reached the last note?

Starting a piece of music implies an intention to finish it, so starting a 639-year long piece is an extraordinary act of optimism. It implies that we might still be here in 639 years, and that the intervening generations, with all of their own concerns and values and ordeals, will pick up the baton and run with the project we had begun, marking their calendars to visit the church and shift the weights when the time arrives.

I don’t care what the music sounds like, by the way. It’s the idea that moves me, makes me think. To hear the notes currently being played is to connect yourself to the recent past and the distant future.

So long as we can keep from killing each other, cooking the planet, or blowing up Halberstadt with technologies still undreamt, then maybe our optimism will have been justified. The hopeful music will finish.

Meanwhile, every few years for the rest of my life, she and I will both think about this little organ playing in a church in Germany.

The current chord:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SVPHOD3hN84″ parameters=”start=8″ /]

The Cage interview

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pcHnL7aS64Y” parameters=”end=59″/]

Follow Dale on Facebook:

The Greatest Mashup Ever: Why it Works

I love transformation, taking an existing thing and making something new out of it. It doesn’t always work. Sometimes it adds nothing to the original, and sometimes it’s a freakish horror that should never have seen the light of day.

But when it works, it can be gorgeous. Earth Wind and Fire’s “Got to Get You Into My Life.” Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations. Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven.

Mashups take it to another level as two or more existing songs are slammed together. And again, the results vary from terrible to pointless to good to THE GREATEST THING I HAVE EVER EXPERIENCED EVER OMG.

Let’s look at that one.

The Greatest Mashup Ever Created, End of Conversation™ brings two hideously different songs together: Taylor Swift’s caffeinated pop-tart “Shake It Off,” and the gothic shadow-world of “The Perfect Drug” by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails.

First the originals. For maximum appreciation of the mash, I suggest watching both of them first, but I am not the boss of you.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/nfWlot6h_JM” /]

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/sSLqeZzTU8I” /]

And now…Taylor Swift vs. Nine Inch Nails, by mashup artist Isosine.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/DhvXST1Rc3g” /]

Why It Works

The Lucky Coincidence

The two originals are not only close in tempo and key, but “Drug” is both a little slower than “Shake” (150 vs. 160 beats per minute) and a little lower in key (F major vs. G major). So by slightly speeding up “Drug” and slightly slowing down “Shake,” he brings both tempo and pitch into sync. The mashup is right smack in the middle of the two, 155 bpm and F# major. If they were further apart in pitch or tempo, at least one of the originals would have to be sped up or slowed down too far to work as well.

The New Story

The most common comment on the mashup is, “This shouldn’t work, but somehow it does.” There is no somehow. The opposition is a big part of why it works. There’s nothing new about contrasting light and dark, happy and grim. But this mashup combines the moods and themes of the two songs to create a third scenario. “Perfect Drug” is about an unnamed second-person obsession — You are the perfect drug. In the mashup, Swift becomes the “you,” the subject. The resulting narrative is instantly recognizable: She is the pretty, popular girl, the center of a cloud of beautiful people who move and dress and exist effortlessly at the top of the social pyramid. He’s the brooding obsessive loner, his attention fixed solely on her. She sings and dances, oblivious to his fixation, and his frustration grows.

At one point (1:15) she maddeningly seems to dance to his music as he sings The arrow goes straight to my heart/Without you everything just falls apart. At another, Swift’s trademark look of shocked surprise (1:37) is no longer about the row of jiggling butts behind her, but about his repeated line, And I want you. And yes, in this narrative, the icicle-dagger at 1:44 is especially creepy.

(As an antidote, there’s a nice comic touch when she sings “the fella over there with the hella good hair” (2:40) and it flashes to a greasy, glum Reznor.)

The Music

“Perfect Drug” is conveniently non-tonal for long stretches — it doesn’t get a tonal center at all for the first 50 seconds as he chants lyrics tunelessly against that cool, unsettling microtonal string thing. That allows Isosine to lay it over the Swift without worrying about pitch for about the first minute.

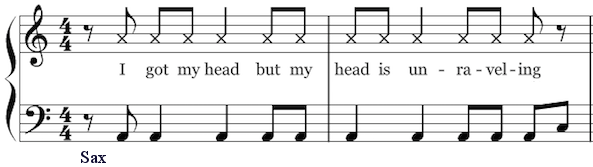

But they connect in other ways. Compare the rhythm in Reznor’s lyric to the rhythm in Swift’s bari sax (7 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/DhvXST1Rc3g” parameters=”start=06 end=13″ /]

For the first 30 seconds of the mash, those two insanely well-matched rhythmic motives knit the two songs together musically, sounding as if they were made to be together.

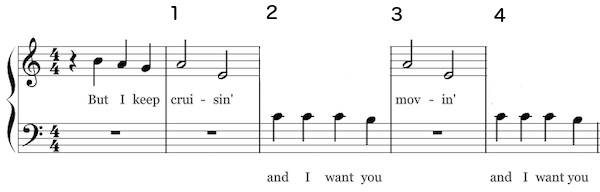

With a slight nudge of the fader, Isosine creates another jigsaw fit in the next 12 seconds: Swift’s melody lays in the first and third bars of each phrase, while Reznor’s lyrics are in the second and fourth bars, reiterating his obsession four times with increasing intensity (13 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/DhvXST1Rc3g” parameters=”start=30 end=44″ /]

And when “Perfect Drug” finally does go tonal in the refrain You are the perfect drug, the perfect drug, it works seamlessly with the bass and harmony of the Swift.

There’s more — there’s always more — but I’ll turn it over to you.

Trivia Bonus: The music videos for “Perfect Drug” and “Shake It Off” were (oddly) both directed by the same guy — filmmaker Mark Romanek.

Thanks to Paul Fidalgo, who first brought this mashup to my attention on his excellent blog iMortal.