labels

[continued from the open shelf]

“What does ‘humanist’ mean?” Delaney asked.

I swallowed. You’d think that, given my current work, I’d have sat myself down at some point and worked out guidelines for such inevitable moments:

CONTINGENCY 113.e

Requests for Definitions

iii. Term: “humanist”

Subset 2: Age 5-6

Children in this demographic cohort who make a direct request for the definition of “humanist” and/or any of its etymological class members (e.g. humanism, humanistic) are to be referred to Article 6, section D of the Humanist Manifesto, except in Arkansas and Hawaii.

Lacking such a road map, I simply answered her question. In retrospect, to my surprise, I even answered it correctly.

“A humanist is somebody who thinks that people should all take care of each other, and that even if there is a heaven or a god, we should spend our time making this life and this world better.”

“Awesome!”

I should note that Laney (age 6) uses Awesome! to signify everything from “I find that rather astonishing” to “That’s something I didn’t know before, and now I know it!” The latter meaning was in play here, I think, the word Awesome! signifying a new piece of the world clattering against the bottom of the piggy bank of her receptive mind.

Later that evening, after she’d been read to and sung to and tucked and kissed, I went back to my study to close up for the night. Scattered on and around the recliner she’d been sitting in were The Humanist Anthology, Tristram Shandy, The Kids’ Book of Questions, The World Almanac, The Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, The Simpsons and Philosophy, Cosmos, and Bulfinch’s Mythology. I reloaded the shelves and went to bed.

One week later, during our afterschool snack-chat, Laney informed me excitedly that there are nine different religions in her class.

“Nine, wow! How do you know there are nine?”

“We’re talking about different religions, and Mr. Monroe asked if anybody wanted to say what kind of religion their family believed.”

I was not surprised to hear of some diversity. There are lots of South Asian kids in the class. Compared to the demographic mayonnaise I had pictured North Atlanta to be, I’ve been thrilled with the diversity here. “And there were nine different ones?!”

“Yeah, nine…” She looked at the ceiling and began to rattle them off. “Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Baptiss, Jewish, Chains…” (“Chains” is probably “Jain,” one of the most benign and respectable religious traditions on Earth). She counted on her fingers. “Anyway, I can’t remember all of them.” She suddenly beamed. “And I was the only humanist!”

I paused for a week or so.

I am adamantly opposed to labeling children, or even allowing them to label themselves, with words that imply the informed selection of a complex worldview. Dawkins hits it right on the head when he refers to a long-ago caption on a photo in The Guardian. The photo was of three children in a Nativity play:

They are referred to as “Mandeep, a Sikh child; Aakifah, a Muslim child; and Sarah, a Christian child” — and no one bats an eye. Just imagine if the caption had read “Mandeep, a Monetarist; Aakifah, a Keynesian; and Sarah, a Marxist.” Ridiculous! Yet not one bit less ridiculous than the other.

That incisive analogy is Richard’s greatest contribution to secular parenting. I completely agree, as (I am increasingly convinced) do most nonreligious parents. Once a label is attached, thinking is necessarily colored and shaped by that label. I don’t want my kids to have to think their way out from under a presumptive claim placed on them by one worldview or another. So prior to age twelve, I won’t allow my children to be called “atheists” any more than I’d allow them to be called “Christians”–not even by themselves. (More on the ‘age twelve’ comment in a later post. Remind me when I forget.)

So my first impulse was to give the usual cautionary speech: Now be careful not to stop thinking. There are still too many questions to ask, too much you don’t know. Someday you’ll be able to make up your own mind on this, but it’s not time yet.

I looked at Laney, still beaming proudly through a mouthful of Nilla Wafers. At the time she had learned the meaning of humanist from me, I didn’t know she had said to herself, That’s me. She was obviously delighted to have had something to say when all the other kids were claiming their tribal identities, and clearly had no idea of the dark chain reactions set off in the fundamentalist mind by the word “humanist.”

“So what did Mr. Monroe say?”

“He said that was cool!” And I’m sure he did. He’s a great guy. No evidence of dark chain reactions in him, nor in her classmates.

“And he asked what a humanist believes,” she continues.

“What’d you say?”

“I said a humanist believes the most important thing is to take care of each other and the world.”

If she had called herself a secular humanist, I would have protested. But what is there about believing ‘the most important thing is to take care of each other and the world’ that requires more time and thought and study? Is she impeding her thought process by declaring this — or is this a value, like honesty and empathy, upon which she can build her search for an identity? There are, after all, both religious humanists and secular humanists. Erasmus and Paine, two great heroes of mine, were among the former.

Humanism has no connection to atheism for her. The definition I gave her even included the option of believing in a god and being a humanist. By calling herself a humanist in the broadest terms, she hasn’t bought into complex metaphysics; she’s simply embraced a concept that even a six-year-old can sign on to. And in the process, she introduced her classmates, and her teacher, to a new idea, and associated it with her smiling, eager, proud little face.

So Laney’s done it again — she’s taken my armchair abstractions and turned them inside out, making me realize that not all worldview labels are ridiculous or harmful for kids. Some can even serve as catalysts for the next stage in a child’s process of finding her place in the world. And the next stage, and the next.

photo by Paula Porter

the open shelf

- January 24, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, myths, Parenting

23

23

Something, well…ambiguous…happened the other day. Actually it was ambiguous at first, but it got more biguous as I thought about it. (Step away from the dictionary.) I wasn’t at all sure what to think about it at first. In the end, I decided it was…good. Really good, in fact.

But before I write about that, I have some setup to do. There are at least two stories embedded in this one. I’ll start with the open shelf policy and hope I remember the point in the end.

Years ago, I recall my mother-in-law describing her father’s book-lined study. He was a Baptist minister, by all accounts a very good man. His daughter was awed by the rows upon rows of spines of books along the walls of that room. I could picture it immediately, the walls of books and the little girl.

It got me wondering how my own kids would remember the books in our house. We have just over a thousand of them — as I was painfully reminded when we moved — including many old beauties. While living in the UK in 2004, I visited 63 used bookstores and acquired 93 books (I know the stats only because I was keeping a diary for an article I was writing about the antiquarian bookstores of London).

The first one I found — the first one — was a beautifully rebound volume of David Hume’s History of England, a second edition from 1796, stuck in amongst murder mysteries in the open market under Waterloo Bridge. It was £10, about $18. (Scroll up to the top photo again — it’s on the top shelf near the middle, bright brown leatherette binding with gold lettering, just to the right of the little red Huxleys.) If that doesn’t addict a person to scouring the bookstores of London, nothing will.

I’d love nothing more than to bore you by listing the other 92 I found, but I see your cursor twitching toward the scroll bar. The point is that, largely as a result of this fetish of mine, books are all over the place in our house.

In the 1920s, newly-moneyed members of the American middle class signaled their rise out of the working class in a couple of ways. Step one was putting a piano in the parlor. A wide selection of sheet music with elaborate illustrations on their covers would sit on the music rack. Some of these pianos were even played. Most were not.

(I grew up in California next-door to a retired couple. In their living room was a highly-polished parlor grand piano. I often wondered if anyone played it. My question was answered when I realized the framed pictures that covered the piano were also lined up on the closed cover of the keyboard.)

The other way the climbers of the 20s would signal their newfound class (pronounced “cleeeass”) was by filling their bookshelves with the classics (“cleeeassics”) and keeping their tops well-dusted.

Though there are certainly books in our collection we’ll never get to — life, I’m told, ends — ours do get a workout. One message our kids are getting is that books are not for wallpaper, and not for establishing one’s cleeeass. They are invitations to walk around in someone else’s head. And I wanted to be sure my kids knew that invitation was addressed to them as well. So one day, shortly after my mother-in-law’s story, I was taking a book down from a shelf and saw Connor, then about eight, reading one of his own books nearby.

“Hey Con, come here a sec.” He did. I indicated the books on the bookshelves in our living room and asked whose books they were.

“Yours,” he said. “And Mom’s.”

I told him they were actually for our whole family, and that if he was ever curious about any of them, he could take any book off any shelf anytime he wanted and look at it. I showed him which books were old and showed him how to open those carefully, supporting the spine, never flattening the pages. For a couple of days he played along, then lost interest, which was fine. The idea was the thing: he knew that there was in principle no prohibited knowledge.

I told Erin the same thing when she reached that age, with the same result. But a few months ago, though she was only six, I had a hunch it was Delaney’s turn.

Sure enough, she leapt on it. I’ll come upstairs now and find her in the recliner in my study with a book in her lap, leafing through pages, sounding out words and looking for pictures. A few weeks ago it was Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, and she was gawking at the snake-festooned head of Medusa, dangling from the outstretched grasp of Perseus. “AWESOME!” she said. And it was.

I’ve found her looking through a leatherbound Bible in German from the 1880s, Stephen Jay Gould’s Full House, and an illustrated Decameron. But as often as not, I don’t know what she’s reading. My study is bisected by a freestanding bookcase. When I’m working at my desk, I can’t see the recliner on the other side, though I can often hear her turning pages, saying “Awesome!” under her breath or (most hilariously) reading entire sentences of Vonnegut aloud. But it’s hard to prepare yourself for the really big moments when they come. And they always do.

“Dad?” said the bookcase.

“Yeah sweetie,” I said without looking up from my desk.

“What does ‘humanist’ mean?”

endings

An animated video of a kiwi with a dream nabbed “Most Adorable” last year in the YouTube Awards, along with 14 million views to date. As you’ll see, there’s quite a bit more profound going on here than mere adorability:

My kids all loved it. Connor watched it again and again, sorting out the implications of and emotions around the kiwi’s decision.

This morning, Erin asked to see it again, and I got her on the appropriate YouTube page. She watched it once, then clicked on one of the video responses that popped up. Suddenly she was clapping and woohooing.

“What happened?” I asked.

“THE KIWI LIVES!” she exulted. “He doesn’t die at the end! He LIVES!!”

I walked to the computer, puzzled. She replayed what she had just watched. Somebody had done a 15-second remake of the ending:

Most interesting of all are the YouTube comments on that one — mostly irate, convinced (as I am) that this revised ending robs the original of its poignancy and power. I agree, of course, but I LOVE what is revealed in that revision about the human inability to accept, or even think about, death.

In addition to death itself, the original raises issues about the right to die, the consequences of free will, the power of the creative spirit, the dangerous beauty of singleminded dreams, and much more. It’s incredibly rich and provocative. If instead you prefer a dose of denial with your entertainments, the revision’s for you. Or, if you prefer no remaining remnant of redeeming features, there’s this even more vapid rewrite:

lick, flush, reverse

- January 17, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In Atlanta, My kids, myths

12

12

Snow in Georgia, and once again I’m introduced to a neat and weird kid-legend I never heard before.

The prediction was for ice, and unlike Minnesota, which closes schools only for asteroid strikes and plague — and even then only in combination — Atlanta, we’ve been told, shuts down completely for an inch of snow or a hint of ice. Sure enough, the stores were wiped clean of milk and bread yesterday as the threat of “ice pellets” and even snow loomed in the forecast.

Our kids were elated, of course — not only at the prospect of tangible, frolic-worthy winter, but the apparent likelihood that school would be closed today. And they came home with a deal-sealer they’d learned from the Atlantans: to guarantee snow, all the kids must lick a spoon and put it under their respective pillows, flush an ice cube down the toilet, and sleep with their PJs reversed. In case you wondered at the title.

Child licking wooden spoon

(a highly suspect interpretation

of the Spoon Doctrine)

Around 5 pm it began — first with tiny, intermittent flakes, then with big beauties. Over an inch fell and stuck, plenty enough to give the school bus companies the vapors and close things down. My Minnesota-bred brood was spinning and howling on the deck, open mouths to the sky.

At bedtime, spoons were licked, ice flushed, PJs reversed. The fix was in.

Our alarm went off at 6 to the sound of the news announcer’s voice. The temperature had edged above freezing just long enough to melt the roads. Only three districts were closed, all rural, none of them ours.

I imagine the scene all over Atlanta was much the same as in the bedroom of my girls, and not too different from what I imagine would be the case when a volcano erupts despite the virgin tossed in. Talk turned to recriminations and the search for unorthodoxies. Somebody somewhere didn’t lick the spoon first, or enough, or didn’t put it under the pillow, or put it face up instead of face down, or slept with their PJs heretically oriented. Or maybe she wasn’t a virgin, someone in the village grumbles.

Thirty minutes after the bus took the girls and their grumbling colleagues to school, the boy came downstairs. His PJs. Look at his PJs!

“Con,” I said, soberly.

“What.”

“You’ve heard, I guess.”

“Yes. It’s robbery.”

“I see your PJs are on right. I won’t even ask about the spoon.”

“Pfft.”

Anybody reading this in Atlanta, especially anyone with disappointed schoolkids: I’d appreciate it if you kept this between us. He’s a good boy, really he is. Just a bit wrongheaded.

the heartbreak of all-done

- January 09, 2008

- By Dale McGowan

- In death, My kids, Parenting, reviews

10

10

Last year a client asked me to look over a rhyming children’s book she’d written. It was cute as a bug, but something wasn’t quite right. I picked one page and read it over and over. At last it hit me: it had ambiguous feet.

As opposed to this…

Left foot, left foot, right foot, right.

Feet in the day

Feet in the night.

There’s only one way to read that — the way Dr. Seuss wanted you to. He was a master of metrical feet — repeating patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables — which opened up children’s literature in a way we take for granted now. He saved us from Dick and Jane. Seuss is so perfectly metered that you can’t say it wrong.

A federal judge inadvertently proved the point last September when he tried, and failed, to imitate Seuss in a ruling from the bench. The judge had received a hard-boiled egg in the mail from a prison inmate protesting his diet, then declined the inmate’s request for an injunction, as follows:

I do not like eggs in the file

I do not like them in any style.

I will not take them fried or boiled

I will not take them poached or broiled.

I will not take them soft or scrambled

Despite an argument well-rambled.No fan I am of the egg at hand.

Destroy that egg! Today! Today!

Today I say! Without delay!

He screws the pooch in the second line, inserting an extra syllable (“in”), then again in the transition from “scrambled” to “despite.” And the last stanza is pure embarrassment. Did this judge sleep through the day in law school when they covered iambic tetrameter?

The point! The point! The point! The point!

Could you, would you, like the point?

My youngest daughter is on a Seussian bender lately. We’ve been alternating The Lorax and Oh The Places You’ll Go! for weeks — two of his four greatest (the others are Horton Hears a Who and the Grinch. Spare me The Cat in the Hat.)

We were in the middle of Oh, The Places You’ll Go! last week:

You’ll look up and down streets. Look ’em over with care.

About some you will say, “I don’t choose to go there.”

With your head full of brains and your shoes full of feet,

you’re too smart to go down any not-so-good street.And you may not find any you’ll want to go down.

In that case, of course, you’ll head straight out of town.It’s opener there, in the wide open air.

Out there things can happen and frequently do

to people as brainy and footsy as you.

Erin (9): Is he still alive?

Dad: Who?

Erin: Dr. Seuss.

Dad: Oh. No, he died about fifteen years ago, I think. But he had a good long life first.

And when things start to happen,

don’t worry buy viagra pills online uk. Don’t stew.

Just go right along.

You’ll start happening too.OH! THE PLACES YOU’LL GO!

I suddenly became aware that Delaney (6) was very quietly sobbing.

Dad: Oh, sweetie, what’s the matter?

Delaney: Is anybody taking his place?

Dad: What do you mean, punkin?

Delaney: Is anybody taking Dr. Seuss’ place to write his books? (Begins a deep cry.) Because I love them so much, I don’t want him to be all-done!

I hugged her tightly and started giving every lame comfort I could muster — well, everything short of “I’m sure he’s in Heaven writing Revenge of the Lorax.”

I scanned the list of Seuss books on the back cover. “Hey, you know what?” I said. “We haven’t even read half of his books yet!”

Feeble, I know. So did she.

“But we will read them all!” she said. “And then there won’t be any more!” I had only moved the target, which didn’t solve the problem in the least.

In addition to “paleontologist, archaeologist, and marine biologist,” Laney wants to be a writer. I seized on this, telling her she could be the next Dr. Seuss. She liked that idea quite a bit, and we finished the book. The next day she was at work on a story called “What Do I Sound Like?” about a girl who didn’t know her own voice because she had never spoken.

My instinct whenever one of my kids cries — espcially that deep, sincere, wounded cry — is to get them happy again. This once entailed nothing more than putting something on my head — anything would do — at which point laughter would replace tears. It’s a bit harder once they’re older and, instead of skinned knees, they are saddened by the limitations imposed by mortality on the people they love.

But is “getting them happy again” the right goal?

I’m often asked in interviews how I help my children accept death without the afterlife. Accept it?! Hell, I don’t accept it! People who “accept” death tend to fly planes into buildings. To think that I can or even should blunt that sadness too much is a suspect idea. Yet too often, I try.

Death is immensely sad, even as it makes life more precious. It’s supposed to be. So I shouldn’t be too quick to put something on my head or dream up a consolation every time my kids encounter the sadness of mortality. Sometimes it’s good to let them think about what it means that Dr. Seuss is all-done, and to cry that deep, sincere, heartbreaking cry.

fearthought

I’m up to my eyebrows in background reading for the sequel to Parenting Beyond Belief (possible names: Still Parenting Beyond Belief; Parenting Beyonder Belief; and Parenting Beyond Belief: The Empire Strikes Back). Likely release date is around December ’08.

In addition to reading huge amounts of useful stuff, I’m doing a bit of reading on the other side of the fence: religious parenting books. Some are very good, like the work of Christian parenting author Dr. William Sears. Some are mixed, including (to my admitted surprise) James Dobson, who serves up some quite sound advice along with his nonsense. Then there’s complete lunacy and even unintentional self-parody, for which we turn to author and televangelist Joyce Meyer.

fearthought

Joyce Meyer

Here’s a passage from Meyer’s “Helping Your Kids Win the Battle in their Mind“:

Satan will look for your child’s weakest area and attack at that point. He will attempt to fill your child with worry, reasoning, fear, depression and discouraging negative thoughts.

Don’t laugh at what she’s placed between worry and fear in the devil’s toolkit unless you turn straight to tears. According to her website, Joyce Meyer (who lives, interestingly, about three miles from my parents) has television and radio programs in “over 200 countries” — a truly remarkable achievement on a planet with 195 countries. Slightly less amusing is the fact that she has sold over a million copies of a book for which this passage can serve as an encapsulation:

I once asked the Lord why so many people are confused and He said to me, ‘Tell them to stop trying to figure everything out, and they will stop being confused.’ I have found it to be absolutely true. Reasoning and confusion go together.

from Battlefield of the Mind, p. 99

Last year she issued a version of Battlefield of the Mind “For Teens,” which I’m reading at the moment.

You can tell it’s intended for teens because of the cool dripping paint on the front cover, and the use of words like “wanna” and “gonna” and phrases like “where your head is at” (which teenagers use all the time, along with “groovy” and “hang ten.” If nothing else, Joyce is clearly hep to the jive.) My favorite sentence: “If you’re like most teens, you’ve probably seen the movie The Karate Kid.” Karate Kid was released in 1984, several years before today’s teenagers were born.

Fewer giggles were forthcoming from passages like this:

I was totally confused about everything, and I didn’t know why. One thing that added to my confusion was too much reasoning.

That’s right: it comes back again and again in her advice, in millions of books and throughout her broadcasting empire. Don’t even start thinking. Most troubling of all is the desperate attempt to make kids fear their own thoughts, right at the age they are supposed to be challenging and questioning in order to become autonomous adults:

Ask yourself, continually, “WWJT?” [What Would Jesus Think?] Remember, if He wouldn’t think about something, you shouldn’t either….By keeping continual watch over your thoughts, you can ensure that no damaging enemy thoughts creep into your mind.

I will defend to the death her right to put these opinions out there, and the rights of her millions of devoted readers to read it and to think it is something other than sad, ignorant, unethical, fearful sheepmaking. I’m just all the more motivated to put out a message precisely opposed to Meyer’s fearthought, one that advocates building up critical thinking and moral judgment in tandem, then inviting ideas into your head without fear that one of them will somehow jump you when you’re not looking.

Now I just need a word for the opposite of fearthought. I’m sure one will occur to me.

Freethought

This excerpt from a post of mine last June (“Rubbernecking at Evil”) shows how different are the planets Joyce Meyer and I occupy — even beyond the number of countries. Compare the bolded passage below with Joyce Meyer’s advice:

About a year ago, [my daughter Erin, then 8] went through a brief period of self-recrimination, literally dissolving into tears at bedtime, but uncharacteristically unwilling to discuss it. The morning after one such nighttime session, we were lying on the trampoline together, looking at the sky, and I asked if she would tell me what was troubling her. “Did you do something you feel bad about, or hurt somebody’s feelings at school?” I asked. “There’s always a way to fix that, you know.”

“No,” she said. “It isn’t something I did.”

“Something somebody else did? Did somebody hurt your feelings?”

“No.” A long silence. I watched the clouds for awhile, knowing it would come.

At last she spoke. “It isn’t anything I did. It’s something…I thought.”

I turned to look at her. She was crying again.

“Something you thought? What is it, B?”

“I don’t want to say.”

“That’s OK, you don’t have to say. But what’s the problem with thinking this thing?”

“It’s more than one thing.” She looked at me with a worried forehead. “It’s bad thoughts. I think about saying things or doing things that are bad. Like…”

I waited.

“Like bad words. That’s one thing.”

“You want to say bad words?”

“NO!!” she said, horrified. “I don’t at ALL!! But I can’t get my brain to stop thinking about this word I heard somebody say at school. It’s a really nasty word and I don’t like it. But it keeps popping into my brain, no matter what I do, and it makes me feel really, really bad!!”

She cried harder, and I hugged her. “Listen to me, B. You are never bad just for thinking about something. Never.”

“What? But…If it’s bad to say a bad word, then it’s bad to think it!”

“But how can you decide whether it’s bad if you don’t even let yourself think it?”

She stopped crying in a single wet inhale, and furrowed her brow. “Then…It’s OK to think bad things?”

“Yes. It is. It’s fine. Erin, you can’t stop your brain from thinking – especially a huge brain like yours. And you’ll make yourself crazy if you even try.”

“That’s what I’m doing! I’m making myself crazy!”

“Well don’t. Listen to me now.” We went forehead to forehead. “It is never bad to think something. You have permission to think about everything in the world. What comes after thinking is deciding whether to keep that thought or to throw it away. That’s called your judgment. A lot of times it’s wrong to act on certain thoughts, but it is never, ever wrong to let yourself think them.” I pointed to her head. “That’s your courtroom in there, and you’re the judge.”

The next morning she woke up excitedly and gave me a high-speed hug. Once she had permission to think the bad word, she said, it just went away. She was genuinely relieved.

Imagine if instead I had saddled her with traditional ideas of mind-policing, the insane practice of paralyzing guilt for what you cannot control – your very thoughts. Instead, I taught her what freethought really means.

I’m more than a little proud of myself for managing to say the right thing. That’s always a minor miracle. I don’t blog about the three hundred or so times in-between that I say the wrong thing.

In the year since that day, Erin has several times mentioned that moment, sitting on the trampoline, as the single best thing I ever did for her. As with most such moments, I had no idea at the time that I was giving her anything beyond the moment itself. I just wanted her to stop crying, to stop beating up on herself. But in the process, it seems, I genuinely set her free.

santatheology

One of my essays in Parenting Beyond Belief (“The Ultimate Dry Run,” p. 87) argued that the Santa myth, in addition to being a hugely enjoyable and harmless fantasy, can serve as a dry run for thinking one’s way out of religious belief.

It’s hard to even consider the possibility that Santa isn’t real. Everyone seems to believe he is. As a kid, I heard his name in songs and stories and saw him in movies with very high production values. My mom and dad seemed to believe, batted down my doubts, told me he wanted me to be good and that he always knew if I wasn’t. And what wonderful gifts I received! Except when they were crappy, which I always figured was my fault somehow. All in all, despite the multiple incredible improbabilities involved in believing he was real, I believed – until the day I decided I cared enough about the truth to ask serious questions, at which point the whole façade fell to pieces. Fortunately the good things I had credited him with continued coming, but now I knew they came from the people around me, whom I could now properly thank.

Now go back and read that paragraph again, changing the ninth word from Santa to God.

Santa Claus, my secular friends, is the greatest gift a rational worldview ever had. Our culture has constructed a silly and temporary myth parallel to its silly and permanent one. They share a striking number of characteristics, yet the one is cast aside halfway through childhood.

I offer as further evidence the following conversation between my son Connor — 12 years old and well post-Santa — and his sister Delaney, six, whose Santa-belief Connor has apparently decided must be kept alive at all costs. The setting is Grandma’s house on Krismas Eve for the Opening of the Early Presents:

GRANDMA: Oh, look, here’s another one: “To Delaney, from Santa!”

DELANEY: EEEEEE, he he hee! (*rustle rustle*) Omigosh, new PJs!! With puppy dogs!!

GRANDMA: Now, if they don’t fit, we can exchange them. I have the receipt.

DELANEY, with accusing eyebrows: What do you mean, you have the receipt? How could you have the receipt?

GRANDMA: Oh, I mean…well, Santa leaves the receipts with the gifts.

DELANEY, eyebrows still deployed: Uh huh.

CONNOR: Laney, be careful. If you don’t believe in Santa even for one minute, you’ll get coal in your stocking.

DELANEY: I don’t think so.

CONNOR: Well, you better not doubt him anyway, just in case it’s true!

DELANEY: I think Santa would care more that I was good than if I believe in him.

Holy cow. Didja catch all that? The whole history of religious discourse in 15 seconds. Reread it, changing Santa to God and get coal in your stocking to burn in Hell. For the finishing touch, replace Connor with Blaise Pascal and Delaney with Voltaire.

(P.S. The boy and I had a small chat after this. We don’t ban much in our house, but thoughtstoppers are definitely out. The Doctrine of Coal is as verboten as any other idea designed to squash honest doubts.)

Elv(e)s Lives!

ERIN (9): No, they don’t.

DELANEY (6): Yes, they do!

ERIN: Laney, they don’t.

DELANEY: They do!

It was my girls in their bedroom on the first day of Christmas break, (damned) early in the morning, apparently engaged in Socratic discourse. Let’s listen in from the hall:

ERIN: They do not.

DELANEY: They do so.

ERIN: Laney, there’s no way they come alive.

DELANEY: I know they come alive, Erin!

I walked in.

DAD: Morning, burlies!

GIRLS: Hi Daddy.

DAD: What’s the topic?

ERIN: Laney thinks the elves really come alive.

DELANEY, pleadingly: They do! I know it!

I didn’t have to ask what elves they were on about. It’s apparently an extremely old or very new tradition here in Georgia — I’m new in town and wouldn’t know which. Kids buy little stuffed elves and place them somewhere at night before they go to sleep. In the morning, the elf, having come to life in the night, is somewhere new.

ERIN: How do you “know” it, Laney?

DELANEY: Because. I just do.

ERIN: What’s your evidence?

(Oooooooo, the old evidence gambit! This should be good.)

DELANEY: Because it moves!

ERIN: Couldn’t somebody have moved it? Like the Mom or Dad?

DELANEY: But [cousin] Melanie’s elf was up in the chandelier! Moms and Dads can’t reach that high.

ERIN: Oh, but the elf can climb that high?

(Pause.)

DELANEY: They fly.

ERIN: Oh jeez, Laney.

DELANEY: Plus all the kids on the bus believe they come alive! And all the kids in my class! (Looks at me, eyebrows raised.) That’s a lot of kids.

So how to handle a thing like this? I want to encourage both critical thinking and fantasy. Fortunately Erin wasn’t being snotty or rude. Her tone was relatively gentle. As a result, Laney was not getting overly upset by the inquiry – just mildly defensive.

Erin finally looked at me and said in a half-voice: “I don’t want to ruin her fun, but…”

“You’re both doing a great job,” I interrupted. “This is a really cool question and you’re trying to figure it out! You’re asking each other for reasons and giving your own reasons, then you try to think of what makes the most sense—I love that!”

They both beamed.

“The nice thing is that you don’t have to agree.” (Celebrate diversity and all that. Only the Monolith is to be feared.) “You listened to each other and hashed it out. Now you can think about it on your own and decide, and even change your mind a million times if you want.”

I say that last line all the time. The invitation to change your mind knowing you can freely change it back makes it less threatening to test out alternatives. If you don’t like a new hypothesis, go back to your first one. It’ll still be there. That permission makes for more flexible thinking.

I also try to make the point that no one else can change your mind for you. You should always find out what other people think, but you don’t have to worry that they will reach in and change your mind without your consent. It’s amazing how powerful that simple idea is. In the end, only you can throw that switch and change your mind, so wander on through the marketplace of ideas without fear.

So they let it go. Erin got practice at gentle persuasion, and a little critical seed was planted in Laney’s mind, along with the invitation to hang on to the fantasy as long as she damn well pleases. When her love affair with reality becomes so well-developed that knowing the truth is more important to her than thinking stuffed elves come to life, she’ll happily move on. But just as in other areas of belief involving dead things coming to life when no one is looking, I want her to make decisions under her own power.

So they let it go. Erin got practice at gentle persuasion, and a little critical seed was planted in Laney’s mind, along with the invitation to hang on to the fantasy as long as she damn well pleases. When her love affair with reality becomes so well-developed that knowing the truth is more important to her than thinking stuffed elves come to life, she’ll happily move on. But just as in other areas of belief involving dead things coming to life when no one is looking, I want her to make decisions under her own power.

branch-on-ground

Acacia tree at sunset, Laikipia Plateau, Kenya

DELANEY (6, after ten silent seconds staring at our bathroom scale): I wonder how people in places like Africa and India weigh themselves if they don’t have scales.

DAD: Hm. I never even thought about that. Any ideas?

(Five seconds pass.)

DELANEY: I know! They could sit on a long tree branch and see how far down it bends.

DAD (recombing his hair): Holy cow, Lane. That would totally work.

ERIN (9): And they could say, “‘I weigh branch-halfway-down. How about you?’ And the other guy says, ‘I ate too much. I weigh branch-on-ground.'”

(Laughter.)

DELANEY: Or they could put carvings on the tree trunk to see how far down it goes.

This kid slays me on a daily basis. She recognized a problem, proposed a workable solution, and refined it, all within sixty seconds. I’m pretty sure that my own scientific investigations at the age of six were limited to which nostril produced the best-tasting boogers.1

___________________________

1Left side, by a mile — though further research is necessary.

strange maps

- December 07, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, Parenting, reviews, wonder

7

7

Please cancel my appointments for the rest of the month, take the phone off the hook, and don’t expect another blog entry until spring. I have found the website of my dreams and am going to live there for awhile. Someone please pay my rent, feed my children and satisfy my wife until I return.

Maps absorb me like a…what’s something really absorbent…like a sponge-like thing. In England I pored over the incredible Ordnance Survey maps for hours at a time.

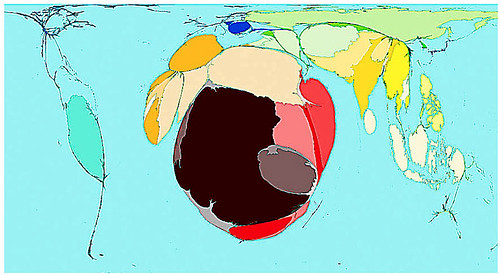

I’ve always particularly loved the paradigm rattlers, like this

which makes the point that a Northerly orientation is arbitrary, having been selected, by the most astonishing coincidence, by Northern Hemisphereans, who apparently like it on top.

I was 18 when I first saw Joel Garreau’s “Nine Nations of North America” concept, from the book of the same name:

Now I’ve found a blog called STRANGE MAPS, and I have no further need of the outside world. In addition to the above, there are maps to compare the relative wealth of nations today

and comparisons throughout time:

Deaths in war since 1945:

There is a map of US states renamed for countries with similar GDPs:

how the world would be if all the land were water and all the water land:

and what it’ll look like in 250 million years:

…all with intelligent commentary and links. I’ve only scratched the surface. There’s Europe if the Nazis had won. A map of the United States from the Japanese point of view. A map of the U.S. with the former territories of Indian nations overlaid. World transit systems drawn as a global world transit map in the style of the London Underground. A color-coded map of blondeness in Europe and of kissing habits in France.

Plop a child of a certain type and age (about 10-16) in front of Strange Maps (or another called Worldmapper, where the resized world maps originate) and don’t expect a response when you call ’em for dinner. I can’t wait for my boy to get home.