message from the future: the kids are all right

I’ve received quite a few lovely emails from secular parents thanking me for Parenting Beyond Belief. I LOVE these messages. They give me a ridiculously inflated sense of my own contribution to things. I always feel smart and handsome afterwards.

But a message today was particularly nice. It was from a secular kid, now all grown up. “My parents raised me without indoctrinating me into any faith,” she began. And they did so even though they themselves had been raised in orthodox religious homes.

My dad was willing to talk about his skepticism of religion with me in a very matter-of-fact way. I have memories of sitting at the kitchen table and having a conversation about how unlikely it was for Jesus to be the son of God and how much more likely it was that he was just a normal guy that people wanted to believe he was something more.

She went on to describe her earliest exposures to religion:

[My parents] gently encouraged me to explore different beliefs. Our family only went to church on Christmas and Easter (and that was really about keeping in touch with their cultural traditions), but it’s not so easy to ignore Christianity in the South. So, when I got a little older, they let me go to Sunday school when my friends invited me. I attended the Sunday schools of various Christian faiths like a mini-anthropologist: eager to learn, observant, and a bit detached from the whole thing.

This reminded me of a scene, not too long ago, in our own family. We were sitting in my mother-in-law’s Episcopal Easter service — high-church Episcopal, all gold iconography and slow processions with the Bible (of all things) held aloft.

I enjoy this immensely as theatre, as sociology, as a glimpse into a different expression of our shared human longings. But Connor was slouched low in the pew in clip-on tie and plastered hair, the perfect archetype of the miserable child in church.

I leaned over and whispered, “What if you had a chance to travel back to ancient Greece and watch a ritual in the temple of Zeus? What would you think about that?”

He smiled amazedly at the thought. “That would be so cool!”

“Well, just imagine you’re an anthropologist now, visiting from the future, where rituals have changed. There’s nothing quite like this anymore where you come from.”

He sat up wide-eyed and engaged the rest of the time.

Her message went on:

I knew I didn’t believe in God in elementary school (though, it didn’t stop me from exploring various belief systems when I got older, because, why not? I was willing to check them out). The majority of my friends that are non-believers were teenagers or young adults before they felt comfortable admitting their atheism and agnosticism. In addition, childhood beliefs are so hard to shake, that some of them still feel residual guilt over abandoning their faith and a fear of God’s retribution. I am forever grateful to my parents for–well, it’s kind of negative way of putting it, but I feel like, “Thanks mom and dad, for sparing me from religion.” I am able to go to an Orthodox church today, enjoy and respect it–the cultural traditions, the icons, the hypnotic nature of the rituals and the chanting–without being resentful of it or buying into all of the mythology.

I hope your book and website makes parents feel more comfortable with their decision to raise their kids without religion. Their kids will thank them later!

And that’s what this message felt like to me, like a note from my future kids as I hope and expect they will be: happy, bright, well-adjusted, free of resentments.

That lack of resentment in the second generation is a common pattern in many struggles for social transformation. Feminists have described the same thing with a mixture of amusement and pique. They resented the patriarchy and fought like hell so their daughters didn’t have to grow up butting their own heads against it. In return, they were accused by men and women alike of being too harsh, of being “obsessed with gender,” of pushing too hard and too fast. As a result of their efforts and sacrifices, their daughters now grow up never having known a time when women couldn’t fly planes, or vote, or wear jeans, or expect (if not always achieve) equal pay for equal work and an environment free of demeaning harassment.

Today, those daughters of the revolution — and believe me, I spent fifteen years teaching them — often roll their eyes at their mothers’ generation for making “such a big deal” out of gender issues. They can afford to roll those eyes, of course, because of the dragonslaying their mothers and grandmothers did.

My correspondent isn’t rolling her eyes, of course — but if thirty years down the road my kids are living in a country where a completely secular worldview is no big deal, then hey…I’ll gladly watch them roll their eyes as Dad sits in his recliner, ranting at the ottoman about this or that battle long since won for them.

carpe momento

There was a time when I was, shall we say, emotionally reserved. Not quite Spockish — maybe Alec Guinness in Bridge on the River Kwai. The music behind the menu selections on a DVD can bring Becca to tears, but until recently I could watch the scene in The Notebook where James Garner brings his wife out of her dementia just long enough to dance with her before she slips back under for another year — and never stop trying to remember the theme from The Rockford Files.

Those days are long gone. Parenting has made me a complete sap. A couple of weeks ago, Becca came back from Target and laid a couple of pretty pairs of socks on Laney’s and Erin’s pillows and a box of Connor’s favorite energy bars on his. “Just a little surprise,” she said. “They’ve been working so hard lately.”

I burst into tears.

This is me lately. The Notebook is entirely out of the question. I can’t even make it to the end of Charlotte’s Web.

I think I know what’s behind it. The winds of change are blowing hard around here lately. The youngest entered kindergarten, the middle is on the cusp of puberty, and the oldest — once a suckling babe — is 20 months from high school.

Becca and I (I realized last week with a shock) have reached the precise midpoint of our children’s childhood. Twelve years ago our eldest was born; twelve years from now, our youngest will enter college.

Erin, at age nine, is the emblem of all this, exactly midway between entering our home and leaving it. So it’s not surprising that a recent picture of Erin made me gasp:

Like all photos, it was a moment trapped in amber. But this particular moment had an absurdly large number of meaningful elements trapped in it — all of them in flux. Some had already changed in the weeks since it was taken. Everything else would change before you could sing “Sunrise, Sunset.”

Let’s take a quick inventory:

First the obvious. My little girl will shortly turn ten. Then eleven. Then twenty-six.

If she sticks with violin, the little blue tapes on the neck will come off soon. But she probably won’t even make it that far — she’s decided to switch back to piano, which means this photo narrows the frame to four possible months of her life, our first four months in Atlanta. Back on the dresser, beneath her bow, is her third grade league championship baskeball trophy from Minnesota (8-and-0, woohoo!). The design of the names on the wall is an idea from a dear family friend we left behind — Erin wanted her letters caddywompus, and Delaney wanted hers straight across.

Above Erin’s bed in the black frame is a collage of photos from her going-away party in Minnesota, signed by her friends. The Beatles poster has since given way to Zac Efron and Miley Cyrus.

At the head of her bed is an interesting blob of amber in its own right: a photo of Erin, Delaney, and Connor at Christmas in 2005. Will she still have a photo of her brother and sister over her bed in four years? It’s possible. I somehow doubt it.

I could go on with clothes, hair, Raggedy Ann, the paint on the walls, even her experiments with nail polish — but you get the idea. The shutter hadn’t even closed before these things started to change.

I could also work in some connection to meaning-making, or something about how the passage of time is especially poignant to those who know full well they are mortal. Mostly I just wanted to share a little of the intensely bittersweet feeling here at the midpoint of the most satisfying and purposeful period of my life.

the unconditional love of reality

…CONNOR AT THE WORLD OF COKE (…after the Tasting Room)

A Christian friend once asked me what it is about religion that most irritates me. It was big of her to ask, and I did my best to answer. I said something about religion so often actively standing in the way of things that are important to me — knowledge of human origins, for example, important medical advances, effective contraception, women’s rights…the simple ability to think without fear. I gave a pragmatic answer — and the wrong one.

Not that those things aren’t important. They’re all crowded up near the top of my list of motivators. But in the years since I gave that answer, I’ve realized there’s something much deeper, much more fundamentally galling and outrageous that religion too often represents for me — something that constitutes one of the main reasons I hope my kids remain unseduced by any brand of theism that endorses it.

What I want them to reject, most of all, is the conditional love of reality.

I’ve talked to countless Christians about their religious faith over the years. I have often been moved and challenged by what their expressed faith has done for them. But the doctrine of conditional love of reality simply mystifies, offends, and frankly infuriates me.

Conditional love is at play whenever a healthy, well-fed, well-educated person looks me in the eye and says, Without God, life would be hopeless, pointless, devoid of meaning and beauty. Conditional love is present whenever a believer expresses “sadness” for me or my kids, or wonders how on Earth any given nonbeliever drags herself through the bothersome task of existing.

Whenever I hear someone say, “I am happy because…” or “Life is only bearable if…”, I want to take a white riding glove, strike them across the face, and challenge them to a duel in the name of reality.

The universe is an astonishing, thrilling place to be. There’s no adequate way to express the good fortune of being conscious, even for a brief moment, in the midst of it. My amazement at the universe and gratitude for being awake in it is unconditional. I’m thrilled if there is a god, and I’m thrilled if there isn’t.

Unconscious nonexistence is our natural condition. Through most of the history of the universe, that’s where we’ll be. THIS is the freak moment, right now, the moment you’d remember for the next several billion years — if you could. You’re a bunch of very lucky stuff, and so am I. That we each get to live at all is so mind-blowingly improbable that we should never stop laughing and dancing and singing about it.

Richard Dawkins expressed this gorgeously in my favorite passage from my favorite of his books, Unweaving the Rainbow:

After sleeping through a hundred million centuries, we have finally opened our eyes on a sumptuous planet, sparkling with color, bountiful with life. Within decades we must close our eyes again. Isn’t it a noble, an enlightened way of spending our brief time in the sun, to work at understanding the universe and how we have come to wake up in it? This is how I answer when I am asked—as I am surprisingly often—why I bother to get up in the mornings.

I want my kids to feel that same unconditional love of being alive, conscious, and wondering. Like the passionate love of anything, an unconditional love of reality breeds a voracious hunger to experience it directly, to embrace it, whatever form it may take. Children with that exciting combination of love and hunger will not stand for anything that gets in the way of that clarity. If religious ideas seem to illuminate reality, kids with that combination will embrace those ideas. If instead such ideas seem to obscure reality, kids with that love and hunger will bat the damn things aside.

And when people ask, as they often do, whether I will be “okay with it” if my kids eventually choose a religious identity, my glib answer is “99 and three-quarters percent guaranteed!” That unlikely 1/4 percent covers the scenario in which they come home from college one day with the news that they’ve embraced a worldview that says they are wretched sinners in need of continual forgiveness, that hatred pleases God, that reason is the tool of Satan, and/or that life without X is an intolerable drag — and that they’d be raising my grandkids to see the world through the same hateful, fearful lens.

Woohoo! is not, I’m afraid, quite a manageable response for me in that scenario. Yes, it would be their decision, yes, I would still love their socks off — and no, I wouldn’t be “okay with it.” More than anything, I’d weep for the loss of their unconditional joie de vivre.

But since we’re raising them to be thoughtful, ethical, and unconditionally smitten with their own conscious existence, I’ll bet you a dollar that whatever worldview they ultimately align themselves with — religious or otherwise — will be a thoughtful, ethical, and unconditionally joyful one. Check back with me in 20 years, and for the fastest possible service, please form a line on the left and have your dollars ready.

finding nemo…belly up

- October 31, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In death, My kids

17

17

There’ve been three deaths in our immediate family in the past 48 hours. Wait, lemme go downstairs and check.

Okay, four.

Squishy, Squirmy, Stripey, and now–uh, another one–were found one at a time, white-eyed and motionless, in our new aquarium. They were tiger barbs. Now they’re not.

Yes yes, we took all appropriate steps in setting the thing up. I’ve had many aquaria in my life, enough to know precisely why these fish died: They died because fish are dying machines.

I tried to prepare the kids for this before we even walked out the door of Cheap Flushable Pets Warehouse. “I want you to know something,” I said. “Aquarium fish have a habit of dying. Often. And for no apparent reason. I just want you to be ready for that.”

But they were too busy cooing new names to the little terminal creatures through the walls of their plastic-bag ICUs to hear Daddy Cassandra moaning about the future.

“You’ll be my Squishy-wishy!” Erin cooed to her bag. “And you’re Stripey!”

The future arrived the next morning when I switched on the aquarium light and found Squishy stuck to the filter intake.

The girls feet were on the stairs. I panicked, grabbed the net, scooped the sushi, darted into the bathroom.

Flooooosh.

I emerged nonchalantly. “Morning girls!”

Erin looked at me suspiciously. “Why do you have that?”

I looked down at the net in my hand. “This?” I quickly realized that all possible cover stories for emerging from a bathroom with a dripping net are far worse than the truth. “Sweetie, I’m sorry, but one of your fish died during the night.”

“Which one?” She walked to the tank calmly and peered in. “Oh. Squishy is gone.”

“I’m sorry. Are you okay?”

“Yeah. It’s okay. I still have four.” It was a “5 for $5” deal on tiger barbs.

By the time she returned from school, another fish had swum the tunnel of light — another of her tigers.

By dinnertime, a third. “What the heck!” she said, mostly angry that the Fish Reaper was swinging his filleting scythe so selectively at her herd. Laney’s and Connor’s fish, all non-tigers, were still happily playing Who’s Behind the Bamboo, oblivious to the carnage around them.

“Can I touch it?” she said, staring at the sad little thing.

“Sure you can.” My kids’ ease with such things amazes me. Dead things have always called up a deep terror in me. And I’ve seen plenty: in addition to countless childhood pets, there was my father (aneurysm), grandfather (can’t recall), a restaurant patron (heart), a sheep in Scotland (drowned), and a man on a train platform in Vienna. I’ve always been shaken by the realization that such a thin line exists between life and death — that you are here, and then, often without warning, you are nowhere. The man in Vienna, like me, was preparing to board a train to Munich. Moments before, he probably had quite the same plans as mine. Instead, he cancelled every remaining appointment he had by crumpling to the platform, dead.

I scooped up Stripey and held the net out toward Erin. My nine-year-old self would have…well, he wouldn’t have asked to touch it in the first place. But if somehow he had, nine-year-old Dale would have poked it with one fingertip, then fled to the bathroom to scrub that fingertip raw. To get the death off. I hate dead things.

What I really hate, I think, is the reminder that one day I’ll end up Stuck To The Filter myself.

But Erin didn’t poke it and run. “Oh, Stripey,” she said as she picked it up with two fingers and laid it in her other palm. She stroked its side. “He’s so soft.” Laney joined her. Then Erin walked to the bathroom, said goodbye, and flushed.

I promised we’d pop on over to Aqua Hospice tomorrow. And if she points at another tiger barb, I’ll just reach into the tank, squish it, and hand the guy a buck.

waking up

- October 29, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In morality, My kids, Parenting, values

12

12

To be awake is to be alive. I have never met a man who was quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?

from Walden, Henry David Thoreau

I taught Chapter 2 of Walden in a freshman college seminar for years — then stopped teaching it for the last few. The students’ reaction to it depressed me. Eyes would roll, or wince, or slowly close in sleep. Though some were always reached and moved, most spent their time hating his admittedly ornate prose, ferreting out this or that hypocrisy, or answering his insights with a resounding “duh.”

I’d try to point out that worrying about the environment or about the restless expansion of unquiet civilization was far from duh-level obviousness in 1840s America. That these are now a bit more “obvious” is due in large part to cranky visionaries like Thoreau.

(Pfft. Why is it so easy to picture me, whitehaired, palsied, hands folded on a plaid lapblanket in my wheelchair, pathetically refighting old seminars with dim ghosts of eighteen-year-olds now on Medicare?)

I could go on about Thoreau — fired from teaching for refusing to use corporal punishment on his students, later jailed for refusing to support slavery and a particularly stupid war — but all of those flowed from the one thing that most grabbed me about him: he was trying as hard as he could to wake the hell up and to bring us along.

Which brings me to this alarm-clock photo:

It’s two million plastic beverage bottles, the number used in the US every five minutes.

Detail:

Closer detail:

IMAGES © CHRIS JORDAN. Used by permission.

The unreduced photo, by the way, is 5 feet high and 10 feet across. The impact in the gallery must be incredible.

The photographer is Chris Jordan, whose astonishing work draws attention to the consequences of runaway consumer culture. Take a minute to check out his website, and by all means, share it with the kids. Connor (12) was riveted, appalled, and motivated.

(Many thanks to Leslie’s Blog for introducing me to Chris’s work.)

from stereotype to tribute?

Two posts ago I mentioned that my daughter had chosen to dress as an American Indian for Hallowe’en. I was taken to task by a commenter for failing to think about the issues raised by such a choice.

I immediately saw her point and agreed with it. If my son had said he was dressing up as “a black person,” there’d be no question of allowing it. The fact that I knew Erin was doing it out of admiration (based on excellent recent curricula in her class) is beside the point: dressing up as a representative of an entire ethnic group — let alone an abstract collection of groups under a label like “American Indian” — is the very definition of stereotyping.

But now there’s been a very interesting development. Erin came to me last night, completely unprompted, and said, “I decided I’m not just an Indian anymore. I’m Sacagawea.” She was beaming.

Sacagawea. This seemed to instantly reframe the issue for me. Sacagawea — a historical person of great achievement — is a genuine hero to Erin right now. Whether or not it clears the issue entirely (I somehow doubt that), this does seem to move the gesture in the direction of tribute.

What do you think?

Erin as Sacagawea

“why does she always have to be ‘so beautiful’?!”

- October 24, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In diversity, My kids, myths, Parenting, values

17

17

HELEN OF TROY, looking (as usual) decidedly un-Greek

I like what’s happening to my nine-year-old middleborn, Erin B. And I don’t like what’s happening to me.

First of all: I know I’ve blogged a lot recently about bedtime myths and legends, and I don’t want to give the impression that my kids are on some force-fed diet of classic western civ. Every night I give them a choice of whatever they want to read. And for the last several weeks, the girls always yell, “Myth! Myth!” (To which I can only respond, “Yeth?”)

Last week it was Sir Gawain and the Green Knight — one of my favorite Arthurian legends, despite some admittedly strange bits. One reason I like it: I have a hunch that Gawain derives from Gowan, which is Gaelic for “blacksmith” and the root of our family name. Anyhoo, Gawain arrives in the Forest of Wirral, only days before his scheduled re-encounter with the Green Knight. Tired, he spots a nice castle and makes for it. The lord of the castle takes him in and gives him a great meal. Ahem:

After the meal was finished, the lord of the castle brought Gawain into a sitting room and sat him in a chair by a roaring fire. At last, the lady of the castle came to visit them. She was so very beautiful that she outshone even Queen Guinevere…

“Why does she always have to be ‘so beautiful’?!”

I blinked. It was Erin, her face scrunched into a frown. “Well…she doesn’t have to be, B. She just is.”

“But they always are! ALL the ladies in the myths are (in a mocking voice) ‘so beautiful’! Every one!”

Huh?? “They aren’t always…” My voice trailed off a bit in the manner of someone who realizes, too late, that he’s talking through his hat. Clearly she had noticed something I had not.

“Yes! They are! What about the one last night?” The night before we read Pyramus and Thisbe, the deep precursor to Romeo and Juliet. I reached up and pulled our condensed Age of Fable off the shelf and thumbed to the story.

First sentence:

Pyramus was the handsomest youth, and Thisbe the fairest maiden, in all Babylonia.

Hm. “Okay, so two in a row. But…”

“And Psyche!”

Hm. I flipped to Cupid and Psyche:

A certain king and queen had three daughters. Two were very common, but the beauty of the youngest was so wonderful that mere words…

Psyche Entering Cupid’s Garden

John William Waterhouse (c. 1904)

Huh. I began to search my mind, desperately, for a myth I had recently trotted before my girls in which a woman’s intelligence was praised, or her strength — something beyond her looks.

“Aha!” I said at last. “What about Atalanta? She was smart and faster than all the men!” I flipped to the page. “And her beauty wasn’t part of the story. Here: ‘Atalanta was a maiden whose face was boyish for a girl, yet too girlish for a boy.’ See?”

“Keep reading,” she said. “I remember.”

Sure enough, in the next paragraph, Atalanta, in a footrace, “darted forward, and as she ran, she looked more beautiful than ever.”

______________________

“I began to search my mind, desperately,

for a myth I had recently trotted before my girls

in which a woman’s intelligence was praised, or her strength —

something beyond her looks.”

______________________

No use going back one more night, I knew. That was the night we read about the Trojan War — starring Helen of Troy, “the most beautiful woman in all the known world.”

Holy crap!

I was about to bring up Medusa, but she’s the exception that proves the rule. According to Ovid, she was once beautiful, until she seduced Poseidon, and jealous Athena turned her into a hideous snake-haired beast. Again, looks are at the center of things.

One of the most interesting things about Erin’s exasperation is that (even by the testimony of non-parentals) she is a beautiful girl. Yet she can see that reducing a person to a single surface attribute is insulting, limiting, even when she herself has that attribute in spades. When she was not even three years old, we did a great little routine for friends and family. I’d say “Erin is beautiful and smart,” to which she would reply, without missing a beat, “An unnnnbeatable combo!”

I was proud of her for recognizing the anti-feminist vein in the old stories–and ashamed of myself for going numb to it. Why did I need my nine-year-old to remind me? There was a time when objectifying references to women made me howl. Fifteen years teaching at a women’s college will do that for you. Sure, I went to Berkeley, but it took a Catholic women’s college (yes, the irony drips) to thoroughly wake me up, to make me a feminist. I know that if I’m not outraged, I’m not paying attention. I know that.

Three days ago, I did it again. Erin walked into the kitchen wearing a fantastic American Indian costume Becca had just whipped up for Hallowe’en. So what did NeanderDad say?

“Erin, look at you! Are you gonna be an Indian princess?”

“No!” she said hotly.

“Uh…Indian maiden?”

“No!!”

“Uh…uh…a squaw?”

That’s right: I said SQUAW! I said SQUAW! Holy crap!

“DADDY!!!”

“Uh…you’re a…you’re a warrior!”

“THANK you!”

Okay. The nonviolence advocate in me winced, but the feminist in me stood tall. Almost as tall as my nine-year-old daughter.

and then we played

I’ve sprinted upstairs to transcribe the following dinnertable conversation with my daughter Delaney, nearly six. The names have been changed to etc:

DELANEY: I was at Kaylee’s house today after school, and she said she believes in God, and she asked if I believe in God, and I said no, I don’t believe in God, and her face got all like this

and she said, But you HAVE to believe in God!

DAD [w/mouthful of grilled pork]: Mmphh fmmp?

DELANEY: And I said no you don’t, every person can believe their own way, and she said no, my Mom and Dad said you HAVE to believe in God! And I said well I don’t, and she said you HAVE to, and I said that doesn’t make sense, because you can’t like go inside somebody’s brain and MAKE them believe something if they don’t believe it, and she said do your Mom and Dad believe in God, and I said no, they don’t believe in God either, and her face did like this again

and she ran into her room and got a book.

DAD [mashed potatoes]: Mm bhhk?

DELANEY: Yes, a picture book, and she said you HAVE to show this to your Mom and Dad, it’ll make them believe in God!

DAD: Whu…

DELANEY: And I said, I don’t have to show them that book, and she said if you don’t show it to them and if you don’t believe in God, you can’t come to my house anymore!

[Mom and Dad’s eyes meet, eyebrows fully deployed.]

MOM [who (having been raised right) swallowed her potatoes first]: Then what did you say, sweetie?

DELANEY: She kept saying it, so I cried. And then I said my dad says its okay for people to believe different things, and you can even change your mind a hundred times! And she said okay, okay, stop crying, you can come to my house anyway.

MOM: And then what?

DELANEY: And then we played.

spare the rod (and spare me the rest)

[Originally appeared as “Reason vs. the Rod” in the Institute for Humanist Studies Parenting Pages’ Parenting Beyond Belief column, Oct. 17, 2007.]

Nothing focuses the mind like scrutiny. I can get pretty flabby in my thinking when I’m just bouncing ideas against the inside of my skull like Steve McQueen’s baseball in The Great Escape. I’m always a genius in the solitary confinement of my head. But the moment I have to explain myself publicly, I put my ideas on a quick and painful diet.

Since the release of Parenting Beyond Belief, I’ve had to tone up my thoughts on parenting a bit. How can children be good without reference to a god, how can we explain death without heaven—these questions I can answer in my sleep. According to my wife, I often do.

More challenging are the essential questions. What is the essence of secular parenting? How is it fundamentally different from religious parenting? Those are the questions I love the most. They are instant liposuction for my head.

Secular parenting is not motivated primarily by disbelief in God. My religious doubts sprang from thinking for myself, not the other way around, so it’s freethought, not atheism, that’s down there at the root. When someone asks for the foundations of my parenting, I paraphrase the Bertrand Russell quote that begins my book: Good parenting is inspired by love and guided by knowledge. In other words, next to the love of my children, my parenting philosophy is motivated primarily by confidence in reason.

But I’ve wondered lately if my more practical parenting decisions aren’t rooted just as solidly in my confidence in reason. On reflection, they are indeed.

Take one example: I don’t spank my kids. This is interesting to me because religious fundamentalists spank in earnest, citing the biblical injunction “Spare the rod, spoil the child.”

There’s something doubly funny about the invocation of that scripture. Funny Thing #1 is that it isn’t scripture. Funny Thing #2 is its actual source—a bawdy poem by Samuel Butler intended to skewer the fundamentalists of his time, the English Puritans:

What med’cine else can cure the fits

Of lovers when they lose their wits?

Love is a boy by poets styl’d;

Then spare the rod, and spoil the child.

Samuel Butler, Hudibras, Part II (1664)

He’s lampooning the Puritan obsession with sexual abstinence as the cure for passion, using “the rod” in this case as a wickedly funny double entendre, and making sly reference to an actual passage from Proverbs: He that spares his rod hates his son: but he that loves him disciplines him promptly (Proverbs 13:24).

I never tire of hearing sex-averse fundamentalists quoting from a bawdy satire that was aimed at them—and invoking a penis in the bargain. It’s almost as much fun as watching my homophobic aunts happily shouting along with the refrain to “YMCA” as if it’s a song about recreation facilities. But as tempting as it is to refrain from spanking just because fundamentalists spank, I have a better reason. That’s right: confidence in reason.

Let me here confess that I have spanked my kids. It was seldom and long ago, before I had my parental wings. I’m still ashamed to admit it. Every time it represented a failure in my own parenting. Most of all, it demonstrated a twofold failure in my confidence in reason.

Every time a parent raises a hand to a child, that parent is saying you cannot be reasoned with. In the process, the child learns that force is an acceptable substitute for reason, and that Mom and Dad have more confidence in the former than in the latter.

I try to correct behaviors by asking them to recognize and name the problem themselves. Replace “Don’t pull the dog’s ears” with “Why might pulling the dog’s ears be a bad idea?” and you’ve required them to reason, not just to obey. Good practice.

“Every time a parent raises a hand to a child,

that parent is saying you cannot be reasoned with.

In the process, the child learns that force is an acceptable

substitute for reason, and that Mom and Dad have more

confidence in the former than in the latter.”

_______________________________

The second failure is equally damning. Spanking doesn’t work. In fact, it makes things worse. The research—a.k.a. “systematic reason”—is compelling. A meta-analysis of 88 corporal punishment studies compiled by Elizabeth Thompson Gershoff at Columbia University found that ten negative outcomes are strongly correlated with spanking, including a damaged parent-child relationship, increased antisocial and aggressive behaviors, and the increased likelihood that the spanked child will physically abuse her/his own children.

The study revealed just one positive correlation: immediate compliance. That’s all. So if you need your kids to behave in the moment but don’t care much about the rest of the moments in their lives—hey, don’t spare the rod!

Max Ernst, The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child

before Three Witnesses (1926)

Many people think a no-spanking policy is just plain soft on crime. And if spanking were the only way to achieve good behavior, I might just have to spank. I have very little tolerance for kids who are out of control, whether yours or mine. (Just so you know.) Fortunately, many other things get their attention equally well or better, without the nasty side effects. A discipline plan that is both inspired by love and guided by knowledge finds the most loving option that works. Spanking fails on both counts.

Instead, keep a mental list of your kids’ favorite privileges—staying up late, reading time before bed, Xbox, freedom, dessert, whatever. If they really are privileges rather than rights—don’t withhold rights—they can be made contingent on good behavior. Choose well, and the selective granting and withholding of privileges will work better than spanking. Given a choice between a quick spanking or early bedtime for a week—heck, my kids would surely hand me the rod and clench. Too bad—the quick fix is not an option.

The key to any discipline plan, of course, is follow-through. If kids learn that your threats are idle, all is lost.

I hope it’s obvious that all this negative reinforcement should be peppered—no, marinated, overwhelmed—with loving, affirmative, positive reinforcements. Catch them doing well and being good frequently enough, and the need for consequences will plummet. It stands to reason.

In the long run, if our ultimate goal is creating autonomous adults, we should not raise children who are merely disciplined but children who are self-disciplined. So if your parenting, like mine, is proudly grounded in reason, skip the spankings. We all have an investment in a future less saddled by aggression, abuse, and all the other antisocial maladies to which spanking is known to contribute. Reason with them first and foremost. Provide positive reinforcement. And when all that fails—and yes, it sometimes does—dip into the rich assortment of effective non-corporal consequences. Withhold privileges when necessary. Give time-outs, a focused expression of disapproval too often underrated.

And don’t forget the power of simply expressing your disappointment. Your approval means more to them than you may think.

_____________________

RESOURCES

Why Spanking Doesn’t Work (book)

Project NoSpank

For a look at the dark side, check out Darth Dobson’s take on spanking, including this immortal line: “[If spanking doesn’t seem to work,] the spanking may be too gentle. If it doesn’t hurt, it doesn’t motivate a child to avoid the consequence next time.”

.

.

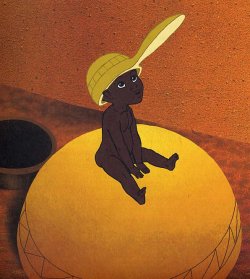

KID MOVIE REVIEW: Kirikou and the Sorceress

- October 15, 2007

- By Dale McGowan

- In My kids, myths, Parenting, reviews

9

9

A movie review for you this time — and oh my goodness, it’s hard to know where to start.

Desperate for something new for the kids, I happened on a film called Kirikou and the Sorceress in my Netflix recommendations. It had all the earmarks of a well-meaning flop, an animated parable based on African folktales — the kind of thing two Berkeley-educated bleeding-heart parents would make their kids sit through while eating Fair Trade seaweed crackers. But the viewer reviews were through the roof, so I took a shot.

And a flop, well-meaning or otherwise, it is not! Within three minutes we were all captivated by this surprising, funny, and uniquely moving animated film. A little boy walks out of the womb of his Senegalese mother, talking up a storm, and learns that the village into which he’s been born is under the thumb of the evil sorceress Karaba. His uncles have been eaten by the witch, and she has dried up the spring from which the villagers get their water.

[SPOILERS FOLLOW.]

His first question: Why is she so mean and evil? The adults are flummoxed by the very question: Does there have to be a reason?

As the adults alternately fight, cheat, and acquiesce to Karaba, Kirikou instead puts himself to the task of undoing the harm she’s done and of figuring her out. In the process, he learns that Karaba is the African equivalent of the man-behind-the-curtain — that most (not all) of her special effects have naturalistic explanations. She didn’t eat the men, for example, and a hidden animal is drinking up the water. He also learns that she is motivated by literal pain — a thorn — no, not in her paw, but in her spine.

The story also contains further evidence that the Christ story is only one version of a universal archetype, as little Kirikou sacrifices his own life to save the villagers — even those who rejected him — then is “resurrected.” And there is much rejoicing.

Also nice are the ways in which this hero paradigm does not parallel the classic western paragon. He is completely unpretentious, makes mistakes and cheerfully corrects them, changes his mind, and at one point, fatigued from his heroics, curls up in his grandfather’s lap for a rest.

Trust me on this one. 74 minutes. Ages 4-12.

[Pathetic sidenote:

The film’s content of natural nudity enraged some overseas distributors. Some requested airbrushing pants on the fully naked boys and men, as well as bras for the topless women. Michel Ocelot refused; this was African culture, and he wanted to stay faithful to it. In some countries, because of the distribution fights, it wasn’t released commercially until four years later.” (Wikipedia)

Allow me a moment to guess in which country most of this outrage was concentrated.]

Official website, including trailer

Netflix page

La version originale est en français!