How Music Does That – The Test Drive

Think you might like the HOW MUSIC DOES THAT podcast but struggle with commitment issues? I feel ya. Here’s a 7-minute sampler of episodes 1-5 to give you a taste.

Keep going. You know you want to.

Listen to “Ep 1: The Evolution of Cool” on Spreaker.

Listen to “Ep 2: The Strange DNA of a Surf Song” on Spreaker.

Listen to “Ep 3: When Truman Touches the Wall” on Spreaker.

Listen to “Ep 4: Let’s Get Sad with Galileo’s Dad” on Spreaker.

Episode 5 publishes on Sept 29.

Let’s Get Sad With Galileo’s Dad

A gorgeous technique to unify emotion in music has been passed down from the Renaissance to Radiohead. (17 min)

Listen to “Ep 4: Let’s Get Sad with Galileo’s Dad” on Spreaker.

Screwing with Darwin

Charles Darwin wrote a terrific book. Loved it the first time I read it, then read it twice more. And the more I read it, the more I liked it. Just super.

Not everyone feels the same about this book. Some were so disturbed by what he wrote that they cut whole passages out before its publication. Most people didn’t get to read the book in its complete and original form until 1958, when the excised passages were restored.

What? No no, not that Darwin book. I’m talking about his Autobiography.

Darwin sat down to write his autobiography in May 1876, “as if I were a dead man in another world looking back at my own life. Nor have I found this difficult,” he added, “for life is nearly over with me.” He apparently knew this from a line on the title page he had just written: Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Chills.

The idea to write a sketch of his life came from Julius Victor Carus, a zoologist in Leipzig who had translated the Origin into German and needed some bio-bits from Darwin for an encyclopedia entry. Ten years later, Darwin decided to write “recollections of the development of my mind and character,” driven in part by realizing “that it would have interested me greatly to have read even so short and dull a sketch of the mind of my grandfather [Erasmus Darwin] written by himself, and what he though and did and how he worked.”

He also said he thought the attempt at such a thing “would amuse me, and might possibly interest my children or their children.” Ironic, since it was one of his children who was to serve as the slicer-dicer of Charles’s recollections, and one of his children’s children who made it whole again.

The Autobiography first appeared publicly as part of Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, edited by his son Francis, a.k.a. Frank, and published in 1887.

Dear Frank is our villain in this tale, his father’s own Lord Braybrooke. But the more you learn about why Francis Darwin did what he did, the harder it is to fault him too thoroughly. Unlike Braybrooke’s flaying of Pepys’ Diary, Frank acted out of primary concern for the reputation of the author, his father, and the strongly expressed wishes of his mother Emma. Usually an author’s desires are plenty clear — he or she wrote the words he wanted included. But there was some disagreement about whether Darwin ever intended to publish his Autobiography, which does complicate the sorting of intent.

It got nasty. In the five years between Darwin’s death and the publication of the Autobiography, the Darwin family tore itself up over what should appear and not appear in the book. At one point, one wing of the family considered suing the other.

So Frank did his best. Then 71 years later, with the principals in the original fight all safely dead, his niece did better.

In its original unbuggered form, the Autobiography was a genuine page-turner, full of the kind of keen observation that made Darwin Darwin. Instead of the natural world, Darwin’s eye and mind are turned on himself and those around him, as well as the sometimes agonizing and deeply honest development of his own opinions. He says both flattering and unflattering things about people living and dead and expresses opinions both kosher and heretical.

In its buggered form, Darwin is an undiscerning dodderer. He likes everybody and everything just fine, especially those alive at the time of publication. (That’s right — in an interesting reversal, the dead are the only ones of whom Frank allows his dad to speak ill.) And the wonderfully complicated ebb and flow of his opinions on religion is reduced to a hazy, misleading mumble in favor of the status quo.

Fortunately for me, it was Nora’s edition that reached me first, which is probably why I read it more than once. But I wasn’t fully aware of its tortuous history until much more recently.

Portrait of a Book-Buggering

An incredible ability to pay attention may have been Darwin’s defining characteristic. This was the guy who found it possible to study barnacles for eight years straight. That superhuman ability to observe and notice was surely the reason he was able to figure out the puzzle of natural selection. And as a result of this well-honed ability, the original Autobiography is just bursting with sharp observations of the people around him.

An incredible ability to pay attention may have been Darwin’s defining characteristic. This was the guy who found it possible to study barnacles for eight years straight. That superhuman ability to observe and notice was surely the reason he was able to figure out the puzzle of natural selection. And as a result of this well-honed ability, the original Autobiography is just bursting with sharp observations of the people around him.

Sir Frank’s version? Eh, nassomush.

I’ll focus on four of my favorite passages from the original. First there’s Darwin on himself, a childhood memory:

About this time [age eight], or as I hope at a somewhat earlier age, I sometimes stole fruit for the sake of eating it; & one of my schemes was ingenious. The kitchen garden was kept locked in the evening, & was surrounded by a high wall, but by the aid of neighbouring trees I could easily get on the coping. I then fixed a long stick into the hole at the bottom of a rather large flower-pot, & by dragging this upwards pulled off peaches & plums, which fell into the pot & the prizes were thus secured. When a very little boy I remember stealing apples from the orchard, for the sake of giving them away to some boys & young men who lived in a cottage not far off, but before I gave them the fruit I showed off how quickly I could run & it is wonderful that I did not perceive that the surprise & admiration which they expressed at my powers of running, was given for the sake of the apples. But I well remember that I was delighted at them declaring that they had never seen a boy run so fast!

That fun bit of Charlie candor was entirely cut, lest the world learn that he picked fruit that wasn’t his when he was eight.

He had this to say about Charles Lyell, one of his greatest influences:

Charles Lyell

On my return from the voyage of the Beagle, I explained to him my views on coral-reefs, which differed compared to his, and I was greatly surprised and encouraged by the vivid interest which he showed. On such occasions, while absorbed in thought, he would throw himself into the strangest attitudes, often resting his head on the seat of a chair, while standing up. His delight in science was ardent, and he felt the keenest interest in the future progress of mankind.

Frank removed the best part of that one – Lyell’s quirk with the chair. See how it reads without that:

On my return from the voyage of the Beagle, I explained to him my views on coral-reefs, which differed compared to his, and I was greatly surprised and encouraged by the vivid interest which he showed. His delight in science was ardent, and he felt the keenest interest in the future progress of mankind.

Zzzzzzzzzzzzngk.

In one long passage, Charles offers incisive character sketches of a half dozen colleagues and friends:

Robert Brown

[Scottish botanist Robert Brown] was capable of the most generous actions. When old, much out of health, and quite unfit for any exertion, he daily visited (as Hooker told me) an old man-servant, who lived at a distance (and whom he supported), and read aloud to him. This is enough to make up for any degree of scientific penuriousness or jealousy. He was rather given to sneering at anyone who wrote about what he did not fully understand: I remember praising Whewell’s History of the Inductive Sciences to him, and he answered, “Yes, I suppose that he has read the prefaces of very many books.”

Oh, snap!

Richard Owen

I often saw Owen, whilst living in London, and admired him greatly, but was never able to understand his character and never became intimate with him. After the publication of the Origin of Species he became my bitter enemy, not owing to any quarrel between us, but as far as I could judge out of jealousy at its success. Poor dear Falconer, who was a charming man, had a very bad opinion of him, being convinced that he was not only ambitious, very envious and arrogant, but untruthful and dishonest. His power of hatred was certainly unsurpassed. When in former days I used to defend Owen, Falconer often said, “You will find him out some day,” and so it has proved.

Joseph Hooker

At a somewhat later period I became very intimate with [botanist Joseph Dalton] Hooker, who has been one of my best friends throughout life. He is a delightfully pleasant companion & most kind-hearted. One can see at once that he is honourable to the back-bone. His intellect is very acute, & he has great power of generalisation. He is the most untirable worker that I have ever seen, & will sit the whole day working with the microscope, & be in the evening as fresh & pleasant as ever. He is in all ways very impulsive & somewhat peppery in temper; but the clouds pass away almost immediately. He once sent me an almost savage letter for a reason which will appear ludicrously small to an outsider, viz. because I maintained for a time the silly notion that our coal-plants had lived in shallow water in the sea. His indignation was all the greater because he could not pretend that he should ever have suspected that the Mangrove (and a few other marine plants which I named) had lived in the sea, if they had been found only in a fossil state. On another occasion he was almost equally indignant because I rejected with scorn the notion that a continent had formerly extended between Australia & S. America. I have known hardly any man more lovable than Hooker.

TH Huxley

A little later I became intimate with Huxley. His mind is as quick as a flash of lightning & as sharp as a razor. He is the best talker whom I have known. He never writes & never says anything flat. Given his conversation no one would suppose that he could cut up his opponents in so trenchant a manner as he can do & does do. He has been a most kind friend to me & would always take any trouble for me. He has been the mainstay in England of the principle of the gradual evolution of organic beings. Much splendid work as he has done in Zoology, he would have done far more, if his time had not been so largely consumed by official & literary work, & by his efforts to improve the education of the country.

He would allow me to say anything to him: many years ago I thought that it was a pity that he attacked so many scientific men, although I believe that he was right in each particular case, & I said so to him. He denied the charge indignantly, & I answered that I was very glad to hear that I was mistaken. We had been talking about his well-deserved attacks on Owen, so I said after a time, “How well you have exposed Ehrenberg’s blunders;” he agreed and added that it was necessary for science that such mistakes should be exposed. Again after a time, I added: “Poor Agassiz has fared ill under your hands.” Again I added another name, & now his bright eyes flashed on me, & he burst out laughing, anathematising me in some manner. He is a splendid man & has worked well for the good of mankind.

Sir John Herschel

I may here mention a few other eminent men whom I have occasionally seen, but I have little to say about them worth saying. I felt a high reverence for Sir J. Herschel & was delighted to dine with him at his charming house at the C[ape] of Good Hope & afterwards at his London house. I saw him, also, on a few other occasions. He never talked much, but every word which he uttered was worth listening to. He was very shy & he often had a distressed expression. Lady Caroline Bell, at whose house I dined at the C. of Good Hope, admired Herschel much, but said that he always came into a room as if he knew that his hands were dirty, & that he knew that his wife knew that they were dirty.

That priceless passage, including some of the best available portraits of these guys, was reduced by Frank Darwin to this yawny blob of paste:

[Robert Brown] was capable of the most generous actions. When old, much out of health, and quite unfit for any exertion, he daily visited (as Hooker told me) an old man-servant, who lived at a distance (and whom he supported), and read aloud to him. This is enough to make up for any degree of scientific penuriousness or jealousy.

I may here mention a few other eminent men whom I have occasionally seen, but I have little to say about them worth saying. I felt a high reverence for Sir J. Herschel & was delighted to dine with him at his charming house at the C[ape] of Good Hope & afterwards at his London house. I saw him, also, on a few other occasions. He never talked much, but every word which he uttered was worth listening to.

Gah!

Finally, a passage that captured the personality of two major figures of the time and illustrated one of the human foibles Darwin disliked most — the craving for status and glory:

Rev. Wm Buckland

All the leading geologists were more or less known by me, at the time when geology was advancing with triumphant steps. I liked most of them, with the exception of [geologist and minister The Very Rev. William] Buckland who though very good-humoured & good-natured seemed to me a vulgar & almost coarse man. He was incited more by a craving for notoriety, which sometimes made him act like a buffoon, than by a love of science. He was not, however, selfish in his desire for notoriety; for Lyell, when a very young man, consulted him about communicating a poor paper to the Geol. Soc. which had been sent him by a stranger, & Buckland answered — “You had better do so, for it will be headed, ‘Communicated by Charles Lyell’, & thus your name will be brought before the public.

The services rendered to geology by Murchison by his classification of the older formations cannot be over-estimated; but he did not possess a philosophical mind. He was very kind-hearted & would exert himself to the utmost to oblige anyone. The degree to which he valued rank was ludicrous, & he displayed this feeling & his vanity with the simplicity of a child. He related with the utmost glee to a large circle, including many mere acquaintances, in the rooms of the Geolog. Soc. how the Czar Nicholas, when in London, had patted him on the shoulder & had said, alluding to his geological work — “Mon ami, Russia is grateful to you,” & then Murchison added rubbing his hands together, “The best of it was that Prince Albert heard it all.” He announced one day to the Council of the Geolog. Soc. that his great work on the Silurian system was at last published; & he then looked at all who were present & said, “You will every one of you find your name in the Index,” as if this was the height of glory.

The whole passage was cut. Everything.

I could go on and on. Over two dozen passages like these were cut out of the Autobiography, draining much of the color and humanity out of Darwin’s self-portrait.

The reason we know what was cut is that granddaughter Nora Barlow painstakingly listed the formerly excised passages in the back of her 1958 edition, about which more shortly. I do understand Frank’s impulse, even though all of these people were dead at the time of publication except Huxley. But I am terribly grateful for Barlow’s work.

It wasn’t the character sketches that put the Darwins at each other’s throats, though. It was the question of whether Charles Darwin’s description of the development of his own religious doubt should see the light of day.

Hiding Darwin’s Religious Opinions

I had a passing knowledge of evolution in high school. Better than the average bear, but still sketchy. I majored in physical anthropology at Berkeley not for the dazzling job prospects but to fill in that sketch.

In addition to changing and deepening my understanding of what it means to be human, a fuller grasp of human evolution led me to wonder how traditional religion could in any significant way be made to fit with what we now know. (See earlier post.) And I remember wondering what Darwin thought about that.

He was seriously religious as a young man, even trained for ministry and annoyed his Beagle shipmates with fundamentalist pronouncements. If, after the Galapagos and the Origin and The Descent of Man, Darwin was still a conventionally religious man, I knew I must have really missed something. So I picked up Darwin’s Autobiography in my senior year to find out.

Nora Barlow

If I’d picked up the 1887 edition by his son Francis, published five years after Charles died and reissued many times since, I’d have been puzzled but chastened. He doesn’t get into religion much at all in that one, and when he does, he seems to mostly affirm his ongoing conventional beliefs. And I would almost certainly have never looked further.

Fortunately it was the 1958 edition by Charles’s granddaughter Nora that found me. As mentioned above, Nora restored the bits that the earlier edition had expunged under pressure from Charles’s wife Emma. Nora was able to do this because all of the family members who’d nearly come to blows over what to leave in and what to leave out were now demised.

If I’d read the first edition, I might have imagined a man with religious convictions essentially intact. Some side-by-side passages, with cut passages in red:

FIRST EDITION (1887)

I liked the thought of being a country clergyman. Accordingly I read with care Pearson on the Creed and a few other books on divinity; and as I did not then in the least doubt the strict and literal truth of every word in the Bible, I soon persuaded myself that our creed must be fully accepted.

RESTORED EDITION (1958)

I liked the thought of being a country clergyman. Accordingly I read with care Pearson on the Creed and a few other books on divinity; and as I did not then in the least doubt the strict and literal truth of every word in the Bible, I soon persuaded myself that our creed must be fully accepted. [It never struck me how illogical it was to say that I believed in what I could not understand and what is in fact unintelligible.]

A 12-page section titled “Religious Beliefs” underwent the most vigorous edits. The bracketed red text was omitted from the first edition:

During these two years I was led to think much about religion. Whilst on board the Beagle I was quite orthodox, and I remember being heartily laughed at by several of the officers (though themselves orthodox) for quoting the Bible as an unanswerable authority on some point of morality. I suppose it was the novelty of the argument that amused them. [But I had gradually come, by this time, to see that the Old Testament from its manifestly false history of the world, with the Tower of Babel, the rainbow at sign, etc., etc., and from its attributing to God the feelings of a revengeful tyrant, was no more to be trusted than the sacred books of the Hindoos, or the beliefs of any barbarian.]

It’s sometimes fascinating to see what Emma insisted be struck out and what she allowed in. She bracketed a portion of the following passage for deletion — the red below — but allowed the admission of disbelief in the first part:

I found it more and more difficult, with free scope given to my imagination, to invent evidence which would suffice to convince me. Thus disbelief crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete. The rate was so slow that I felt no distress [and have never since doubted for a single second that my conclusion was correct. I can indeed hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and this would include my Father, Brother and almost all of my friends, will be everlastingly punished. And this is a damnable doctrine.]

It’s not even his conclusion but the strength of his confidence that apparently unnerved his wife. As for the damnation, she wrote in the margin

I should dislike the passage in brackets to be published. It seems to me raw. Nothing can be said too severe upon the doctrine of everlasting punishment for disbelief–but very few now wd. call that ‘Christianity,’ (tho’ the words are there).

Tho’ the words are there. And 130 years later, the damnable words in the Bible are still there. Some books dodge the red pen more easily than others.

Francis oversaw an even more abbreviated 1892 American edition in which the entire 12 pages exploring Charles’s religious beliefs are replaced with a single bracketed fib:

[After speaking of his happy married life, and of his children, he continues:]

Jaysus. That Ninth Commandment is always the hardest.

Yet if you look hard enough, in all but the God-Bless-America edition, you can find one quiet sentence in which Darwin was allowed to clearly state his actual theological conclusions. Like Huxley, he utterly rejected belief in the claims and doctrines of Christianity, but said

The mystery of the beginning of all things is insoluble by us; and I for one must be content to remain an Agnostic.

The distortion of Darwin’s views continued for years. One of the most galling attempts was by Lady Elizabeth Hope, an evangelist who published a fabricated story in 1915 claiming to have heard Darwin renounce evolution and embrace Jesus on his deathbed. Francis redeemed his editorial self brilliantly. “Lady Hope’s account of my father’s views on religion is quite untrue. I have publicly accused her of falsehood, but have not seen any reply. My father’s agnostic point of view is given in my Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, Vol. I., pp. 304–317,” he wrote to a publisher in 1918. “I was present at his deathbed,” said Charles’s daughter Etty. “Lady Hope was not present during his last illness, or any illness. I believe he never even saw her, but in any case she had no influence over him in any department of thought or belief. He never recanted any of his scientific views, either then or earlier. We think the story of his conversion was fabricated in the U.S.A. …The whole story has no foundation what-so-ever.”

Etty’s niece Nora eventually put the pieces back together, but the genie never goes all the way back in. Several of the bestselling versions of Darwin’s Autobiography on Amazon are still the Francis Darwin edition.

Thanks for trying, Nora.

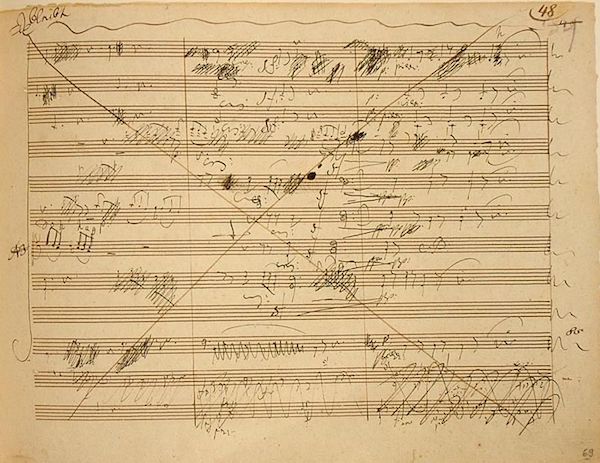

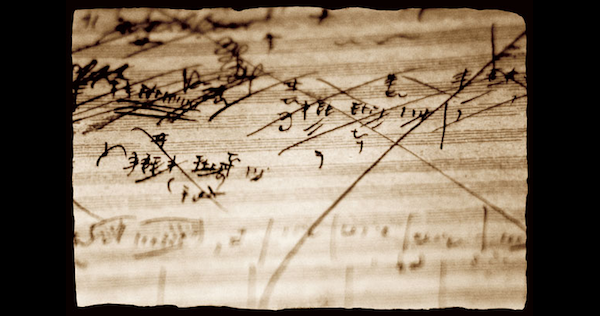

No, Beethoven Did Not Math His Way to Greatness

Beethoven’s sketchbook, 1815. Scheide Library. Princeton University. Photographed by Natasha D’Schommer from the book Biblio.

8 min

That Beethoven not only continued to Beethoven but composed his greatest works long after going profoundly deaf is entirely astonishing. Like many astonishing things, it spawned a cottage industry of explanations, most of which are moored in a misunderstanding of how composition works.

Ein Beispiel!

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zAxT0mRGuoY” /]

It’s seductive, this idea that the people we call geniuses in various fields do things in some fundamentally different way. Maybe it’s a way of forgiving ourselves for being non-geniuses, I don’t know. When it comes to explaining a deaf genius composer, the seduction is even greater. We are drawn toward anything that sounds remotely plausible.

The video above implies that Beethoven somehow used a knowledge of mathematical ratios and the physics of sound to compensate for his deafness and achieve greatness. The relationship between music and math and physics is fascinating, and I’ve written about it myself many times. But the implication that understanding the math of musical sound played any role in Beethoven’s ability to compose after going deaf in his thirties is (be nice!)…not true.

Any composer can write music in pin-drop silence, just as any writer of language can do. If I give you a line of poetry:

There once was a man from Nantucket

and ask you to compose the next line in your head, you can do it and write it down without hearing it spoken. The better poet you are, the better the result. You draw on a lifetime of experience with language and an acquired grasp of syntax and semantics, run through a number of options in your head, “hear” what you want mentally, then write it down. Then the process of improving it begins.

Music works much the same way. You write down the kernel of an idea, then realize it’s awful. So you improve it, little by little. If your ears work, you’ll check it at the piano and make adjustments. If they don’t, you play it in your head. This is not magic — after many years of practice and experience, I can do it myself. Beethoven just did it much, much better than I do. He didn’t use math.

One way we know that is from the thousands of pages of his extant sketchbooks.

Fascinating things, these sketches. He would start with a nugget of an idea — as often as not some inauspicious turd of a melodic fragment — then cross it out angrily and improve it on the next line, cross that out, improve, etc., until at the bottom of the page you have the fully-realized opening bars of the Pathétique Sonata.

You know what’s missing from the sketchbooks? Equations. In a very real way, the difference between Beethoven and the rest of us is how far down the page of the sketchbook you go before quietly saying “Nailed it” and getting lunch.

Beethoven had a lifetime of experience and an acquired grasp of the syntax and semantics of music, and he used that to create new compositions. What’s amazing is not that he composed after losing his hearing, but that he composed so skillfully without the advantage of testing aurally as he went. That really is hard, but not remotely impossible. Even more amazing is something too seldom mentioned — that Beethoven led a revolution in musical style, creating the Romantic period nearly singlehandedly while deaf. There’s no reason to believe that math, for all its inherent beauty, played any conscious part in that process.

The Power of Two: How Shared Dissent Can Make All the Difference

First published in 2011, this article feels especially urgent in 2018. Erin is now a junior in college.

A few days ago, Erin, my eighth-grader, made me proud. That alone is not news. But in this case she showed courage in someone else’s defense, and when that happens, my shirt buttons grab their crash helmets and wince.

“Guess what happened today,” she said.

I gave up.

“I was at the table in the cafeteria with these three other kids, and two of them asked the other girl where she went to church. She said ‘We don’t go to church,’ and their eyes got big, and the one guy leaned forward and said, ‘But you believe in God, right?'”

Oh here we go. I shifted in my seat.

“So the girl says, ‘Not really, no.’ And their eyes got all big, and they said, ‘Well what DO you believe in then??’ And she said, ‘I believe in the universe.’ And they said, ‘So you’re like an atheist?’ And she said ‘Yes, I guess I am.'”

I looked around for popcorn and a five-dollar Coke. Nothing. “Then what??”

“Then they turned to meee…and they said, ‘What about YOU? What do YOU believe?'” Another pause. “And I said, ‘Well…I’m an atheist too. An atheist and a humanist.'”

She’s 13, old enough to try on labels, as long as she keeps thinking. She knows that. And she’s recently decided that her current thoughts add up to an atheist and a humanist.

“And I looked at the other girl, and…like this wave of total relief comes over her face.”

Oh my word. What a thing that is.

“Erin that’s so great,” I said. “Imagine how she would have felt if you weren’t there!!”

“Yeah, I know!!”

I’ll tell you who else knows — Solomon Asch.

The Asch experiment is one of the great studies in conformity. When you are alone in a room full of people whose opinion differs from yours, the pressure to conform is enormous. But when individuals were tested separately without group consensus pressures, fewer than 1 percent made any errors at all. The lesson of Solomon Asch is that most people at least some of the time will defy the clear evidence of their own senses or reason to follow the herd.

One variation in the design of the study provides a profound lesson about dissent. This is the one that Erin’s situation reminded me of. And it’s a crucial bit of knowledge for any parent wishing to raise an independent thinker and courageous dissenter.

In this version, all but one of the researcher’s confederates would give the wrong answer. The presence of just one other person who saw the evidence in the same way the subject did reduced the error rates of subjects by 75 percent. This is a crucial realization: If a group is embarking on a bad course of action, a lone dissenter may turn it around by energizing ambivalent group members to join the dissent instead of following the crowd into disaster. Just one other person resisting the norm can help others with a minority opinion find their voices.

This plays out on stages even larger than the school cafeteria. On April 17, 1961, the US government sent 1,500 Cuban exiles to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. The idea was to give the US plausible deniability—barely plausible, but still. It was supposed to look like the exiles did it on their own.

Well, it did end up looking like that. The invasion was a mess of lousy planning and execution. Most of the 1,500 were killed or captured by a force of 20,000 Cuban soldiers, and the US government was forced to essentially pay a ransom of 53 million dollars for the release of the prisoners. And that’s in Mad Men dollars—it would be $510 million today. Cuba’s ties with the Soviet Union were strengthened, and the stage was set for the Cuban Missile Crisis six months later.

In short, it was a complete disaster. And in retrospect, that should have been obvious to those who planned it. But among President Kennedy’s senior advisers, the vote to go ahead had been unanimous. Why? It came out later that several of them had serious doubts beforehand but were unwilling to express those doubts since they thought everybody else was on board. It was the height of the Cold War, and nobody wanted to look “soft.” The climate of the discussions made real dissent too difficult to articulate, so a really bad idea went unchallenged.

The presidential historian Arthur Schlesinger was there for most of the discussions, and he later said that he was convinced that even one dissenter could have caused Kennedy to call off the invasion. ONE. He said he wished most of all that he had found the strength to be that dissenter.

At least Kennedy learned his lesson. During the Missile Crisis later that year, he made a point of fostering dissent and encouraging the collision of ideas among his advisers. The resulting policy led to the peaceful conclusion of what may have been the most dangerous crisis in human history (so far).

Many think that times of crisis and war are the worst possible times for argument and dissent. Hitler certainly thought so. He often said the mess of conflicting opinion in democracies would cause the Western powers to crumble before the single-minded focus of his military machine. He got the difference right but misdirected the praise. Military historians are pretty much agreed that the stifling of dissent in the Third Reich’s military decision-making was its fatal flaw. It was entirely top-down. Only if Hitler’s plans were flawless could that system be stronger than one in which ideas contend for supremacy.

So Montgomery and Patton’s pissing contests, MacArthur and Truman’s showdowns, and the constant whirl of debate among the Allies and even among the branches of the American service was a better approach to running a war than the single-minded dictates of dictators, from Napoleon to Hitler to Saddam Hussein. Crush dissent and you will most often end up shooting yourself in the foot. United We Stand is bad policy, even in wartime.

Dissent is often discouraged in the corporate world as well. Jeffrey Sonnenfeld’s research found that corporate boards that punish dissent and stress unity among their members are the most likely to wind up in bad business patterns. It’s corporations with highly contentious boards that tend to be successful. Not always—it depends on the nature of the contention—but when boards generate a wide range of viewpoints and tough questions are asked about the prevailing orthodoxy, they tend to make better decisions in the end. All ideas have to withstand a crossfire of challenge so the bad has a chance of being recognized and avoided.

A list of corporations with boards that valued conformity and punished dissent reads like a Who’s Who of corporate malfeasance: Tyco, WorldCom, Enron.

There’s something so counter-intuitive about all this. It seems on the face of it that uniting behind an idea or position or plan is the best way to ensure success. And it can be, if the idea or position or plan is good in the first place. And the best way to ensure that it is good is by fostering dissent from the beginning.

And “from the beginning” really means long before the meeting even begins — while the decision makers are still in the eighth grade cafeteria, learning to accept the presence of difference in their midst.

Had the other girl in my daughter’s story not mustered the courage to self-identify first as a person with a different perspective — in this case an atheist — Erin would have been statistically less likely to share her own non-majority view. Once the girl spoke up, Erin’s ability to join the dissent went up about 75 percent. And once Erin shared the same view, the other girl enjoyed a wave of retroactive relief at not being alone.

The other two kids also won a parting gift. They learned that the assumed default doesn’t always hold, and that the world still spins despite the presence of difference. They’re also likely to be less afraid and less astonished the next time they learn that someone doesn’t believe as they do, which can translate into greater tolerance of all kinds of difference.

Ep 3: When Truman Touches the Wall

From a Bach fugue to Diana’s funeral to Truman’s wall, this technique is the music of finality.

Listen to “Ep 3: When Truman Touches the Wall” on Spreaker.

A Bump in the Fence Line: One Step Further from Bigotry

I love finding out that a concept I’ve had in my head for years has a name.

Example: Someone dislikes all gays, then learns that his brother is gay. Instead of dropping the prejudice altogether, he will often grant an exception: “I don’t like gays, but Kevin’s okay.”

In American Grace, Putnam and Campbell call this the Aunt Susan principle. Even people in relatively homogeneous families and social groups often (and increasingly) have an Aunt Susan or a “pal Al” who is different from the rest — a Jew among Christians, gay among straights, atheist among believers — and still a good egg. Granting the exception can be a first step toward dismantling assumptions and stereotypes.

Multiple studies have shown that support for same-sex marriage is strongly linked to having close friends or family who are gay. It’s less a comprehensive change-of-heart than a willingness to accommodate someone in your own circle.

I learned from Dr. Brittany Shoots-Reinhard that social psychologists have an even better name for this kind of exception-making. It’s called re-fencing. Instead of tearing down the fence that separates us from a disliked or distrusted group, we build a little bump in the fence line to accommodate the one we know and love.

It’s not always a positive thing. Re-fencing can also be a way of resisting that bigger step, a form of “stereotype maintenance” rather than stereotype change.

But it can be a start. The key to helping someone move past this middle step, to encourage a more complete dismantling of the prejudice, Shoots-Reinhard says, is to “confront people with multiple instances of disconfirmation, like multiple friends coming out as atheist.”

In time, hopefully, the fence becomes too curvy to stand.

A Cricket in the Renaissance (Josquin – El Grillo)

High in the wall of the Sistine Chapel is a choir loft called the cantoria. Built in 1471, it was off limits to anyone but singers in the papal choir for 350 years. In the absence of adult supervision, centuries of singers carved their names in the wall. A member in the 1490s named Josquin des Prez (translation: Josquin of Prez) was one of them. This is interesting because he’s also generally considered the greatest Renaissance composer, and this graffito is the only surviving thing written in his own hand.

The great artists of the Renaissance were most often Italian — Michelangelo, da Vinci, Caravaggio, Raphael, Donatello. But as often as not, the best composers of the Renaissance were Franco-Flemish, meaning they were from northern Europe and had trouble clearing their throats.

Like most northern composers of the period, Josquin — usually referred to by the one name, like Plato or Beyoncé, and pronounced zhoss-KAN — spent most of his career in Italy, where wealthy families were engaged in the most artistically productive pissing contest of all time, to which Josquin contributed many powerful and elegant streams.

He was acknowledged as the greatest composer of his generation within his own lifetime, which is rare but nice. Like Bach two centuries later, Josquin wrote both sacred and secular works and excelled at both. The sacred music is really stunning:

1:12

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3qx_JjPrh5M” parameters=”end=72″ /]

But he could also let his hair down with secular songs. Here’s a frottola (the precursor to madrigal) about a cricket — short, funny, and kind of amazing:

El grillo, El grillo è buon cantore | The cricket is a good singer

che tiene longo verso | and he sings for a long time

Dalle beve grillo canta. | Give him a drink so he can go on singing

Ma non fa come gli altri uccelli | But he doesn’t do what the other birds do

come li han cantato un poco | Who after singing a little

van’ de fatto in altro loco | Just go elsewhere

sempre el grillo sta pur saldo | The cricket is always steadfast

Quando la maggior è [l’] caldo | When it is hottest

alhor canta sol per amore. | then he sings just for love

1:30

15. JOSQUIN frottola “El Grillo” (The Cricket) (1:30)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OI-bQ0RkArA” /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | 13 Mozart | 14 Reich | 15 Josquin | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale on Facebook:

Podcast Ep. 2: The Strange DNA of a Surf Song

Wisrgallery CC BY-SA 4.0

Episode 2 of HOW MUSIC DOES THAT – The Podcast looks at the unexpected history behind the edgy guitar tune that opens Pulp Fiction.

Listen to “Ep 2: The Strange DNA of a Surf Song” on Spreaker.

Age Stories: How My Kids Met Me One Year at a Time

“Twenty-eight!”

“Hmm, okay, 28. Ooh, that’s a good one.”

Despite living with him for 13 years, I knew very little about my dad. He worked three jobs and traveled a lot. When he was in town, he came home exhausted from a hundred-mile round-trip commute. I didn’t even know he was a nonbeliever until long after his death at 45.

My mom spoke very little of him, consumed as she was with the lonely and impossible task of working full-time while raising three kids by herself two time zones away from any other family.

I’ve wondered how much my kids would remember of me if I died today. The situation is different — I’m more involved in their lives than my dad was able to be in mine, for several reasons — but I wanted a way of sharing my life with my kids that was natural and unforced.

At some point, without even meaning to, I found a way, starting a tradition in our family called “age stories.” Simple premise: At bedtime, in addition to books or songs, the kids could pick an age (“Twenty-eight!”) and I would tell them about something that happened to me at that age. For a long time it was one of their favorite bedtime options.

Through age stories, they now know about my life at age 4 (broken arm from walking on a row of metal trash cans), age 9 (stole a pack of Rollos from Target and felt so bad I fed them to my dog, nearly killing her), age 21 (broke up with my first girlfriend and got dumped by the second one), 23 (my crushing uncertainty on graduating college), 25 (the strange and cool job in LA that allowed me to meet Nixon, Reagan, Bush Sr., Jimmy Stewart, Elton John, and a hundred other celebs), 26 (when I pursued and stole their mother’s affections from the Air Force pilot she was allllmost engaged to), what happened on the days they were born, and everything — eventually just about everything — in-between.

They know how I tricked a friend into quitting pot (for a night anyway, at 15), the surreal week that followed my dad’s death (13), how I nearly cut off two fingers by reaching under a running lawnmower (17, shut up), my battles with the administration of the Catholic college where I taught (40), the time I was nearly hit by a train in Germany (38) and nearly blown off a cliff in a windstorm in Scotland (42).

Age stories can also open up important issues in an unforced way. Delaney happened to ask for 11 — my age when my parents moved us from St. Louis to LA — right before we moved her from Minneapolis to Atlanta. It was a very difficult time for her. I described my own tears and rage at 11, and the fact that I held on to my bedpost the day of the move — and how well it turned out in the end. I wasn’t surprised when she said “11” again and again during that hard transition in her own life.

We’ve talked about love, lust, death, fear, joy, lying, courage, cowardice, mistakes, triumphs, uncertainty, embarrassment, and the personal search for meaning in ways that no lecture could ever manage. They’ve come to know their dad not just as the aging monkey he is now, but as a little boy, a teenager, a twenty-something, stumbling up the very path they’re on now.

And they keep coming back for more.

Give it a try. Make it dramatic. Include lots of details and dialogue. Have fun. Then come back here and tell us how it went.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tR-qQcNT_fY” /]