Look, It’s Just Cool (Reich Sextet)

- June 10, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

5 min

(#6 in the Laney’s List series — a music prof chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

Five composers especially haunt Laney’s List, coming back 3-4 times each. Four I could have predicted — Chopin, Bach, Mozart, Ravel. But until I started whittling, I didn’t know I’d give minimalist Steve Reich a trifecta as well.

Minimalism is the pendulum swing that followed the mid-20th century throwing-a-chair-while-barking school of it-is-totally-music-yuh-huh-is-so composition. It is mostly triads and conventional harmony, mostly simple patterns slowly changing over time, and represented a major palate cleanser after the avant garde of Varèse et al.

Terry Riley and Philip Glass are the emblematic pioneers of minimalism. But just as it’s Chopin representing the nocturne in this list, not Irish composer and nocturne inventor John “Who?” Field, so Reich is my go-to for minimalism. And in this list, like a good minimalist, he repeats.

Minimalism is not for everyone, so I’m starting in the relative shallows — a short interior movement of Reich’s Sextet for four percussionists and two pianos (1985). No major analysis required — it’s just cool. Things I love:

- The great contrast between those dense, massive hits of mixed dry and wet sound and that telegraphic vibraphone.

- The surprisingly chill melodic figure in the vibes at 0:26, like a ring tone interrupting General Patton’s speech.

- The way those two characters interact for the rest of the short movement.

I think nearly everything Reich does is interesting and cool, but I know it’s not for everyone. That’s why I’ve included three pieces of his in the list, increasing in conceptual difficulty. As Germany can tell you, sometimes it takes three Reichs to know they just aren’t your thing.

REICH, “Slow” from Sextet

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbTZdEnu2yo” /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Chopin Had Just One Request (Impromptu No. 4)

- June 07, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

6 min

(#5 in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

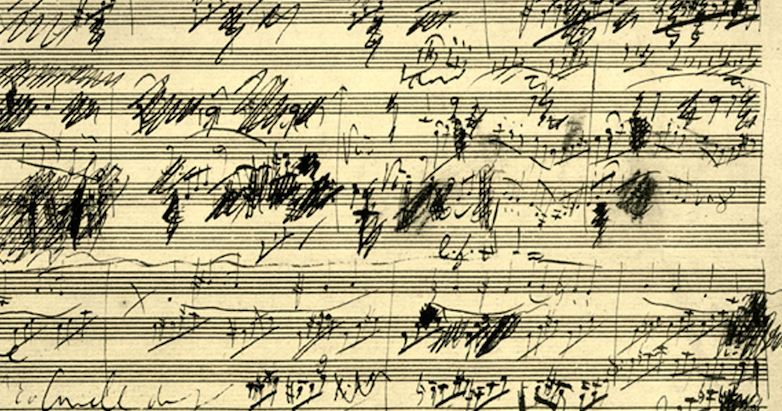

If Chopin had his way, you wouldn’t know his Impromptu No. 4. Written in 1834 when he was 24 years old, it was not published until he was 45, by which time he had stopped writing new works entirely, having been dead for six years.

He had asked nicely that his unpublished works (including this one) remain unpublished after his death, which seems reasonable. But Posterity invoked the legal principle quid facietis in hac — roughly, What are you going to do about it? — and published anyway. It is now among his most performed pieces.

It starts with the fantastic agitated energy of his etudes, then goes into a tranquil melody that he clearly borrowed from the Judy Garland song “I’m Always Chasing Rainbows.”

Enjoy.

CHOPIN, Impromptu No. 4 (4:50)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UplCACM5MC0″ /]

See also: 1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow me on Facebook:

The Most Elegant Two Measures in the History of Oh My Gawd (Bach ‘Air’)

- June 06, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

8 min

(#4 in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

If you gave me ten seconds to name the most gorgeously crafted, unsurpassably elegant masterpiece of musical art ever created in Western music, I would say, “Air from Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite in D, also known as ‘Air on the G String'” and ask what you’d like me to do with the other six seconds.

The list of reasons is long and wonky, but I’ll stop at two.

1. The Bass Line

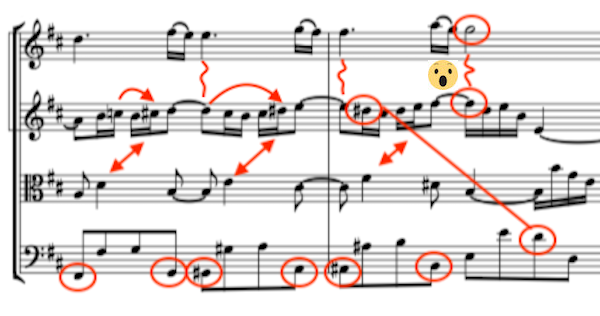

A bass line descending by step was common in the Baroque — part of something called the “doctrine of affections,” a way of signaling a particular emotion. Bach could have done something like this

or maybe an octave higher

Instead, he weaves elegantly between the octaves: down / up up / down down…

It’s such a graceful variation on a common idea. Follow the purple squares on the visualization for a few bars to see how it unfolds (15 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2j-frfK-yg” parameters=”start=16 end=32″ /]

2. The Most Elegant Two Measures in the History of Oh My Gawd

About halfway through is a two-bar passage that manages to somehow surpass everything that came before. The progression is not just chords but a smooth series of mini key changes — G major, A major, B minor, E minor. See all those sharps sprinkled in there as it rolls by? That’s Bach altering chords along the way to point to new keys, all hung on a bass line of rising half steps. The result is this rich tapestry of sound that builds tension with a dissonance on each downbeat, ending on that brief, searing G against F# in the violins. It’s an eight-beat master class in voice leading and harmony from the Lord High Commander of both.

Listen to those two measures (14 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2j-frfK-yg” parameters=”start=156 end=170″ /]

Now forget all that and enjoy the piece my wife and I chose as her wedding processional 27 years ago.

BACH, ‘Air’ from Third Orchestral Suite in D (5:00)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2j-frfK-yg” parameters=”start=15″ /]

Hildegard’s Spooky, Dangerous Little Note

- June 05, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

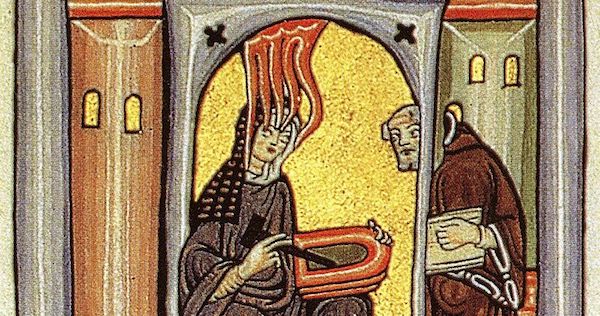

Usually these portraits of a composer passing on divinely-inspired music to a scribe featured Pope Gregory the Great (after whom Gregorian chant is misnamed). Having a woman in that chair shows the extraordinary place Hildegard occupied during her lifetime. From the Scivias manuscript (1151).

(#3 in the Laney’s List series — a music prof chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

Think of a revolutionary moment in music history. Beethoven’s 9th? The Rite of Spring? Schoenberg’s tone row? Piffle. The real revolution was the first time one pitch was sung at the same time as another — the first harmony.

There’s no way to know when that first happened, but we do know that early Jewish and Christian music was monophonic (one note at a time). The purity of a single tone was thought to be most appropriate for worship. Harmony introduces ratios of vibration, which introduces the dissonance spectrum, and Beelzebob’s your uncle.

Composers started easing into harmony in the 10th and 11th centuries, first putting simple drones under chant melodies, then doubling the chant melody at the fourth or fifth, then stretching the chant into long notes with florid melody above. Certain intervals were banned by the church, but by the 13th century all hell breaks loose, and the full chordal harmony of the Renaissance isn’t far behind.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was an abbess musician living and working in the middle of that revolution. Her music is often described as “otherworldly” or “mystical,” especially when she uses a drone and the Phrygian mode, which she does quite a bit. Phrygian is the same as a minor scale with one exception — the second note is only a half step above the tonic, so you get a lovely clash between them. Play a white-key scale on the piano starting on E and you’ll get a Phrygian scale. (Not if you’re pregnant, though: Pregnant women as far back as Golden Age Greece were not allowed to hear the Phrygian mode because the dissonant relationships between the pitches could summon demons.)

The drone in “O virtus” below is on the tonic and dominant (E and B), and the E Phrygian melody includes an F, which clashes yummily with that E drone as it passes by. You can hear that at 0:14, 0:36, and 0:52, etc. That delicious, spooky little Phrygian cloud passing over the harmony is Hildegard’s special sauce, the dangerous note that makes it otherworldly.

HILDEGARD, O virtus sapientiae (2:12)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-TsaHn2kcGc” /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | Full list | YouTube playlist

Follow me on Facebook:

And You Thought You Knew Scarlatti

- June 03, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

(#2 in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music. Back to #1)

If you made it to the second year of piano lessons, you probably know Domenico Scarlatti. After months of patiently listening to you lightly rowing and informing relatives about the demise of waterfowl, Mrs. Mawdsley told you in hushed tones that your hard work had paid off. You were ready at last for real music. You were ready for Scarlatti.

He wrote 555 keyboard sonatas, and some of them were simple and sedate enough for small, sticky fingers:

(16 sec)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L7-DUGSjTdY” parameters=”start=6 end=22″ /]

But about 499 of his sonatas are entirely else.

Scarlatti spent most of his career writing brilliant, inventive, dynamic bursts of keyboard fireworks for the Spanish and Portuguese courts, and these Scarlatti sonatas probably never made it to your music stand. But after she bye-byed you out the door, poured herself a Bloody Mary and let down her messy piano teacher bun, it was this Scarlatti that Mrs. Mawdsley invited into her living room. This Scarlatti will blow your hair back. This Scarlatti is so much fun it hurts.

Watch the amazing Martha Argerich shred this one.

SCARLATTI Sonata in D Minor K 141

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjghYFgt8Zk” parameters=”start=3″ /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Chopin and the Chopinuplets (Nocturne in B-Flat Minor)

- June 02, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In The List

0

0

(First in the Laney’s List series — a music professor chooses 36 pieces to introduce his 16-year-old daughter to classical music.)

The soundtrack of my childhood came through my brother’s piano in three threads: West Side Story, Scott Joplin, and Chopin. He played other things, but those are the ones I can still hear — and it’s Chopin that makes me feel five years old again. I would sometimes lie beneath the keyboard by the pedals with my back against the piano as he played nocturnes, picturing that tortured, tubercular Delacroix painting ^ on the cover of Ron’s music. Chopin is warm and dark and safe and sad to me, but it’s also the physical vibrations of that piano against my back.

All that to say: I don’t approach Chopin objectively.

The nocturne is meant to evoke the calm of night, and Chopin’s Nocturne in B-Flat Minor is no exception. But there are exceptions. When my son was four, he listened to a CD of Chopin nocturnes to go to sleep. That was fine until we left it running longer than usual and learned what Nocturne No. 13 does in the middle. Heh.

There’s a lot to talk about in the B-Flat Minor nocturne — including theorythings like the lowered sixth in major (0:29) and the spooky Neapolitan harmonies (1:11) that give Chopin his Chopiness — but I want to keep it short on these posts.

The thing I love most about this one is his liberation of the melody from the beat.

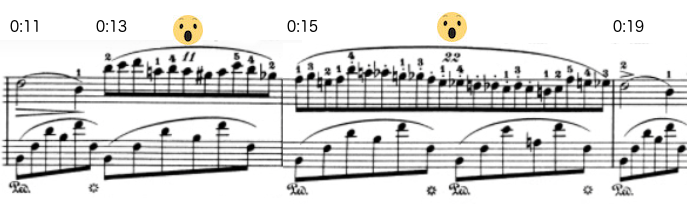

In the first bar, the right hand establishes that flow of eighth notes, six notes every half bar. The left hand dutifully takes over the flow, 1-2-3-4-5-6/1-2-3-4-5-6. Then at 0:13, as the left continues to churn out those sixes, the right hand suddenly gets naked and dances on the table:

Instead of six notes per half bar, the melody bursts into this effusive chromatic flow of 33 notes where 18 “should” be. Those Chopinuplets are saying screw your strict divisions, my soul is singing. A great interpreter (like Rubinstein below) frees that spirit even further by stretching the beats, allowing all those notes room to breathe. That’s Romanticism, and it happens again and again in the 20 nocturnes.

Now forget all that and enjoy.

CHOPIN, Nocturne in B-Flat Minor, op. 9 No. 1

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZtIW2r1EalM” /]

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

In Which a Dad Foists Ancient Music on a Defenseless Child

- June 02, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In Listen

0

0

The title is a lie. There was no foisting, the music isn’t ancient, and she is defenseful.

Lemme start over.

My daughter Delaney (16) has a huge music listening range, and lately she’s been adding classical to that. When I offered to make a summer listening list, she was all in.

It wasn’t a list of the “greatest” music she needed — just a sampler, enough to maybe pique her interest in going further. I set a hard limit of five listening hours and started choosing my team. Picture Bach and Copland in gym shorts shuffling their feet, Ravel confidently looking at his impeccable nails, and Salieri thinking, “Not last, please just not last.”

Some fish leapt right into the boat. No list of mine is going to leave out Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta — even a top five, maybe even three. Same with the Stravinsky Octet. And I knew there’d be a feckton of Chopin, though I wasn’t sure yet which.

Some old flames didn’t get an invite to the wedding. Bach’s Goldberg Variations is a planetary treasure, but a big part of that is how it develops over the course of an hour. “Nobody gets a damn hour” seemed like a reasonable ground rule, so Goldberg was out. I surprised myself by including zero symphonies but three piano concertos, what? And I made an executive decision not to include film music, the modern descendant of the classical tradition. I’ll do a separate list of film scores someday.

With the help of friends, the list grew to 52, then I whittled, ending up with 36 pieces by 24 composers spanning 900 years and 4.75 listening hours. Happy to hear how your own list would differ, but thanks in advance for refraining from “WUT?! None of the mid-period ocarina sonatas of Mamflamheim?!?” as well as any use of the word “unconscionable.” kthxbi

Here’s the list, and here are recordings on a single page. The order is intentionally odd. I’ll blog through the list over the course of the summer, and I’d love to have you join me for that.

LANEY’S LIST

1. CHOPIN Nocturne in B-flat Minor, op. 9 no. 1

2. SCARLATTI Sonata in D Minor K141

3. HILDEGARD O virtus sapientiae

4. BACH “Air” from Third Orchestral Suite in D

5. CHOPIN Impromptu No 4 in C-sharp Minor

6. REICH “Slow” from Sextet

7. DELIBES “Flower Duet” from Lakmé

8. RAVEL “Prelude” from Le Tombeau de Couperin (piano)

9. RAVEL “Alborada del Gracioso” from Miroirs (orchestra)

10. BOULANGER Vieille Priére Bouddhique

11. DEBUSSY Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

12. GINASTERA “Dance of the Arrogant Cowboy” from Danzas Argentinas

13. MOZART “Lachrimosa” from Requiem Mass

14. REICH Electric Counterpoint

15. JOSQUIN madrigal “El Grillo” (The Cricket)

16. COPLAND Appalachian Spring Suite

17. CHOPIN Nocturne in D-flat Major, op 27 no. 2

18. PUCCINI “Nessum Dorma” from Turandot

19. WHITACRE Lux Aurumque

20. HOLST from The Planets suite: Mars, Jupiter, Uranus, Neptune

21. MOZART “Adagio” from Serenade No 10

22. STRAVINSKY Octet for Wind Instruments, three mvts

23. PART Fratres for strings and percussion

24. COPLAND Fanfare for the Common Man

25. TOWER Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman

26. CHOPIN “Minute” Waltz in D-flat major op. 64 no. 1

27. MOZART Piano Concerto No 21, mvt. 2

28. RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Major, three mvts

29. BACH Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, mvt. 1

30. JOSQUIN De profundis clamavi

31. BARBER Adagio for Strings

31. STAVELEY-TAYLOR “Take Me Home”

32. BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp Minor “Moonlight”, mvt 1

33. REICH Piano Phase

34. BACH “Prelude” from Cello Suite No 1 in G

35. BARTOK Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, mvts 1 and 2

36. RACHMANINOFF Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor, mvt 1

The recordings on one page…and as a YouTube playlist. (Thanks to Marcus Monkeyman!)

The Most Hopeful Music in the World

- May 11, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In Mind Blown

0

0

It’s hard to know when to broach the subject of mid-20th century radical modernist composers with your kids. My daughter was sitting quietly at age six when I decided it was time.

“You’re performing a piece of music, you know.”

She looked up at me with the tired patience of a child of mine. I said a man named John Cage wrote a piece of music that was nothing but four minutes and 33 seconds of silence. She was playing it perfectly.

She thought for a second, then nodded. Then I told her about another piece by Cage — and this one so captured her imagination that she still mentions it ten years later.

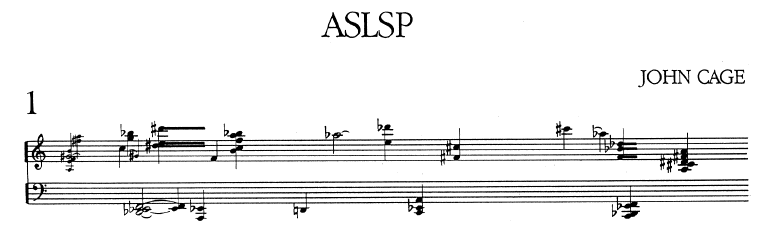

As Slow as Possible is a piece for organ. It usually runs 20-70 minutes, depending on how seriously you take the title. But if you take it literally, it raises a real question: how slow IS as slow as possible?

A group of musicians and philosophers discussed that at a conference after his death, deciding in the end that the determining factor would be how long it would take before the instrument it was played on fell apart. The oldest installed pipe organ in Europe at the time was 639 years old and about to give up the ghost.

“So they decided to play it really slow — so slow that it would last for 639 years,” I said. “They found an empty church in Germany and built a little organ. It started playing on September 5th, 2001. But the music starts with a rest – a silence – so the first thing they heard was nothing. For seventeen months!”

“Haha!” she said. “That’s weird.”

“And right in the middle of that silence—you were born.”

She thought about it, then whispered: “Awesome.”

“Then one day, when you were one year old, the first note started to play. Hundreds of people came to the church to hear it. Most of the time it’s playing with no one there. Little weights hold down the keys. Then every couple of years, it’s time for the note to change, and people come from around the world to hear that.”

“And it’s playing now?”

“Yeah, it’s playing right now. And here’s the thing: It’ll be playing on the moment you graduate from high school. It’ll be playing when you get your first job, when you get married, and when your kids are born. The music that started the year you were born will still be playing at the end of your life. It will be playing when your grandchildren are born and when they die, and their grandchildren, and on and on for 639 years.”

This project will strike some people as silly. There was a time it would have hit me that way. But the more I think about the longest piece of music, the more it moves me.

The organ in Halberstadt currently playing ASLSP by John Cage.

Suppose someone had started playing a piece of music in Halberstadt 639 years ago, in 1379. Only a generation had passed since the Black Death slew a third of Europe. The music would have ushered in the Renaissance, the voyages of the New World explorers, and the Scientific Revolution.

The religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries would have raged around it. It would have been playing as Halberstadt changed hands from Prussia to Napoleon’s Westphalia and back to Prussia before becoming part of Saxony, then Germany, playing as Allied bombs fell in 1945, as the town was closed into communist East Germany and as it was returned to the heart of a reunified Germany.

Would that piece have reached the last note?

Starting a piece of music implies an intention to finish it, so starting a 639-year long piece is an extraordinary act of optimism. It implies that we might still be here in 639 years, and that the intervening generations, with all of their own concerns and values and ordeals, will pick up the baton and run with the project we had begun, marking their calendars to visit the church and shift the weights when the time arrives.

I don’t care what the music sounds like, by the way. It’s the idea that moves me, makes me think. To hear the notes currently being played is to connect yourself to the recent past and the distant future.

So long as we can keep from killing each other, cooking the planet, or blowing up Halberstadt with technologies still undreamt, then maybe our optimism will have been justified. The hopeful music will finish.

Meanwhile, every few years for the rest of my life, she and I will both think about this little organ playing in a church in Germany.

The current chord:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SVPHOD3hN84″ parameters=”start=8″ /]

The Cage interview

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pcHnL7aS64Y” parameters=”end=59″/]

Follow Dale on Facebook:

The Fifth Beatle Was a Robot

One of the most amazing things about (Western tonal) music is how much variety has tumbled out of a few basic materials. Twelve pitches in four triads in two main modes, maybe ten basic rhythms and a half dozen common meters and 20 instruments — shake well, and out pours Danny Boy and Mozart’s Lacrimosa and So What and Uptown Funk and the Nokia Tune and Sacred Harp 457 and madrigals and national anthems and this and this and god help us Happy Birthday. Millions and millions and millions of unique pieces created by repeatedly dipping a pan into the same stream, then picking through the nuggets.

What distinguishes one genre from another, or one composer or band from another, is the choices made among those nuggets. Handle harmony and rhythm and timbre in one way and you’re Bach, another and you’re Brahms, another and you’re nobody. Same with pop music. The reason you can tell the Stones from Coldplay is largely about the different approaches they take to the elements of music.

Scientists at SONY CSL Research Lab fed huge amounts of data from Beatles songs — choices made in harmony, melody, instrumentation, etc — into an algorithm that then composed a “typical” Beatles song. Uh…enjoy?

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSHZ_b05W7o” title=”Daddy’s Car: A Song Composed by AI” /]

It’s a little uncanny in that slightly queasy way, but I’ve got to admit — the essence is absolutely there.

So what is it that’s so bang-on Beatles-y?

There’s that rhythmic flow that starts at 0:05 (quarters in the drums, dotted quarter/eighth in the bass, eighth note strum in the rhythm guitar), the falsetto background vocals, the George Martin tubular bells, trippy background voices, all Beatles favorites. All good stuff. But it’s the harmony that our robot overlord has gotten (if I may say so, Your Excellency) exactly right.

[Be advised that the following includes theoryspeak. If that isn’t your thing, just listen at the times provided. You’ll get the idea.]

The drifty ahhhhh at the very beginning makes a slippery diminished triad. Which way is up, where is home? It doesn’t much help when the full harmony comes in (0:05): First there’s a triad that isn’t a triad (B C# F#), then an F# major triad, then A minor. It’s still hard to know where home is because no key contains both F# major and A minor chords. Then suddenly, boom, we’re in the key of B minor at 0:12, though the progression that follows is not at all typical.

We modulate to A minor (0:39), then to G major (0:47). A and G are close to B and to each other on the keyboard, but they are on different planets harmonically. So we have not only crossed into three different keys in under a minute, but three wildly unrelated keys, and gracefully at that.

Starting at 0:47 we get a progression that is all Beatle: G-A7-C-G, or I – V7/V – IV – I. Just listen to 0:47-1:07 and try to think of any other band. Then keep going a few seconds for the very cool jump back to B minor at 1:09.

“Down ON THE ground” (0:39- ) might be the most Beatlish spot in the whole thing. “ON” is a non-chord tone called an appoggiatura — a leap to a note that’s not in the chord, then a step in the opposite direction to resolve, something in a lot of Beatles songs — and it’s over a descending chromatic scale in wavery guitar, another fingerprint of theirs.

So if you wonder what made The Beatles The Beatles and everyone else everyone else — it’s mostly about the harmony. Sure, they wrote some four-chord pop songs. But the songs that really left a mark include harmonic adventures that no one else even approached. And even if you don’t know a thing about theory, you can hear it and feel it.

If you are fuming about the idea of a computer performing a credible facsimile of the human creative process, take heart. It’s easier to imitate than to create an original piece of genius. No robot has written the equivalent of “Eleanor Rigby” or “Because.”

Yet.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

The Real Inspiration for The Simpsons Theme – And No, It’s Not ‘Maria’

5 min

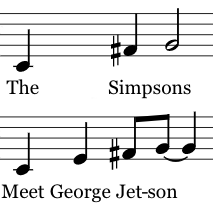

When in the last post I suggested that a trumpet lick in The Simpsons was an homage to “Something’s Coming” from West Side Story, I didn’t mention an even more obvious parallel — that the first three notes of Simpsons exactly equal the first three notes of the main melody of “Maria”:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpdB6CN7jww” parameters=”start=39 end=42″ /]

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1r2EbNSymjE” parameters=”start=2 end=5″ /]

Here’s why I left it out: Unlike the trumpet lick, the opening of the Simpsons theme was definitely not inspired by “Maria.” Elfman was paying tribute to something, but it wasn’t West Side Story. It was The Jetsons.

Back in the 1990s, if a producer really really liked a composer, he would give him a mix tape. As The Simpsons was in development, Matt Groening gave Danny Elfman a tape with all of his favorite cartoon music. He loved the music for Warner Bros. cartoons and Tom & Jerry, but he didn’t want to use that technique known as “mickeymousing” in which the music closely parrots the action on screen. That left Hanna Barbera, including Groening’s favorite cartoon theme of all: “I loved The Jetsons theme the best,” he said.

In no time, Elfman cranked out an iconic theme with a headmotive that bears a striking resemblance to his boss’s favorite:

Also not a coincidence: both are in that unusual Lydian dominant mode I banged on about last time — 4 up and 7 down.

Oh but that’s not all. The whole Simpsons opening sequence is an inside-out parody of The Jetsons opening sequence. In The Jetsons, you start with blue sky and Dad driving away from home. Two kids go to school, then Mom goes shopping, then Dad arrives at work. In The Simpsons, you start with blue sky and Dad driving FROM work, Mom leaves the store, the kids leave school, and they all converge at home.

Both openings are below. For maximum fun, play them at the same time. For more convincing, listen to the short Groening interview below.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1r2EbNSymjE” /]

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eSptqzfTSSE” parameters=”start=8 ” /]

Here’s the smoking gun:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UthzUr0rFQ” /]

Feature image Ludie Cochrane CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr