Could it Be? Yes It Could! Simpsons Coming, Simpsons Good

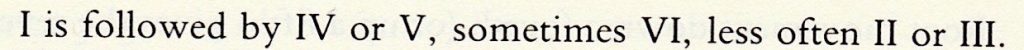

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

It jumped out at me the first time I saw the show, probably 1990, and I was immediately convinced that composer Danny Elfman meant to do it. This morning I decided to find his email address to ask him.

In the process of looking for his email, I learned that Elfman’s violin concerto Eleven Eleven just premiered at Stanford’s Bing Hall, and realized that asking him about the goddamn Simpsons theme is like saying “Hello? Is it me you’re looking for?” into Lionel Ritchie’s answering machine, and I recognized that The Simpsons is the equivalent of a catchphrase for Elfman, a good thing that you spawned long ago that continues to nip at your heels for the rest of your life, and that asking about The Simpsons instead of Eleven Eleven in 2018 is like walking up to De Niro on the street and saying, “You talkin’ to me?” and thinking one’s self very clever, so I stopped looking for his email address.

But still, there’s this Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

First you need to know that The Simpsons theme is not in major or minor. It’s in a mode called Lydian dominant. Start with a major scale, then raise the fourth step and lower the seventh, like so:

You’ve heard music in some form of Lydian mode a million times, mostly in movies and musicals. It tends to convey goofiness when fast, childlike wonder when slow. The Simpsons is an example of the fast and goofy; here are two from the childlike wonder department:

(8 sec)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZTbn97-Wws” parameters=”end=08″ /]

(16 sec, and you’ll wish for more)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_t98LWNwUhI” parameters=”start=96 end=113″ /]

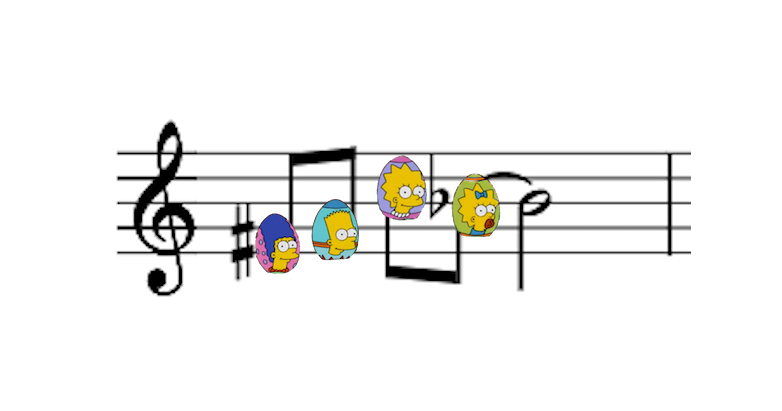

Now to the Easter egg. It’s the trumpet lick at 51 seconds:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xqog63KOANc” parameters=”start=51 end=53″ /]

A very distinctive little motive, innit, including both of those unusual Lydian dominant pitches. In fact, I’m pretty sure I’ve only heard that exact thing in one other place. Listen to Tony from West Side Story when he sings the words “maybe tonight” twice at 2:43:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xu7sRdRrm_w” parameters=”start=162 end=169″ /]

Those exact pitches in that exact shape and rhythm, appearing by chance in The Simpsons? Naw. It’s homage, I tells ya, homage. But only Danny Elfman knows for sure, and I’m not asking.

On Solving the Musical Mystery of My Life

- March 14, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In Emotion

0

0

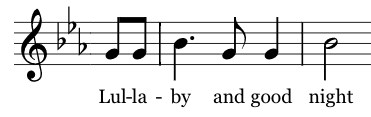

Ever since I was a wee babe, one song made me spontaneously burst into tears — Brahms’ Lullaby (“Lullaby, and good night,” etc.). My parents first discovered this because the mobile above the crib played it, and every time they wound the infernal thing up, I’d shriek until it stopped.

For at least the first 20 years of my life, just a few notes of Brahms’ Lullaby would draw a convulsive wet snurk from my face. My brothers loved this and would miss no opportunity, ever. In the middle of a long, quiet car trip, Older Brother would quietly hum the first few notes so only I could hear, and I would thump him, and I’d get in trouble, which was So Unfair. Even worse were the times Younger Brother made me cry, which disrupted the whole Order of Things.

Worst of all was the fact that I didn’t know why it did that to me. It was bizarre.

Barber’s Adagio for Strings (as I may have mentioned) also makes me cry, but that one slays me gradually for reasons I can explain. The Brahms was always immediate and impossible to account for. My family advanced various theories, my favorite of which was that I was the reincarnation of Brahms’ wife and I missed him. But if that were the case, I figure the Academic Festival Overture would also choke me up.

I’m over it now, mostly, but I never stopped wondering what that was all about. I even tore apart the theory of it, which in this case was like tearing into tissue paper: it’s all I and V and IV with nothing more adventurous than a couple of passing tones in the melody. Shocking modulations and searing appoggiaturas are pretty thin on the ground in lullabies.

My older brother suggested it might be the recurring minor third motive:

the shape of which does rather imitate the Universal Taunting Melody (“Nanny Nanny Boo Boo,” BWV 386b):

I like that idea, but I suspect being bothered by the UTM requires a level of emotional registration that was still in my future at that point. And though I’d have put my figured bass harmonizations up against any other toddler in South St. Louis in 1965, my motivic analysis was still sub par.

And then, a few days ago, more than 50 years after first blood, I suddenly solved the musical mystery of my life. The answer was so obvious that I’m a little embarrassed, especially since you figured it out in the first paragraph, didn’t you.

My parents would wind up the mobile, start the tune, and then leave.

That has to be it. Brahms’ Lullaby was my soundtrack of abandonment. As I cried, that melody tinkled above me. Later, I’d hear the tinkle and the tears would flow.

This would have been solved 30 years ago if I’d stuck with the psych major, but I went into music theory. So like the guy who looks for his wallet under the streetlight instead of back in the alley where he dropped it because the light is better, I spent all those years hammering a nail with a screwdriver because…uh, the light was better.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=46eJ6OoATRg” /]

Follow on Facebook:

Why Does Surf Rock Sound Vaguely…Middle Eastern?

12 min

Most musicians have a mild hatred of scales because we were all forced to practice and memorize them without anyone ever telling us what the hell they are.

I mentioned before that a scale is the palette of pitches with which a specific piece of music is painted. If you’re a composer in the West, you generally go into a paint store of 12 available pitches (the chromatic scale) and choose a subset of pitches for the emotional quality you want, essentially a palette of colors for the piece. Most of the time we choose one of two palettes: major or minor. It’s amazing how much great music has come out of those two palettes.

Once in a while we alter a single pitch to make something like the Dorian mode (Michael Jackson’s favorite, which takes a minor scale and bumps the sixth pitch up a click). If you change more than that, the scale begins to sound exotic, and that’s especially true if you create a step that’s not present in major or minor. The second step of the scale, for example, is a whole step above the tonic pitch in both major and minor, like the do-re in do-re-mi. So if your tonic is C and instead of going to D, you go to D-flat…well, even if you know nothing about music theory, your ear is instantly intweeged. If you want to paint Spanish Flamenco Dancer or Indian Snake-Charmer, or Some Kind of Vague Middle-Easternness, flat the 6 as well and you get this:

It’s called a Byzantine scale, one of several that appears in folk music throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Saint-Saëns sets up the climactic Bacchanale from Samson and Delilah by putting the Byzantine scale in a sinewy oboe. That scale is all you need to say “ooh, kinda biblical”:

0:24

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/TEhor3HeulE” parameters=”start=9 end=33″ /]

The Byzantine scale also appears in a place that is crazily incongruous and somehow brilliant — Dick Dale’s surf rock anthem “Misirlou.” The rapid-fire guitar, backbeat drums, and exotic scale made it the perfect heart-racing opening for Pulp Fiction. I’ve included the terribly upsetting profanity that precedes it because — well Tarantino, first of all, but also it’s part of the emotional crescendo that makes the song selection so spot-on:

1:40

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/oOoBomvuYnw” parameters=”start=20 end=56″ /]

God I love the cool, sinister energy of that song. (Dick Dale’s complete “Misirlou” is at the end of the post.)

As it turns out, Dick Dale wasn’t just borrowing the scale for his surf anthem. “Misirlou” is a remake of a vaguely Middle-Eastern traditional song, possible Egyptian or Turkish, first recorded in Greece in 1927. The whole melody finds its way into the Dick Dale version:

1:17

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/LW6qGy3RtwY” parameters=”start=19 end=86″ /]

As it further turns out, Dick Dale’s connection to the scale isn’t crazily random. Dale was of Lebanese descent on his father’s side and grew up playing the tarabaki drum and hearing music based on these scales, which he then incorporated into his surf music.

Here’s the tarabaki (aka doumbek) in the hands of a master:

0:29

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/FYlWrI9C-pI” parameters=”start=12 end=72″ /]

Grow up in Southern California with Byzantine scales in your ears and a tarabaki rhythm under your hands and you’ll create something like this:

2:15

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/-y3h9p_c5-M” /]

Dick Dale photo by Paul Townsend CC BY-SA 2.0

Follow Dale on Facebook:

3 Ways the ‘Office’ Theme IS Michael Scott

Michael Scott, the hapless regional manager in The Office, is one of the great characters in television. That mix of blustering confidence in his mouth and self-doubt in his eyes is a picture of striving lameness — a mediocrity who has somehow convinced circus management he’s a high-wire walker, then suddenly finds himself 50 feet above a pit of flaming tigers, naked, deciding whether to spend the surplus on a new copier or chairs.

Steve Carell captures this perfectly in the character of Michael Scott. The show’s theme manages to do the same in music, three ways in 30 seconds.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/uyIVAm9PVrI” /]

1. Dat accordion

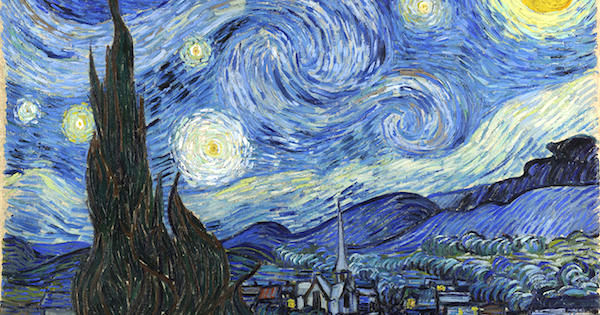

First there’s the choice of instrument for the melody. When an accordion is going full tilt boogie, chords and all, it can be incredible. But a single, reedy, wheezy little solo accordion line is the essence of striving lameness, reaching for Van Gogh’s Starry Night and managing only a velvet Elvis. It is Michael Scott.

2. Dat clash

The second is less obvious but even more important. Here’s where the accordion enters in measure 5. Top line is the accordion; middle line is piano; bottom line is bass:

The chord progression is simple: G-Bm-Em-C, almost but not quite the four chords every pop song is made of. Here it is simplified to block chords:

Something weird happens in the second bar. See how the wheezy accordion in the top line hangs on a G from the previous bar? Now look at the harmony in the second bar — specifically the lowest note in the middle staff. It moves from G in the first measure to F# in the second, even as the accordion hangs on G up above. The harmony is right — it’s a B minor triad. But Accordion Michael Scott is oblivious to the fact that the harmony changed beneath him. Because of course he is.

If they had both hung on and changed at the same time, it might have been a pretty thing called a 6-5 suspension. Instead, for two full beats we get G and F# mashing against each other like Steve and Melissa at the 25th reunion.

I’ll isolate those two lines and draw them out with a good trumpet patch in the audio:

Audio:

Hear that clash in the second bar? It’s intentionally wrong. It’s hamfisted and lame. It’s Michael Scott. And it happens twice in eight bars.

3. Rock on

So what do you do if you’re Michael Scott and you’ve just done something hamfisted and lame, twice? You double down, cue the drummer, and rock on:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/uyIVAm9PVrI” parameters=”start=15″ /]

THAT is the most Michael thing of all.

Follow on Facebook:

Porn for Music Theoryheads

(18 min and worth it)

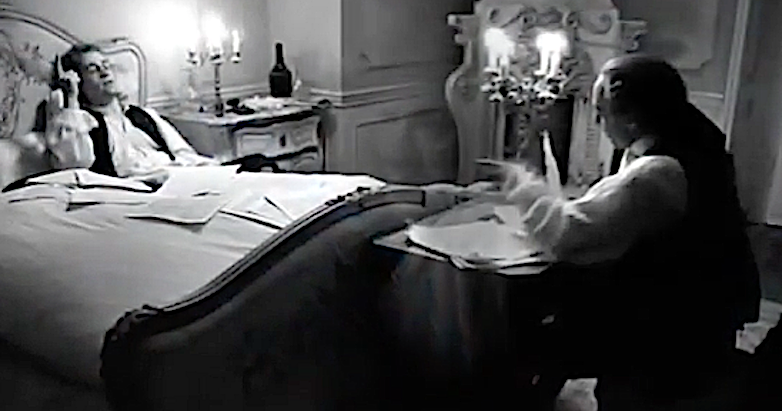

To a certain kind of musician, the deathbed dictation scene from Amadeus was everything:

It was a courageous scene to even try. “Second measure, fourth beat on D. All right? Fourth measure, second beat – F!” is not generally Academy-bait banter, as Tom Hulce notes in this great behind-the-scenes clip:

And now, after thinking that scene couldn’t get any better, I stumble on this brilliant gem. For an even smaller subset of musicians — the kind that likes to peel back the skin and see the gleaming bones — this is just porn:

(Extra Credit: Find the theory error in the dialogue and put it in the comments.)

The Most Essential Element of Music

Music is a hard thing to study or talk about for one big reason: it can’t stop moving. Aside from film, visual art tends to stand still, allowing the viewer some control over the experience. But music moves forward, relentlessly, thwarting our attempts to get a firm grip.

Suppose you tell a friend that you went to the Van Gogh exhibit at MOMA yesterday, and she asks, “How long was the exhibit?” The question doesn’t really make sense. At best, you’ll take it to mean, “How long does it take to go through?” That depends. Your answer could be six minutes, an hour, or all day. There isn’t a set duration for visual art.

But if you say, “I went to hear a Brahms concert yesterday,” and she asks how long the concert was, it’s a sensible question. Two hours and five minutes.

The difference is a critical one. At the Van Gogh exhibit, you could look at each painting for three minutes or skip entire rooms. Stand and gawk at “The Starry Night” for hours. Get in close for a look at one brushstroke. Step back, cross your arms pretentiously, and you can see the whole thing at once. You can compare one part to another, move your eye left and right and left again, top to bottom, leave the room for a potty break and come right back to looking at the waves crashing on the shore.

Stare at those waves for 20 minutes if you want. Realize they’re not waves. Compare background to foreground. Time is not a constraint.

Now on to the concert. The first piece begins. At any given moment you are experiencing only a fraction of the entire piece, one moment in time, and as soon as it happens it is gone, replaced by another and another in a sequence you cannot change. You can’t move your ears from left to right and back again at will, and you certainly can’t step back and look at the whole piece at once.

You also can’t stand up and yell, “Stop! Hold it right there so I can really listen to that moment!” Even if concert security doesn’t drag you out, holding one moment of the music destroys it. All you would hear is the chord at that moment, no rhythm, no meter, no tempo. All the elements of time, so crucial to making music what it is, are fatally suspended. You might as well try to understand the processes of the human body by saying, “Hold that heartbeat and breathing still for a few minutes.”

“If you take a cat apart to see how it works,” said Douglas Adams, “the first thing you have on your hands is a non-working cat.”

Visual art transmits meaning with shape and color distributed through space. Music transmits meaning with pitch and (tone) color distributed through time. This is the heart of the difference between music and visual art, and the heart of the difference in what each can and cannot do. The thing that makes music hard to study also gives it an advantage in capturing lived emotional experience. Like life, music flows.

Life unfolds, one moment after another. Plans are made, expectations built up, then they are fulfilled, or delayed, or dashed on the rocks, over time. The fact that music shares that critical element with life itself—that it unfolds gradually—is key to understanding its power to move us.

Click Like below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

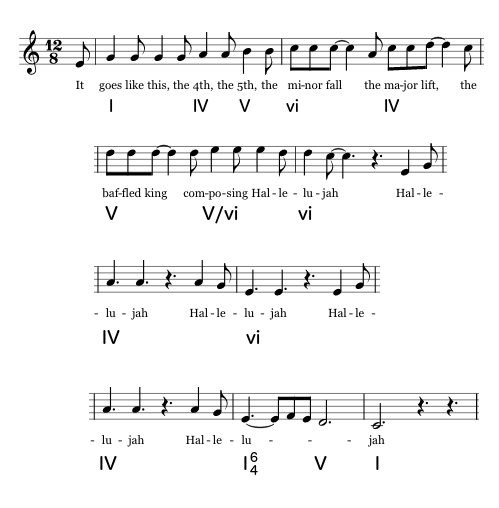

Yabbut…Why THOSE Four Chords?

A few years ago, the comedy-rock band Axis of Awesome pointed out a great truth — that every pop song ever written uses the same four chords in the same order.

The fact that it’s not really true makes it no less impressive. I mean, every single song!

Enjoy a couple minutes of this, then we’ll talk.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/5pidokakU4I” parameters=”end=139″ /]

So maybe it’s not every song, but it is a helluva lot of songs using the exact same progression somewhere in it. The video puts them all in E major, which makes the progression

E – B – c# – A

Putting all of the songs in the same key is not cheating — it’s still the same progression, just like “Happy Birthday” is the same festering turd of a tune no matter how much helium you inhale. Likewise, this is the same chord progression no matter what chord you start on. If you’re in C, it’s C-G-a-F. If you’re in A, it’s A-E-f#-D. But it all boils down to this:

I – V – vi – IV

So why are songwriters addicted to I-V-vi-IV? Because for a basic progression, it’s actually pretty effective. Not a thing of genius, just a really solid workhorse. It’s been robbed of its sparkle by overuse, but it’s worth taking apart to see why it has become such a go-to.

I

It starts with I, the tonic, because most of the music you’ve heard, like most of the stories you’ve heard, starts at home. The question is where we go next. That’s easy:

V

As I said in The Hidden Grammar of Music, the most common place for any chord to go is up or down a fifth, and the tonic chord is no exception. In this progression, the I chord goes to the chord it is most closely related to, the dominant, the neon arrow: V.

Now the obvious thing for V to do is spring right back to I. Happens all the time:

The aforementioned “Happy Birthday” does exactly that. But a good chord progression (like a good sentence, story, meal, relationship) should include a little of the unexpected. Since we just did an obvious thing (I-V), we should do something less obvious next. So instead of going back to I, we go to

vi

Remember the deceptive cadence I introduced in the post about Cohen’s Hallelujah? That’s the idea. Instead of going home to I as it was born to do, V can go to vi, the relative minor. It’s interesting — a wee bit of shadow falls across the progression. And as the Hidden Grammar post pointed out,

Only one chord to go. But which one? We could repeat I, V, or vi, but that’d be boring. We want something new to round out the phrase. There are four other chords in the key. Which would be the most satisfying?

Here’s a thought: Each of the chords we’ve heard so far is made up of three pitches from the seven-note scale. When you rack up the pitches in those chords, we’ve heard six of the seven pitches:

You don’t know it, but your ear is thirsty for that missing fourth note. In the key of E, that’s an A. The chord built on that pitch is A major, or (ta-da!)…

IV

All together, then:

As a bonus, when you repeat the progression, IV goes back home to I in a very satisfying and common progression called the plagal or “Amen” cadence.

None of this makes the I-V-vi-IV progression inevitable, but it does make it sensible as a recurring thing, like subject-verb-adjective-object in written language.

Nutshell: If you start in the most common starting place, make the most common harmonic move, follow it with something just a little different, then fill in the one remaining gap in the scale, you get the most common pop progression on Earth.

Friends Don’t Let Friends Clap on 1 and 3

In a post called The (Actual) Evolution of Cool, I described the difference between cool and non-cool music using Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition” and a Sousa march. TL;DR: Putting the emphasis in unexpected places tickles the cerebellum’s timekeeper, which simulates danger, which feels cool.

One way to inject the unexpected into music is by emphasizing the offbeats. If a song has four beats per measure, as most do, beats 1 and 3 are strong beats, the obvious places to put your emphasis. Polka bands, marches, and hymns all emphasize 1 and 3.

But if you want to be even cooler than a hymn, throw the emphasis to the offbeats — one-TWO-three-FOUR.

Harry Connick Jr. is a cool guy, but his audience is mostly white suburban moms, sorry, which means the clapping is gonna be on 1 and 3, which kills the feels. And the particular kind of New Orleans jazz he plays can teeter between cool and square, so a little push from the wrong side of the beat is death.

The concert clip below starts with 40 seconds of painful 1-3 clapping, and sure enough, Connick’s piano sounds rinky dink. But right at 0:40 Connick adds a beat, turning one of the four-beat measures into a five-beat measure. The audience just keeps clapping on every other beat, but now they’re on 2 and 4, and everybody wins. You can see the drummer exulting in the background when he realizes that Connick saved the swing:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UinRq_29jPk” /]

Genius move.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

h/t Rob Tarr | Top image by Stephanie Schoyer Creative Commons 2.0

Title inspiration via Drummer’s Resource

The Long Exile in Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah

When Leonard Cohen died at 82, he left us more than 100 songs, most of which I don’t know. But there’s one that’s almost universally known and adored: “Hallelujah.” One reason for that success is an effective use of the tools of harmony.

Start by listening to the first verse and chorus (58 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/Qt2FWAbXinY” parameters=”end=58″ /]

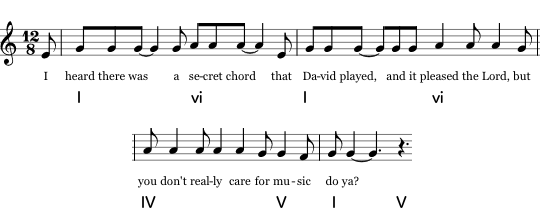

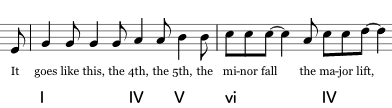

Let’s take it apart a bit. We’re in C major, so the tonic chord, the emotional home, is a C triad (I). Here’s the first phrase with Romans:

That’s a comfortable, homey phrase of music. The melody winds around G, the reassuringly stable dominant pitch. The harmony is also fully domesticated, touching home (I) three times and the dominant (V) twice. We’re 15 seconds in, and all is well.

The chords at the end of a phrase make up a kind of emotional punctuation called the cadence. This phrase ended on V, which is common. It’s called a half cadence, the musical equivalent of a comma. There’s an unresolved, up-in-the-air feeling because you’re pointing home without actually going home (7 sec):

Feel the dangle? That’s a half cadence.

Now before we get to the magic, let’s geek out on some music theory Easter eggs Cohen has hidden in the next phrase:

“The 4th” is over a IV chord; “the 5th” is over a V; “minor fall” is a minor triad and “major lift” is a major triad. That’s adorable.

For the real magic, we need to zoom out and look at eight measures:

The melody forms a beautiful, yearning arc, starting from middle E (“it goes”), reaching up to high E (“composing”), then falling through more than an octave to middle C on the last Hallelujah. Here it is simplified:

Gorgeous. But as usual, it’s the harmony that conveys the main emotional story.

(Stick with me now. This is cool and comprehensible, and a good window into how music works.)

Remember how the first 4-bar phrase kept coming home to the tonic? I -vi-I -vi-IV-V-I? That made it homey and comfortable. Now look at the chords for these next two phrases — 8 long, slow bars:

I IV V vi IV V V/vi vi | IV vi IV I6/4 V I

We leave home (I) on “It goes like this,” then wander in exile for what is (musically speaking) a very long time. Along the way, we keep encountering LIES. The third chord is a V (on “the 5th”), which promises home…but instead of I , we get pulled sideways to vi, the minor. That’s disconcerting, but okay.

Two chords later there’s another V, another promise of home. But the chord after it — the one that looks like a fraction — isn’t even in the key! A minor chord in our home key has been changed into a major chord, becoming a dominant arrow for another key entirely. It’s called a secondary dominant. In this case it’s the dominant of A minor (vi), which leads strongly to vi. Going from V to vi is called a deceptive cadence , for good reason: it’s a damn lie.

The first vi was disconcerting. The second, stronger one is more so. Twice we were promised our C major home, and twice we ended up on A minor instead. The second one was even tonicized, which is what you call it when a dominant of its very own was created to emphasize it.

As we head into the chorus (“Hallelujah…”), we get a IV. Ooh, I know this one! It could be the first part of a plagal cadence (IV-I), also known as the “amen” because it closes every church hymn. That’ll take us home through another door, like so — and I’ll make it nice and churchy (11 sec):

Amen, see? That would have grounded the phrase and ended our exile. But…it doesn’t do that. We don’t go home. Instead, the IV goes unexpectedly to vi, and we’re pulled sideways to the A minor dark side for a THIRD time (11 sec):

The first one takes us home and tucks us into our bed; the second pivots to our dark minor lake cabin in winter, and the firewood is wet, and the horn just blew three times.

At this point it’s been a full 30 seconds since we’ve been home, an eternity on this scale. Worse still, we’ve been teased with home three times. Cohen has us feeling subconsciously homesick. Then finally, finally, we get a V that isn’t a lie. It promises home and delivers, moving to a I on the last syllable of the last Hallelujah. It’s an authentic cadence, V-I, the musical equivalent of a period, full stop.

Here’s my favorite cover of the song. Feel the security of that first phrase, then leave home, wander in the desert as home is thrice denied, then feel the return on the last Hallelujah of the chorus. Beautiful.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y8AWFf7EAc4″ parameters=”start=69″ /]

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Top image by Bill Strain | CC 2.0

Lou Rawls and the Christmas Clams

I hate to do this.

Lou Rawls is one of my favorite R&B singers. “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” is one of the most harmonically delicious Christmas songs. So you’d think the Lou Rawls cover of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” would make me happy. But it doesn’t — all because of one phrase.

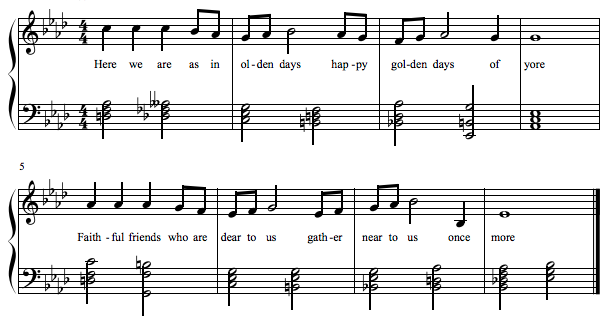

I know this is a little stupid. Most of the cover is perfection. The band is tight, and Lou is on his game. I’m having myself a merry, as requested. But just over a minute in, on “faithful friends who are dear to us,” Lou lays down a series of clams so painful that I want to gently place my fingertips on the crowning head of baby Jesus and stuff him back in.

Let’s listen from the beginning, up to the spot that pees on my Yule log (75 sec):

The harmony in this song is rich and gorgeous, especially in the bridge:

It’s taking all of my restraint to not run naked and giggling through the Romans on this one. Those of you who would understand it can do the analysis your own fine selves. For the rest, here’s a slow jam on the harmony (32s):

It’s taking all of my restraint to not run naked and giggling through the Romans on this one. Those of you who would understand it can do the analysis your own fine selves. For the rest, here’s a slow jam on the harmony (32s):

A lot of the wonder in this passage is in the relationship of the melody to the harmony. There’s a chain of dissonances that still play by the rules of harmony. The bass note and melody note form one dissonant interval after another — sevenths and ninths and tritones. But in the context of the full harmony, every note of that tune is either part of the chord or what’s called a non-harmonic tone — a note that’s not in the chord of the moment, but follows one of a dozen established patterns that your ear can make sense of. This passage was not written overnight. Picture one of those guys who paints landscapes on the head of a pin.

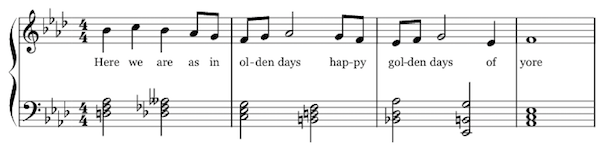

If you’re a jazz singer, futzing around with the melody is part of the job description. But when the harmony is as complex as this, it’s a lot harder to thread that needle. Rawls starts the bridge like so:

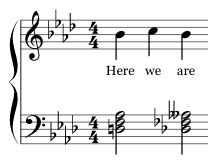

I’ve straightened out the rhythm for comparison to the original, but notice the pitches. Instead of singing three Cs for “Here we are,” he sing Bb-C-Bb. Nice touch. He’s now off by one step for the rest of the phrase…

…and it works anyway! Jazz harmony is greatly expanded compared to classical harmony. Instead of three-note triads, you have 7th chords (with 4 notes), 9th chords (with 5 notes), and so on. More pitches are eligible to sound at any given moment. You can go off script and still win, and that’s what he did here. Every melody note nestles into its chord as either a chord tone or a legal non-harmonic. To translate that to jazz, Lou laid no clams in those four bars, only pearls.

Oh, but the next two bars.

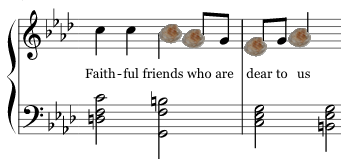

Flush with that victory, Lou decides to sing the same basic phrase again. But the harmony under it has changed, a lot. The result is a clambake:

You don’t need to be a music theorist to hear it. Here they are together: listen to how the first phrase works, and the second phrase (“Faithful friends”) doesn’t (15 sec):

<silent scream>

I know what you’re thinking. I’m a petty little man, and he’s Lou Rawls. But imagine that for years you’ve adored the genius that went into one tiny corner of a beautiful painting, a detail that no one else seems to notice or comment on. Then one day you see someone walk by and squirt their clam sandwich onto that exact spot. I don’t care if it was Michelangelo himself who bit the sandwich, you’re still gonna be pissed.

I love you Mr. Rawls, but dude, napkin.