The Pitch Ceiling: You Make It to Break It

- June 09, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

Remember 12-year-old Grace VanderWaal on America’s Got Talent? Sure you do.

4:03

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNxO9MpQ2vA” parameters=”end=243″ /]

Give me a minute. I’m a sucker for that kind of thing.

Okay.

I’m not the only one. A friend of mine said she cries at 2:03, every time, and she wanted to know why. First the obvious: Adorable munchkin who has apparently seen Juno 20 times sings about not knowing who she is, then suddenly belts out, “I now know my name!” Dead. I’m dead.

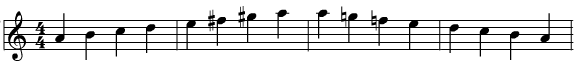

But as usual, it’s not just the words. In the hands of a good songwriter, the music intensifies the meaning of the words. Yeah, the tempo picks up and she sings louder at that spot, but there’s something else there. Over the course of the short song, she creates a kind of pitch “ceiling” — then breaks through it at the perfect time.

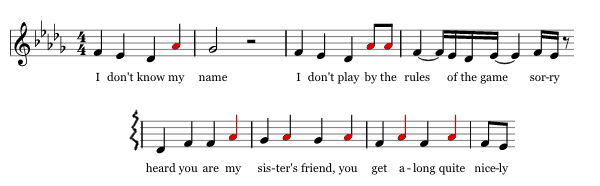

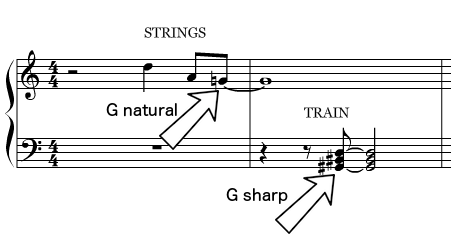

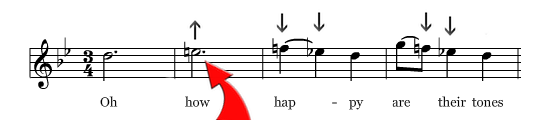

Listen to the A-flats (in red below). She keeps hitting that note over and over and doesn’t go above it for most of the song:

The repetition creates a really tangible boundary. Listen:

16 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNxO9MpQ2vA” parameters=”start=76 end=93″ /]

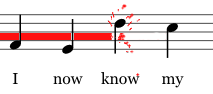

…then her breakthrough in the lyrics is mirrored with a breakthrough in the music, and the crowd responds instantly:

5 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNxO9MpQ2vA” parameters=”start=122 end=127″ /]

That moment was the difference between polite applause and the audience leaping to its feet.

Simon Cowell’s “you’re the next Taylor Swift” comment was a bit much. But if Grace does happen to make it big, she’ll be able to trace her success back to a single well-placed D-flat.

Follow me on Facebook:

Harmony is What Happens to the Hero

As a kid, I knew chords were a lot of notes played at once. And I thought I knew why we had them: Melodies sound too plain by themselves, so we add chords to kind of fill it in, like the background of a painting.

I got better. The relationship between melody and chords (harmony) is much more interesting. We follow the melody like a hero. Behind and around the hero, the harmony provides an unfolding emotional story. It can be a simple home/away/home again story, or more of a leave home, get hit by bus, go to hospital, fall through trapdoor into your own bedroom and discover it was a dream kind of story.

The harmony is not just scenery — it’s what is happening to the hero. To understand how that works, we’ve got to get into the weeds a bit. Bear with me — cool toys are coming, and you’ll need these tools to play with them.

Each basic chord (or triad) consists of three pitches, like words consist of letters. Chords in combination communicate emotion, just as words in combination communicate meaning.

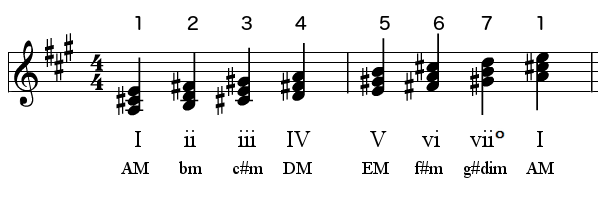

Keys don’t consist of seven notes so much as seven chords (triads). To build those triads, start with the seven notes of the C major scale (plus C again on top):

Now stack pitches on top of them in thirds.

Reminder: From one pitch to the next in the scale is a second, so C to E is a third, as is D to F, E to G, F# to Ab, etc. Doesn’t matter if sharps or flats are involved — it might be a different kind of third (major, minor, augmented, diminished), but it’s still a third:

Start with a note, add a third above it, then add another third above that one. You end up with stacks of three notes on the lines, or three notes in the spaces, like so:

These are the building blocks of musical meaning. Now let me add some information:

If it feels like the first time you looked at a periodic table, steady on — this is easier than it looks. Like the periodic table, it packs in a huge amount of powerful information once you know how to look at it.

The three lines of symbols contain different information about the triads. The digits on top are the simple degrees of the scale itself — the bottom note of each triad, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7, which in C major is C-D-E-F-G-A-B.

The bottom line is what you see on guitar music. These show the pitch on which each triad is based (also called the root of the triad) and the form the triad takes. Uppercase is major, lowercase is minor, and “dim” is diminished (more on that eventually).

The line of Roman numerals is just a way of combining the other two. The Arabic digit (like 5) becomes a Roman numeral (V), and the case of the Roman indicates major or minor. (The little degree circle means diminished.)

We can do the same thing with any starting pitch, any scale. The A major scale has C, F, and G sharped (raised by a half step) to fit the whole-step/half-step pattern of the major scale:

…and so on for any pitch, any scale. The chord symbols on the bottom change, but the Romans stay the same because the chords are fulfilling the same function in each key — the same “words” with a different home (I). I’ll be using the Romans a lot from now on to talk about what’s going on in the harmony of a piece. If I say the chords are I vi IV, it means you hear a major triad built on the first note of the scale, then a minor triad on the sixth note, then a major triad on the fourth note. But instead of 27 words, I use three symbols: I vi IV.

These three-note triads, much more so than the notes of the scale, are the emotional words of music, the bricks out of which everything is built.

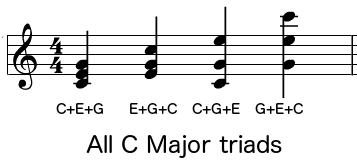

One important point: In the actual music, the notes don’t have to be in that order. They can be exploded out in any order top to bottom. This just reduces it to what’s called simple position, with the notes in the closest possible intervals to figure out what chords they are. Kind of like putting all the letters of a word in alphabetical order, except in music the meaning doesn’t change.

These are all C major triads, for example:

The composer might spread them out like that for different textures and effects. But if I want to figure out what’s going on in the harmony, I can put the last three in simple position with C on the bottom, and their harmonic identity becomes clear.

Okay, back to the triads of C major:

I remember being surprised to learn that a major key consists mostly of non-major chords. But it’s a good thing it does — that variety makes it work, giving you a road map so you know where you are relative to home. And your ear knows how to follow that map. Of course it does — you’ve passed this way ten thousands times before.

As the music moves along through time, left to right, it passes through different chords, and the sequence of chords makes us feel a certain emotional narrative. Same as language: These phrases start with the same three words, but the last three lead to very different places:

- For sale: baby turtles, too cute!

- For sale: baby shoes, never worn.

It works the same in music. Suppose you hear a major chord alone — let’s say it’s an F major triad:

Is that the tonic home? Dunno. It is if we’re in F major. But an F major chord could also be IV in the key of C. Can I get an amen, people:

Or V, the neon arrow, pointing to a Bb home:

In each case, before we could know what the F triad means, we needed another reference point. Once you have two chords, your ear starts to triangulate on home. Let’s say we hear two major triads next to each other, ascending — F major and G major:

When you look at the map for a major key, there’s only one place with two adjacent major chords, one place it fits in the aural landscape — IV to V.

And here’s the crazy great thing. You don’t need to see the map or know the Romans. When your ear hears an F major triad, then a G major triad, your ear instantly knows where home is. Sing it! You know where it’s going! Sing where it’s going, dammit!

C major is home.

So that’s a simple example of starting somewhere harmonically (F) and ending up at different homes (F, Bb, and C). That’s the tip of the tip of the iceberg. Composers use these ambiguities to mess with you, moment to moment, leading you to expect one direction and giving you another. It’s like those “garden path” sentences:

- The old man the boat; the young watch from shore.

- The man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

- The cotton clothing is made of grows in Mississippi.

- Mary gave the child the dog bit a Band-Aid.

Back to music for a while, including some unweaving that goes further into the harmony/hero relationship.

If you’re new here, or you want to review, you can start at the first post, or work your way through Just Enough Theory in the right sidebar. Quick and fun.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

House of Cards: Screw Your Happy Ending

- May 05, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

A good opening title sequence moves you to a different emotional place — Walter White’s desert meth lab or a purgatorial island or Don Draper’s 1960s Manhattan — usually in 10-60 seconds.

The House of Cards theme is longer: apparently it takes a full 96 seconds to piss on the last sputtering embers of your faith in democracy. Pission accomplished:

Within 4 seconds, something’s wrong. The key (or tonic, or home) is vague because we aren’t hearing full three-note chords, just two notes at a time in rising thirds. It’s like playing Wheel of Fortune — we only have some of the letters in each word, and we’re trying to figure out the meaning of the phrase.

Your brain draws on a lifetime of listening, ten thousand songs that followed the same basic rules, then uses that experience to piece together clues about where home is this time. It does this by filling in the seven slots of the scale. So far we have E, F, G, A, Bb, and C — six out of seven! — so your brain is pretty sure that F is home. That would sound like this (8 sec):

That’s where we were headed — F Major! If we got there, the show would have been Mr. Rogers instead of Mr. Underwood. Instead, right after hitting that Bb, he drops us to the ‘wrong’ key — A minor (8 sec):

The result is that Underwood feeling (8 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9w-O60x1bYk” parameters=”end=08″ /]

The same progression signals each entrance to the Pit of Despair in The Princess Bride. Different key, same queasy effect (8 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BbgyppGqBgg” parameters=”end=08″ /]

Back in DC, the clouds roll in, and the encroaching shadow takes the city from bright busy daylight down through dirty underpasses and into the pulsing heart of darkness. The heartbeat bass recasts the high-speed traffic as arterial blood. The heroic statues drown in darkness, in sync with the distant drums and trumpets — a bitter parody of patriotism.

By the time that heartbeat bass fades out at the end, the milk of human kindness sits curdled in the cat’s dish, the cat is dead, and Frank Underwood is talking about two kinds of pain.

And I’m ready.

That bass line stays the same from start to finish. It’s a technique called ground bass or basso ostinato — literally “stubborn bass” — a simple pattern in the bass that repeats over and over, creating a unified emotion, even as the rest of the music varies above it.

In the early 17th century, different ostinati were used to signal different specific emotions. The descending minor four-note bass figure in Monteverdi’s gorgeous Lamento della ninfa signaled sadness (36 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3ZX5hFN-is” parameters=”start=96 end=138″ /]

Pachelbel’s Canon in D uses the same device, this time with an eight-note ostinato. You know the tune:

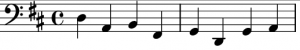

The bass in the House of Cards theme is also telegraphing an emotion — and it’s pretty much Frank Underwood’s initials, if ya feel me. The key of A minor is drilled home in the most elemental way it can, 1 to 3, A-C-A-C. Composer Jeff Beal referred to that bass as “the stubbornness of Frank,” underpinning everything and refusing to change course. The rest of the harmony is also in A minor at first. It breaks into a barely perceptible A major at 0:48, then back to minor at 0:58 before ending in that kind of heroic, operatic A major starting at 1:18.

Switching to major at the end of a minor piece is called a Picardy third — you bump the third note of the scale up a half step to major, and the sun breaks through the clouds. Here’s Bach at the end of a minor piece giving one of his clients a happy ending (26 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E4Y29VsSvuQ#” parameters=”start=404″ /]

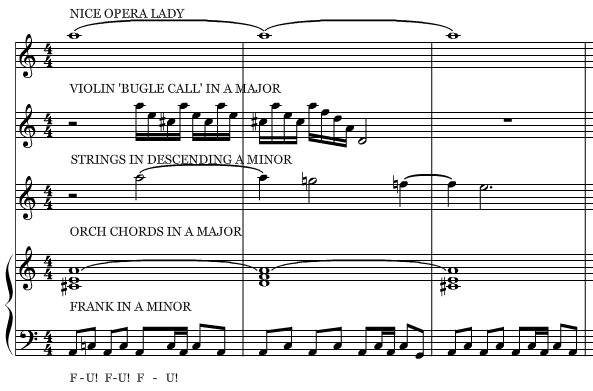

But the “heroic, operatic A major” in House of Cards has a wee bit of poo stuck to it. Just as the Valkyrie comes in on that high A, and the strings are cranking away on the fast A major bugle call, that high violin falls through a descending melodic minor. And the wicked C in the bass is rubbing up against the happy C# in the strings. Bad touch, stranger danger!

As the major key tapers out, we’re left with Frank crapping on your happy ending (20 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/9w-O60x1bYk#” parameters=”start=76″ /]

Then There’s the Mickeymousing

When I studied film scoring at UCLA, a few things were verboten. “Wallpapering” was one — that’s when the music never, ever shuts up. The composer feels the need to prime every emotional shift and even physical gestures. Very big in the 1930s-50s, not so much now.

Another no-no was “mickeymousing,” the word for music that closely mimics visual details in the scene. Steamboat Willie (1928) was the first to do it — hence the name — and Looney Tunes amped it up to 11 — think of the xylophone mimicking the Coyote tiptoeing away from the pile of Acme dynamite.

The House of Cards opening theme includes mickeymousing that actually works. It’s crisp and subtle, for one thing. Watch how the visuals are synched to the slightly jarring drum hits — sunlight flashes on the houses on the first drum stroke (at 0:11), cars halt on the second stroke (at 0:13):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/9w-O60x1bYk#” parameters=”start=08 end=15″ /]

But my favorite mickeymouse moment is also the best spot in the whole theme, establishing a harmony that haunts the whole series. As the train flashes by, a chord sounds, mimicking a train’s horn, synched to the visual right at 1:09:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/9w-O60x1bYk#” parameters=”start=58 end=72″ /]

Here’s that great chord:

That chord is why I took a detour to melodic minor in the last post. Remember the melodic minor scale, with the 6th and 7th raised going up and lowered again going down:

So G# and G-natural are both legal in A minor — the key of House of Cards. In this case, it uses those two clashing notes at the same time, producing a very cool dissonance that composer Jeff Beal inserts frequently in tense scenes throughout the series. Each time it’s an echo of that train, hurtling through the darkness.

More on that chord and other brilliant cues from House of Cards in a later post.

A Minor Detour, To Jethro Tull and Bach

I want to write about the House of Cards theme, but first I have to talk about my obsession in middle school band. No, not the Hannah twins. I’m talking about a musical question that haunted me: Why is the melodic minor scale different going up and going down?

I know: If I had the head space to be haunted by the melodic minor, I clearly hadn’t read enough Camus. But I eventually figured it out, so I could turn at last to the fundamental absurdity of human existence.

Here’s the A melodic minor scale:

Hear it? The 6th and 7th notes (or degrees) in the scale are raised on the way up (F# and G#) and lowered again on the way down (F and G).

To understand why that is, notice that melodic minor has melodic right in the name. It’s the scale that dictates the form pitches take in a minor key when they are in sequence, one after the other, like a melody.

The message of the melodic minor scale is this: if your melody is going upward, raise the 6th and 7th notes. If not, don’t.

That still doesn’t explain why. For that, you need to know one thing: notes are lazy.

Suppose a note is not in the chord of the moment — this is called a nonharmonic tone, more on that later — and it’s between two pitches that are in the chord. Moving either way would resolve the tension of being nonharmonic. But if one of those pitches is a whole step away, and the other a half step, the note in the middle will tend to move to the closer pitch, like an electron jumping to the nearest valence.

Remember Dorothy last time, hanging on that leading tone, windmilling her arms before reaching toward the tonic home a half step away?

That’s the power of the leading tone, just a tantalizing half step away from the tonic. Minor keys want a piece of that magnetic action too. But the 7th note of a minor scale is a big boring whole step from the tonic.

Nothing compelling there, no irresistible attraction to the tonic, no windmilling arms. To add to its humiliation, when the 7th pitch is a whole step below the tonic, it isn’t even called a leading tone — it’s the “subtonic.” Sick burn. It’s bumping elbows with the tonic, but not leading toward it in any particular way.

So instead, when a melody in minor is going from the 7th pitch to the tonic, it borrows the leading tone from major, raising 7 a half step, making it a true leading tone to the tonic:

Instant attraction!

Okay, but why is the 6th note raised? Because when you bump the 7th note up, the distance from 6 to 7 becomes a step and a half, a.k.a. an augmented 2nd, which stands out against the half and whole steps, sounding like Aladdin just magic-carpeted into the room:

Can’t have that. A lot of Western tonal theory is about creating a unified musical texture so you can respond to the emotional language of the whole without individual elements suddenly drawing your attention like passing squirrels. The absence of bagpipes in the orchestra, the rule against parallel fifths, and avoiding augmented 2nds are just a few of the ways traditional Western theory keeps your attention on the big picture.

So to avoid the augmented second from that raised leading tone, let’s raise the 6th note. This also keeps it from wanting to fall back to the 5th note, the powerful dominant, when you’re ascending. If you keep it lowered, it’s only a half step away from that delicious dominant, and that’s allllll it wants (10 sec, turn it up a bit):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRZAk2rfESU” parameters=”end=10″ /]

You feel that?? We’re in B minor here, so the top note G is the 6th, unraised. And each time you hear that unraised G, you can feel the magnetic pull down to F#, the dominant (5), just a half step below.

That’s great if that’s where your melody is headed, like it is in the Batman theme. But to break the pull and go up, you raise the 6th and 7th. Imagine after a couple of times through that motif above, Elfman wanted a triumphant ending. It might have sounded like this:

That time I raised the 6th to G#, which continued up to A#, then home to B. The line was going up, so 6 and 7 are raised.

These adjustments also just make minor melodies flow better as the 6th and 7th lean in the direction they are headed. Carol of the Bells is a great example:

9 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_LiccvcXdeI” parameters=”start=21 end=30″ /]

One note in Carol of the Bells gives me chills every time — a raised 6 as the tenors sing, “Oh how happy are their tones.” The word HOW is raised, then “happy are their tones” turns around and cascades over it:

5 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_LiccvcXdeI” parameters=”start=17 end=22″ /]

That spot, that one note, is thrilling, unexpected. Now you know why — it’s the sudden brightness of the raised 6th degree.

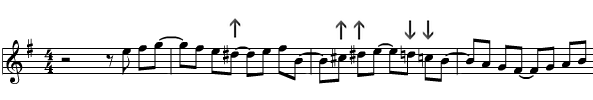

I’ll finish with the best example of the melodic minor in its natural habitat, one that takes me back to middle school again — Jethro Tull’s Bourrée:

15 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N2RNe2jwHE0″ parameters=”start=5 end=21″ /]

(I hear Bach did a remake of this, but I’m too much a fan of the original.)

Okay — now we can talk about House of Cards.

Home and the Neon Arrow

10 min

Just about every piece of music you’ve heard starts with a question: Where is home? A lot of the emotional power of the music, moment to moment and beginning to end, has to do with leaving home and finding our way back.

We’ve told this story for as long as we’ve told stories. It’s Gilgamesh, the Odyssey, and the Garden of Eden, the Hindu Muchukunda and the Welsh Gwion Bach. It’s Gone with the Wind, The Martian, Exodus, Battlestar Galactica, Gilligan’s Island, Gravity, Lost, Cast Away, all three Toy Stories (especially 2), Back to the Future, Planet of the Apes…and the films that elevated home-lust to a fine art: The Wizard of Oz and E.T.

In The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell suggested that every myth and legend we’ve ever told is a variation on a basic story he calls the monomyth. The hero leaves home, crosses into the unknown (usually by besting a guardian), meets a mentor, faces challenges and temptations, is transformed, and returns home, usually bearing a gift, totem, or special knowledge. Shake well and you get Prometheus, Star Wars, the New Testament, Lord of the Rings, and a million more.

I don’t know about “every myth,” but I get it. This narrative is huge.

Music works the same way. Composers establish home in a few ways, including the key, then they take you away. Sometimes it’s just a few seconds at a time — pop in on the neighbors, then home again, then out to the folks on the other side, then home again, all in a single verse. Or the music might take you for a long drive, then come back to the neighborhood, only to pull into the wrong driveway. It can also take you away from home and never bring you back. You start the day in F major, get stranded in D, and by the end of the piece, you’re stuck in the suburbs of B minor, working for an insurance company and living for the weekend.

I hinted at this in the scales post:

This pattern [of pitches in the scale] creates a kind of aural map. The sequence of half and whole steps sticks a pin in one of the notes, calling it home, then creates a series of landmarks to tell you where you are relative to that home at all times. By listening to music all your life, your ear has learned how to follow that map — to go away from home, have adventures, and return (or not). The next three JET posts will get into that.

And here we are, getting into it.

Part of the complex texture of musical communication is that all of this home-and-away drama happens not just on the scale of the whole piece, but measure by measure, phrase by phrase. There’s even the ability to encode different home-and-away messages in melody and harmony at the same time–I’ll show you how that works in a bit. As usual, you don’t have to know how it’s done, or even that it’s happening at all, for it to work.

But knowing is nice, so let’s do that.

First, a little proof of concept:

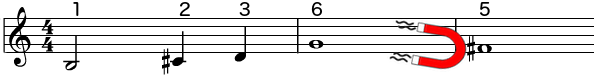

If you sang the last note like a little cheater, consider yourself Mozart. When he was 4, Mozart’s father is said to have rousted Wolfgang out of bed each day by playing the first 7 notes of the scale on the harpsichord, do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti… The slappable little prodigy would leap out of bed, unable to bear the musical unresolvedness of it all, run into the parlor, and play the last note: do!

Whatever.

True or not, the story rests on a true thing: the 7th note of the scale is fabulously unstable, known perfectly as the leading tone. It’s the last thing before you get back to the key note, which is “home” in music. You can feel home right next door. Not only that, it’s just a half step away from the tonic home. So the leading tone feels like it’s standing with its toes over the edge of a cliff, windmilling its arms, trying to keep from toppling forward onto the tonic. And not trying all that hard.

Dorothy’s final “can’t” (Why oh why caaaaaaan’t…) is on a leading tone.

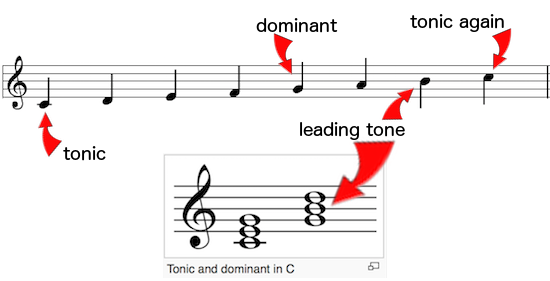

But for all its cliff-edge windmilling, the leading tone isn’t where the real home-pointing power is. There’s another relationship that’s more important for deep emotional direction. It’s the tonic’s relationship to the 5th note of the scale, known as the dominant. The chord built on that pitch is a big neon arrow pointing home. If you’re in C, then C is the tonic and G is the dominant:

Listen to those last three notes, 1-5-1. The first note is home. The second note moves away. The third feels like a return home, back to the center of the tonal universe.

But single pitches are just a shadow of the real juice–the harmony. Build triads on those pitches and you can really feel it. Triads are designated with Roman numerals, so the chords built on the pitches 1-5-1 are called I-V-I. Here’s what that sounds like:

Sounds simple to the point of boring, right? But it’s epic, one of the main reasons music works. That second triad isn’t just a generic “away” — you can feel a magnetic pull back to home.

Let’s put it in context, melody plus harmony, with three short phrases you know. I hold the V a bit in each one so you can feel it jonesing to get home:

That’s right — Dorothy’s “can’t” has a leading tone in the melody, and a dominant in the harmony. It’s yearning for home in both ways.

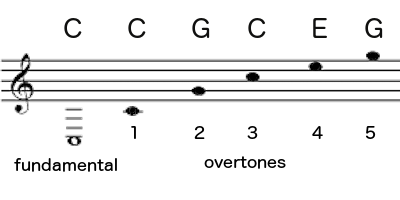

So why the special relationship between V and I? It’s the overtone series. Remember this?

In the overtone series, the fifth note of the key is the strongest pitch you hear. That’s why the fifth is the most basic pitch relationship after the octave. The G is embedded in the sound of C. Sure the leading tone is just a half step away, but emotionally, the dominant pitch is the closest thing to home. So as Western music developed its grammar, that relationship of a fifth, tonic to dominant, became the emotional center — home, and the neon arrow pointing home.

In the overtone series, the fifth note of the key is the strongest pitch you hear. That’s why the fifth is the most basic pitch relationship after the octave. The G is embedded in the sound of C. Sure the leading tone is just a half step away, but emotionally, the dominant pitch is the closest thing to home. So as Western music developed its grammar, that relationship of a fifth, tonic to dominant, became the emotional center — home, and the neon arrow pointing home.

Add the fact that the dominant chord has the leading tone in it, and you’ve got both a harmonic and a melodic magnet to home.

Composers can do wonders by promising home, then fulfilling, delaying, or denying that promise, or fulfilling it in the melody but denying it in the harmony, and on and on.

The Phillip Phillips song “Home” plays with the concept, and no surprise there. In the second verse, “Settle down, it’ll all be clear,” the harmony is on the tonic chord, but the melody floats up away from home, away from the tonic pitch:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HoRkntoHkIE” parameters=”start=45 end=61″ /]

The next phrase (“trouble it might drag you down”) could have been boringly stuck at home on the tonic in melody and harmony:

Instead, when the melody drops down to the tonic on the word down (“trouble it might drag you DOWN”), the harmony moves away from home. It’s cat and mouse:

Hear the difference? All through that verse, melody and harmony don’t find home at the same time until a strong downbeat on…what word? Yeah:

I’m gonna make this place your HOME.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HoRkntoHkIE” parameters=”start=61 end=79″ /]

Whether the composer was literally thinking of the lyric “home” and matching it with the tonic, who knows. But no decent songwriter stumbles accidentally on the home-and-away syntax of music. They know just what they want emotionally, and the home-and-away dynamic of Western harmony gives them the tools to achieve it.

The Greatest Christmas Song, in Theory

At 52, surprise is one of the best gifts I can get anymore. Ten seconds into a song on the radio — heck, five seconds — I usually know how the whole damn thing is gonna go. Same with novels, movies, news stories, even human conversations. So few surprises left.

Not good.

Kurt Vonnegut captured this in a passage about his sister Alice, an artist:

Alice, who was six feet tall and a platinum blonde, asserted one time that she could roller-skate through a great museum like the Louvre, which she had never seen and which she wasn’t all that eager to see, and which she in fact would never see, and fully appreciate every painting she passed. She said that she would be hearing these words in her head above the whir and clack of her heels on the terrazzo: “Got it, got it, got it.”

It’s a source of some despair, this receding frontier of surprise. I’d planned on a lot more music listening and book reading and movie watching before Death, which — aside from timing and method — is the least surprising thing of all.

Fortunately there are compositions, books, and movies that can still give me that experience of the unexpected, even the hundredth time I hear or read or see them. Unconventional choices keep reaching me, and I can still feel the curve as it pulls away from the easy, mundane choices that could have been made. I still get the dopamine pellet.

Christmas is the death of pleasant surprise. I love the holiday itself, but oh gawd the clichés we hang on it. The boxes in the basement might just as well be labeled “THIS AGAIN.”

Even Christmas songs that used to move me get murdered by numbing annual repetition in commercials, as sonic wallpaper in stores — even in my own living room. I used to think Carol of the Bells was this great, original thing. Now, through no fault of its own, it makes me stabby.

There are exceptions, a very few Christmas songs so well made that no amount of repetition has been able to dull my fantods. (So far, anyway — check back when I’m 72 and mainlining Conlon Nancarrow to feel something.)

Oo — that got dark fast. Just kidding about the despair, Mom! But I do find the bar for genuine surprise gets higher as you age. Music theory is my particular thing, especially harmony, so that’s where I look for the hidden gems. Finding one in a desert as trackless as Christmas music is a special thrill, and one song is exactly that gift for me — “Christmastime is Here” by Vince Guaraldi. Here’s the first verse (28 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4PzetPqepXA” parameters=”end=28″ /]

Let’s walk through the first minute of this great, great song.

After a 6-bar intro (with hints of harmony to come), the kids come in with the melody. The melody in music is like the protagonist in a story. You identify with it, follow it through the landscape of the piece. You wish it well, but not too well. Nobody wants a story where the hero never leaves the hot tub.

So here’s the hero of “Christmastime is Here” (10 sec):

Just as simple as it could be on its own.

One of the main things that “happens” to the melody in a piece is the harmony. Nothing has a greater effect on the emotional contour of the music. There are a hundred different ways to set this particular tune harmonically, and each one creates a different emotional landscape for the melody to walk through.

The first chord is the usual one — the tonic triad, the chord on the key note. We’re in F major, so it’s an F major chord. The tonic triad is the 1st, 3rd, and 5th notes of the scale, F-A-C. But as much as anything, jazz is about extending traditional concepts in music. Phrases are longer or shorter than normal, beats are divided and grouped in unusual ways, the accent is thrown to beats that are usually not emphasized.

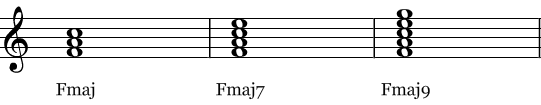

As for harmony, you don’t get too many simple triads in jazz. In addition to the scale notes 1-3-5, you’ll often get an added 7, sometimes 9, sometimes more. It makes a more complex sound:

When the melody comes in, Guaraldi puts the first measure (“Christmas time is”) over Fmaj7. That’s jazzy, but it also runs the risk of sounding hokey. A lot depends on the next chord (when the kids sing “here”). He could just keep the F chord — it fits with the melody just fine — then move to the usual suspects after 4 bars. After the F chord, C is the most likely chord you’ll hear (more on that in the next post). B-flat is next after that. These aren’t bad choices, just…predictable. Sometimes that’s what you’re going for: Silent Night in the key of F uses three chords: F, C, and B-flat.

Here’s what “Christmastime” could have sounded like if Guaraldi phoned it in:

It isn’t terrible, but it also has no surprise.

Guaraldi took the road less traveled. Not only does he not choose one of the usuals for the second chord, he doesn’t even choose a chord that’s in the flippin’ key. The chord he chose is a warm, luscious, unexpected Eb#11. It’s unexpected, but it isn’t wacky, and it’s as smooth as a baby’s bootay. The reason for that is something called voice-leading: The new chord is on another harmonic planet, but every note was arrived at by a single step from a note in the previous chord.

Here it is, stripped of drums and kids:

There’s so much more — for extra credit, you music theorists can find the B half-diminished 7th and Gb#11 (‽), both of them bootay-smooth from voice-leading — but Christmastime is here, so it’s time to close the computer.

Not you! First enjoy the whole thing without the adorably out-of-tune kids. Merry Christmas.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4PzetPqepXA” /]

No One Owns the Worst Song in the World

- December 10, 2015

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined

0

0

A U.S. District Court judge recently ruled that Warner/Chappell Music Inc. doesn’t own the song Happy Birthday after all. They’ve been earning $2 million a year in royalties for it, mostly for film and TV use. Remember the Friends episode where the waiters gathered around the table to sing Happy Birthday to Joey even though it was Phoebe’s birthday? That cost the show five grand, easy.

The gravy train is over for Warner/Chappell. The suffering continues for the rest of us. “Happy Birthday” is just about the worst song in the world.

It isn’t just the song itself. There’s also the painful, untextured ritual of it, year after year, party after party, unvaried but for the occasional loveless insertion of cha-cha-cha. It is a bit of mummery that brings joy to exactly no one, ever. It’s a thing we do because it is done. And every time we sing it, 15 seconds drop through the drain at our feet, never to be recovered.

Happy Birthday.

So the bland ritual is bad, but so is the actual song. Start with the words. Imagine what we could say to each other every year! We could have a song that reminds us what a birthday really is:

Once again the earth comes ’round

To where you came to be

And now we celebrate before

You’re snuffed by entropy.

Okay, a work in progress. But “Happy Birthday to you” four times? That’s just phoning it in.

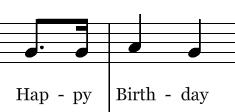

Speaking of which, the first notes of the melody include one of the most boring possible melodic structures:

The note on “Birth” is called a neighbor tone. Start on a note that’s in the chord, go up (or down) one step, then back to the first note again. That’s a neighbor. Now add the fact that this particular one goes up to the sixth note of the major scale, the absolutely least interesting pitch in the scale, and you have the musical equivalent of lifting your head from the pillow for a moment before laying it down again.

After an admittedly cool accented passing tone on the first syllable of the birthday kid’s name — you get a tritone with the bass if harmony is playing, very nice — time begins to stretch:

Happy Birthday Dear Miiiiiiikeeeeeeeey…

We draw the name out in a rallentando, then hang a big caesura (a hold) over the last syllable. Why? We’ve been singing for all of eight seconds, I don’t need to rest. Yes, drawing out their name makes the kid feel special…but tick tick, you know? I say keep the tempo steady, save three seconds each time, and hike Denali with the time you accrue over the years.

Okay, I’ve dissed the Star-Spangled Banner and Happy Birthday. Next time I’ll go after Amazing Grace.

Photo by Omer Wazir | CC 2.0

Song Breaking Your Heart? It’s (Mostly) Not the Words

When I was teaching freshman theory, I’d ask my students to bring in recordings of music they liked. Always my favorite part of the class. I’d ask what was going on in the music, what was making the emotion happen. And for the first few days of the year, they’d almost always say the same thing.

It’s the words, they’d say. The lyrics make it sad or angry or happy. It’s those words.

Yeah, it’s not the words. Mostly not, anyway.

I adore great lyrics. I can rattle off a dozen songs with lyrics that move me deeply — but they’re rarely the primary engine driving the emotion. Take the most heartbreaking song you know. Keep the lyrics the same, put polka music under them, and watch what happens to the emotion.

Now go the other way — keep the music the same and change the lyrics to la la la. In most cases, it’ll still break your heart.

Here are some dark, nihilistic lyrics for you:

I’m getting bored being part of mankind

There’s not a lot to do no more

This race is a waste of time

People rushing everywhere, swarming ’round like flies

Think I’ll buy a .44

Give ’em all a surpriseThink I’m gonna kill myself

Now watch Elton John mess with you:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/82wU5NfRfr4″ /]

Lyrics are emotional icing. The actual music, especially the harmony, is the cake. The next few posts will explore why and how.

The (Actual) Evolution of Cool

- October 30, 2015

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined, Unweaving

0

0

Tower of Power was my band in high school. One reason was the insanely tight horn section, including SNL frontman Lenny Pickett. But another was the music itself.

It was cool.

I was also a marching band guy, and I always liked me some Sousa marches, though not for the same reasons I liked Tower. Sousa has horns, and they might be tight, but nobody would call “Stars and Stripes Forever” cool. Strong maybe, proud, confident, celebratory — but cool doesn’t enter into it.

Doesn’t matter if you like a piece of music or not. I hate certain kinds of jazz, for example, while still recognizing that they exist in the wheelhouse of “cool.” And I’ve always wondered what accounts for that instantly recognizable quality.

Now I think I’ve found it.

A few posts ago I mentioned a hideously wrongheaded passage about dissonance from the book This is Your Brain on Music by Daniel Levitin. The rest of the book was entirely rightheaded — and one section in particular blew my mind.

I double-majored in music and physical anthropology, so any time I trip over a credible link between music and evolution, there is much rejoicing. In one chapter, Levitin explores a fascinating function of the cerebellum that crosses that very bridge: timekeeping.

The cerebellum is one of the oldest structures in the brain, so any adaptive features located there are likely to have deep evolutionary advantages. They are likely, in other words, to benefit not only humans, but the common ancestors we share with a whole lot of other creatures.

The cerebellum is mostly about coordinating movement, but researchers have also found it getting busy when we listen to music. Long story short, it seems to correlate to the pleasure (or lack) that we get from the rhythm in a song. As a Salon article a few years back put it,

When a song begins, Levitin says, the cerebellum, which keeps time in the brain, “synchronizes” itself to the beat. Part of the pleasure we find in music is the result of something like a guessing game that the brain then plays with itself as the beat continues. The cerebellum attempts to predict where beats will occur. Music sounds exciting when our brains guess the right beat, but a song becomes really interesting when it violates the expectation in some surprising way — what Levitin calls “a sort of musical joke that we’re all in on.” Music, Levitin writes, “breathes, speeds up, and slows down just as the real world does, and our cerebellum finds pleasure in adjusting itself to stay synchronized.”

That’s great. But why would this ability have evolved? Why does evolution care what music you like?

Honey…evolution doesn’t give a damn about you personally, much less what kind of music makes your weenie wiggle. But on the population and species level, it does tend to favor abilities that keep an organism alive a little longer. One of those is the ability to detect small changes in the environment, because change can indicate danger. Here’s Levitin:

Our visual system, while endowed with a capacity to see millions of colors and to see in the dark when illumination is as dim as one photon in a million, is most sensitive to sudden change….We’ve all had the experience of an insect landing on our neck and we instinctively slap it—our touch system noticed an extremely subtle change in pressure on our skin….But sounds typically trigger the greatest startle reactions. A sudden noise causes us to jump out of our seats, to turn out heads, to duck, or to cover our ears.

The auditory startle is the fastest and arguably the most important of our startle responses. This makes sense: In the world we live in, surrounded by a blanket of atmosphere, the sudden movement of an object—particularly a large one—causes an air disturbance. This movement of air molecules is perceived by us as sound….

Related to the startle reflex, and to the auditory system’s exquisite sensitivity to change, is the habituation circuit. If your refrigerator has a hum, you get so used to it that you no longer notice it—that is habituation. A rat sleeping in his hole in the ground hears a loud noise above. This could be the footstep of a predator, and he should rightly startle. But it could also be the sound of a branch blowing in the wind, hitting the ground above him more or less rhythmically. If, after one or two dozen taps of the branch against the roof of his house, he finds he is in no danger, he should ignore these sounds, realizing that they are no threat. If the intensity or frequency should change, this indicates that environmental conditions have changed and that he should start to notice….Habituation is an important and necessary process to separate the threatening from the nonthreatening. The cerebellum acts as something of a timekeeper.

Our cerebellar timekeeper determines how regular a sound is. If it stays predictable — dripping water, chirping crickets — we feel confident and secure. If it becomes less predictable or changes in intensity, we feel unsettled, possibly threatened.

Listen:

The Thunderer, John Philip Sousa

The beats are regular. Your cerebellum is tapping its foot, predicting every beat, right on the money. It makes you feel safe, confident, in control. It’s a great performance of a great march, but no one would call it cool.

Then there’s this…hold me…

“Sacrificial Dance” from The Rite of Spring, Igor Stravinsky

In addition to intense dissonance, it’s jerky and angular, with completely unpredictable rhythms and sudden changes in intensity — the musical embodiment of anxiety and terror. And it bloody well should be — a sacrificial virgin is dancing herself to death on a fire, for God’s sake. Your cerebellum is freaked out by the utter inability to predict the next note. The music is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do, but you wouldn’t call it cool.

The music we usually identify as cool splits the difference, combining a steady predictable beat with unpredictable departures from that beat. It’s flirting with the remote sense of danger without actually endangering you. Once again, a rollercoaster analogy works perfectly: the feeling of being tossed around without actually getting killed can be thrilling.

If music establishes a beat, then throws you around a bit — backbeat accents, unexpected hits around the beat, changing patterns — it gives a little thrill to your cerebellar timekeeper, tickling that part of you that listens for the irregular sounds of danger, then pulling you back to the safety of a steady beat before dangling you over the cliff again.

Let’s all agree that “Superstition” by Stevie Wonder is cool. Listen to how the drums set a metronome-steady beat for the first 10 seconds. Then that funky clavinet comes in, a mix of on-beat and jerky staccato syncopations. By the time the horns are in, we have layers of offbeat counterpoint dancing around the steady beat, this complicated tapestry of sound:

In the end, the proof is in the ruining. If you want to strip all of the cool out of a cool song, make it safe. Take every unpredictable syncopation and put it on the beat, like every middle school arrangement of every popular song:

Dude. Not cool.

Bonus cool: My favorite song in high school

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

The Case Against the Star-Spangled Banner

- October 13, 2015

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined

0

0

It’s a waltz, for starters. Nobody else has a national anthem that’s a waltz. Okay, there’s “God Save the Queen,” but that’s it. The rest are proper marches or noble hymns, not prancy little dance ditties.

Lemme start over.

Every once in a while, someone in Congress introduces a bill to replace the current US national anthem, usually based on its militarism or unsingability.

The case against the Star-Spangled Banner starts there, but there’s much more wrong with our national song. By the end of this post, I hope you’ll join me in writing your representatives so the bill can be raised and defeated yet again.

Here are nine reasons to be all-done with The Star-Spangled Banner.

1. It’s militaristic.

Well it is. Why sing about rockets and bombs when we could celebrate spacious skies and amber waves? Not that I have any particular replacement in mind.

Granted, the militarism of the SSB pales in comparison to the most bloodthirsty national anthem on Earth, “La Marseillaise” (shudder). While it’s musically magnifique, the French anthem is a festival of rage and gore, including throat-cutting, watering the furrows of the Homeland with the impure blood of enemies, and the children of France yearning to join their ancestors in their coffins.

Ours celebrates surviving an assault, not slaughtering the foe, I’ll give it that. So it’s not as militaristic as La Marseillaise, which is like not being as rude as Stalin.

2. It’s unsingable.

The range is too wide – an octave and a fifth, from middle B-flat (on “say”) to very-high F (on “glare” and “free”). That’s why ballpark wise guys do a falsetto yodel up to double-high B-flat on “land of the freeee” – to give the impression that they really could have held that F without cracking, but they’re just, you know, messin’ around.

3. The War of 1812…Seriously?

Francis Scott Key’s poem “The Star-Spangled Banner” commemorates the siege of Fort McHenry during that most heart-poundingly memorable of our national military conflicts, the War of 1812. Who could ever forget the Chesapeake-Leopard incident, the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the traitorous clamor of the Hartford Convention…

Look, it was an odd war. The British had been boarding our ships looking for deserters, and we asked them to stop. They wouldn’t, so we declared a war that ended three years later in a draw. Not really the stuff of anthems, in my humble. (And the 1812 Overture, by the way, our 4th of July favorite, doesn’t have anything to do with the War of 1812. It was written by a Russian to commemorate the forced retreat of Napoleon from Moscow. But that’s a separate facepalmer.)

4. It’s not militaristic enough.

If you’re going to write about an artillery bombardment, bring it. Instead, right when we’re singing about rockets and bombs, the band goes quiet and shifts to the woodwinds. Here’s the US Marine Band depicting a naval assault (16 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R39e5dOc7AU” parameters=”start=34 end=50″ /]

The music here doesn’t fit the text. This spot is not technically the fault of the song itself, but it’s woven so deep into the arrangement tradition by now that I’ll sustain the objection.

5. “Bombs bursting” can hardly be said, much less sung.

Ever notice that the crisp dotted eighth-sixteenth of the first stanza (O-o say and By the dawn’s) gets ironed out to two eighth notes in the middle of the verse? Sometimes you still get the dotted rhythm for And the rock-, but no one has tried to sing The bombs burst- in a dotted rhythm since the mass lip-mangling incident at Game 3 of the 1937 World Series. You may have noticed that ambulances now attend every sporting event where the National Anthem is sung, just in case someone tries it again.

6. Did I mention it’s a waltz?

Music with beats in groups of two or four can be many things – moving (America the Beautiful); peaceful (Pachelbel’s Canon); stirring (The Marseillaise); sensuous (Girl from Ipanema); or even an electrifying thrill ride (The Macarena). But waltz time just goes oom-pa-pa.

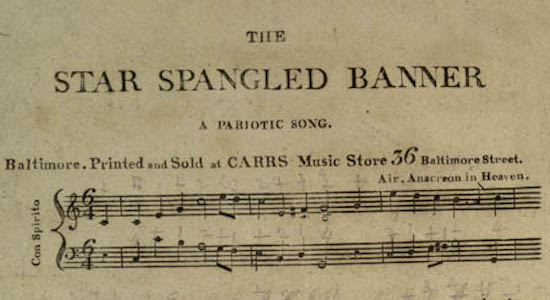

7. The tune is English.

Who were we fighting in 1812? The hated Costa Ricans? The dreaded Laplanders? No, it was the English. So when we dug into our repertoire for a tune that matched the metrical structure of the poem Francis Scott Key had written commemorating our victory over the English, we chose “To Anacreon in Heaven” – an English drinking song.

8. IT’S A DRINKING SONG.

“To Anacreon in Heaven” was written in London in the 1770s by members of the Anacreontic Society, an upper class men’s club that met at the Crown and Anchor Tavern to sing the praises of…well, let’s just see. Here’s the first verse of the lyrics – you know the tune:

To Anacreon, in Heav’n, where he sat in full glee,

A few sons of harmony sent a petition,

That he their inspirer and patron would be,

When this answer arrived from the jolly old Grecian –Voice, fiddle and flute, no longer be mute,

I’ll lend ye my name, and inspire ye to boot…

And, besides, I’ll instruct ye, like me, to entwine,

The myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s vine.

So Anacreon, a Greek lyric poet of the 6th century BCE, approves the use of his name and instructs the “sons of harmony” to “entwine the myrtle of Venus” – the goddess of love – “with Bacchus’s vine” – the god of wine. He tells them, in short, to have drunken sex.

In subsequent verses, Zeus is made furious by the news of the proposed entwining, convinced that the goddesses will abandon Olympus in order to have sex with wasted mortals, and dispatches Apollo to stop it. But Apollo is laid low with diarrhea and, fleeing his citadel with his “nine fusty maids,” is rendered unable to countermand the order.

I couldn’t make this stuff up on my best day.

Yes, the tune had other lives in the intervening years. It was exported to the United States as early as 1798 and reset to various lyrics, including that old toe-tapper “Adams and Liberty.” But don’t you think the original setting kind of, I don’t know – adheres a bit? No matter how much time passes, I don’t expect “I Like Big Butts” to ever give rise to a hymn tune, no matter what other incarnations it has between now and then.

9. It’s not sacred. In fact, we did without a national anthem for over 150 years.

Though Key’s poem “The Star-Spangled Banner” was around from 1814 and even got the tune stuck to it shortly thereafter (as a spritely dance), it wasn’t adopted as the national anthem until 1931. This ancient, venerable tradition was born the same year as my dad. Prior to that it was just another national song, on par with “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and “Hey Nonnie Noo, I’m a Yankee Too!”, which doesn’t even exist. Before that, the United States of America had no official national anthem. Even Estonia beat the pants off us. They got their anthem in 1869 – and not from a barroom floor, I’ll bet.

So why not give an aggressive, unsingable, recently-adopted, ill-constructed waltz-time descendant of a raunchy bar ballad turned celebration of obscure military stalemate the heave-ho?

Because it’s tradition, silly.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/3l-n64NWHS4″ /]