The Hidden Grammar of Music

I was 13 when I saw my brother’s college music theory textbook sitting on a table — Walter Piston’s Harmony. I had played clarinet and sax for a while, even did some arranging for jazz band. So I knew a little theory, but I was barely out of the blocks.

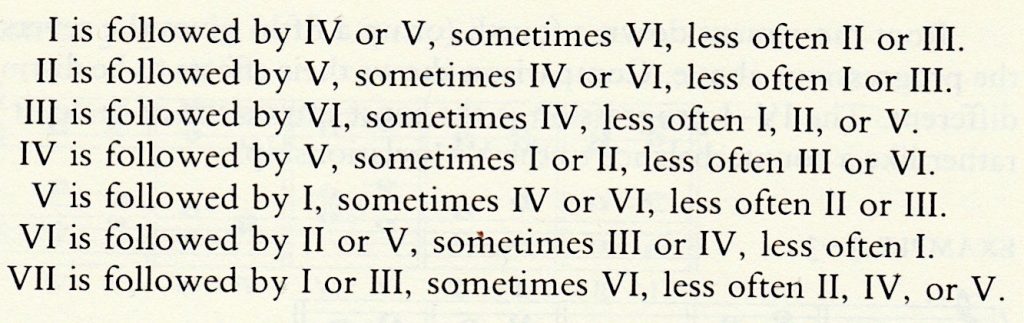

When I picked up the book, it fell open to a section called “Table of Usual Root Progressions.” Clickbait! I traced the words with a trembling finger:

Whoa.

If I’d known less theory, I’d have glossed right over it without understanding what it meant. If I had known more, I might not have been surprised by it. As it happens, I knew just the right amount to be gobsmacked.

It continued:

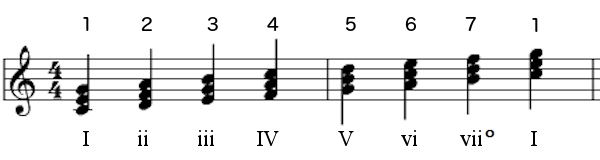

Here’s what it’s saying. Every key has 7 triads in it — 7 chords based on the 7 notes of the scale for that key. This is C major:

Now look down the left side of the Piston text: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII. These are the 7 triads of any key. (If you know some theory or read this post, you’ll know the Romans are usually upper case for major and lower case for minor. He’s making them generic for this example. Be not confused.) Each line is saying, “When you hear this chord, here are the chords you’ll most likely hear next.”

So for C major, you could rewrite the text like so:

The C triad is followed by F or G, sometimes A minor, less often D minor or E minor.

The D minor triad is followed by G, sometimes F or A minor, less often C or E minor.

And so on.

Here’s the thing: I had no idea there was a “most likely” order of chords. If I’d written a theory book when I was 13, it would have said

Chords are nice because they make the music fuller than just a tune alone. If you’re in the key of C major, the C triad should be followed by something different, because variety is the spice of life. GENESIS RULES! DM + KH 4EVER

I saw the chords as 7 different colors the composer could use, and yes, they are that. But it never occurred to me that there was this kind of hidden sense to it, a kind of grammar, like saying The subject is usually followed by a verb, sometimes by an adverb, less often by a prepositional phrase.

It was my first real glimpse below the surface of music. And then Piston did something lovely and rare in music theory — he explained why it’s that way.

When you move from any triad to another, there are only three possibilities: the chords have two shared notes, or only one, or none at all: Each of these has a different emotional quality. The first one is called a “weak” progression (though never to its face) because there’s only that small change between the chords, just one note different while two hang on. It’s like a sloth working its way through the forest canopy, moving just one limb at a time while the others stay attached.

Each of these has a different emotional quality. The first one is called a “weak” progression (though never to its face) because there’s only that small change between the chords, just one note different while two hang on. It’s like a sloth working its way through the forest canopy, moving just one limb at a time while the others stay attached.

When the roots of the chords (the note on which it is built) are a third apart, like C to E, you get that progression.

“Weak” doesn’t mean bad — sometimes a weak progression is just what you want for a tender moment, like so:

Here it is put to perfect use:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/J6xzL0TrsRY” parameters=”start=67 end=78″ /]

If all of the notes change, the feeling is more abrupt. There’s no connection between the chords. There isn’t a sense of smooth harmonic direction because the connection to the previous chord isn’t there. It’s a monkey leaping from one tree to another. You can’t easily tell where he leapt from.

When the roots of a chord are a second apart, like C to D, you get this kind of progression. The chord change at 0:38 is this type:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/eQAm7eZr920″ parameters=”start=17 end=45″ /]

And then there’s the engine that drives music. This is for chords with roots a fifth apart, like G and C, dominant to tonic. It’s Goldilocks, not too weak, not too abrupt: one note shared, two notes changing. It’s the perfect balance of continuity and dynamism, the monkey brachiating effortlessly through the rainforest of your mind, one hand back on the previous branch, a hand and a foot reaching forward to the next. And on he swings.

It’s called a circle progression for a great reason I’ll get to eventually.

When a composer wants you to feel direction on a large or small scale, the circle progression is the go-to. It flows like water. This aria from a Bach cantata is as good an example as any. The circle starts at 0:17 and ends around 0:30.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/3rKIc6QBCig” parameters=”end=31″ /]

Do you feel how the harmony was essentially marking time at the beginning, then starts rolling forward at 0:17? Circle progressions will do that to you.

The big news here is that harmony is spinning out a narrative beneath the melody. Composers use a mix of the three types of progressions to create an ebb and flow — moving forward, circling back, pausing, lurching, and sliding effortlessly in turn.

Now if you look back at the Piston text, it starts to make sense. No matter which of the 7 chords you’re on at a given moment, the most likely next step is a circle. That Bach progression is

I – IV – VII – III – VI – II – V – I

That’s all circle, and you can feel the tumbling momentum. But sometimes you don’t want that, so you’ll move by second or third, depending on the musical need of the moment.

Like all grammars, the real fun comes in busting out of the box — chromatic harmony, secondaries, modal harmony, polytonality, atonality, jazz harmony — but that page of Piston’s Harmony was my first step into the basic grammar of Western music. And it totally changed the way I saw my favorite thing.

Follow me on Facebook:

What Happens When “Happy” Goes Minor?

- November 06, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined

0

0

Major is happy, minor is sad. It’s the one music theory thing that everybody knows. But what happens when you cross the streams, taking a major song and throwing it into the soul-crushing abyss of a minor key?

That’s just what Chase Holfelder’s Major to Minor project does, turning upbeat numbers like “Kiss the Girl” from The Little Mermaid into a creepy assault fantasy, and making the sweet tribute to undying love that is “I Will Always Love You” into a soundtrack of dark obsession (20 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/_xz10ZNNkoM” parameters=”start=113 end=134″ /]

But there’s one pretty obvious target that Chase hasn’t transmogrified yet — a song so happy that its actual name is “Happy.” So I wonder what happens if you take Pharrell Williams’s infectiously danceable hit and put it in a minor key?

I’ll tell you what happens. NOTHING happens — because “Happy” is already in minor.

[arve url=”https://giphy.com/embed/g1a84q6RBSMrS” /]

You don’t believe me OR Anna Kendrick? Fine. First a taste of the original, then I’ll wreck it to prove my point (24 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y6Sxv-sUYtM” parameters=”start=11 end=36″ /]

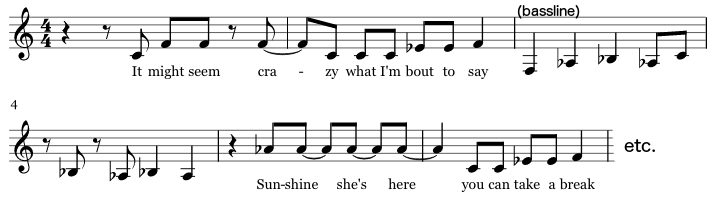

If you read music, you can see it on the page. The F minor scale has Ab, Db, and Eb — F major does not:

Straight up F minor.

Now there is a little major cream in the minor coffee of this song, a few A-naturals peeking through here and there. It’s a common practice in jazz and R&B to let major and minor knock up against each other. But there’s no doubt that minor wears the pants in this one. If I scrubbed every little fleck of major from “Happy,” turning it all minor, you’d hardly notice the difference. Turn it all major, though, and the song is destroyed.

Lemme crank up my quaint Korg M-1 to do a reverse Holfelder, switching “Happy” from minor to major. Here’s the opening:

Gah. It’s like the Partridge Family at its whitest.

Even worse is what happens to this spot, where the backup singers sing “Happy, happy, happy, happy…” (12 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y6Sxv-sUYtM” parameters=”start=121 end=132″ /]

Here it is in F major:

Okay, so “Happy” is minor. But how can that be? How can anything as happy as “Happy” be in a minor key?

The answer is that emotion in music isn’t on a simple major/minor toggle. A lot of variables are in play. In his remixes, Holfelder never only changes the mode to minor — he messes with tempo, instrumentation, dynamics, vocal stylings, and chord structures as well.

This goes both ways: By fiddling with other switches, music in a major key can be just as sad as minor. This devastating number from Les Miz is in a major key:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/86lczf7Bou8″ /]

And aside from sad, a minor key can be powerful, goofy, thrilling…and yes, even happy.

Don’t miss a post! Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

The Masterpiece I’d Never Heard Of

During the 2016 US presidential campaign, Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson was asked on national television what he would do about Aleppo as president. When he said, “And what is Aleppo?” my heart lurched. And when the interviewer said, “You’re kidding,” then spelled out the centrality of Aleppo to the crisis in Syria as if Johnson had revealed himself to be a small, dim child, my lurched heart collapsed like a dying star.

It took me back to a moment in my doctoral program when I sat with five other candidates for the Ph.D. in music in the withering glare of an astonished professor. She was a brilliant composer with an encyclopedic grasp of All Human Knowledge, or so it constantly seemed, and a mission to ferret out the ignorance of others, often publicly, with unforgettable shock and zeal. And hey, a Ph.D. represents a capstone endorsement of mastery in a given field, so such ferreting is not without purpose. But she felt that subject mastery should be accompanied by general mastery. Again, I agree — brilliance in one field accompanied by ignorance in most others isn’t a great educational outcome. But there are side effects of this kind of prolonged trial by fire, and for many years afterward, I struggled to shake a really bad habit: the inability to admit that I didn’t know something. ANYTHING.

Back to the withering glare, which was deployed when she realized that none of us knew the name H.L. Mencken.

I later discovered Mencken and became a great admirer. But when she read a Mencken quote in the seminar, the name rang no bells. Sensing this, she said, “And H.L. Mencken is, of course…?”, I sat in silent, rising horror with my classmates, knowing what would come.

A gasp.

“H.L. Mencken??”

Her eyes inflated and met each of ours in dramatic turn. Another gasp.

“H.L. Mencken H.L. MENCKEN???”

“A writer?” someone guessed desperately.

“American or British? American or British???”

“Uh…American?”

“Critically. Important. Influential. Early. 20th. Century. American. Journalist. And. Satirist. H. L. Mencken.” She exhaled in disgust. “You should know H.L. Mencken.”

But we didn’t. And worse, now she knew we didn’t.

In addition to good things, grad school is an extended exercise in hiding what you don’t know. You first learn to hide it from those who hold your future in their hands, then quickly generalize the habit to all humans. When someone asks a grad student in music if he or she is familiar with a certain composer, performer, conductor, stylistic movement, or piece — or in this professor’s case, writer or activist or medieval Estonian peasant revolt — the graduate student will answer with some version of, “Yes, of course.” Every time.

If the student actually knows it, you might detect this slightly enthusiastic leaning-forward, an eagerness to share. If he or she has never heard of it, the “Yes, of course” will be accompanied by a facial expression that says, “I seem to have swallowed a cockroach.”

S/he’s worried that the thing in question might be so well known to the asker that saying “Never heard of it” will seem as bad as if the question had been, “Are you familiar with the letter E?”

Next time you’re around a grad student in music, say, “I just adore the late quartets of Johann Mamflamheim, don’t you?” When s/he says, “Yes, of course,” ask which one is his or her favorite and why. Real entertainment ensues. The game is adaptable to all fields of study.

This professor lived for that kind of reveal.

The oral preliminary exam near the end of a Ph.D. program is the culmination of this dynamic. You sit around a table with your doctoral committee — usually 4 or 5 graduate faculty members — and they grill you unsmilingly for two hours. The purpose is to test the comprehensiveness of your knowledge of the field. If you fail to demonstrate sufficient mastery, in their sole judgment, you are dismissed from the doctoral program and may not re-apply.

My Ph.D. area was music composition. A year before the oral prelims, I asked my grad advisor what I could expect. “It’s not pleasant,” he said. “That’s by design. They will try very hard to rattle you. They want to reveal what you don’t know and see how you handle that.”

Mm. “Should I expect theory too, or just composition?”

He looked at me over his glasses. “The subject is music. Music as a human endeavor in all places and times. Absolutely everything is game.”

I spent that year in intensive gap-filling. I scoured the Harvard Dictionary of Music for unfamiliar terms. I refreshed my knowledge of medieval modal theory. I listened to hundreds of hours of music in every culture and genre. Classical, jazz, Balinese gamelan, Indian carnatic microtonal singing, shape note singing, Tuvan throat song, and the insane piano rolls of Conlon Nancarrow. I read histories and analyses and theory journals.

Two days before the exam, riffling through some journal, I saw a passing reference to a piece called The Infernal Machine, written by Christopher Rouse in 1981. An example of the mechanistic movement of composition in the late 20th century, in which musical instruments were used to evoke machinery. I’d never heard of the piece, the composer, or the stylistic movement.

I filed the information in my head.

Two days later I was sitting before the committee, waiting for the first question.

“I’ll begin,” said the Formidable One. “Mr. McGowan, what can you tell me about the mechanistic movement of composition?”

I am not kidding. I nearly passed out.

“The mechanistic movement,” I said steadily, “was a late 20th century experiment in which musical instruments were used to evoke the sounds of machinery.”

“Excellent,” she said. “Name a representative composer.”

“Well there’s Christopher Rouse, of course.”

“Of course. And a piece by Rouse that can be rightly called mechanistic?”

“The Infernal Machine.”

“Excellent!” She was determined to find the edge of my abyss so she could place her fingertips on my chest and shove. “And the year The Infernal Machine was composed?”

I paused, pretending to search deep in my files for what was actually still on a Post-It note flapping perilously in the breeze on my prefrontal cortex. “I believe that was…1981.”

She slammed a hand on the table. “Yes! Excellent!”

This is not a story of celebration, you understand, not even slightly a brag. This was stupid luck, a bullet dodged. I can only guess how the rest of the prelim would have gone had I whiffed the first pitch. The nature of such exams is to build a mighty snowball around any small core of found weakness, which underlines the basic lunacy of the assumption that a person can be in full possession of knowledge, even in one field of specialization, Herself excepted.

Fast forward to now. I’m reading a great book called Listen to This by Alex Ross, music critic for the New Yorker, a collection of essays about music covering an amazing range of topics from Schubert to Radiohead.

In the Radiohead chapter, guitarist Jonny Greenwood is quoted as saying “I heard [Olivier Messiaen’s] ‘Turangalîla Symphonie’ when I was fifteen, and I became round-the-bend obsessed with it.” That kind of thing is always fun, like finding out Yo Yo Ma loves bluegrass.

Twenty pages later, in a chapter on the Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen (yep, say it out loud, I’ll wait: ), we get this:

It was the experience of hearing Messiaen’s sublimely over-the-top Turangalîla, at the age of ten or eleven, that inflamed his desire to compose.

Well that’s funny. Two very different musicians had their minds nicely blown by Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphonie before they could drive.

Oh, and here’s an interesting thing about the Turangalîla Symphonie: I’D NEVER HEARD OF IT. I didn’t even know much about the composer, and I certainly would have remembered the name of that piece.

I have a thousand files in my head with information about music. The J.S. Bach file has bio on the surface, then continues down through elements of style (and why), favored genres (and why), impact on the course of European music including specific influence on key composers of the following generations, and a thoroughgoing catalog of works, including an ability to sketch the full 32-movement structure and harmony of the Goldberg Variations on the back of a napkin after three pints. I could pick out his handwritten music notation from a lineup. I ran the whole C minor Passacaglia through my head as I sat in the Thomaskirche where he worked and is buried. I know Bach and a hundred others inside and out.

But my Messiaen file looks like this:

MESSIAEN, OLIVIER (sp?)

French composer, 1940s. Catholic. Wrote ‘Quartet for the end of time,” a lot of long notes. Liked birds.

On one level, the details are trivial. They aren’t what ultimately makes for mastery. But they are the brown M&Ms of knowledge: If those surface details are wrong or missing, it probably indicates rot down below.

If the Formidable One had asked me to name any two pieces by Messiaen, I’d have been screwed. But here were two musicians of very different traditions who had come across and been deeply influenced by a massive orchestral piece of his that I’d never even heard of, even after completing a Ph.D. in composition and teaching music history at the college level for 11 years. And they knew it when they were 10 and 15.

But here’s the thing: after years of recovery, I’m apparently okay with that. Until now, I’d never heard of it. There, I said it out loud. Never heard of it.

If you find yourself in possession of 80 minutes and a sense of adventure, here’s the massive, weird rollercoaster of the Turangalîla Symphonie by Olivier Messiaen.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PjyCpRKDrk” /]

Even for Messiaen, the Turangalîla-Symphony is weird. Rather than the usual rapt mixture of birdsong, plainchant and Catholic theology, here we have dancing rhythms, tantric sex and laughing gas. — Phil Kline

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Why is That iPhone “Don’t Blink” Ad So Damn Cool?

I don’t care about the headphone jack. Listen to the music:

Almost every part of the ad score is variations on a single rhythm — that Bump. Bump. Bump, bump, a-CHAK you hear in the opening seconds. It’s a cool rhythm. But what’s cool about it?

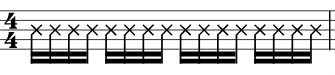

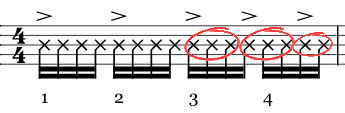

It’s not pitch. This is mostly about rhythm, the division of time into bits. If you have four beats per bar and divide each of them into four 16th notes, you can think of the bar as having 16 available slots. In each one, you have a choice: hit the drum, or hit it hard (accented), or do nothing. 16 slots, 16 choices in each bar:

Just as melody and harmony draw on 12 available pitches, most rhythm (in 4/4, the most common meter) is created from grouping these 16 clicks. In this case, it’s 4+4+3+3+2:

1234 1234 123 123 12

Two groups of 4, then two groups of 3, then a group of 2. This has the effect of establishing a steady beat (1234 1234), then throwing you off balance a bit (123 123 12), then returning to steady in the next bar (1234 1234). On top of that, there’s a feeling of acceleration as the groups get shorter.

The combined result is two confident steps, then trip-tumble forward a little, then a smooth recovery into the next measure.

Okay, bad example. More like this:

We’ve been here before, in the post on The Evolution of Cool:

Our cerebellar timekeeper determines how regular a sound is. If it stays predictable — dripping water, chirping crickets — we feel confident and secure. If it becomes less predictable or changes in intensity, we feel unsettled, possibly threatened.

The beats [of a Sousa march] are regular. Your cerebellum is tapping its foot, predicting every beat, right on the money. It makes you feel safe, confident, in control, but no one would call it cool.

The Sacrificial Dance from The Rite of Spring is jerky and angular, with unpredictable rhythms and sudden changes in intensity — the musical embodiment of anxiety and terror. Your cerebellum is freaked out by the utter inability to predict the next note. The music is doing what it’s supposed to do, but you wouldn’t call it cool.

The music we identify as cool splits the difference, combining a steady predictable beat with unpredictable departures from that beat. It’s flirting with the remote sense of danger without actually endangering you.

If music establishes a beat, then throws you around a bit — backbeat accents, unexpected hits around the beat, changing patterns — it gives a little thrill to your cerebellar timekeeper, tickling that part of you that listens for the irregular sounds of danger, then pulling you back to the safety of a steady beat before dangling you over the cliff again.

The ad throws a few extra stumbles in to keep you off balance on the larger scale. Start tapping right at the beginning and keep it rock steady. You’ll feel yourself trip over a notch in time around 4 seconds:

Feel that?? One extra 16th rest was inserted, a single click in time, throwing you behind the beat. That gives your cerebellar timekeeper a little thrill. That’s cool.

Yeeeah, Something’s Gonna Harm You – Sweeney Todd

5 min

Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd just reappeared on Netflix streaming, and within two days I had a reader question about it:

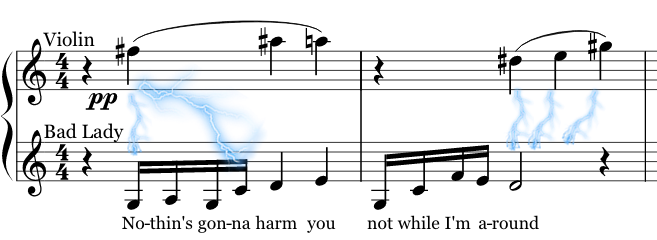

Q: In Sweeney Todd, at the end of the scene where Toby sings Nothing’s Gonna Harm You to Mrs. Lovett, she sings it back to him, but the music is suddenly making my flesh crawl when she does. What the heck is going on?? – Wendy T.

Oh Wendy. I know the scene.

The music in Sweeney Todd is phenomenal and the lyrics among the most inventive Sondheim ever wrote. And that’s saying something for the guy who came up with

I like the isle of Manhattan

Smoke on your pipe and put that in

THE SCENE: Little Toby has realized Mr. Todd is up to no good, and he’s worried about Mrs. Lovett, without whom he’d be living in a Dickens novel — and not the What-day-is-it-today, delightful-boy, bring-me-that-goose-and-I’ll-give-you-a-shilling part.

Toby sings “Nothing’s gonna harm you / Not while I’m around” to a trite melody that mirrors his naiveté. We know something that Toby does not: Mrs. Lovett is a willing accessory to Sweeney Todd’s crimes, guilty right up to her meat pies.

While Sweeney has been driven to a murderous spree by a missed chance to kill the judge who ruined his life, Mrs. Lovett is only in it for the filling. So when Toby goes all Oliver Twist on her, you can see her soften a little.

Mid-scene, Toby sees something that confirms his suspicions about Mr. Todd — the coin purse of his missing and presumed-dead master — and he flips out. To calm him, Mrs. Lovett sits him down and sings the same protective song that Toby sang to her. But we know, from the music alone, that she has decided to kill the boy.

Watch the whole scene for the full effect. The skin-crawl starts at 2:48:

3:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/LssWKaDF9bk” /]

What’s Going On

The music is identical to Toby’s song with one addition: a quiet violin line high above the voice. While Mrs. Lovett is singing in C major, the violin is playing an atonal melody, meaning the notes don’t really fit into any key — the musical equivalent of insanity. As a bonus, the particular notes he chose are creating strong dissonances with the melody — ninths, sevenths, tritones.

Sondheim doesn’t need to hit you over the head — just six quiet disordered notes tell you how different Mrs. Lovett’s thoughts are from her words. If the lines were in the same octave, it would be harsh and unsubtle. By instead putting two octaves of air between them, Sondheim makes your skin crawl.

Is there a piece of music you love or hate but don’t know exactly why? A moment that makes you laugh or cry? Be like Wendy. Submit a question here!

Click Like below to follow on Facebook…

When Truman Touches the Wall

15 min

The climactic scene in The Truman Show is so intensely satisfying that it still stuns me after all these years. One musical technique plays a big part in that.

Non-harmonic tones are notes that are not part of the chord of the moment but still make sense because they follow certain patterns. The non-harmonic tone that makes the climax of The Truman Show so devastatingly perfect is a pedal point (or simply ‘pedal’).

The rule for a pedal is simple: A note starts out as part of a chord, then it doggedly hangs on, even as the chords change around it. You’re still hearing that same note, maybe held out long, maybe pulsing in quarters or eighths. Sometimes it’ll belong to the chord and sometimes not, but regardless, it keeps sounding. That’s a pedal.

Tom Petty uses a double pedal all the way through Free Fallin’. Two notes are unchanging in the guitar, C and F, ringing straight through the song even as the chords change around them (39 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lWJXDG2i0A” parameters=”start=3 end=42″ /]

Sometimes it’s just a nice effect. But a pedal point can also serve the emotional purpose of establishing reality, for better or worse — a steady insistence that we accept the situation.

One of the most stunning uses of a pedal point was in the recessional at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, a piece called “Song for Athene” by John Tavener. Listen to the low F in the basses (same note as Free Fallin’). It starts right at the beginning. Better still, hum along with that long note in any octave so you can feel the music moving around that unchanging core, moving between minor and major, dissonance and consonance, darkness and light. Go all the way to 5:44 if you can — it’s one of the most profound musical settings you’ll ever hear, especially if you hum that pedal all the way:

There was a feeling of unreality when the news of Diana’s death first broke. It seemed somehow impossible. Tavener’s pedal had the effect of cementing our acceptance: Oh my God, she really is dead.

Now listen to the end of The Truman Show. The pedal begins at 1:00, those steady quarter notes down in the low strings, but don’t skip that first minute to set it up:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gn5kuDdeGzs” /]

We spent the film watching Truman struggle with uncertainty and confusion, wanting answers. When his hand touches the wall, he finally has his answer — and the pedal, the music of finality, tells us it’s true.

Follow Dale on Facebook…

That Time Stravinsky Aimed a 7th Chord at America!

A n article that crossed my Facebook last week tapped the most powerful human emotions — threatened national pride, the fear of the tall and balding, and that ancient, visceral distrust of 7th chords.

While guest conducting the Boston Symphony in 1944, the composer Igor Stravinsky programmed his own arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as a tribute to his newly-adopted home.

It didn’t go well:

As you might expect, Stravinsky’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” wasn’t entirely conventional, seeing that it added a dominant seventh chord to the arrangement. And the Boston police, not exactly an organization with avant-garde sensibilities, issued Stravinsky a warning, claiming there was a law against tampering with the national anthem. Grudgingly, Stravinsky pulled it from the bill.

Make sure you’re on a secure server before you listen to Stravinsky’s illegal arrangement (1:54):

(Those are dominant 7th chords at 0:21, 0:42, 1:15, and 1:30.)

The arrangement is incredibly tame, especially for Stravinsky, and light-years from anything that can be called “avant-garde.” Oh sure, he threw in some interesting non-harmonic tones. But the fact that it’s only in one key at a time makes it one of the most conventional things Stravinsky ever wrote. Whether it was wildly unconventional for 1944 (nope) or for the Boston Symphony in 1944 (nope) or for a setting of the National Anthem (barely) is not that interesting to me. It was unusual enough to get the attention of the Boston PD, which is funny and apparently did happen. Stravinsky was fined $100 under a misapplied interpretation of a dumb but actual Massachusetts statute.

As weird as all that is, one detail of the article got my attention:

Stravinsky’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” wasn’t entirely conventional, seeing that it added a dominant seventh chord to the arrangement.

Oh fer…okay. Where to start.

Music is a mystery to most people, I get that. But there’s a common tendency to not even try, and to assume that the not-trying won’t be noticed. A film that painstakingly researches whether a particular style of eyeglasses was available in 1924 before putting them on the face of an extra in the distant background will nonetheless focus on a clarinetist tootling away in a jazz band with his hands reversed on the instrument — even though the set of all former middle school clarinetists must surely outnumber the set of all eyeglass-period-style-knowers. And when an otherwise brilliant montage in the movie Stardust has Tristan playing an audible major triad while the actor presses three random keys — something inside me dies.

Yes I know, starving children and all.

The story of Stravinsky’s felonious dominant seventh is even weirder than a careless error, like not knowing the clarinetist’s left hand is on top. Instead, it’s of the “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” type. The arrangement does include a dominant 7th — several, in fact. But you’d be hard-pressed to find an arrangement of our national anthem that doesn’t include a dominant 7th. Or 95% of anything written since 1690. It’s one of the most common chords in Western music.

Here are the Beatles outlining a dominant 7th from the bottom up (8 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-VAxGJdJeQ” parameters=”start=86 end=94″ /]

It is as conventional a chord as you can imagine.

That’s not to say it isn’t a great and useful chord. Remember when I used the Batman (movie) theme to show how unstable pitches yearn to resolve by the shortest distance they can, like a half step? Good times.

And remember the one about tritones being deliciously unstable? They are.

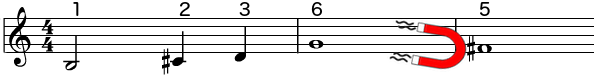

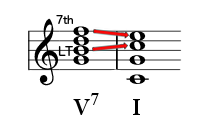

Well check this out: When you add the 7th to a regular triad — the top note in the first chord below — you get a note that’s unstable, yearning to drop a half step to a stable note in the tonic chord that follows. The leading tone (Dorothy’s “Why oh why caaaan’t…”) is already yearning to go up a half step to the tonic pitch. And, AND, those two notes together (B and F in this case) form the awesomely unstable tritone, the ‘devil in music’!

If the plain old dominant triad (V) works like a magnet to the tonic home, then the dominant seventh chord (V7) is an electromagnet. To the already neon arrow of the dominant triad, it adds the downward pull of the 7th AND the instability of the tritone. First I’ll outline the seventh chord (or the left), then play V7 moving to I:

Scandalized? More likely you’re surprised by how unsurprising it sounds. That’s the point. For all that useful instability, the V7 is about as typical and boring a musical thing as you can get.

And you know who specialized in not using ultra-conventional things like V7 chords?

Stravinsky.

So to say Stravinsky’s use of a V7 was somehow “avant garde” is like saying Picasso freaked out artistic sensibilities by painting one nose per face. It is the opposite of the way he challenged norms.

The use of a fancy-pants term is also part of this game, so a better comparison is finding out there’s ‘dihydrogen monoxide’ in your swimming pool, or that a poet was caught using an ‘interrogative’. It’s like saying Guy Fieri shook up the cooking world by using ‘sodium chloride’ on eggs. The only way your surprise needle moves is if the fancy term (in this case, ‘dominant 7th’) is new to you.

So whether or not Stravinsky was guilty of assaulting our national anthem, the dominant 7th chord wasn’t involved in the crime. Of course its fingerprints were on the anthem. That’s because it lives there. And everywhere else.

How One Note Turned David Cameron to the Dark Side

- July 31, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

Walking from the lectern after announcing his intention to resign as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Cameron did something funny: he sang a happy little tune to himself.

Well, he thought he sang it to himself. His mic was still live, so he actually sang it to the whole world:

I don’t know what he meant to sing, if anything — but this is roughly what came out:

Some thought they heard a bit of the West Wing theme in that ditty, while others heard the first notes of the overture to Tannhäuser. Both were wrong in a way I’ve mentioned before. Like the alien House of Cards cue, Cameron is actually singing a bunch of 4ths — Up a 4th, down a 4th, down another 4th. The ear has a little trouble sorting that out, so we fudge the unconventional notes to form a triad instead. It’s like an aural version of pareidolia, the human tendency to see patterns that aren’t really there. The “face on Mars” is a famous example.

Cameron’s ditty is actually closer to a motif that fans of the original Star Trek will instantly recognize. It’s even in the same key (2 sec):

Push those notes through horns and the effect is heroic. But when those same notes fall from the doughy face of a Prime Minister who just washed his hands of the biggest mess in recent British political history — especially when said notes are wearing the goofy non-lexical vocables doot-doo — it can only mean one thing: I’m a happy little fella.

Chris Hollis, a guitarist in a British pop punk band, had a darker plan for those notes: turn Happy Little Fella into Evil Tory.

That’s hilariously awesome. But how did he turn something so happy so damn dark? The low brass, cellos, and percussion helped, but that’s not enough. If those instruments had played the exact stack-o’-4ths that Cameron sang, it wouldn’t have sounded evil:

So aided by Cameron’s tunelessness, Chris cheated, just a bit, auto-tuning the last note down a half step. As D turns to Db, Gomer Pyle turns to Darth Vader:

That tiny change has a huge effect because of one of the most counterintuitive things in music: pitches that are close to each other on the keyboard (like C and Db) are miles away from each other harmonically, and therefore emotionally.

The tonal center of Cameron’s little tune is C. By fudging the last pitch down from D to D-flat, Hollis creates a strong dissonance with C and turns a 4th (G-D) into a tritone (G-Db), one of the most dissonant intervals. He then harmonizes the whole thing as C minor – Db minor, two chords that are about as far apart harmonically and emotionally as you can get. (More on this when we get to the circle of fifths.)

In a way, Hollis did the opposite of pareidolia: he took something slightly face-like, and instead of nudging it into a face, he made it more like the yawning mouth of hell. The sudden switch from goofy to evil is comedy gold.

Yes, ‘Stairway’ Was Stolen…Just Like Everything Else

- June 26, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

A jury decided that Led Zeppelin did not steal the iconic opening measures of “Stairway to Heaven” from a passage in the song “Taurus” by the band Spirit. Some people think Zeppelin got away with murder, arguing, “Well just listen to it, jeez!”

In fact, they got away with composing.

Whole-cloth ripoffs like “U Can’t Touch This” aside, the idea that it’s wrong to use a string of notes someone else once used in a similar way stems from a modern misunderstanding of how music is created — the unhelpful romantic myth that every new piece of music is a unique snowflake crafted from the purrs of unborn kittens in the soul of the composer.

In fact, nearly every piece of music you love is made up of 99.9 to 100% recycled materials. That’s not an accident: Composers return again and again to the shapes and patterns in our established musical lexicon because that’s what composing is.

Yes, there are exceptions — mostly radically avant garde pieces that try to make a virtue out of keeping you perpetually balanced on the back legs of your chair. That approach leaves a pretty narrow range of emotional states to explore, things like anxiety and puppy-slapping irritation. Once you’ve rejected all shared musical language, you can mostly forget slowly unfolding emotional experience.

To see what I mean, and why the Stairway lawsuit (and Blurred Lines, and Creep, and yes, even My Sweet Lord) was dumb, let’s take a peek into the workshop.

A Big, Finite List

Most Western music derives from a finite number of raw materials. It’s a big number, but still finite. You have 12 pitches arranged into two main scale types (major and minor), with occasional side trips into five others.

Western harmony is based on triads — three notes stacked in thirds. There are four kinds: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. You can also keep stacking thirds, adding a 7th, a 9th, or an 11th to the triad, and so on.

When a pitch sounds that isn’t in the chord of the moment, it’s a nonharmonic tone, of which there are about 12 types — passing, neighbor, suspension, anticipation, and so on.

Pitches arrange themselves over time in meter and rhythm. Each beat can be divided up into smaller bits, usually in 2, 3, or 4 parts, sometimes something stranger like 5. The most common meters are recurring bundles of 2, 3, or 4 beats called measures, sometimes 6, less often 5, 7, 9, or even 33 beats per measure.

Measures are usually in groups of 4 called phrases. Though it’s rare to have a piece based entirely on three- or five-bar phrase lengths, one of the best emotional devices in music is an occasional abbreviated or extended phrase. Nicely messes with your expectations.

The tonic chord usually goes to V or IV, sometimes to iii or vi, less often ii or vii. Mixing the usual with the unusual is the crux of the game.

Different genres of music have certain core instrumentations. A rock band usually has a guitar or two, bass, drums, and vocals. Sometimes a keyboard. Sometimes horns. Sometimes a flute or banjo. Orchestra has ABC, funk band has DEF, polka band has XYZ. So within a certain genre, the choices are even more constrained, and the similarities between pieces multiply.

On it goes, a large but finite set of variables in pitch, meter, rhythm, instruments. The amazing thing is that such an incredible variety of genres and songs has come out of this large but finite set.

Within the choices available are patterns and combinations that produce certain emotional effects — tension, calm, dread, humor, gravity, power, violence, aspiration, momentum, flight. The existing set of musical elements is drawn on over and over by composers to produce these effects in the same way a million writers dip their buckets into the shared well of language, drawing out existing words and phrases and allusions to produce the effects they need.

When writers need to evoke “bittersweet yearning,” they don’t start cobbling together letters into new combinations to see what might feel both bittersweet and yearny. They draw on the large but finite set of words and phrases that have already been used to capture that feeling.

Music works the same way. You want bittersweet yearning? Try a I-iii progression. It’s been done a thousand times, but that doesn’t mean I can’t do it again, a little differently, and create something that is new but (here’s the point) not unique.

The idea that each piece of music arrives fresh from the sea foam like Aphrodite on the clamshell, and that it must evoke no other existing song, is both detached from reality and paralyzing to the songwriter. When I studied composition, I can’t tell you how many times I sat down at the piano to come up with the germ of an idea, plunked out three notes, and said, Nope…Stravinsky. Three more notes: Nope…Bartok. Frustrated silence: Nope…Cage.

It’s a weird modern conceit. Bach did not tinkle out a phrase and mutter, Nee… Buxtehude. Nee…Couperin. Sheiße! Nor did he write music that had already been written. He used and adapted patterns and combinations that almost always had been used before. You use them in new ways, extend them, evolve them — but you don’t set out to utterly avoid every resemblance to what already exists. The whole idea is bizarre. It seems like it’s encouraging originality, but it’s actually deeply anti-creative.

The Case of Stairway v. Taurus

Stairway to Heaven is exactly as “stolen” as everything else you’ve ever heard. When he sat down to write the song, Page drew on existing materials and norms to create something new. Randy California did the same when he wrote Taurus. In the process, they crossed into similar territory for a few bars.

Both started with the commonest clay: 4/4 meter, the key of A minor, and an acoustic guitar outlining the chords in straight eighth notes and four-measure phrases — each choice so common as to be essentially the default.

Then they both chose a device that’s rich and evocative, and not original to either of them: a descending chromatic bass line (going down by half steps). It’s a device so well established that it has a name — the “lament bass” — and variations of it pop up in everything from Bach’s “Crucifixus” to the Beatles’s “Michelle” to “Chim Chim Cher-ee.” Follow that bass line (13 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG6O4N3wxf8″ parameters=”start=7 end=20″ /]

So the descending chromatic bass isn’t default, but it’s a well known device. The question as always is what you do with it. The composer of “Taurus” did this (28 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xd8AVbwB_6E” parameters=”start=44 end=72″ /]

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

Here’s what Page did with the same bass line (27 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9ioyEvdggk” parameters=”end=26″ /]

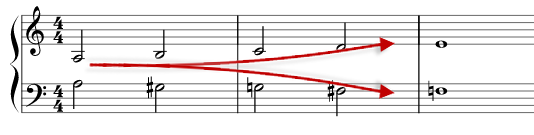

That’s greatness. In addition to the descending bass, Page laid an ascending scale into the upper line (circled notes). Sometimes a pitch is displaced by an octave or off the beat, but your ear hears the ascending line. This creates a wedge that slowly opens — unison, third, fourth, sixth, and finally that delicious major seventh — before returning to the unison/octave:

I’ve pulled out the lines so you can hear them better:

The result is a nuanced, haunting passage written by an artist who knew what he was doing. And this doesn’t even crack open the inspired work in the next hundred measures. I might come back to that.

So: was Stairway directly inspired by Taurus? Who knows. In a better world, Page could stand up and say, “That’s right, I got the idea straight from Taurus. Then I made it better. That’s how this bloody thing works.” And composers would stop suing other composers for composing.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Full songs: Spirit, Taurus; Led Zeppelin, Stairway to Heaven

Jimmy Page image by Dina Regine via Flickr | CC 2.0

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

I’m Not Saying Aliens Wrote This House of Cards Cue…

House of Cards is brilliantly scored, soup to nuts. Last month I wrote about the opening title theme. But one cue is even more special — the evocative underscoring that often makes an appearance when Frank and Claire share a cigarette and conspire. It’s called “I Know What I Have To Do”:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/fo781LEHbqc” /]

Apparently it’s special to other people as well: several videos on YouTube will teach you how to play it — an unusual tribute for a background cue. As a bonus, most of them will teach you how to play it wrong (16 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fmchtLg743I” parameters=”end=16″ /]

Nope. Try again (10 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpbAirHi3K0″ parameters=”start=70 end=80″ /]

Sorry, no.

I’m not pointing out these errors to be a pedantic little theorywanker. That’s just a bonus. The understandable errors they’re making reveal something cool and interesting about the piece itself: the fact that it was written by aliens.

You know when kids are first learning to speak, and they say things like, “I goed to the farm and seed the sheeps”? It’s called overregularizing, and it’s actually a sign of sophistication in the learner. Instead of making the daft and pointless transformations from go to went, see to saw, and sheep to sheep, kids regularize all the verbs and plurals to the perfectly good rules they’ve learned, and Bob’s your uncle.

The same thing is going on musically in the errors that pop up when Earthlings try to figure out this House of Cards cue.

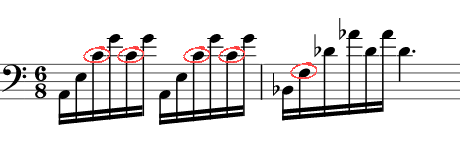

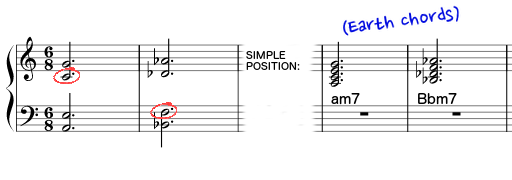

In the harmony post, I mentioned that most Western music is based on piles of thirds. Our harmonic language is triads with notes a third apart:

Our ears are used to that map. Give us harmonies based on thirds and our compass points home. The wrong tutorials are “fixing” what they hear to give the illusion of knowing which way is north.

Here’s what the tutorials above are doing (wrong notes circled):

Simplified into chords:

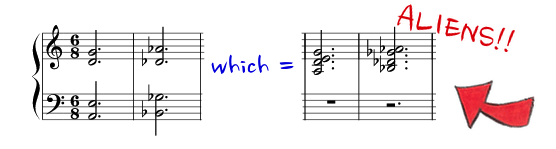

But this House of Cards cue isn’t based on thirds (tertian). It’s quartal and quintal — built with fourths and fifths.

Fourths and fifths are great and common in melodies. The first two notes of Amazing Grace are a fourth, as are the first two of Taps. The first leap in Star Wars is a fifth. They also appear all the time in harmony. But when they do, they are mostly flippable into simple position triads — a pile of thirds, as seen in the perfectly Earthly chords above.

But not this time. This music is unflippably strange:

The notes are now right, which is to say they’re correctly wrong. Musicians, look at that bloody mess. What key has Gb, G, Ab, A, D, Db, and E natural? Then there’s that fourthi-fifthiness. Here it is, simplified:

Look at that! Notes all sticking out to the sides, making Baby Jesus cry. It’s just wrong, even without the right hand melody, which makes it even stranger when added in. But that wrongness is why it’s worth talking about. Compare them side by side now, Earthling first, then alien:

It’s subtle, but believe me, the hairs on your neck know the difference.

Like little kids “fixing” grammar, the tutorials are accidentally adjusting the strangeness into something that makes sense. By budging two notes, they turn fourths into thirds, went into goed, alien music into something we can understand. In so doing, they erase a lot of the eerie quality — that unmoored, homeless fourthiness.

Now sure, you can have fourths and seconds and sevenths and all sorts of other things in normal Western Earth music. But there are rules for how they move to harmonically stable intervals, dammit, and these just aren’t following those rules. They’re sliding from one unstable, unholy mess into another.

By the way, I’ll tell you what compositional technique he used to arrive at this. It’s one I used all the time when I was trying to get outside of the box. It’s called Flopping Your Hands on the Keys to See if the Seed of Something Cool Comes Out. I say this with 99% confidence.

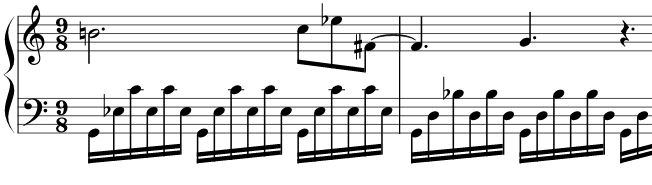

Not true for the next few bars, which suddenly go all rulesy — but it’s the complex harmonic rules of the Romantic period:

Here’s what that sounds like (12 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/fo781LEHbqc” parameters=”start=62 end=74″ /]

Oh my gourd, that is gorgeous. It could have been lifted straight from a Chopin nocturne.

Finally, here’s “I Know What I Have to Do” in scene. Turn it way up:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/0Rqm6dFvDAA” /]

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!