Owning Einstein

One of the great games in the culture wars is claiming the good and smart for your team and pushing the monsters away. Picture Christian and atheist captains in a sandlot choosing basketball teams.

ATHEIST: Einstein, we get Einstein!

CHRISTIAN: No way, he used the word God!

ATHEIST: Well Jefferson then.

CHRISTIAN: You WISH!

And so it goes until only Hitler is left, standing alone in short pants.

The push-me-pull-you process is done by cherry-picking quotes, and Albert Einstein is the three-point shooter everybody wants. To complicate that, I’m including five excerpts from Einstein’s correspondence, adding up to a clear and nuanced picture by the end. We’ll start by picking the atheists’ favorite cherry, then keep moving around the tree.

Five excerpts from correspondence and interviews of Albert Einstein

It was, of course, a lie what you read about my religious convictions, a lie which is being systematically repeated. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly. If something is in me which can be called religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it.

Letter of March 24, 1954 to a correspondent asking him to clarify his religious views [source]

I have repeatedly said that in my opinion the idea of a personal God is a childlike one. You may call me an agnostic, but I do not share the crusading spirit of the professional atheist whose fervor is mostly due to a painful act of liberation from the fetters of religious indoctrination received in youth. I prefer an attitude of humility corresponding to the weakness of our intellectual understanding of nature and of our own being.

Letter to Guy H. Raner Jr., September 28, 1949 [source]

My position concerning God is that of an agnostic. I am convinced that a vivid consciousness of the primary importance of moral principles for the betterment and ennoblement of life does not need the idea of a law-giver, especially a law-giver who works on the basis of reward and punishment.

Letter to M. Berkowitz, Oct. 25, 1950. Einstein Archives 59–215.00

I’m absolutely not an atheist. I don’t think I can call myself a pantheist. The problem involved is too vast for our limited minds. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn’t know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God. We see the universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws but only dimly understand these laws. Our limited minds grasp the mysterious force that moves the constellations. I am fascinated by Spinoza’s pantheism, but admire even more his contribution to modern thought because he is the first philosopher to deal with the soul and body as one, and not two separate things.

From a 1930 interview with poet, writer, and later Nazi propagandist G.S. Viereck. [source]

The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honorable but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish. No interpretation no matter how subtle can (for me) change this. These subtilized interpretations are highly manifold according to their nature and have almost nothing to do with the original text. For me the Jewish religion, like all other religions, is an incarnation of the most childish superstitions. And the Jewish people to whom I gladly belong and with whose mentality I have a deep affinity have no different quality for me than all other people. As far as my experience goes, they are also no better than other human groups, although they are protected from the worst cancers by a lack of power. Otherwise I cannot see anything ‘chosen’ about them.

In general I find it painful that you claim a privileged position and try to defend it by two walls of pride, an external one as a man and an internal one as a Jew. As a man you claim, so to speak, a dispensation from causality otherwise accepted, as a Jew the privilege of monotheism…With such walls we can only attain a certain self-deception, but our moral efforts are not furthered by them. On the contrary.

With friendly thanks and best wishes

Yours, A. EinsteinLetter from Einstein to author Eric Gutkind, Jan. 1954, in response to receiving Gutkind’s book “Choose Life: The Biblical Call to Revolt.” [source]

It’s curious to see people like Einstein (and Sagan and Tyson), whose views are apparently identical to mine, framing atheism as something it almost never is –a position of absolute certainty — and rejecting the label on those terms. If theism can include strong conviction rather than certainty, atheism should as well. It’s an opinion strongly held for good reasons, not an immutable dogmatic claim.

At least Einstein makes his reasoning clear in these letters. You know, I’ll bet that puts an end to all of the confusion.

When Being ‘Out and Normal’ Mortifies the Kids

“Why did you do that?? Seriously Dad.”

It was late summer 2011, and we were driving back to Atlanta from the North Carolina reunion of Becca’s mostly Southern Baptist extended family. Even though we differ about as much as can be imagined in politics and religion, it’s a family I’m grateful for. It’s a real pleasure to watch each other raise families and get older.

As we drove, Becca and I did our usual post-game show in the front seat, with the kids chiming in from the back. At one point we hit on something that happened at dinner on the last night.

That’s when I learned that I had embarrassed my fifteen-year-old son.

“It was so awkward,” he said.

Ah. I really should have seen that coming. “I guess so. But I don’t mind a little awkwardness. Helps break the ice sometimes.”

“But this didn’t break ice!” he said, exasperated. “It MADE ice!”

Though it’s almost never mentioned, my worldview seems to be common knowledge in the family. I don’t push too many points, but neither do I leave the lowest-hanging fruit completely unplucked. Most of all, I follow the advice I give in workshops: be out and normal. Act as if there’s nothing unusual about the religious and nonreligious sharing a world, a country, a family, a table, a marriage, a friendship. There isn’t, of course. What’s unusual is for religious people to know they are sharing all these things with nonbelievers, all the time. It’s a good opportunity to see that the world spins on.

Whenever I have to figure out whether and what to say or do this or that as an atheist among the religious, I tend to operate from that one principle: be out and normal. Things usually go just fine. Once in a while, though, I end up embarrassing the progeny.

After that last supper (stop it), the family patriarch, a good-humored Baptist minister in his 70s, gave away some prizes he’d brought with him — T-shirts, pins, that sort of thing. He asked everyone to write down a number between 1 and 100. We all did.

“Now,” he said, “what I didn’t tell you is that each of the numbers I’ll read off has something to do with me.” He smiled. “The first number is…73. That’s my age.” Woohoo, someone hollered, and won a T-shirt.

Next he called the first two digits in his address, then his phone number, then his Social Security Number, giving away prizes to the closest number for each.

Then came the finale. With a bit of ceremony, he produced a small wooden box. He told a story of being approached by a man who was raising money for local church kids to go to camp, something like that. He’s a good storyteller and loves an audience, so when at length he opened the hinged box and revealed the contents, he got himself a nice Ooooooo from the congregation.

It was an unusual pendant, a chain of copper-colored beads, and hanging at the end, a large black cross with splayed ends, a kind of extended Coptic cross. It was made of black glass, maybe obsidian, with swirls of metallic blue and copper.

“Now,” he said. “I want you to write down another number between 1 and 100 to see who gets this cross.”

I could claim that I hesitated a moment, that I pondered what to do, whether to participate, but no. Instead, I did what the other 45 people in the room did — I wrote a number on the back of a piece of paper and folded it up. That was the normal thing to do. But this is the moment that was shortly to embarrass my fine boy.

When at last Uncle Bill raised his fingers to indicate the number he had chosen, I hoped that the family atheist was not the only one in the room who figured that a Baptist minister giving away a cross would choose the number 3.

But I was.

As I unfolded the paper and slowly raised it for all to see, a small gasp went up in the room, or in my head, I’m not sure which. Pastor Bill’s face went ashen, and he looked down, then up again, and sighed, then smiled resignedly. “Okay. It’s yours.”

Here’s where “be out and normal” breaks down a bit. It’s hard to quickly figure out the “normal” way for an atheist among Baptists to accept a cross that he has won by way of religious insight from a minister who is also his wife’s uncle. But it’s not hard to figure out why the same moment embarrasses the atheist’s teenage son, sitting at a table with his Baptist cousins.

That I get.

Still, I can’t picture myself doing it differently — like not writing a number down, or taking Connor’s later advice — “You could have just not shown it!”

But I did show it. And I accepted the cross respectfully, praised the craftsmanship — it really is a striking piece — and later restored color to the pastor’s face by telling him I would give it to his devout sister in recognition of her 20 years as my mother-in-law.

Worth an awkward moment, I think — even if my boy would disagree.

The Eclipse of Darwinism

As an anthro major, I learned that Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection underwent a barrage of criticism after the Origin was published and before the modern synthesis with genetics clinched the deal.

But I didn’t know until years later just how bad it got.

In his 1942 book about the modern synthesis, Julian Huxley described the 1880s to 1920s as “the eclipse of Darwinism.” Support for the theory actually dwindled during that period, with ever more biologists feeling it was inadequate to explain all the evidence. Probably didn’t help that Darwin kept putting out ever-weaker new editions as he bent over backwards to answer concerns without access to the evidence that would eventually put the theory over the bar. For a while, it was plausible that Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection would be completely thrown over as alternatives were explored, including

• Orthogenesis (the idea that life has a natural tendency to change over time in a single direction without external cause)

• Neo-Lamarckism (that the features acquired by parents during a lifetime are passed on to progeny)

• Mutationism (that new species are created in a single step by mutation)

• Theistic evolution (that a supreme being causes the gradual change of forms according to a divine plan)

What Darwin’s theory had lacked was a recognized mechanism for heredity. That mechanism had been figured out by Gregor Mendel and even published in the Proceedings of the Society of Nine Isolated Moravians in 1866. But it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that biologist William Bateson and the statistician Udny Yule connected Mendel and Darwin, setting in motion the modern synthesis that would eventually snap everything into place. By the time Huxley’s book named the synthesis in 1942, no substantial dissent remained among biologists. Darwin’s theory was the accepted explanation for the diversity of life on Earth.

It’s an even better example than I thought of how science works.

Podcast Ep 1: The Evolution of Cool

It begins! my new podcast HOW MUSIC DOES THAT is now live. Episode 1 explores the surprising link between evolution and the element of cool in music.

When Someone Asks How You Raise Moral Kids Without the Bible, Here’s the A+ Answer

A few years ago I was interviewed briefly on NPR’s On Point about moral development without religion. I managed to get my major point made — that moral development research shows that the process is aided more by a questioning approach than by passive acceptance of rules. But I gave a B- response to his next question, which was basically, “Without the Bible, what books do you use to guide moral development?”

I’m still kicking myself for my answer. Like a second-rate interviewee, I accepted the premise of his question: that moral development has something to do with books or other static sources of insight. I jibbered something about a wide range of sources being available, from Aesop’s Fables to even religious texts read humanistically — The Jefferson Bible and all that.

The A+ answer is that it isn’t a book thing at all. Moral development research — Grusec, Nucci, Baumrind, the works — has shown that moral understanding comes first and foremost from peer interaction. That’s why kids start framing everything in terms of fairness around age five, right when most of them are starting to have regular, daily peer interactions — including the experience of being treated fairly and unfairly, and making choices about how they will treat others, and feeling the consequences of those choices.

There’s also a slice of humble pie for parents in that research. As much as we would like to think we’re inculcating morality into our kids, that’s mostly rubbish. Sorry. We have a role, we’re just not as central as we’d like to think. We can and should help kids process their experiences and articulate their thoughts about them, but it’s the experience itself that provides the main text from which they draw moral understanding — not us, and not a book.

So there’s my rewrite. Extra credit, at least?

I Heart Harmful Books

As I was writing the section on “Lost, Secret, Censored, and Forbidden” books for Atheism for Dummies, I came across a list on the website Human Events — Powerful Conservative Voices naming the Ten Most Harmful Books of the 19th and 20th Centuries.

Oh, ka-LICK!

It was not just the nonsensical ravings of some random guy. That’s fun too, but too easy and cheap — there’s always that guy somewhere. This list gathered the opinions of “15 conservative scholars and public policy leaders.” Human Events has been around since WWII (initially in print form) and was Ronald Reagan’s “favorite reading for years.”

The result was even better than I’d hoped. In addition to questioning the whole concept of the harmful book, I thought some on the list were just too funny. The Kinsey Report? The Feminine Mystique? Dewey’s Democracy and Education? (The listmaker moans that Dewey introduced the teaching of thinking “skills” — scare quotes included — into public education. Bastard!)

Even better are some of the runners up: Mill’s On Liberty; Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed (which harmfully made cars less dangerous); Origin of Species and Descent of Man (of course); Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex…and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring!

Lists of banned books are so damn revealing. In this case, nearly every book on the list, including the runners-up, is challenging the status quo, holding prevailing assumption to the light.

Stephen King’s advice to a group of students was spot-on:

When you hear a book is being banned, RUN, don’t walk, to the first library you can find and read what they’re trying to keep out of your eyes. Read what they’re trying to keep out of your brains. Because that’s exactly what you need to know.”

Slow Your Roll (Reich, Electric Counterpoint)

(#14 on Laney’s List)

Minimalism is not for everyone. But before you decide, you have to try meeting it on its own terms. It’s aiming at a different kind of musical experience, one that’s less linear, more about sitting in the moment.

Instead of the musical structure we’re used to — straight lines moving forward in measured time — minimalism tends to establish an atmosphere or pattern, let it dance a while, then slowly evolve. If you let yourself sit in each pattern without waiting impatiently for Next and Next, there’s a whole different kind of pleasure there. And when the change does come, it can be exquisite. You experience both the stasis and the change in a new way.

I gave you some zero-entry Reich with the short clip from Sextet. This is a bigger bite, but also (I think) a bigger reward. Three continuous movements, 15 minutes of solo electric guitar with recorded overdubs. I love the stasis, but I mmmmLOVE the transitions, so I’ve given those timings below.

I. Fast (0:12-7:02)

Three sections of nearly identical length (~2:20). Listen for the transitions at 2:20 and 4:40.

II. Slow (7:02-10:24)

Two slow and lovely sections of ~1:40 each, transition at 8:45.

III. Fast (10:24-15:00)

This one is more of a single continuously developing idea. I adore it, especially from 11:06 on. The guitarist Mats Bergström clearly agrees — check out the slightly NSFW moves at 12:48.

14. REICH Electric Counterpoint (15:00)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MOAS6ik796s” parameters=”start=10″ /]

ALSO GREAT: Johnny Greenwood performs Electric Counterpoint live

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | 13 Mozart | 14 Reich | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale on Facebook:

Hiding in Plain Sight: The Greatest Musical Easter Egg Ever

5 min

I just tripped over a music theory Easter egg that’s been hiding in plain sight for 50 years. It’s easy to understand with a little explanation, and it just had to be intentional.

Last week I wrote about Mozart’s use of non-harmonic tones — pitches that don’t belong to the chord of the moment:

They usually fit one of 12 rules (patterns with the notes around them), which is how your ear makes sense of the pitch despite it being a chordal immigrant.

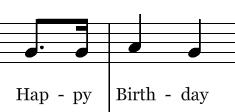

One of the simplest non-harmonic patterns is the neighbor tone. Start on a note that’s in the chord, go up or down a step, then back to the first. That’s a neighbor tone. The syllable birth in the crime against humanity called “Happy Birthday” is an upper neighbor. See? It’s right next door.

Go down instead of up and you have a lower neighbor, a lа̀ Jurassic Park:

0:07

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=msimASAXoys” parameters=”start=171 end=178″ /]

Here’s the Jurassic melody with the neighbors marked:

And when Whitney Houston sang And ahhhhh-eee-yaaaii will always love yooou, the “eee” was an upper neighbor.

You get the idea.

I wanted one more neighbor tone for this post, so I started singing the lower neighbor pattern to myself, like the three Jurassic notes, to see if anything popped into my head. Dah-dah-dah, I sang.

Dah-dah-dah, dah-dah-dah, I sang, then a little faster. DAH-dah-dah DAH-dah-dah.

Wait.

Oh my god, no way.

And also OF COURSE.

The theme to Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood…is absolutely brimming with neighbors.

You think this is a coincidence, I can tell. Let’s just see about that.

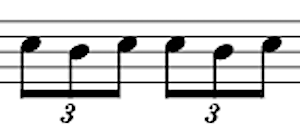

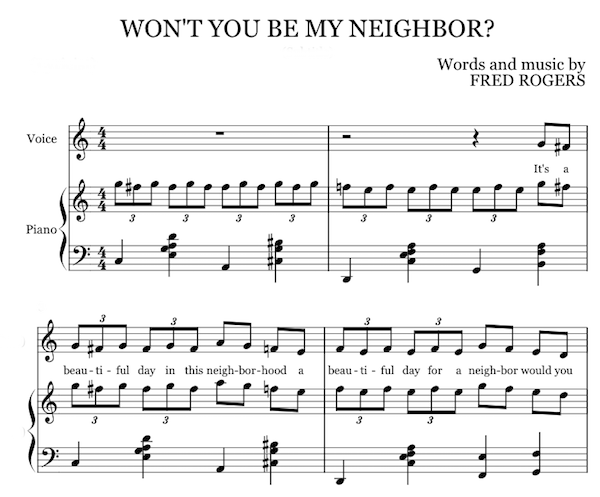

Fred Rogers wrote the words and lyrics himself in 1967. He changed it a bit for the show — more on that below — but fortunately his original arrangement is still in publication, so we can see his intent. I’ve transposed the first four bars to the key he sang in the show:

It’s not surprising that he wrote his own theme song — Rogers’ 1951 bachelor’s degree was in music composition. And when somebody with a degree in music composition writes a song with the word “neighbor” in it 6,000 times and includes neighbor tones in the melody, that’s no coincidence. It’s easy to imagine his quiet satisfaction at a geeky inside joke that virtually no one would ever get.

Hm. You’re still unconvinced. So this fairly common non-harmonic note pops up a couple of times in the song, you say, big deal. That doesn’t mean it was intentional.

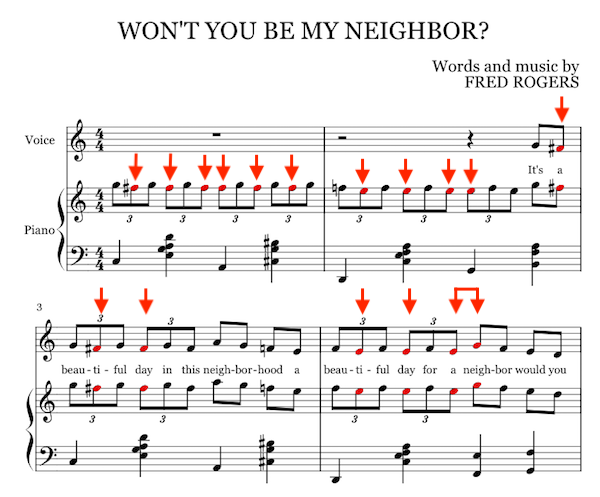

Here are those four bars again with the neighbor tones marked:

Seventeen neighbors in four bars, including a double neighbor on the word neighbor? This is too densely-populated a neighborhood to be a coincidence. This is a music major having fun.

Interestingly, by the time the show premiered in 1968, he ironed most of the neighbors out of the vocal line, substituting a straight line of Gs. Maybe he felt the waggling back and forth got in the way of understanding the words, or that it would be too hard for the kids to sing along at home, especially the way it throws off the accent in the triplets. I can easily see him sacrificing his little inside joke so we could feel more comfortable.

But it isn’t completely gone. In addition to several remaining spots in the vocal, listen to the celeste (0:06-0:10) and the piano (0:24-0:28). Still brimming with neighbors.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eInUUfyqa5o” /]

Follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

When the Music Doesn’t Trust You

15 min

A few posts back I wrote about mickeymousing, a film scoring technique in which the music closely imitates actions on screen. Good for cartoons and parodies, bad for most everything else. Another usually no-good technique is continuous scoring, also known as wallpaper.

Wallpaper is film music that never seems to shut up. Instead of trusting the audience to know how to feel, it nudges and winks every time the emotion turns even slightly — Ooh see? It’s happy. Oh, now it’s sad. Oh! He surprised her. The genre films of Hollywood’s “Golden Age” (1927 to early 1960s) are notorious for unrelenting wallpaper of the distrustful kind.

High Noon (score by Dimitri Tiomkin) is a classic example. BONUS MOMENT: At 1:50-2:00, as Glinda the Good Witch chastises the sheriff, the movie’s main theme “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling” plays in minor. Five seconds later as she says, “Oh Will, we were married just a few minutes ago,” it switches to major. That may be the hammiest moment in all film music.

1:34

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rm0iEYCUw5I” parameters=”start=58″ /]

Here’s some typical wallpaper from the 1940s — The Strange Woman (score by Carmen Dragon):

1:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNsgtXnukyE” parameters=”start=2716 end=2801″ /]

That kind of wall-to-wall scoring mostly ended in the early 70s. But continuous scoring still makes an appearance, often with great results. When it maintains a single emotional arrow toward a climax instead of shadowing every emotional change, it can be really effective. That’s especially true when the music persists despite emotional shifts in the action, as it does in this stunning scene from There Will Be Blood (main score by Johnny Greenwood, this scene by Arvo Pärt):

2:22

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ugTbwvVuLKA” /]

Two small pauses, but still mostly continuous.

Then there’s my favorite, the kind of continuous scoring that serves as a unifying emotional thread through a montage of scene cuts. First this gorgeous, moving sequence, again from There Will Be Blood (Johnny Greenwood):

2:37

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0dlraJXats” /]

Then there’s this heartbreaking thing. Instead of distrust, the continuous scoring plays a crucial part in establishing the emotion — and it takes me to pieces every time I see this film (Love Actually, song by Joni Mitchell):

2:24

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2y-8vxObugM” parameters=”start=72″ /]

Finally there’s the kind that elevates a scene, makes it epic. Repeating and building as it goes, this scoring by Hans Zimmer imbues a few mundane actions — man deplanes, walks through customs, arrives at house, greets children — with power and significance (Inception):

3:42

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQPy88-E2zo” /]

Follow Dale on Facebook:

Mozart in Eight Sobs (Lacrimosa)

12 min

(#13 in the Laney’s List series)

When my brother and I were teenagers, we knew just enough about music to be insufferable. We’d listen to something by Mozart that we hadn’t heard before, and as the end of each phrase approached, we would sing the last measures, then laugh at how spot-on we had guessed it. Stupid, predictable Mozart.

If you want to reach across the decades and slap us, you’ll have to wait behind him and me both.

Once Charles Rosen and some education and experience had their way with me, I realized that our spooky predictive powers stemmed from the fact that Mozart had done more than almost anyone in creating those expectations.

Mozart was a composer in the Classical style from his first harpsichord minuets at age four (K. 1) to the Requiem Mass at 35 (K. 626). Instead of destroying the box of the period he was born into, he explored and defined the box, then played every possible game with it before folding it up into an exquisite origami model of Vienna. So much for boxes, said Beethoven, who ran naked into the forest of Romanticism.

We’ll chase those retreating buns later.

But some of Mozart’s compositions did look forward to the Romantic style, and the Requiem was one of those — not just in the music, but in the web of mythology that was spun around it after his death.

Most of what most people think they know about Mozart’s Requiem came from the film and play Amadeus. The actual circumstances of its composition are almost as strange as the myths.

The play and film depict a shadowy commission of the Requiem from the gravely ill Mozart by the composer Antonio Salieri in disguise, who plans to pass the composition off as his own when it is performed at Mozart’s funeral. But after Mozart dies, his wife Constanze tears the score from Salieri’s hands and locks it away. Funeral, burial, curtain – and the fate of the unfinished Requiem is left a mystery.

In reality, the Requiem was commissioned by a minor composer named Count Walsegg who wanted to pass it off as his own. It’s something Walsegg was apparently known for — he would commission a piece, then have a private concert for friends, claiming he wrote it. I imagine they humored him for the pre-concert schnitzel and schnapps.

Mozart did die before finishing the Requiem, and it’s then that the story gets interesting. Constanze solicits the help of Mozart’s friend Süssmayr and others in finishing the Requiem, then rushes it to publication and performance, carefully omitting the fact that Mozart didn’t write the whole thing.

She had good reason for the deception. Remember her line in the film, “Money just slips through his fingers, it’s ridiculous”? It was true. He’d left his family in dire financial straits, and she naturally wanted to maximize the income from his last composition. “Mass for the Dead Written by W.A. Mozart on His Deathbed” sells way more tickets than “Mass started by W.A. Mozart and Finished by Some Guys.”

But I have to think close listeners knew something was up when they heard it. The 14 movements of Mozart’s Requiem vary from breathtaking to meh. Even on the edge of the grave, Mozart would never have phoned in a tediosity like this:

0:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DpQoKW-1VbE” parameters=”start=7 end=33″ /]

That’s the Sanctus. There’s nothing wrong with it, which says it all. It’s just forgettable. And sure enough, it’s a Süssmayr.

The Sanctus is a checked box, a solid B. But the Lacrimosa movement was written by a whole different animal, namely Mozart. To see how Mozart mastered the details, I’ll focus on just the first eight beats of the Lacrimosa, and only one aspect of that brief passage.

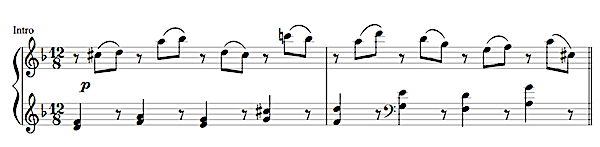

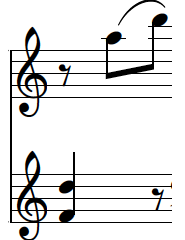

Lacrimosa (“Full of Tears”) is about the anguish of damned souls on the day of judgment. It opens with eight slow beats of three notes each — one low, answered by two high, like so:

0:12

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVRM56M61v8″ parameters=”end=12″ /]

There’s so much there to talk about, but I’ll stick to just one — the selection of pitches. If Süssmayr (or I) had written those bars using the same bass line, it might have sounded like this:

Each of those “sobs” is just…you know, fine. Nothing incorrect, every choice safe and normal. There’s little variety, partly because every note is a chord tone, meaning it belongs to the triad for that beat. As a result there’s very little dissonance, which is what tears are made of.

By contrast, Mozart’s sobs are full of yearning dissonance, and more often than not, that dissonance comes from non-harmonic tones — pitches foreign to the triad of the moment. For a D minor triad, for example, the chord tones are DFA, and if you play a G, that’s a non-harmonic tone. They usually fit one of 12 rules (patterns with the notes around them), which is how your ear makes sense of the pitch despite it being a chordal immigrant. I’ll eventually write more about these fantastic notes, but for now I want to show how the skilled use of non-harmonic tones helps to make Mozart Mozart.

I’ve isolated each of the eight sobs of the Lacrimosa below and slowed them down in brief audio clips so you can hear the non-harmonic tones (red circles).

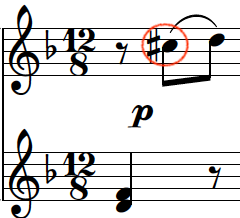

Sob 1

Hear how the C# creates a searing tension before going up to the D? That’s a non-harmonic tone. In that faux Süssmayr clip above I changed it to an A, which is part of the triad, so there’s not much tension or interest. C# is better — it’s a non-harmonic tone called a displaced neighbor, and it aches against the low D before resolving upward.

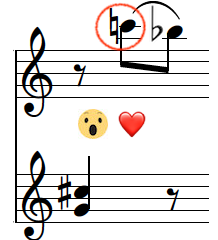

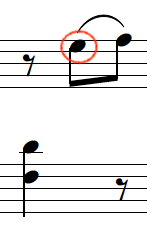

Sob 2

Sob 2 reverses the poles: the first note on the top line is in the chord and the second is the non-harmonic. This time the pattern is called an escape tone — a B♭ pops out the top, knocking boots with the As below.

Sob 3

The D is an appoggiatura, my favorite non-harmonic, one I definitely don’t have to look up every single damn time I spell it. See how the eighth notes in Sob 1 are dissonant→consonant and in Sob 2 are consonant→dissonant? Even if you call both of the eighths in #3 chord tones, they are both dissonant against the lower notes, forming a 7th and a tritone respectively (the devil in music). And notice that we’ve now had three upper notes in a row that are dissonant, which builds the tension.

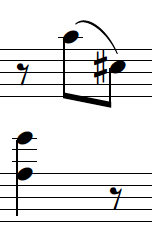

Sob 4

This is the one, oh my god, this is the beauty. Those bottom two notes form a tritone, G and C#, that’s nice. But the corker is the next one, that high C. I’ve written before about the melodic minor scale and the fact that the 7th note in the scale can be raised or lowered depending on whether the line is going up or down from there. But here you get both forms of the note at the same time — C# against C. Play that clip again. Combined with the tritone, it’s just achingly lovely, and the tension that’s been ratcheting up for the past two sobs reaches peak density.

Sob 5

Then right at the midpoint of the phrase, the tension is released: Sob 5 is all chord tones and an expressive leap up the the peak of the phrase, the high D. Now we’ll start tumbling down with the next sob.

Sob 6

This one’s a nice little crunch called a diminished triad. The E and B♭ form a tritone, the “devil in music” again. Looking ahead, you can see we’re in a tumbling pattern melodically — after climbing to that high D (Sob 5) we drop down in 6, small reach upward in 7, big fall in 8.

Sob 7

D against E is a 9th, an elegant clash. The E is a non-harmonic called a displaced passing tone. (I’ll write more about the twelve kinds of non-harmonic tones eventually — they are the spice.)

Sob 8

We’ve reached the cadence now, the harmonic punctuation at the end of a phrase, so nothing fancy here. It’s a half cadence, meaning it ends on an arrow pointing to our minor home, which is where the choir comes in. The sobs then continue under the entrance of the voices, unifying the emotion like a ground bass.

When you realize that this is a light analysis of one aspect of the first 12 seconds of one movement of one piece by Mozart, you can start to see why his music is playing in a hundred places around the world every minute of every day 250 years later, while poor Süssmayr’s Wikipedia page says, “Popular in his day, he is now known primarily as the composer who completed Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s unfinished Requiem.”

13. MOZART “Lacrimosa” from Requiem Mass (3:20)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVRM56M61v8″ /]

EXTRA CREDIT Four-pepper theorists will enjoy working out the Romans for 0:24-0:48. It is a four-bar harmonic master class.

1 Chopin | 2 Scarlatti | 3 Hildegard | 4 Bach | 5 Chopin | 6 Reich | 7 Delibes | 8 Ravel | 9 Ravel | 10 Boulanger | 11 Debussy | 12 Ginastera | 13 Mozart | Full list | YouTube playlist

Click LIKE below to follow Dale on Facebook: