That Time Stravinsky Aimed a 7th Chord at America!

A n article that crossed my Facebook last week tapped the most powerful human emotions — threatened national pride, the fear of the tall and balding, and that ancient, visceral distrust of 7th chords.

While guest conducting the Boston Symphony in 1944, the composer Igor Stravinsky programmed his own arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as a tribute to his newly-adopted home.

It didn’t go well:

As you might expect, Stravinsky’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” wasn’t entirely conventional, seeing that it added a dominant seventh chord to the arrangement. And the Boston police, not exactly an organization with avant-garde sensibilities, issued Stravinsky a warning, claiming there was a law against tampering with the national anthem. Grudgingly, Stravinsky pulled it from the bill.

Make sure you’re on a secure server before you listen to Stravinsky’s illegal arrangement (1:54):

(Those are dominant 7th chords at 0:21, 0:42, 1:15, and 1:30.)

The arrangement is incredibly tame, especially for Stravinsky, and light-years from anything that can be called “avant-garde.” Oh sure, he threw in some interesting non-harmonic tones. But the fact that it’s only in one key at a time makes it one of the most conventional things Stravinsky ever wrote. Whether it was wildly unconventional for 1944 (nope) or for the Boston Symphony in 1944 (nope) or for a setting of the National Anthem (barely) is not that interesting to me. It was unusual enough to get the attention of the Boston PD, which is funny and apparently did happen. Stravinsky was fined $100 under a misapplied interpretation of a dumb but actual Massachusetts statute.

As weird as all that is, one detail of the article got my attention:

Stravinsky’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” wasn’t entirely conventional, seeing that it added a dominant seventh chord to the arrangement.

Oh fer…okay. Where to start.

Music is a mystery to most people, I get that. But there’s a common tendency to not even try, and to assume that the not-trying won’t be noticed. A film that painstakingly researches whether a particular style of eyeglasses was available in 1924 before putting them on the face of an extra in the distant background will nonetheless focus on a clarinetist tootling away in a jazz band with his hands reversed on the instrument — even though the set of all former middle school clarinetists must surely outnumber the set of all eyeglass-period-style-knowers. And when an otherwise brilliant montage in the movie Stardust has Tristan playing an audible major triad while the actor presses three random keys — something inside me dies.

Yes I know, starving children and all.

The story of Stravinsky’s felonious dominant seventh is even weirder than a careless error, like not knowing the clarinetist’s left hand is on top. Instead, it’s of the “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” type. The arrangement does include a dominant 7th — several, in fact. But you’d be hard-pressed to find an arrangement of our national anthem that doesn’t include a dominant 7th. Or 95% of anything written since 1690. It’s one of the most common chords in Western music.

Here are the Beatles outlining a dominant 7th from the bottom up (8 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-VAxGJdJeQ” parameters=”start=86 end=94″ /]

It is as conventional a chord as you can imagine.

That’s not to say it isn’t a great and useful chord. Remember when I used the Batman (movie) theme to show how unstable pitches yearn to resolve by the shortest distance they can, like a half step? Good times.

And remember the one about tritones being deliciously unstable? They are.

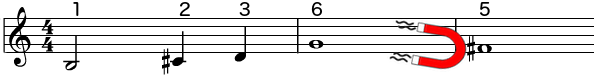

Well check this out: When you add the 7th to a regular triad — the top note in the first chord below — you get a note that’s unstable, yearning to drop a half step to a stable note in the tonic chord that follows. The leading tone (Dorothy’s “Why oh why caaaan’t…”) is already yearning to go up a half step to the tonic pitch. And, AND, those two notes together (B and F in this case) form the awesomely unstable tritone, the ‘devil in music’!

If the plain old dominant triad (V) works like a magnet to the tonic home, then the dominant seventh chord (V7) is an electromagnet. To the already neon arrow of the dominant triad, it adds the downward pull of the 7th AND the instability of the tritone. First I’ll outline the seventh chord (or the left), then play V7 moving to I:

Scandalized? More likely you’re surprised by how unsurprising it sounds. That’s the point. For all that useful instability, the V7 is about as typical and boring a musical thing as you can get.

And you know who specialized in not using ultra-conventional things like V7 chords?

Stravinsky.

So to say Stravinsky’s use of a V7 was somehow “avant garde” is like saying Picasso freaked out artistic sensibilities by painting one nose per face. It is the opposite of the way he challenged norms.

The use of a fancy-pants term is also part of this game, so a better comparison is finding out there’s ‘dihydrogen monoxide’ in your swimming pool, or that a poet was caught using an ‘interrogative’. It’s like saying Guy Fieri shook up the cooking world by using ‘sodium chloride’ on eggs. The only way your surprise needle moves is if the fancy term (in this case, ‘dominant 7th’) is new to you.

So whether or not Stravinsky was guilty of assaulting our national anthem, the dominant 7th chord wasn’t involved in the crime. Of course its fingerprints were on the anthem. That’s because it lives there. And everywhere else.

How One Note Turned David Cameron to the Dark Side

- July 31, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

Walking from the lectern after announcing his intention to resign as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Cameron did something funny: he sang a happy little tune to himself.

Well, he thought he sang it to himself. His mic was still live, so he actually sang it to the whole world:

I don’t know what he meant to sing, if anything — but this is roughly what came out:

Some thought they heard a bit of the West Wing theme in that ditty, while others heard the first notes of the overture to Tannhäuser. Both were wrong in a way I’ve mentioned before. Like the alien House of Cards cue, Cameron is actually singing a bunch of 4ths — Up a 4th, down a 4th, down another 4th. The ear has a little trouble sorting that out, so we fudge the unconventional notes to form a triad instead. It’s like an aural version of pareidolia, the human tendency to see patterns that aren’t really there. The “face on Mars” is a famous example.

Cameron’s ditty is actually closer to a motif that fans of the original Star Trek will instantly recognize. It’s even in the same key (2 sec):

Push those notes through horns and the effect is heroic. But when those same notes fall from the doughy face of a Prime Minister who just washed his hands of the biggest mess in recent British political history — especially when said notes are wearing the goofy non-lexical vocables doot-doo — it can only mean one thing: I’m a happy little fella.

Chris Hollis, a guitarist in a British pop punk band, had a darker plan for those notes: turn Happy Little Fella into Evil Tory.

That’s hilariously awesome. But how did he turn something so happy so damn dark? The low brass, cellos, and percussion helped, but that’s not enough. If those instruments had played the exact stack-o’-4ths that Cameron sang, it wouldn’t have sounded evil:

So aided by Cameron’s tunelessness, Chris cheated, just a bit, auto-tuning the last note down a half step. As D turns to Db, Gomer Pyle turns to Darth Vader:

That tiny change has a huge effect because of one of the most counterintuitive things in music: pitches that are close to each other on the keyboard (like C and Db) are miles away from each other harmonically, and therefore emotionally.

The tonal center of Cameron’s little tune is C. By fudging the last pitch down from D to D-flat, Hollis creates a strong dissonance with C and turns a 4th (G-D) into a tritone (G-Db), one of the most dissonant intervals. He then harmonizes the whole thing as C minor – Db minor, two chords that are about as far apart harmonically and emotionally as you can get. (More on this when we get to the circle of fifths.)

In a way, Hollis did the opposite of pareidolia: he took something slightly face-like, and instead of nudging it into a face, he made it more like the yawning mouth of hell. The sudden switch from goofy to evil is comedy gold.

Yes, ‘Stairway’ Was Stolen…Just Like Everything Else

- June 26, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

A jury decided that Led Zeppelin did not steal the iconic opening measures of “Stairway to Heaven” from a passage in the song “Taurus” by the band Spirit. Some people think Zeppelin got away with murder, arguing, “Well just listen to it, jeez!”

In fact, they got away with composing.

Whole-cloth ripoffs like “U Can’t Touch This” aside, the idea that it’s wrong to use a string of notes someone else once used in a similar way stems from a modern misunderstanding of how music is created — the unhelpful romantic myth that every new piece of music is a unique snowflake crafted from the purrs of unborn kittens in the soul of the composer.

In fact, nearly every piece of music you love is made up of 99.9 to 100% recycled materials. That’s not an accident: Composers return again and again to the shapes and patterns in our established musical lexicon because that’s what composing is.

Yes, there are exceptions — mostly radically avant garde pieces that try to make a virtue out of keeping you perpetually balanced on the back legs of your chair. That approach leaves a pretty narrow range of emotional states to explore, things like anxiety and puppy-slapping irritation. Once you’ve rejected all shared musical language, you can mostly forget slowly unfolding emotional experience.

To see what I mean, and why the Stairway lawsuit (and Blurred Lines, and Creep, and yes, even My Sweet Lord) was dumb, let’s take a peek into the workshop.

A Big, Finite List

Most Western music derives from a finite number of raw materials. It’s a big number, but still finite. You have 12 pitches arranged into two main scale types (major and minor), with occasional side trips into five others.

Western harmony is based on triads — three notes stacked in thirds. There are four kinds: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. You can also keep stacking thirds, adding a 7th, a 9th, or an 11th to the triad, and so on.

When a pitch sounds that isn’t in the chord of the moment, it’s a nonharmonic tone, of which there are about 12 types — passing, neighbor, suspension, anticipation, and so on.

Pitches arrange themselves over time in meter and rhythm. Each beat can be divided up into smaller bits, usually in 2, 3, or 4 parts, sometimes something stranger like 5. The most common meters are recurring bundles of 2, 3, or 4 beats called measures, sometimes 6, less often 5, 7, 9, or even 33 beats per measure.

Measures are usually in groups of 4 called phrases. Though it’s rare to have a piece based entirely on three- or five-bar phrase lengths, one of the best emotional devices in music is an occasional abbreviated or extended phrase. Nicely messes with your expectations.

The tonic chord usually goes to V or IV, sometimes to iii or vi, less often ii or vii. Mixing the usual with the unusual is the crux of the game.

Different genres of music have certain core instrumentations. A rock band usually has a guitar or two, bass, drums, and vocals. Sometimes a keyboard. Sometimes horns. Sometimes a flute or banjo. Orchestra has ABC, funk band has DEF, polka band has XYZ. So within a certain genre, the choices are even more constrained, and the similarities between pieces multiply.

On it goes, a large but finite set of variables in pitch, meter, rhythm, instruments. The amazing thing is that such an incredible variety of genres and songs has come out of this large but finite set.

Within the choices available are patterns and combinations that produce certain emotional effects — tension, calm, dread, humor, gravity, power, violence, aspiration, momentum, flight. The existing set of musical elements is drawn on over and over by composers to produce these effects in the same way a million writers dip their buckets into the shared well of language, drawing out existing words and phrases and allusions to produce the effects they need.

When writers need to evoke “bittersweet yearning,” they don’t start cobbling together letters into new combinations to see what might feel both bittersweet and yearny. They draw on the large but finite set of words and phrases that have already been used to capture that feeling.

Music works the same way. You want bittersweet yearning? Try a I-iii progression. It’s been done a thousand times, but that doesn’t mean I can’t do it again, a little differently, and create something that is new but (here’s the point) not unique.

The idea that each piece of music arrives fresh from the sea foam like Aphrodite on the clamshell, and that it must evoke no other existing song, is both detached from reality and paralyzing to the songwriter. When I studied composition, I can’t tell you how many times I sat down at the piano to come up with the germ of an idea, plunked out three notes, and said, Nope…Stravinsky. Three more notes: Nope…Bartok. Frustrated silence: Nope…Cage.

It’s a weird modern conceit. Bach did not tinkle out a phrase and mutter, Nee… Buxtehude. Nee…Couperin. Sheiße! Nor did he write music that had already been written. He used and adapted patterns and combinations that almost always had been used before. You use them in new ways, extend them, evolve them — but you don’t set out to utterly avoid every resemblance to what already exists. The whole idea is bizarre. It seems like it’s encouraging originality, but it’s actually deeply anti-creative.

The Case of Stairway v. Taurus

Stairway to Heaven is exactly as “stolen” as everything else you’ve ever heard. When he sat down to write the song, Page drew on existing materials and norms to create something new. Randy California did the same when he wrote Taurus. In the process, they crossed into similar territory for a few bars.

Both started with the commonest clay: 4/4 meter, the key of A minor, and an acoustic guitar outlining the chords in straight eighth notes and four-measure phrases — each choice so common as to be essentially the default.

Then they both chose a device that’s rich and evocative, and not original to either of them: a descending chromatic bass line (going down by half steps). It’s a device so well established that it has a name — the “lament bass” — and variations of it pop up in everything from Bach’s “Crucifixus” to the Beatles’s “Michelle” to “Chim Chim Cher-ee.” Follow that bass line (13 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG6O4N3wxf8″ parameters=”start=7 end=20″ /]

So the descending chromatic bass isn’t default, but it’s a well known device. The question as always is what you do with it. The composer of “Taurus” did this (28 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xd8AVbwB_6E” parameters=”start=44 end=72″ /]

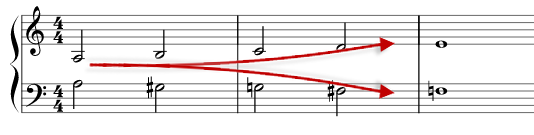

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

As the chromatic bass walks down, A-G#-G-F#-F, see how he keeps returning to the circled notes, C and E? He’s keeping the shape of the A minor triad as the bass walks out of it. That’s nice. Not the stuff of greatness, but nice.

Here’s what Page did with the same bass line (27 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9ioyEvdggk” parameters=”end=26″ /]

That’s greatness. In addition to the descending bass, Page laid an ascending scale into the upper line (circled notes). Sometimes a pitch is displaced by an octave or off the beat, but your ear hears the ascending line. This creates a wedge that slowly opens — unison, third, fourth, sixth, and finally that delicious major seventh — before returning to the unison/octave:

I’ve pulled out the lines so you can hear them better:

The result is a nuanced, haunting passage written by an artist who knew what he was doing. And this doesn’t even crack open the inspired work in the next hundred measures. I might come back to that.

So: was Stairway directly inspired by Taurus? Who knows. In a better world, Page could stand up and say, “That’s right, I got the idea straight from Taurus. Then I made it better. That’s how this bloody thing works.” And composers would stop suing other composers for composing.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Full songs: Spirit, Taurus; Led Zeppelin, Stairway to Heaven

Jimmy Page image by Dina Regine via Flickr | CC 2.0

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

I’m Not Saying Aliens Wrote This House of Cards Cue…

House of Cards is brilliantly scored, soup to nuts. Last month I wrote about the opening title theme. But one cue is even more special — the evocative underscoring that often makes an appearance when Frank and Claire share a cigarette and conspire. It’s called “I Know What I Have To Do”:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/fo781LEHbqc” /]

Apparently it’s special to other people as well: several videos on YouTube will teach you how to play it — an unusual tribute for a background cue. As a bonus, most of them will teach you how to play it wrong (16 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fmchtLg743I” parameters=”end=16″ /]

Nope. Try again (10 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpbAirHi3K0″ parameters=”start=70 end=80″ /]

Sorry, no.

I’m not pointing out these errors to be a pedantic little theorywanker. That’s just a bonus. The understandable errors they’re making reveal something cool and interesting about the piece itself: the fact that it was written by aliens.

You know when kids are first learning to speak, and they say things like, “I goed to the farm and seed the sheeps”? It’s called overregularizing, and it’s actually a sign of sophistication in the learner. Instead of making the daft and pointless transformations from go to went, see to saw, and sheep to sheep, kids regularize all the verbs and plurals to the perfectly good rules they’ve learned, and Bob’s your uncle.

The same thing is going on musically in the errors that pop up when Earthlings try to figure out this House of Cards cue.

In the harmony post, I mentioned that most Western music is based on piles of thirds. Our harmonic language is triads with notes a third apart:

Our ears are used to that map. Give us harmonies based on thirds and our compass points home. The wrong tutorials are “fixing” what they hear to give the illusion of knowing which way is north.

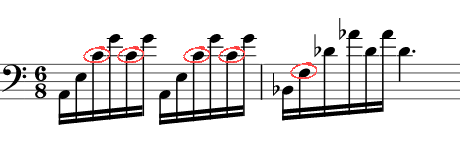

Here’s what the tutorials above are doing (wrong notes circled):

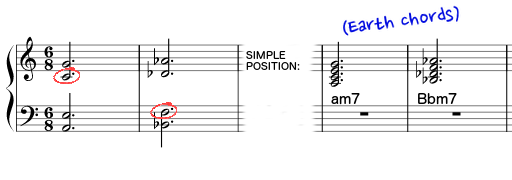

Simplified into chords:

But this House of Cards cue isn’t based on thirds (tertian). It’s quartal and quintal — built with fourths and fifths.

Fourths and fifths are great and common in melodies. The first two notes of Amazing Grace are a fourth, as are the first two of Taps. The first leap in Star Wars is a fifth. They also appear all the time in harmony. But when they do, they are mostly flippable into simple position triads — a pile of thirds, as seen in the perfectly Earthly chords above.

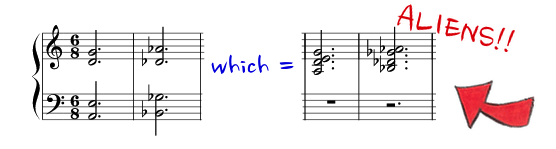

But not this time. This music is unflippably strange:

The notes are now right, which is to say they’re correctly wrong. Musicians, look at that bloody mess. What key has Gb, G, Ab, A, D, Db, and E natural? Then there’s that fourthi-fifthiness. Here it is, simplified:

Look at that! Notes all sticking out to the sides, making Baby Jesus cry. It’s just wrong, even without the right hand melody, which makes it even stranger when added in. But that wrongness is why it’s worth talking about. Compare them side by side now, Earthling first, then alien:

It’s subtle, but believe me, the hairs on your neck know the difference.

Like little kids “fixing” grammar, the tutorials are accidentally adjusting the strangeness into something that makes sense. By budging two notes, they turn fourths into thirds, went into goed, alien music into something we can understand. In so doing, they erase a lot of the eerie quality — that unmoored, homeless fourthiness.

Now sure, you can have fourths and seconds and sevenths and all sorts of other things in normal Western Earth music. But there are rules for how they move to harmonically stable intervals, dammit, and these just aren’t following those rules. They’re sliding from one unstable, unholy mess into another.

By the way, I’ll tell you what compositional technique he used to arrive at this. It’s one I used all the time when I was trying to get outside of the box. It’s called Flopping Your Hands on the Keys to See if the Seed of Something Cool Comes Out. I say this with 99% confidence.

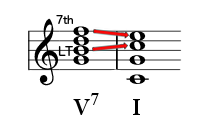

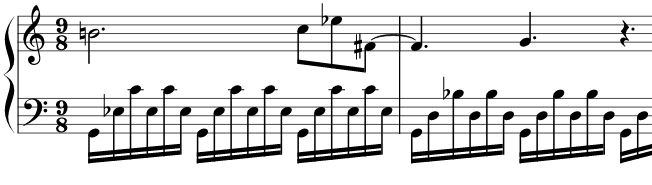

Not true for the next few bars, which suddenly go all rulesy — but it’s the complex harmonic rules of the Romantic period:

Here’s what that sounds like (12 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/fo781LEHbqc” parameters=”start=62 end=74″ /]

Oh my gourd, that is gorgeous. It could have been lifted straight from a Chopin nocturne.

Finally, here’s “I Know What I Have to Do” in scene. Turn it way up:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/0Rqm6dFvDAA” /]

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

The Pitch Ceiling: You Make It to Break It

- June 09, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Unweaving

0

0

Remember 12-year-old Grace VanderWaal on America’s Got Talent? Sure you do.

4:03

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNxO9MpQ2vA” parameters=”end=243″ /]

Give me a minute. I’m a sucker for that kind of thing.

Okay.

I’m not the only one. A friend of mine said she cries at 2:03, every time, and she wanted to know why. First the obvious: Adorable munchkin who has apparently seen Juno 20 times sings about not knowing who she is, then suddenly belts out, “I now know my name!” Dead. I’m dead.

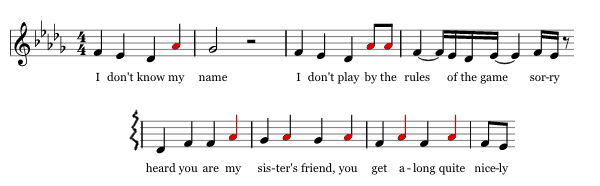

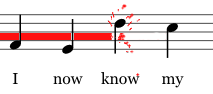

But as usual, it’s not just the words. In the hands of a good songwriter, the music intensifies the meaning of the words. Yeah, the tempo picks up and she sings louder at that spot, but there’s something else there. Over the course of the short song, she creates a kind of pitch “ceiling” — then breaks through it at the perfect time.

Listen to the A-flats (in red below). She keeps hitting that note over and over and doesn’t go above it for most of the song:

The repetition creates a really tangible boundary. Listen:

16 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNxO9MpQ2vA” parameters=”start=76 end=93″ /]

…then her breakthrough in the lyrics is mirrored with a breakthrough in the music, and the crowd responds instantly:

5 sec

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNxO9MpQ2vA” parameters=”start=122 end=127″ /]

That moment was the difference between polite applause and the audience leaping to its feet.

Simon Cowell’s “you’re the next Taylor Swift” comment was a bit much. But if Grace does happen to make it big, she’ll be able to trace her success back to a single well-placed D-flat.

Follow me on Facebook:

Harmony is What Happens to the Hero

As a kid, I knew chords were a lot of notes played at once. And I thought I knew why we had them: Melodies sound too plain by themselves, so we add chords to kind of fill it in, like the background of a painting.

I got better. The relationship between melody and chords (harmony) is much more interesting. We follow the melody like a hero. Behind and around the hero, the harmony provides an unfolding emotional story. It can be a simple home/away/home again story, or more of a leave home, get hit by bus, go to hospital, fall through trapdoor into your own bedroom and discover it was a dream kind of story.

The harmony is not just scenery — it’s what is happening to the hero. To understand how that works, we’ve got to get into the weeds a bit. Bear with me — cool toys are coming, and you’ll need these tools to play with them.

Each basic chord (or triad) consists of three pitches, like words consist of letters. Chords in combination communicate emotion, just as words in combination communicate meaning.

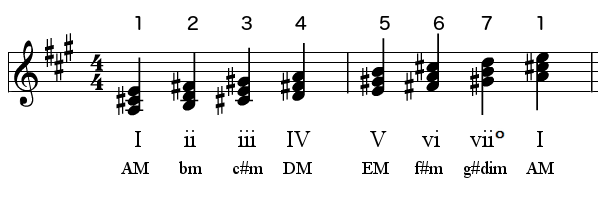

Keys don’t consist of seven notes so much as seven chords (triads). To build those triads, start with the seven notes of the C major scale (plus C again on top):

Now stack pitches on top of them in thirds.

Reminder: From one pitch to the next in the scale is a second, so C to E is a third, as is D to F, E to G, F# to Ab, etc. Doesn’t matter if sharps or flats are involved — it might be a different kind of third (major, minor, augmented, diminished), but it’s still a third:

Start with a note, add a third above it, then add another third above that one. You end up with stacks of three notes on the lines, or three notes in the spaces, like so:

These are the building blocks of musical meaning. Now let me add some information:

If it feels like the first time you looked at a periodic table, steady on — this is easier than it looks. Like the periodic table, it packs in a huge amount of powerful information once you know how to look at it.

The three lines of symbols contain different information about the triads. The digits on top are the simple degrees of the scale itself — the bottom note of each triad, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7, which in C major is C-D-E-F-G-A-B.

The bottom line is what you see on guitar music. These show the pitch on which each triad is based (also called the root of the triad) and the form the triad takes. Uppercase is major, lowercase is minor, and “dim” is diminished (more on that eventually).

The line of Roman numerals is just a way of combining the other two. The Arabic digit (like 5) becomes a Roman numeral (V), and the case of the Roman indicates major or minor. (The little degree circle means diminished.)

We can do the same thing with any starting pitch, any scale. The A major scale has C, F, and G sharped (raised by a half step) to fit the whole-step/half-step pattern of the major scale:

…and so on for any pitch, any scale. The chord symbols on the bottom change, but the Romans stay the same because the chords are fulfilling the same function in each key — the same “words” with a different home (I). I’ll be using the Romans a lot from now on to talk about what’s going on in the harmony of a piece. If I say the chords are I vi IV, it means you hear a major triad built on the first note of the scale, then a minor triad on the sixth note, then a major triad on the fourth note. But instead of 27 words, I use three symbols: I vi IV.

These three-note triads, much more so than the notes of the scale, are the emotional words of music, the bricks out of which everything is built.

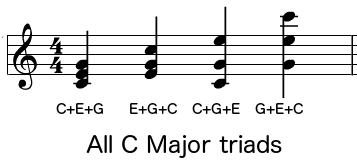

One important point: In the actual music, the notes don’t have to be in that order. They can be exploded out in any order top to bottom. This just reduces it to what’s called simple position, with the notes in the closest possible intervals to figure out what chords they are. Kind of like putting all the letters of a word in alphabetical order, except in music the meaning doesn’t change.

These are all C major triads, for example:

The composer might spread them out like that for different textures and effects. But if I want to figure out what’s going on in the harmony, I can put the last three in simple position with C on the bottom, and their harmonic identity becomes clear.

Okay, back to the triads of C major:

I remember being surprised to learn that a major key consists mostly of non-major chords. But it’s a good thing it does — that variety makes it work, giving you a road map so you know where you are relative to home. And your ear knows how to follow that map. Of course it does — you’ve passed this way ten thousands times before.

As the music moves along through time, left to right, it passes through different chords, and the sequence of chords makes us feel a certain emotional narrative. Same as language: These phrases start with the same three words, but the last three lead to very different places:

- For sale: baby turtles, too cute!

- For sale: baby shoes, never worn.

It works the same in music. Suppose you hear a major chord alone — let’s say it’s an F major triad:

Is that the tonic home? Dunno. It is if we’re in F major. But an F major chord could also be IV in the key of C. Can I get an amen, people:

Or V, the neon arrow, pointing to a Bb home:

In each case, before we could know what the F triad means, we needed another reference point. Once you have two chords, your ear starts to triangulate on home. Let’s say we hear two major triads next to each other, ascending — F major and G major:

When you look at the map for a major key, there’s only one place with two adjacent major chords, one place it fits in the aural landscape — IV to V.

And here’s the crazy great thing. You don’t need to see the map or know the Romans. When your ear hears an F major triad, then a G major triad, your ear instantly knows where home is. Sing it! You know where it’s going! Sing where it’s going, dammit!

C major is home.

So that’s a simple example of starting somewhere harmonically (F) and ending up at different homes (F, Bb, and C). That’s the tip of the tip of the iceberg. Composers use these ambiguities to mess with you, moment to moment, leading you to expect one direction and giving you another. It’s like those “garden path” sentences:

- The old man the boat; the young watch from shore.

- The man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

- The cotton clothing is made of grows in Mississippi.

- Mary gave the child the dog bit a Band-Aid.

Back to music for a while, including some unweaving that goes further into the harmony/hero relationship.

If you’re new here, or you want to review, you can start at the first post, or work your way through Just Enough Theory in the right sidebar. Quick and fun.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!