The Hidden Grammar of Music

I was 13 when I saw my brother’s college music theory textbook sitting on a table — Walter Piston’s Harmony. I had played clarinet and sax for a while, even did some arranging for jazz band. So I knew a little theory, but I was barely out of the blocks.

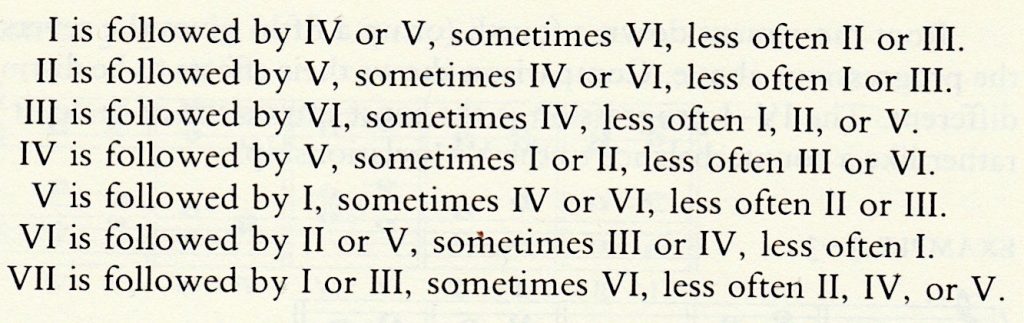

When I picked up the book, it fell open to a section called “Table of Usual Root Progressions.” Clickbait! I traced the words with a trembling finger:

Whoa.

If I’d known less theory, I’d have glossed right over it without understanding what it meant. If I had known more, I might not have been surprised by it. As it happens, I knew just the right amount to be gobsmacked.

It continued:

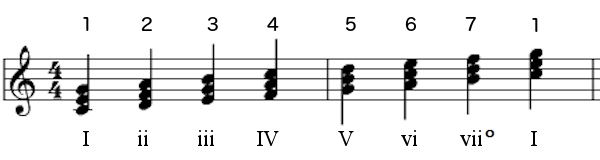

Here’s what it’s saying. Every key has 7 triads in it — 7 chords based on the 7 notes of the scale for that key. This is C major:

Now look down the left side of the Piston text: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII. These are the 7 triads of any key. (If you know some theory or read this post, you’ll know the Romans are usually upper case for major and lower case for minor. He’s making them generic for this example. Be not confused.) Each line is saying, “When you hear this chord, here are the chords you’ll most likely hear next.”

So for C major, you could rewrite the text like so:

The C triad is followed by F or G, sometimes A minor, less often D minor or E minor.

The D minor triad is followed by G, sometimes F or A minor, less often C or E minor.

And so on.

Here’s the thing: I had no idea there was a “most likely” order of chords. If I’d written a theory book when I was 13, it would have said

Chords are nice because they make the music fuller than just a tune alone. If you’re in the key of C major, the C triad should be followed by something different, because variety is the spice of life. GENESIS RULES! DM + KH 4EVER

I saw the chords as 7 different colors the composer could use, and yes, they are that. But it never occurred to me that there was this kind of hidden sense to it, a kind of grammar, like saying The subject is usually followed by a verb, sometimes by an adverb, less often by a prepositional phrase.

It was my first real glimpse below the surface of music. And then Piston did something lovely and rare in music theory — he explained why it’s that way.

When you move from any triad to another, there are only three possibilities: the chords have two shared notes, or only one, or none at all: Each of these has a different emotional quality. The first one is called a “weak” progression (though never to its face) because there’s only that small change between the chords, just one note different while two hang on. It’s like a sloth working its way through the forest canopy, moving just one limb at a time while the others stay attached.

Each of these has a different emotional quality. The first one is called a “weak” progression (though never to its face) because there’s only that small change between the chords, just one note different while two hang on. It’s like a sloth working its way through the forest canopy, moving just one limb at a time while the others stay attached.

When the roots of the chords (the note on which it is built) are a third apart, like C to E, you get that progression.

“Weak” doesn’t mean bad — sometimes a weak progression is just what you want for a tender moment, like so:

Here it is put to perfect use:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/J6xzL0TrsRY” parameters=”start=67 end=78″ /]

If all of the notes change, the feeling is more abrupt. There’s no connection between the chords. There isn’t a sense of smooth harmonic direction because the connection to the previous chord isn’t there. It’s a monkey leaping from one tree to another. You can’t easily tell where he leapt from.

When the roots of a chord are a second apart, like C to D, you get this kind of progression. The chord change at 0:38 is this type:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/eQAm7eZr920″ parameters=”start=17 end=45″ /]

And then there’s the engine that drives music. This is for chords with roots a fifth apart, like G and C, dominant to tonic. It’s Goldilocks, not too weak, not too abrupt: one note shared, two notes changing. It’s the perfect balance of continuity and dynamism, the monkey brachiating effortlessly through the rainforest of your mind, one hand back on the previous branch, a hand and a foot reaching forward to the next. And on he swings.

It’s called a circle progression for a great reason I’ll get to eventually.

When a composer wants you to feel direction on a large or small scale, the circle progression is the go-to. It flows like water. This aria from a Bach cantata is as good an example as any. The circle starts at 0:17 and ends around 0:30.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/3rKIc6QBCig” parameters=”end=31″ /]

Do you feel how the harmony was essentially marking time at the beginning, then starts rolling forward at 0:17? Circle progressions will do that to you.

The big news here is that harmony is spinning out a narrative beneath the melody. Composers use a mix of the three types of progressions to create an ebb and flow — moving forward, circling back, pausing, lurching, and sliding effortlessly in turn.

Now if you look back at the Piston text, it starts to make sense. No matter which of the 7 chords you’re on at a given moment, the most likely next step is a circle. That Bach progression is

I – IV – VII – III – VI – II – V – I

That’s all circle, and you can feel the tumbling momentum. But sometimes you don’t want that, so you’ll move by second or third, depending on the musical need of the moment.

Like all grammars, the real fun comes in busting out of the box — chromatic harmony, secondaries, modal harmony, polytonality, atonality, jazz harmony — but that page of Piston’s Harmony was my first step into the basic grammar of Western music. And it totally changed the way I saw my favorite thing.

Follow me on Facebook:

What Happens When “Happy” Goes Minor?

- November 06, 2016

- By Dale McGowan

- In Ruined

0

0

Major is happy, minor is sad. It’s the one music theory thing that everybody knows. But what happens when you cross the streams, taking a major song and throwing it into the soul-crushing abyss of a minor key?

That’s just what Chase Holfelder’s Major to Minor project does, turning upbeat numbers like “Kiss the Girl” from The Little Mermaid into a creepy assault fantasy, and making the sweet tribute to undying love that is “I Will Always Love You” into a soundtrack of dark obsession (20 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/_xz10ZNNkoM” parameters=”start=113 end=134″ /]

But there’s one pretty obvious target that Chase hasn’t transmogrified yet — a song so happy that its actual name is “Happy.” So I wonder what happens if you take Pharrell Williams’s infectiously danceable hit and put it in a minor key?

I’ll tell you what happens. NOTHING happens — because “Happy” is already in minor.

[arve url=”https://giphy.com/embed/g1a84q6RBSMrS” /]

You don’t believe me OR Anna Kendrick? Fine. First a taste of the original, then I’ll wreck it to prove my point (24 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y6Sxv-sUYtM” parameters=”start=11 end=36″ /]

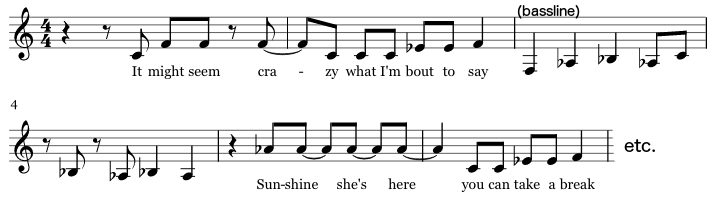

If you read music, you can see it on the page. The F minor scale has Ab, Db, and Eb — F major does not:

Straight up F minor.

Now there is a little major cream in the minor coffee of this song, a few A-naturals peeking through here and there. It’s a common practice in jazz and R&B to let major and minor knock up against each other. But there’s no doubt that minor wears the pants in this one. If I scrubbed every little fleck of major from “Happy,” turning it all minor, you’d hardly notice the difference. Turn it all major, though, and the song is destroyed.

Lemme crank up my quaint Korg M-1 to do a reverse Holfelder, switching “Happy” from minor to major. Here’s the opening:

Gah. It’s like the Partridge Family at its whitest.

Even worse is what happens to this spot, where the backup singers sing “Happy, happy, happy, happy…” (12 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/y6Sxv-sUYtM” parameters=”start=121 end=132″ /]

Here it is in F major:

Okay, so “Happy” is minor. But how can that be? How can anything as happy as “Happy” be in a minor key?

The answer is that emotion in music isn’t on a simple major/minor toggle. A lot of variables are in play. In his remixes, Holfelder never only changes the mode to minor — he messes with tempo, instrumentation, dynamics, vocal stylings, and chord structures as well.

This goes both ways: By fiddling with other switches, music in a major key can be just as sad as minor. This devastating number from Les Miz is in a major key:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/86lczf7Bou8″ /]

And aside from sad, a minor key can be powerful, goofy, thrilling…and yes, even happy.

Don’t miss a post! Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook…

The Masterpiece I’d Never Heard Of

During the 2016 US presidential campaign, Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson was asked on national television what he would do about Aleppo as president. When he said, “And what is Aleppo?” my heart lurched. And when the interviewer said, “You’re kidding,” then spelled out the centrality of Aleppo to the crisis in Syria as if Johnson had revealed himself to be a small, dim child, my lurched heart collapsed like a dying star.

It took me back to a moment in my doctoral program when I sat with five other candidates for the Ph.D. in music in the withering glare of an astonished professor. She was a brilliant composer with an encyclopedic grasp of All Human Knowledge, or so it constantly seemed, and a mission to ferret out the ignorance of others, often publicly, with unforgettable shock and zeal. And hey, a Ph.D. represents a capstone endorsement of mastery in a given field, so such ferreting is not without purpose. But she felt that subject mastery should be accompanied by general mastery. Again, I agree — brilliance in one field accompanied by ignorance in most others isn’t a great educational outcome. But there are side effects of this kind of prolonged trial by fire, and for many years afterward, I struggled to shake a really bad habit: the inability to admit that I didn’t know something. ANYTHING.

Back to the withering glare, which was deployed when she realized that none of us knew the name H.L. Mencken.

I later discovered Mencken and became a great admirer. But when she read a Mencken quote in the seminar, the name rang no bells. Sensing this, she said, “And H.L. Mencken is, of course…?”, I sat in silent, rising horror with my classmates, knowing what would come.

A gasp.

“H.L. Mencken??”

Her eyes inflated and met each of ours in dramatic turn. Another gasp.

“H.L. Mencken H.L. MENCKEN???”

“A writer?” someone guessed desperately.

“American or British? American or British???”

“Uh…American?”

“Critically. Important. Influential. Early. 20th. Century. American. Journalist. And. Satirist. H. L. Mencken.” She exhaled in disgust. “You should know H.L. Mencken.”

But we didn’t. And worse, now she knew we didn’t.

In addition to good things, grad school is an extended exercise in hiding what you don’t know. You first learn to hide it from those who hold your future in their hands, then quickly generalize the habit to all humans. When someone asks a grad student in music if he or she is familiar with a certain composer, performer, conductor, stylistic movement, or piece — or in this professor’s case, writer or activist or medieval Estonian peasant revolt — the graduate student will answer with some version of, “Yes, of course.” Every time.

If the student actually knows it, you might detect this slightly enthusiastic leaning-forward, an eagerness to share. If he or she has never heard of it, the “Yes, of course” will be accompanied by a facial expression that says, “I seem to have swallowed a cockroach.”

S/he’s worried that the thing in question might be so well known to the asker that saying “Never heard of it” will seem as bad as if the question had been, “Are you familiar with the letter E?”

Next time you’re around a grad student in music, say, “I just adore the late quartets of Johann Mamflamheim, don’t you?” When s/he says, “Yes, of course,” ask which one is his or her favorite and why. Real entertainment ensues. The game is adaptable to all fields of study.

This professor lived for that kind of reveal.

The oral preliminary exam near the end of a Ph.D. program is the culmination of this dynamic. You sit around a table with your doctoral committee — usually 4 or 5 graduate faculty members — and they grill you unsmilingly for two hours. The purpose is to test the comprehensiveness of your knowledge of the field. If you fail to demonstrate sufficient mastery, in their sole judgment, you are dismissed from the doctoral program and may not re-apply.

My Ph.D. area was music composition. A year before the oral prelims, I asked my grad advisor what I could expect. “It’s not pleasant,” he said. “That’s by design. They will try very hard to rattle you. They want to reveal what you don’t know and see how you handle that.”

Mm. “Should I expect theory too, or just composition?”

He looked at me over his glasses. “The subject is music. Music as a human endeavor in all places and times. Absolutely everything is game.”

I spent that year in intensive gap-filling. I scoured the Harvard Dictionary of Music for unfamiliar terms. I refreshed my knowledge of medieval modal theory. I listened to hundreds of hours of music in every culture and genre. Classical, jazz, Balinese gamelan, Indian carnatic microtonal singing, shape note singing, Tuvan throat song, and the insane piano rolls of Conlon Nancarrow. I read histories and analyses and theory journals.

Two days before the exam, riffling through some journal, I saw a passing reference to a piece called The Infernal Machine, written by Christopher Rouse in 1981. An example of the mechanistic movement of composition in the late 20th century, in which musical instruments were used to evoke machinery. I’d never heard of the piece, the composer, or the stylistic movement.

I filed the information in my head.

Two days later I was sitting before the committee, waiting for the first question.

“I’ll begin,” said the Formidable One. “Mr. McGowan, what can you tell me about the mechanistic movement of composition?”

I am not kidding. I nearly passed out.

“The mechanistic movement,” I said steadily, “was a late 20th century experiment in which musical instruments were used to evoke the sounds of machinery.”

“Excellent,” she said. “Name a representative composer.”

“Well there’s Christopher Rouse, of course.”

“Of course. And a piece by Rouse that can be rightly called mechanistic?”

“The Infernal Machine.”

“Excellent!” She was determined to find the edge of my abyss so she could place her fingertips on my chest and shove. “And the year The Infernal Machine was composed?”

I paused, pretending to search deep in my files for what was actually still on a Post-It note flapping perilously in the breeze on my prefrontal cortex. “I believe that was…1981.”

She slammed a hand on the table. “Yes! Excellent!”

This is not a story of celebration, you understand, not even slightly a brag. This was stupid luck, a bullet dodged. I can only guess how the rest of the prelim would have gone had I whiffed the first pitch. The nature of such exams is to build a mighty snowball around any small core of found weakness, which underlines the basic lunacy of the assumption that a person can be in full possession of knowledge, even in one field of specialization, Herself excepted.

Fast forward to now. I’m reading a great book called Listen to This by Alex Ross, music critic for the New Yorker, a collection of essays about music covering an amazing range of topics from Schubert to Radiohead.

In the Radiohead chapter, guitarist Jonny Greenwood is quoted as saying “I heard [Olivier Messiaen’s] ‘Turangalîla Symphonie’ when I was fifteen, and I became round-the-bend obsessed with it.” That kind of thing is always fun, like finding out Yo Yo Ma loves bluegrass.

Twenty pages later, in a chapter on the Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen (yep, say it out loud, I’ll wait: ), we get this:

It was the experience of hearing Messiaen’s sublimely over-the-top Turangalîla, at the age of ten or eleven, that inflamed his desire to compose.

Well that’s funny. Two very different musicians had their minds nicely blown by Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphonie before they could drive.

Oh, and here’s an interesting thing about the Turangalîla Symphonie: I’D NEVER HEARD OF IT. I didn’t even know much about the composer, and I certainly would have remembered the name of that piece.

I have a thousand files in my head with information about music. The J.S. Bach file has bio on the surface, then continues down through elements of style (and why), favored genres (and why), impact on the course of European music including specific influence on key composers of the following generations, and a thoroughgoing catalog of works, including an ability to sketch the full 32-movement structure and harmony of the Goldberg Variations on the back of a napkin after three pints. I could pick out his handwritten music notation from a lineup. I ran the whole C minor Passacaglia through my head as I sat in the Thomaskirche where he worked and is buried. I know Bach and a hundred others inside and out.

But my Messiaen file looks like this:

MESSIAEN, OLIVIER (sp?)

French composer, 1940s. Catholic. Wrote ‘Quartet for the end of time,” a lot of long notes. Liked birds.

On one level, the details are trivial. They aren’t what ultimately makes for mastery. But they are the brown M&Ms of knowledge: If those surface details are wrong or missing, it probably indicates rot down below.

If the Formidable One had asked me to name any two pieces by Messiaen, I’d have been screwed. But here were two musicians of very different traditions who had come across and been deeply influenced by a massive orchestral piece of his that I’d never even heard of, even after completing a Ph.D. in composition and teaching music history at the college level for 11 years. And they knew it when they were 10 and 15.

But here’s the thing: after years of recovery, I’m apparently okay with that. Until now, I’d never heard of it. There, I said it out loud. Never heard of it.

If you find yourself in possession of 80 minutes and a sense of adventure, here’s the massive, weird rollercoaster of the Turangalîla Symphonie by Olivier Messiaen.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PjyCpRKDrk” /]

Even for Messiaen, the Turangalîla-Symphony is weird. Rather than the usual rapt mixture of birdsong, plainchant and Catholic theology, here we have dancing rhythms, tantric sex and laughing gas. — Phil Kline

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

Why is That iPhone “Don’t Blink” Ad So Damn Cool?

I don’t care about the headphone jack. Listen to the music:

Almost every part of the ad score is variations on a single rhythm — that Bump. Bump. Bump, bump, a-CHAK you hear in the opening seconds. It’s a cool rhythm. But what’s cool about it?

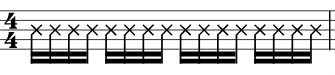

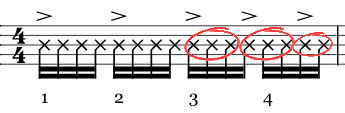

It’s not pitch. This is mostly about rhythm, the division of time into bits. If you have four beats per bar and divide each of them into four 16th notes, you can think of the bar as having 16 available slots. In each one, you have a choice: hit the drum, or hit it hard (accented), or do nothing. 16 slots, 16 choices in each bar:

Just as melody and harmony draw on 12 available pitches, most rhythm (in 4/4, the most common meter) is created from grouping these 16 clicks. In this case, it’s 4+4+3+3+2:

1234 1234 123 123 12

Two groups of 4, then two groups of 3, then a group of 2. This has the effect of establishing a steady beat (1234 1234), then throwing you off balance a bit (123 123 12), then returning to steady in the next bar (1234 1234). On top of that, there’s a feeling of acceleration as the groups get shorter.

The combined result is two confident steps, then trip-tumble forward a little, then a smooth recovery into the next measure.

Okay, bad example. More like this:

We’ve been here before, in the post on The Evolution of Cool:

Our cerebellar timekeeper determines how regular a sound is. If it stays predictable — dripping water, chirping crickets — we feel confident and secure. If it becomes less predictable or changes in intensity, we feel unsettled, possibly threatened.

The beats [of a Sousa march] are regular. Your cerebellum is tapping its foot, predicting every beat, right on the money. It makes you feel safe, confident, in control, but no one would call it cool.

The Sacrificial Dance from The Rite of Spring is jerky and angular, with unpredictable rhythms and sudden changes in intensity — the musical embodiment of anxiety and terror. Your cerebellum is freaked out by the utter inability to predict the next note. The music is doing what it’s supposed to do, but you wouldn’t call it cool.

The music we identify as cool splits the difference, combining a steady predictable beat with unpredictable departures from that beat. It’s flirting with the remote sense of danger without actually endangering you.

If music establishes a beat, then throws you around a bit — backbeat accents, unexpected hits around the beat, changing patterns — it gives a little thrill to your cerebellar timekeeper, tickling that part of you that listens for the irregular sounds of danger, then pulling you back to the safety of a steady beat before dangling you over the cliff again.

The ad throws a few extra stumbles in to keep you off balance on the larger scale. Start tapping right at the beginning and keep it rock steady. You’ll feel yourself trip over a notch in time around 4 seconds:

Feel that?? One extra 16th rest was inserted, a single click in time, throwing you behind the beat. That gives your cerebellar timekeeper a little thrill. That’s cool.

Yeeeah, Something’s Gonna Harm You – Sweeney Todd

5 min

Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd just reappeared on Netflix streaming, and within two days I had a reader question about it:

Q: In Sweeney Todd, at the end of the scene where Toby sings Nothing’s Gonna Harm You to Mrs. Lovett, she sings it back to him, but the music is suddenly making my flesh crawl when she does. What the heck is going on?? – Wendy T.

Oh Wendy. I know the scene.

The music in Sweeney Todd is phenomenal and the lyrics among the most inventive Sondheim ever wrote. And that’s saying something for the guy who came up with

I like the isle of Manhattan

Smoke on your pipe and put that in

THE SCENE: Little Toby has realized Mr. Todd is up to no good, and he’s worried about Mrs. Lovett, without whom he’d be living in a Dickens novel — and not the What-day-is-it-today, delightful-boy, bring-me-that-goose-and-I’ll-give-you-a-shilling part.

Toby sings “Nothing’s gonna harm you / Not while I’m around” to a trite melody that mirrors his naiveté. We know something that Toby does not: Mrs. Lovett is a willing accessory to Sweeney Todd’s crimes, guilty right up to her meat pies.

While Sweeney has been driven to a murderous spree by a missed chance to kill the judge who ruined his life, Mrs. Lovett is only in it for the filling. So when Toby goes all Oliver Twist on her, you can see her soften a little.

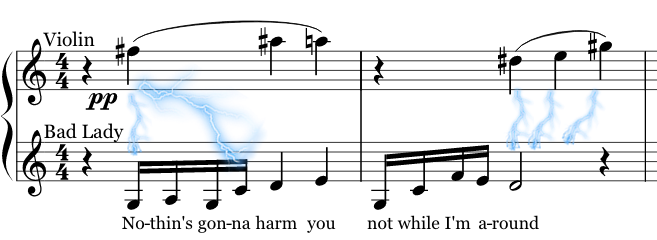

Mid-scene, Toby sees something that confirms his suspicions about Mr. Todd — the coin purse of his missing and presumed-dead master — and he flips out. To calm him, Mrs. Lovett sits him down and sings the same protective song that Toby sang to her. But we know, from the music alone, that she has decided to kill the boy.

Watch the whole scene for the full effect. The skin-crawl starts at 2:48:

3:25

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/LssWKaDF9bk” /]

What’s Going On

The music is identical to Toby’s song with one addition: a quiet violin line high above the voice. While Mrs. Lovett is singing in C major, the violin is playing an atonal melody, meaning the notes don’t really fit into any key — the musical equivalent of insanity. As a bonus, the particular notes he chose are creating strong dissonances with the melody — ninths, sevenths, tritones.

Sondheim doesn’t need to hit you over the head — just six quiet disordered notes tell you how different Mrs. Lovett’s thoughts are from her words. If the lines were in the same octave, it would be harsh and unsubtle. By instead putting two octaves of air between them, Sondheim makes your skin crawl.

Is there a piece of music you love or hate but don’t know exactly why? A moment that makes you laugh or cry? Be like Wendy. Submit a question here!

Click Like below to follow on Facebook…

When Truman Touches the Wall

15 min

The climactic scene in The Truman Show is so intensely satisfying that it still stuns me after all these years. One musical technique plays a big part in that.

Non-harmonic tones are notes that are not part of the chord of the moment but still make sense because they follow certain patterns. The non-harmonic tone that makes the climax of The Truman Show so devastatingly perfect is a pedal point (or simply ‘pedal’).

The rule for a pedal is simple: A note starts out as part of a chord, then it doggedly hangs on, even as the chords change around it. You’re still hearing that same note, maybe held out long, maybe pulsing in quarters or eighths. Sometimes it’ll belong to the chord and sometimes not, but regardless, it keeps sounding. That’s a pedal.

Tom Petty uses a double pedal all the way through Free Fallin’. Two notes are unchanging in the guitar, C and F, ringing straight through the song even as the chords change around them (39 sec):

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lWJXDG2i0A” parameters=”start=3 end=42″ /]

Sometimes it’s just a nice effect. But a pedal point can also serve the emotional purpose of establishing reality, for better or worse — a steady insistence that we accept the situation.

One of the most stunning uses of a pedal point was in the recessional at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, a piece called “Song for Athene” by John Tavener. Listen to the low F in the basses (same note as Free Fallin’). It starts right at the beginning. Better still, hum along with that long note in any octave so you can feel the music moving around that unchanging core, moving between minor and major, dissonance and consonance, darkness and light. Go all the way to 5:44 if you can — it’s one of the most profound musical settings you’ll ever hear, especially if you hum that pedal all the way:

There was a feeling of unreality when the news of Diana’s death first broke. It seemed somehow impossible. Tavener’s pedal had the effect of cementing our acceptance: Oh my God, she really is dead.

Now listen to the end of The Truman Show. The pedal begins at 1:00, those steady quarter notes down in the low strings, but don’t skip that first minute to set it up:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gn5kuDdeGzs” /]

We spent the film watching Truman struggle with uncertainty and confusion, wanting answers. When his hand touches the wall, he finally has his answer — and the pedal, the music of finality, tells us it’s true.

Follow Dale on Facebook…