The Fifth Beatle Was a Robot

One of the most amazing things about (Western tonal) music is how much variety has tumbled out of a few basic materials. Twelve pitches in four triads in two main modes, maybe ten basic rhythms and a half dozen common meters and 20 instruments — shake well, and out pours Danny Boy and Mozart’s Lacrimosa and So What and Uptown Funk and the Nokia Tune and Sacred Harp 457 and madrigals and national anthems and this and this and god help us Happy Birthday. Millions and millions and millions of unique pieces created by repeatedly dipping a pan into the same stream, then picking through the nuggets.

What distinguishes one genre from another, or one composer or band from another, is the choices made among those nuggets. Handle harmony and rhythm and timbre in one way and you’re Bach, another and you’re Brahms, another and you’re nobody. Same with pop music. The reason you can tell the Stones from Coldplay is largely about the different approaches they take to the elements of music.

Scientists at SONY CSL Research Lab fed huge amounts of data from Beatles songs — choices made in harmony, melody, instrumentation, etc — into an algorithm that then composed a “typical” Beatles song. Uh…enjoy?

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSHZ_b05W7o” title=”Daddy’s Car: A Song Composed by AI” /]

It’s a little uncanny in that slightly queasy way, but I’ve got to admit — the essence is absolutely there.

So what is it that’s so bang-on Beatles-y?

There’s that rhythmic flow that starts at 0:05 (quarters in the drums, dotted quarter/eighth in the bass, eighth note strum in the rhythm guitar), the falsetto background vocals, the George Martin tubular bells, trippy background voices, all Beatles favorites. All good stuff. But it’s the harmony that our robot overlord has gotten (if I may say so, Your Excellency) exactly right.

[Be advised that the following includes theoryspeak. If that isn’t your thing, just listen at the times provided. You’ll get the idea.]

The drifty ahhhhh at the very beginning makes a slippery diminished triad. Which way is up, where is home? It doesn’t much help when the full harmony comes in (0:05): First there’s a triad that isn’t a triad (B C# F#), then an F# major triad, then A minor. It’s still hard to know where home is because no key contains both F# major and A minor chords. Then suddenly, boom, we’re in the key of B minor at 0:12, though the progression that follows is not at all typical.

We modulate to A minor (0:39), then to G major (0:47). A and G are close to B and to each other on the keyboard, but they are on different planets harmonically. So we have not only crossed into three different keys in under a minute, but three wildly unrelated keys, and gracefully at that.

Starting at 0:47 we get a progression that is all Beatle: G-A7-C-G, or I – V7/V – IV – I. Just listen to 0:47-1:07 and try to think of any other band. Then keep going a few seconds for the very cool jump back to B minor at 1:09.

“Down ON THE ground” (0:39- ) might be the most Beatlish spot in the whole thing. “ON” is a non-chord tone called an appoggiatura — a leap to a note that’s not in the chord, then a step in the opposite direction to resolve, something in a lot of Beatles songs — and it’s over a descending chromatic scale in wavery guitar, another fingerprint of theirs.

So if you wonder what made The Beatles The Beatles and everyone else everyone else — it’s mostly about the harmony. Sure, they wrote some four-chord pop songs. But the songs that really left a mark include harmonic adventures that no one else even approached. And even if you don’t know a thing about theory, you can hear it and feel it.

If you are fuming about the idea of a computer performing a credible facsimile of the human creative process, take heart. It’s easier to imitate than to create an original piece of genius. No robot has written the equivalent of “Eleanor Rigby” or “Because.”

Yet.

Click LIKE below to follow Dale McGowan on Facebook!

The Real Inspiration for The Simpsons Theme – And No, It’s Not ‘Maria’

5 min

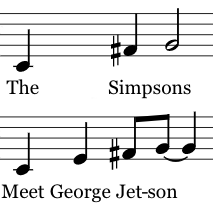

When in the last post I suggested that a trumpet lick in The Simpsons was an homage to “Something’s Coming” from West Side Story, I didn’t mention an even more obvious parallel — that the first three notes of Simpsons exactly equal the first three notes of the main melody of “Maria”:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpdB6CN7jww” parameters=”start=39 end=42″ /]

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1r2EbNSymjE” parameters=”start=2 end=5″ /]

Here’s why I left it out: Unlike the trumpet lick, the opening of the Simpsons theme was definitely not inspired by “Maria.” Elfman was paying tribute to something, but it wasn’t West Side Story. It was The Jetsons.

Back in the 1990s, if a producer really really liked a composer, he would give him a mix tape. As The Simpsons was in development, Matt Groening gave Danny Elfman a tape with all of his favorite cartoon music. He loved the music for Warner Bros. cartoons and Tom & Jerry, but he didn’t want to use that technique known as “mickeymousing” in which the music closely parrots the action on screen. That left Hanna Barbera, including Groening’s favorite cartoon theme of all: “I loved The Jetsons theme the best,” he said.

In no time, Elfman cranked out an iconic theme with a headmotive that bears a striking resemblance to his boss’s favorite:

Also not a coincidence: both are in that unusual Lydian dominant mode I banged on about last time — 4 up and 7 down.

Oh but that’s not all. The whole Simpsons opening sequence is an inside-out parody of The Jetsons opening sequence. In The Jetsons, you start with blue sky and Dad driving away from home. Two kids go to school, then Mom goes shopping, then Dad arrives at work. In The Simpsons, you start with blue sky and Dad driving FROM work, Mom leaves the store, the kids leave school, and they all converge at home.

Both openings are below. For maximum fun, play them at the same time. For more convincing, listen to the short Groening interview below.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1r2EbNSymjE” /]

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eSptqzfTSSE” parameters=”start=8 ” /]

Here’s the smoking gun:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UthzUr0rFQ” /]

Feature image Ludie Cochrane CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Could it Be? Yes It Could! Simpsons Coming, Simpsons Good

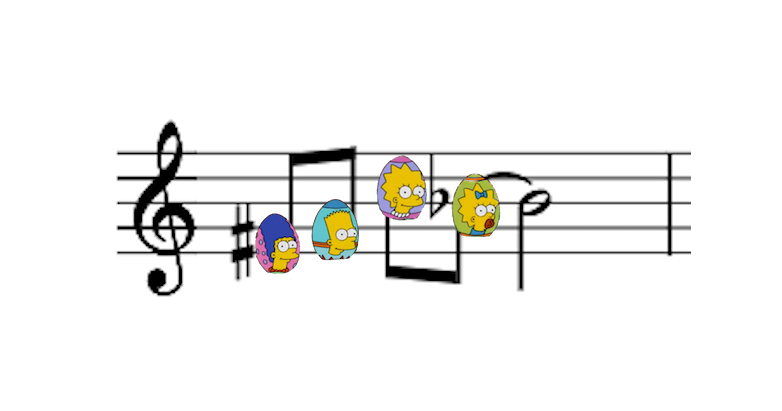

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

There is an Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

It jumped out at me the first time I saw the show, probably 1990, and I was immediately convinced that composer Danny Elfman meant to do it. This morning I decided to find his email address to ask him.

In the process of looking for his email, I learned that Elfman’s violin concerto Eleven Eleven just premiered at Stanford’s Bing Hall, and realized that asking him about the goddamn Simpsons theme is like saying “Hello? Is it me you’re looking for?” into Lionel Ritchie’s answering machine, and I recognized that The Simpsons is the equivalent of a catchphrase for Elfman, a good thing that you spawned long ago that continues to nip at your heels for the rest of your life, and that asking about The Simpsons instead of Eleven Eleven in 2018 is like walking up to De Niro on the street and saying, “You talkin’ to me?” and thinking one’s self very clever, so I stopped looking for his email address.

But still, there’s this Easter egg in the theme for The Simpsons.

First you need to know that The Simpsons theme is not in major or minor. It’s in a mode called Lydian dominant. Start with a major scale, then raise the fourth step and lower the seventh, like so:

You’ve heard music in some form of Lydian mode a million times, mostly in movies and musicals. It tends to convey goofiness when fast, childlike wonder when slow. The Simpsons is an example of the fast and goofy; here are two from the childlike wonder department:

(8 sec)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sZTbn97-Wws” parameters=”end=08″ /]

(16 sec, and you’ll wish for more)

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_t98LWNwUhI” parameters=”start=96 end=113″ /]

Now to the Easter egg. It’s the trumpet lick at 51 seconds:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xqog63KOANc” parameters=”start=51 end=53″ /]

A very distinctive little motive, innit, including both of those unusual Lydian dominant pitches. In fact, I’m pretty sure I’ve only heard that exact thing in one other place. Listen to Tony from West Side Story when he sings the words “maybe tonight” twice at 2:43:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xu7sRdRrm_w” parameters=”start=162 end=169″ /]

Those exact pitches in that exact shape and rhythm, appearing by chance in The Simpsons? Naw. It’s homage, I tells ya, homage. But only Danny Elfman knows for sure, and I’m not asking.

On Solving the Musical Mystery of My Life

- March 14, 2018

- By Dale McGowan

- In Emotion

0

0

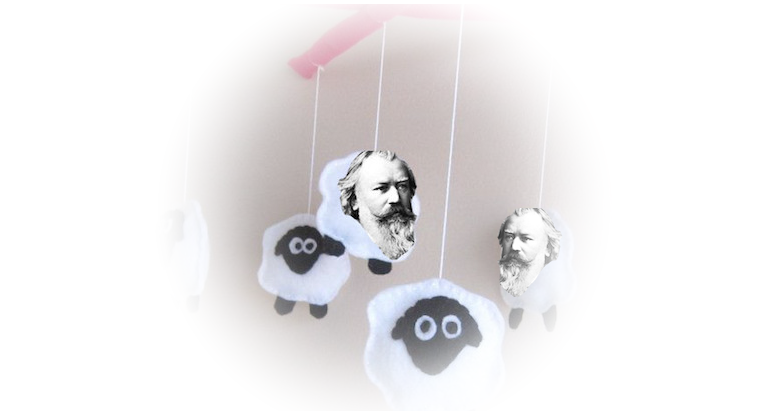

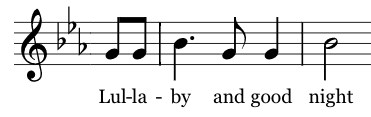

Ever since I was a wee babe, one song made me spontaneously burst into tears — Brahms’ Lullaby (“Lullaby, and good night,” etc.). My parents first discovered this because the mobile above the crib played it, and every time they wound the infernal thing up, I’d shriek until it stopped.

For at least the first 20 years of my life, just a few notes of Brahms’ Lullaby would draw a convulsive wet snurk from my face. My brothers loved this and would miss no opportunity, ever. In the middle of a long, quiet car trip, Older Brother would quietly hum the first few notes so only I could hear, and I would thump him, and I’d get in trouble, which was So Unfair. Even worse were the times Younger Brother made me cry, which disrupted the whole Order of Things.

Worst of all was the fact that I didn’t know why it did that to me. It was bizarre.

Barber’s Adagio for Strings (as I may have mentioned) also makes me cry, but that one slays me gradually for reasons I can explain. The Brahms was always immediate and impossible to account for. My family advanced various theories, my favorite of which was that I was the reincarnation of Brahms’ wife and I missed him. But if that were the case, I figure the Academic Festival Overture would also choke me up.

I’m over it now, mostly, but I never stopped wondering what that was all about. I even tore apart the theory of it, which in this case was like tearing into tissue paper: it’s all I and V and IV with nothing more adventurous than a couple of passing tones in the melody. Shocking modulations and searing appoggiaturas are pretty thin on the ground in lullabies.

My older brother suggested it might be the recurring minor third motive:

the shape of which does rather imitate the Universal Taunting Melody (“Nanny Nanny Boo Boo,” BWV 386b):

I like that idea, but I suspect being bothered by the UTM requires a level of emotional registration that was still in my future at that point. And though I’d have put my figured bass harmonizations up against any other toddler in South St. Louis in 1965, my motivic analysis was still sub par.

And then, a few days ago, more than 50 years after first blood, I suddenly solved the musical mystery of my life. The answer was so obvious that I’m a little embarrassed, especially since you figured it out in the first paragraph, didn’t you.

My parents would wind up the mobile, start the tune, and then leave.

That has to be it. Brahms’ Lullaby was my soundtrack of abandonment. As I cried, that melody tinkled above me. Later, I’d hear the tinkle and the tears would flow.

This would have been solved 30 years ago if I’d stuck with the psych major, but I went into music theory. So like the guy who looks for his wallet under the streetlight instead of back in the alley where he dropped it because the light is better, I spent all those years hammering a nail with a screwdriver because…uh, the light was better.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=46eJ6OoATRg” /]

Follow on Facebook:

Why Does Surf Rock Sound Vaguely…Middle Eastern?

12 min

Most musicians have a mild hatred of scales because we were all forced to practice and memorize them without anyone ever telling us what the hell they are.

I mentioned before that a scale is the palette of pitches with which a specific piece of music is painted. If you’re a composer in the West, you generally go into a paint store of 12 available pitches (the chromatic scale) and choose a subset of pitches for the emotional quality you want, essentially a palette of colors for the piece. Most of the time we choose one of two palettes: major or minor. It’s amazing how much great music has come out of those two palettes.

Once in a while we alter a single pitch to make something like the Dorian mode (Michael Jackson’s favorite, which takes a minor scale and bumps the sixth pitch up a click). If you change more than that, the scale begins to sound exotic, and that’s especially true if you create a step that’s not present in major or minor. The second step of the scale, for example, is a whole step above the tonic pitch in both major and minor, like the do-re in do-re-mi. So if your tonic is C and instead of going to D, you go to D-flat…well, even if you know nothing about music theory, your ear is instantly intweeged. If you want to paint Spanish Flamenco Dancer or Indian Snake-Charmer, or Some Kind of Vague Middle-Easternness, flat the 6 as well and you get this:

It’s called a Byzantine scale, one of several that appears in folk music throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Saint-Saëns sets up the climactic Bacchanale from Samson and Delilah by putting the Byzantine scale in a sinewy oboe. That scale is all you need to say “ooh, kinda biblical”:

0:24

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/TEhor3HeulE” parameters=”start=9 end=33″ /]

The Byzantine scale also appears in a place that is crazily incongruous and somehow brilliant — Dick Dale’s surf rock anthem “Misirlou.” The rapid-fire guitar, backbeat drums, and exotic scale made it the perfect heart-racing opening for Pulp Fiction. I’ve included the terribly upsetting profanity that precedes it because — well Tarantino, first of all, but also it’s part of the emotional crescendo that makes the song selection so spot-on:

1:40

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/oOoBomvuYnw” parameters=”start=20 end=56″ /]

God I love the cool, sinister energy of that song. (Dick Dale’s complete “Misirlou” is at the end of the post.)

As it turns out, Dick Dale wasn’t just borrowing the scale for his surf anthem. “Misirlou” is a remake of a vaguely Middle-Eastern traditional song, possible Egyptian or Turkish, first recorded in Greece in 1927. The whole melody finds its way into the Dick Dale version:

1:17

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/LW6qGy3RtwY” parameters=”start=19 end=86″ /]

As it further turns out, Dick Dale’s connection to the scale isn’t crazily random. Dale was of Lebanese descent on his father’s side and grew up playing the tarabaki drum and hearing music based on these scales, which he then incorporated into his surf music.

Here’s the tarabaki (aka doumbek) in the hands of a master:

0:29

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/FYlWrI9C-pI” parameters=”start=12 end=72″ /]

Grow up in Southern California with Byzantine scales in your ears and a tarabaki rhythm under your hands and you’ll create something like this:

2:15

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/-y3h9p_c5-M” /]

Dick Dale photo by Paul Townsend CC BY-SA 2.0

Follow Dale on Facebook:

3 Ways the ‘Office’ Theme IS Michael Scott

Michael Scott, the hapless regional manager in The Office, is one of the great characters in television. That mix of blustering confidence in his mouth and self-doubt in his eyes is a picture of striving lameness — a mediocrity who has somehow convinced circus management he’s a high-wire walker, then suddenly finds himself 50 feet above a pit of flaming tigers, naked, deciding whether to spend the surplus on a new copier or chairs.

Steve Carell captures this perfectly in the character of Michael Scott. The show’s theme manages to do the same in music, three ways in 30 seconds.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/uyIVAm9PVrI” /]

1. Dat accordion

First there’s the choice of instrument for the melody. When an accordion is going full tilt boogie, chords and all, it can be incredible. But a single, reedy, wheezy little solo accordion line is the essence of striving lameness, reaching for Van Gogh’s Starry Night and managing only a velvet Elvis. It is Michael Scott.

2. Dat clash

The second is less obvious but even more important. Here’s where the accordion enters in measure 5. Top line is the accordion; middle line is piano; bottom line is bass:

The chord progression is simple: G-Bm-Em-C, almost but not quite the four chords every pop song is made of. Here it is simplified to block chords:

Something weird happens in the second bar. See how the wheezy accordion in the top line hangs on a G from the previous bar? Now look at the harmony in the second bar — specifically the lowest note in the middle staff. It moves from G in the first measure to F# in the second, even as the accordion hangs on G up above. The harmony is right — it’s a B minor triad. But Accordion Michael Scott is oblivious to the fact that the harmony changed beneath him. Because of course he is.

If they had both hung on and changed at the same time, it might have been a pretty thing called a 6-5 suspension. Instead, for two full beats we get G and F# mashing against each other like Steve and Melissa at the 25th reunion.

I’ll isolate those two lines and draw them out with a good trumpet patch in the audio:

Audio:

Hear that clash in the second bar? It’s intentionally wrong. It’s hamfisted and lame. It’s Michael Scott. And it happens twice in eight bars.

3. Rock on

So what do you do if you’re Michael Scott and you’ve just done something hamfisted and lame, twice? You double down, cue the drummer, and rock on:

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/uyIVAm9PVrI” parameters=”start=15″ /]

THAT is the most Michael thing of all.

Follow on Facebook: